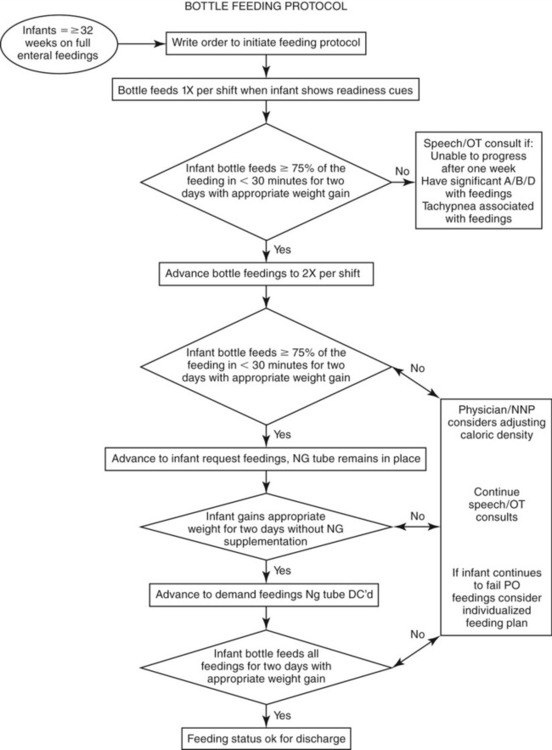

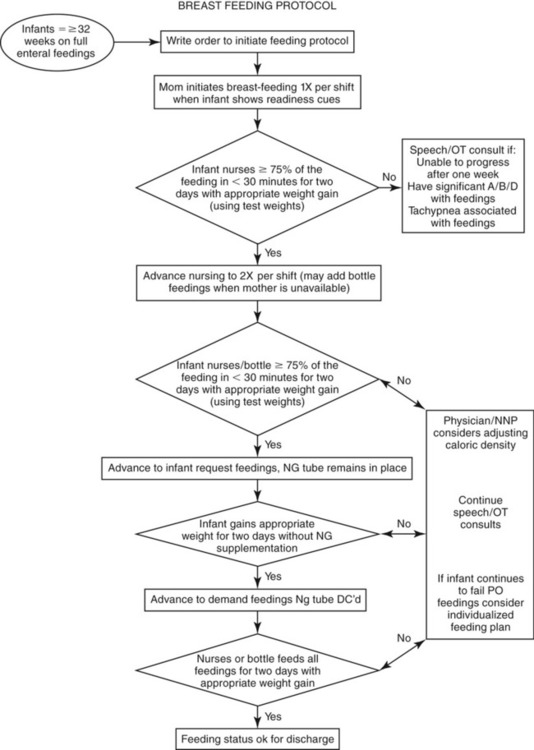

1. Identify and understand why a premature infant needs positional boundaries. 2. Understand the potential benefits of skin-to-skin care. 3. Identify the cues indicating when an infant might be ready to eat. 4. Understand the benefits of using a pacifier for the premature infant. 5. Discuss the formulation of child- and family-oriented goals for feeding therapy. 6. Describe prefeeding therapy strategies for the child with oral motor dysfunction. 7. Describe prefeeding therapy strategies for the child with a sensory-based feeding disorder. 8. Describe a potential sequence of activities for feeding therapy sessions. The key to developmental approaches to treatment of swallowing disorders in infants is to foster the neurodevelopmental skills that will lead the infant from a state of mature sucking to a state of mature feeding. Coordinated oral feeding is difficult work for most premature, sensory and motorically disorganized, structurally impaired, and medically fragile infants. Swallowing management of infants usually requires individualized treatment planning and approaches. This approach depends on the infant’s physiologic stability, alertness levels, neural organization, and available levels of energy (see Chapter 4). Infants need to be able to maintain physiologic, motor, sensory, and state stability to have pleasurable and successful feeding. The combined goals of the feeding specialist and parents for management and treatment usually include improving the infant’s overall stability with integrated developmental care, proper positioning in an incubator or crib, proper positioning during feeding, use of appropriate latching skills and positioning for breastfeeding, and use of appropriate bottles and nipples. The entire process should be positive for the infant and caregiver with minimal stress and maximal social enjoyment. Infant development is a process that involves an individual’s ability to integrate new demands and new information, achieving stability at each new developmental level (see Table 4-2). The goal of facilitating the development of feeding skills in the neonatal intensive care unit should be directed toward assisting the infant in achieving stability at each level and should be viewed as important steps leading to a more complex process such as oral ingestion.1 Developmentally supportive care promotes the importance of compassionate touch, cluster care (see Chapter 1), proper positioning during feeding and nonfeeding activities, and controlling environmental stimuli such as excessive noise and light.2 Developmental supportive care also should assist the infant in maintaining organization that will help the infant in attaining safe and positive feedings throughout the day. The key to successful feedings is to recognize the infant’s cues that may disrupt his or her stability and to minimize negative experiences during feeding. Skin-to-skin (also known as “kangaroo care”) is contact between an infant and parent that usually is chest to chest with the infant in an upright and prone position. The infant’s arms and legs are flexed close to the baby’s body with the hands near the mouth. Usually a blanket is wrapped around both the parent and infant (Figure 13-1). Skin-to-skin posturing ideally should last 60 to 90 minutes or as long as the infant remains stable. Skin-to-skin usually is started at the completion of a feeding or during gavage feeding. The environment should be quiet with the lights dimmed throughout the session. Skin-to-skin care can be done with the most medically fragile infant, even one who is supported by mechanical ventilation. Skin-to-skin care is a beneficial developmental intervention for the infant and the parent. Skin-to-skin touch benefits the infant by stabilizing physiologic parameters such as heart and respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and oxygen consumption. It also encourages sleep, a higher mean daily weight gain, and breastfeeding success as well as fosters neurobehavioral development.3–5 It provides a direct benefit to the caregiver because bonding often produces relaxation, which in turn decreases the stress associated with hospitalization. Skin-to-skin contact allows parents and their infant to learn each other’s smells, scents, and voices. For some mothers it increases breast milk production and prolongs the duration of breastfeeding.6 Research has demonstrated that children at a very young age often bond when positioned together, as in the case of multiple births. It has been demonstrated that co-bedding of multiples of infants may encourage self-regulation, thermoregulation, respiratory regulation, and improved growth.7–9 When this circumstance is possible, it is helpful to have an incubator with dual temperature probe capability, adequate-sized open cribs, and a receiving blanket large enough to swaddle more that one child to assist in co-regulation (Figure 13-2). Considerations with co-bedding include whether the physical environment can support dual monitoring, the size of the support staff, the size of the blankets and incubators, and the need for infant support lines such as those to support nutrition and respiration. If co-bedding involves twins, there should be maintenance of identification to track changes in each infant’s developmental skills. Pacifiers are commonly used with preterm infants to assist in the nonnutritive sucking process. Pacifiers also may assist in strengthening the suck and in providing a more rhythmic suck pattern. Pacifiers come in various shapes, lengths, and sizes. The size should match the size of the infant’s oral cavity, sensitivity, gag response, and sucking needs (Figure 13-3). Pacifiers may help calm the infant during stressful situations and provide positive oral stimulation during gavage feedings.10 Bottles are made of hard or soft plastic. Softer plastics are flexible and can be squeezed to assist in the rate of flow (Figure 13-4). Softer bottles are commonly used in children with cleft palate (see Chapter 4). Ideally, bottles should be clear so that the fluid inside is visible. Nipples (or teats) are characterized by the material composition that determines the nipple’s shape, size, and flow rate. A variety of nipples are available for term and preterm infants (Figure 13-5). Some nipples are made of silicone that is clear, firm, and less likely to collapse. A plastic nipple may be tan colored and will collapse easily under pressure. The shape of the nipple is either straight or orthodontic. The straight nipple requires more tongue cupping by the infant and more pressure before it will collapse. It also provides a consistent flow rate, although it may make it more difficult for the infant to draw the tongue posteriorly to the pharynx. An orthodontic nipple is useful when the infant has a flatter and larger tongue, requires less pressure to collapse, has a less predictable flow rate, and can draw the infant’s tongue back to the pharynx. Similar to pacifiers, the size of the nipple should match the size of the infant’s oral cavity. Standard and small sizes are available for premature infants. One rule of thumb for nipple choice is that if the infant is able to suck on your finger, he or she usually will tolerate the standard-size nipple. There are many varieties of flow rates for nipples. Flow rates need to be adjusted as the infant matures. The flow rate usually depends on the infant’s sucking strength and the viscosity of the fluid. For instance, breast milk has a higher flow rate than formula. Nipples for premature infants generally tend to flow more quickly. Variable-flow–rate nipples should be used with caution because the slowest rates with this type of nipple are generally faster than most fast-flow straight nipples. Selecting the correct nipple for a premature infant is similar to the process of selection for a term infant. Flow rate adjustments are made by assessing the maturity of the suck, the coordination of the swallow, breath, burst control, and the overall respiratory status of the infant before and during feeding. Determining the readiness for advancement in oral feeding is an individualized approach. If the infant is older than 34 weeks’ gestational age, the feeding specialist will initiate cue-based feedings, allowing the cues from the infant to drive the schedule (see the section on readiness to eat above). Infants may be able to feed before 34 weeks if cueing, ready, and able to maintain some physiologic stability. Typically infants start with one feeding per 12-hour shift and advance as the infant tolerates the schedule. Two evidence-based approaches using a cue-based program for oral feeding by bottle or breast are presented in Figures 13-6 and 13-7. The SOS approach uses systematic desensitization to help a child build new skills. This includes the implementation of the “Steps to Eating,” which includes substeps of tolerating the presence of food, interacting with food, the ability to smell food, touching food, tasting food and, finally, eating. This approach has been used with individuals and in group treatment settings. Studies of group programs have shown gains in both weight and height and a 41% increase in expanding food variety.11,12 Children develop many feeding behaviors as a result of negative experiences surrounding food and feeding related to medical complications. However, once the medical problem is under control or is resolved, the child is left with learned experience and behaviors, often as a protective response that may interfere with normal feeding. The child may establish a strong avoidance pattern that continues between the child and the caregiver whenever food is presented. Treatment should include behavioral principles that reward positive behaviors and decrease negative behaviors.13 Behavioral feeding programs have been developed by several centers and specific practitioners. Behavioral feeding programs have been successful for up to 67% of children with feeding disorders stemming from a variety of causes.14 The goal of a structured behavioral feeding program is to increase acceptance of oral intake through behavioral reinforcement strategies. Aversive behaviors that should be addressed include food stuffing or holding, spitting food out, food selectivity or refusal, tantrums or crying, refusal of the high chair, blocking, grimacing, and intentional vomiting or gagging. The Structured Behavioral Feeding Program, established by Krisi Brackett, was developed to address these areas.13 The program fully integrates all the child’s medical and therapeutic background and needs with a behavioral intervention plan. The program begins with appropriate supportive positioning. Progressive applications of spoon placement are used with a prescriptive approach to what may be on the spoon (often using a dry spoon) and a specified number of trials. Rewards are used consistently throughout the program. Rewards may include a short turn with a toy (lasting less than a minute), praise, a few seconds of music, or the reading of a portion of a page in a favorite book. At first, rewards may be given each time the child accepts the spoon, gradually reducing the number as acceptance increases. Acceptance of the spoon could be paired with the child being allowed to play with a toy. The toy is then put away and the child is again offered the spoon. This sequence is repeated until the child accepts the spoon 10 times. The Structured Behavioral Feeding Program progresses through a series of structured steps with practice sessions two to four times per day. As the child progresses, the feeding specialist moves toward increasing food variety and volume.15 Many individuals with impaired oral motor skills are not able to follow a command for oral movement. To better serve these individuals, Debra Beckman developed specific interventions that provide assisted movement to activate muscle contraction and to provide movement against resistance to build strength. The focus of these interventions is to increase functional response to pressure and movement, range, strength, and variety and control of movement for the lips, cheeks, jaw and tongue. The interventions needed are determined by using the Beckman Oral Motor Protocol.15 The protocol uses assisted movement and stretch reflexes to quantify response to pressure and movement, range, strength, variety and control of movement for the lips cheeks, jaw, tongue, and soft palate. The assessment is based on clinically defined functional parameters of minimal competence and does not require cognitive participation. Because these components of movement are functional and not age specific, the protocol is useful with a wide range of ages (birth to geriatric) and diagnostic categories. Oral motor skills affect basic survival such as sucking and swallowing by infants. These skills begin by the third month of gestation. Development of these skills enhances the progression from breast milk or formula, then to pureed foods and to table foods, as well as the skills needed to progress from sucking a nipple, to using a wide variety of utensils, including straws, cups, spoons, and forks. These areas of performance are scored with three trials in each area of motor performance based on movement consistency. Although there are no published norms for performance, the test is used to document individual progress in specific areas, including improved oral motor function. Beckman recommends that a primary therapist be designated (typically a licensed SLP) to assess the oral motor skills, plan the oral motor interventions needed, and work closely with other team members. Families come to the feeding therapy setting with many different experiences derived from culture, education, personal experiences with food and eating, family pressure, and the experiences and expectations that they have already had with their child. The family of a child with a feeding disorder experiences emotional and other psychological stressors on a daily basis. Parents blame themselves for their child’s poor eating, even in the presence of a known physical problem over which they have no control. For the parent of an infant, their sense of “success” is directly tied to the child’s feeding skills and weight gain.16,17 Parents of children of all ages often blame themselves for their child’s poor feeding. Some consequences of these “failures” include depression, anxiety, anger, and frustration. It is important that the feeding specialist refer the family to a qualified psychologist if any of these problems are observed or reported. It is not uncommon that families arrive at the clinical feeding evaluation and subsequent treatment sessions with a certain degree of stress. An important component of evaluation and treatment involves working with that stress through appropriate levels of information provided to the families and identification of areas in which the child and family are showing progress. High stress levels contribute to negative parent-child interactions, especially within the feeding environment. It is crucial for health care providers to help parents identify specific stressors and develop coping strategies to deal with these stressors as effectively as possible. Decreases in stress are noted when the families realize their goals are being met, their perceptions of their child’s eating problems are validated, and specific feeding or medical problems are clarified.17 Integration of the caregiver in feeding therapy plays a critical role in intervention. Effective management of feeding disorders should always be seen as a partnership between the caregiver and the interdisciplinary feeding team. The additional gain is an increased feeling of competency by the caregiver who is appropriately trained in feeding the child with special needs. Providing caregivers with appropriate feeding training, setting of realistic goals, regular instruction for home practice, and the expectation for periodic setbacks can help the child and the caregiver achieve the greatest benefit from feeding therapy.18 Assisting the family with the importance of objective documentation of feeding activity using a food diary (see Appendix 13-A) can facilitate the communication between the feeding specialist and the family in discussions of how therapy is progressing. The completion of a food diary provides information on the type and quantity of food consumed, the timing of tube and oral feedings, and the adequacy of hydration. The feeding specialist should instruct the family to keep a detailed record for three consecutive days. This information allows the feeding specialist to determine whether a dietary consultation is necessary.

Treatment for Infants and Children

FOSTERING STABILITY AND ORGANIZATION

Developmental Supportive Care

Skin-to-Skin Care

Co-bedding

PACIFIERS, BOTTLES, AND NIPPLES

CUE-BASED FEEDING SCHEDULE

THEORIES OF FEEDING TREATMENT

Sequential Oral Sensory Approach

Structured Behavioral Feeding Approach

Beckman Oral Motor Approach

FAMILY-FRIENDLY GOALS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree