Chapter 46 Tropical Parasitic Infestations

Parasitic infestation of the biliary tract is a common cause of hepatobiliary disease in developing countries and in rural areas of developed countries. With the advent of international travel and immigration, clinicians in developed countries will encounter these conditions with increasing frequency. Ascariasis, hydatid liver disease, clonorchiasis, opisthorchiasis, and fascioliasis are the commonly encountered parasitic infestations of the biliary tract. They may present with cholestasis, obstructive jaundice, biliary colic, acute cholangitis, and, less commonly, pancreatitis. In developing countries biliary parasitosis often mimics biliary stone disease. Abdominal ultrasound facilitates diagnosis in most cases. Although medical therapy remains the mainstay of treatment, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopic sphincterotomy with bile duct clearance are essential when biliary adverse events do occur.1 In contrast to ascariasis and hydatid disease, in which the radiologic assessment usually proves suspect, the diagnosis of clonorchiasis, opisthorchiasis, and fascioliasis requires astute clinical suspicion in nonendemic areas.

Ascaris Lumbricoides

The roundworm Ascaris lumbricoides is the most common helminthic infestation throughout the world, infecting an estimated 1 billion people. Cases have been reported in nonendemic areas in both developing and developed countries.2–5 The infestation is usually asymptomatic. A. lumbricoides organisms normally reside in the jejunum but are actively motile and can invade the papilla, thus migrating into the bile duct and causing biliary obstruction with a variety of hepatobiliary adverse events, including biliary colic, pancreatitis, and cholecystitis. Ascariasis has also been reported as the cause of postcholecystectomy syndrome.6 Identification of parasite DNA in biliary stones suggests that Clonorchis sinensis and A. lumbricoides may also be related to biliary stone formation.

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Biliary-pancreatic ascariasis is commonly reported in high endemic regions such as the Kashmir valley in India. In a study of 500 patients with hepatobiliary and pancreatic ascariasis, Khuroo et al. reported biliary colic in 56%, acute cholangitis in 24%, acute cholecystitis in 13%, acute pancreatitis in 6%, and hepatic abscess in fewer than 1%.7 Biliary-pancreatic ascariasis must be suspected in patients from an endemic area presenting with biliary symptoms.7 In this setting, identification of eggs, larvae, or the adult worm from bile or feces is strongly suggestive of the disease. Diagnosis is confirmed by ultrasound or ERCP. Abdominal ultrasonographic features highly suggestive of biliary ascariasis include the presence of long, linear, parallel echogenic structures without acoustic shadowing and the “four lines sign” of nonshadowing echogenic strips with a central anechoic tube representing the digestive tract of the parasite.8

ERCP and Endotherapy for Hepatobiliary Ascariasis

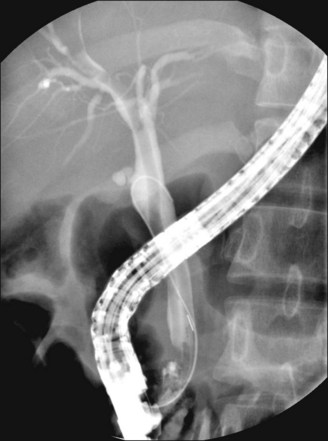

During endoscopy, worms can be seen in the duodenum and are often seen protruding from the ampulla of Vater. During ERCP, cholangiographic features of the Ascaris worm include the presence of long, smooth, linear filling defects with tapering ends (Fig. 46.1); smooth, parallel filling defects; curves and loops crossing the hepatic ducts transversely; and dilation of bile ducts (usually the common bile duct). With the recent availability of the SpyGlass direct visualization system (Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass.), the worm can also be visualized directly within the bile duct.

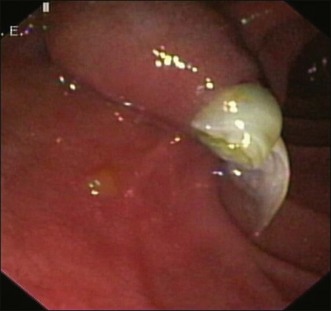

Endoscopy is the mainstay of treatment for biliary ascariasis.1,9–12 Worm extraction is easy when the worm protrudes from the ampulla of Vater (Fig. 46.2). The worm can be held with a grasping forceps and slowly brought out by withdrawing the endoscope from the patient. A Dormia basket can also be used, with the outer end of the worm maneuvered into the strings of the basket and gently held before extraction.10 It is best to avoid using a polypectomy snare for a protruding worm, as it tends to cut the worm. Remnant worms can lead to stone formation and all efforts must be made to ensure complete removal.1

Worms within the common bile duct occasionally protrude from the papilla after contrast injection. Alternatively, they can be extracted using a Dormia basket or a biliary occlusion balloon.1 It has been postulated that endoscopic sphincterotomy should be avoided in endemic areas in view of the high reinfestation rates and easy entry of worms into postsphincterotomy bile ducts. In a study including more than 300 patients, Sandouk et al. suggested that pancreatobiliary ascariasis was more common in patients with prior cholecystectomy or sphincterotomy.12 On the other hand, Alam et al. needed a wide sphincterotomy in 94.8% of the 77 patients with pancreatobiliary ascariasis in their study but did not report any major adverse events or recurrence after sphincterotomy in their cohort of patients.13 Similarly, Bektas et al. did not report any recurrence of biliary ascariasis in their patients after a papillotomy.14 Ascariasis may coexist with biliary calculi or strictures. In these situations, endoscopic balloon dilation of the biliary sphincter (sphincteroplasty) is an alternative to sphincterotomy to retrieve the parasite and associated calculi.15

In endemic areas pregnant women are prone to develop biliary ascariasis. Endoscopic intervention in such cases requires special precautions including lead shielding of the fetus and limitation of total fluoroscopic exposure. Failure of endoscopic extraction may require surgical extraction, which has increased risks of fetus death or premature labor.16

Extraction of the culprit worm is usually associated with rapid symptom relief and is successful in more than 80% of patients.10,12,17 However, infection may be associated with calculi or strictures, which can usually be dealt with endoscopically.9 Following endoscopic therapy, all patients should receive antihelminthic therapy to eradicate remaining worms. A single dose of albendazole (400 mg) is highly effective against ascariasis.18 In endemic areas, periodic deworming may have a significant role in preventing recurrences.

Echinococcus Granulosus

The “domestic strain” of Echinococcus granulosus is the main cause of human hydatid disease. Infections are found worldwide and remain endemic in sheep-raising areas. The life cycle involves two hosts; the adult tapeworm is usually found in dogs (definitive host) whereas sheep (intermediate host) are the usual host for the larval stages. Human exposure is via the fecal-oral route with food or water contaminated by the feces of the infected definitive host, usually dogs.19 Embryonated eggs hatch in the small intestines and liberate oncospheres that migrate to distant sites. The right lobe of the liver is the most common site for hydatid cyst formation. The majority of patients remain asymptomatic. In symptomatic patients, abdominal ultrasound and serologic studies usually establish the diagnosis.

In approximately one fourth of cases, hydatid cysts rupture into the biliary tree causing obstructive jaundice.20 Contents of the cyst (the scolices and daughter cysts) draining into the biliary ducts cause intermittent or complete obstruction of the bile duct, resulting in obstructive jaundice, cholangitis, and sometimes cholangiolitic abscesses. Rarely, acute pancreatitis complicates intrabiliary rupture of the hydatid cyst.21

Cystobiliary communication is common, occurring in 10% to 42% of patients.22,23 Cystobiliary communications are often recognized at surgery when cysts are stained with bile. Unrecognized cystobiliary communications may present in the postoperative period as a persistent biliary fistula, resulting in prolonged hospitalization and increased morbidity.

A hydatid cyst involving the pancreatic head has been rarely reported.24 These cysts enlarge, manifesting as acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, or obstructive jaundice, and are easily confused with pancreatic pseudocyst, tumor, or other congenital pancreatic cyst. Surgical intervention is generally required for management.

Endotherapy

Treatment of hydatid disease involves antihelminthic therapy (albendazole) combined with surgical resection of the cyst. Endoscopic intervention plays an important role (1) when intrabiliary rupture of the hydatid cyst occurs25,26 and (2) in the management of biliary adverse events following surgery.17,27–38

Intrabiliary Rupture of a Hydatid Cyst

Intrabiliary rupture is a common and serious adverse event of a hepatic hydatid cyst. The incidence varies from 1% to 25%39 and is usually because of higher pressure in the cyst, often up to 80 cm H2O.20 In a series of 16 patients, Bektas et al. found biliary rupture of the cyst in 8 patients.14 ERCP is indicated when intrabiliary rupture is suspected clinically (because of jaundice), biochemically (because of cholestasis), or sonographically (a dilated biliary ductal system in association with hydatid cysts in the liver).17,27,28 Duodenoscopy sometimes shows whitish, glistening membranes lying in the duodenum or protruding from the papilla of Vater. On cholangiography, the hydatid cyst remnants appear as (1) filiform, (2) linear wavy material in the common bile duct representing the laminated hydatid membranes, (3) round or oval lucent filling defects representing daughter cysts floating in the common bile duct,38 or (4) brown, thick, amorphous debris.28 Cholangiography often reveals minor communications, particularly in peripheral ducts, which are of unclear clinical significance.

In patients presenting with obstructive jaundice or cholangitis, endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy facilitates extraction of the cysts and membranes using a Dormia basket (Fig. 46.3) or a biliary occlusion balloon.30,31 Saline irrigation of the bile duct may be necessary to flush out the hydatid sand and small daughter cysts. Life-threatening episodes of acute cholangitis can be managed by initial nasobiliary drainage as a temporizing method, followed by extraction of hydatid cysts and membranes with or without sphincterotomy. The nasobiliary drain output can be examined for hydatid hooklets or membranes. Endoscopic management of acute biliary adverse events allows for definitive surgery to be performed electively. Rarely, rupture with complete drainage may be treated endoscopically alone.40

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree