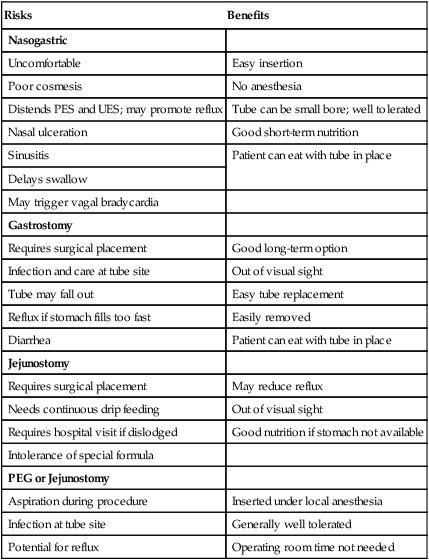

1. Present the basic principles of medical ethics as they relate to the swallowing-impaired patient. 2. Discuss the risks and benefits of alternative types of feeding. 3. Highlight the differences between factors that predict aspiration and those that predict aspiration pneumonia. 4. Present an approach for weaning from feeding tubes. 5. Present examples of ethical dilemmas resulting from the placement or retention of alternative forms of feeding. The Patient Self-Determination Act took effect on December 1, 1991. The act established guidelines to allow patients to participate fully in decisions regarding their health care, particularly decisions made in circumstances of severe or terminal illness. The act strives to establish a patient-physician interaction that allows both parties to balance individual morals and values against the known risks and benefits of proposed medical care. For example, patients might want to decide under which circumstances they would want to be resuscitated or whether they would want to be nourished by a feeding tube to sustain life. Counseling patients, families, and caregivers on the risks and benefits of tube feeding may involve the expertise of the dysphagia specialist.1 One study found that speech-language pathologists (SLPs) who manage patients with dementia are involved in the decision making in 65% of cases when the recommendation is made for some type of alternative nutrition.2 The gastrostomy tube is placed directly into the stomach with the assumption that the digestive processes of the stomach are intact. Formula is passed through a catheter that sits on the outside of the stomach. If the stomach is not functioning, the feeding tube may need to be placed into the jejunum of the small intestine. Because the stomach is bypassed, specialized, predigested formulas are required for jejunal tube feedings. Some clinicians argue that jejunal placement reduces the risk of reflux of the tube-fed material into the pharynx because the pyloric valve provides an additional barrier to retropulsion of stomach contents into the esophagus. However, the experimental evidence does not clearly support this contention.3 Table 15-1 summarizes the medical risks and benefits of enteral tube feeding. TABLE 15-1 Medical Risks and Benefits Associated with Enteral Tube Feeding PES, Pharyngoesophageal segment; UES, upper esophageal sphincter. Parenteral nutrition is indicated when the gastrointestinal tract cannot be used because of medical complications such as gastroparesis, obstruction, or bleeding. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is a specialized formula that most commonly is delivered into a central vein (subclavian or internal jugular). Although there are potential medical complications from this therapy, such as pneumothorax, patients can be supported nutritionally with this formula for 4 to 6 weeks if necessary.4 Peripheral parenteral nutrition (PPN) is a form of nutritional support delivered through a peripheral vein. Because of potential medical complications, this therapy can be used effectively for only 7 to 10 days.4 Intravenous feeding is a common form of parenteral nutrition, usually providing hydration and medication only rather than more complex elements such as amino acids. Hypodermal clysis is a form of parenteral nutrition that is given for hydration through the subcutaneous tissues in the chest, thigh, or abdomen. Table 15-2 summarizes parenteral and enteral alternative nutrition and hydration. TABLE 15-2 Summary of Potential Methods of Providing Nutrition

Ethical Considerations

MEDICAL ETHICS

TUBE FEEDING

Enteral Nutrition

Gastrostomy and Jejunostomy Tubes

Risks

Benefits

Nasogastric

Uncomfortable

Easy insertion

Poor cosmesis

No anesthesia

Distends PES and UES; may promote reflux

Tube can be small bore; well tolerated

Nasal ulceration

Good short-term nutrition

Sinusitis

Patient can eat with tube in place

Delays swallow

May trigger vagal bradycardia

Gastrostomy

Requires surgical placement

Good long-term option

Infection and care at tube site

Out of visual sight

Tube may fall out

Easy tube replacement

Reflux if stomach fills too fast

Easily removed

Diarrhea

Patient can eat with tube in place

Jejunostomy

Requires surgical placement

May reduce reflux

Needs continuous drip feeding

Out of visual sight

Requires hospital visit if dislodged

Good nutrition if stomach not available

Intolerance of special formula

PEG or Jejunostomy

Aspiration during procedure

Inserted under local anesthesia

Infection at tube site

Generally well tolerated

Potential for reflux

Operating room time not needed

Parenteral Nutrition

Type of Nutrition Delivery

Route of Delivery

Method of Delivery

Indications for Use

Types of Formula

Possible Complications

Simple IV/CTPN

IV (small vein; catheter inserted or surgically placed for CTPN in deep central vein)

Continuous or cyclic infusion by pump

Supplemental hydration; restoration of fluid and electrolyte balance, need for complete parenteral nutrition or long-term CTPN

Nasogastric tube

Catheter/tube placed transnasally to the stomach

Intermittent or continuous drip by pump

Short-term alternative to oral intake (approximately 2 weeks); transnasal insertion, easily removed

Commercial nutritionally complete (standard, hydrolyzed, modular) supplements; regular liquids

Misplacement into the airway; irritation to nasal, pharyngeal, esophageal mucosa; discomfort; negative cosmesis; may affect swallow function; may contribute to reflux and aspiration

G-tube/PEG

Feeding tube inserted directly into the stomach

Bolus or gravity (syringe); drip by infusion pump

Option for long-term alternative to oral intake; does not necessarily preclude oral intake in certain cases

Commercially prepared nutritionally complete enteral formulas; fiber supplements, supplemental and regular liquids, select medications; some individuals may liquefy table foods

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, reflux, clogged tube, skin irritation at gastrostomy site; aspiration

J-tube/PEG

Feeding tube inserted directly into the jejunum (small intestine)

Bolus or gravity syringe; drip by infusion pump

Does not require stomach for digestion; allows enteral nutrition earlier after stress or trauma; less risk of reflux and aspiration

Commercial prepared nutritionally complete enteral formulas; fiber supplements, supplemental liquids

Loss of controlled emptying of the stomach; misplacement; diarrhea, dehydration

Hypodermal clysis

Subcutaneous; common infusion sites are the chest, abdomen, thighs, and upper arms

Injection (3 L in 24 hours/two sites)

Hydration supplement for mild to moderate dehydration

Saline; half saline/glucose; potassium chloride can be added

Mild subcutaneous edema ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ethical Considerations