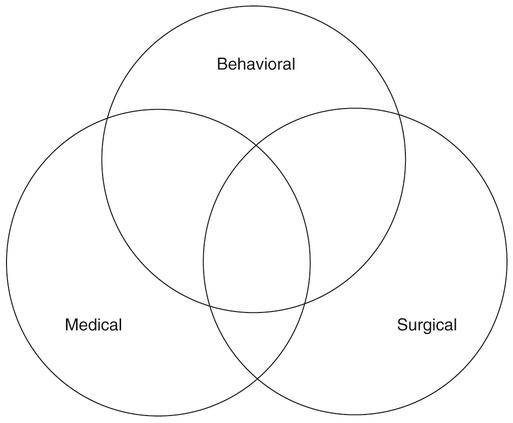

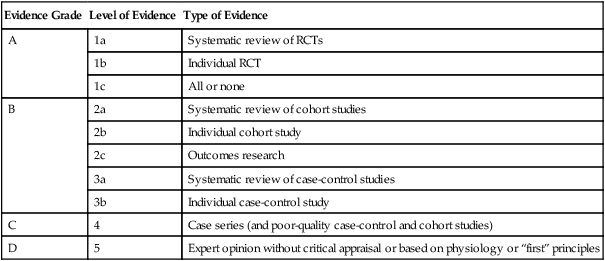

1. Introduce the concept of how evidence-based practice guides treatment decisions. 2. Discuss general factors that influence therapy decisions. 3. Provide examples from the three major classes of therapeutic interventions for dysphagia. 4. Discuss how the evaluation results will affect treatment planning. 5. Present a decision tree for selecting and implementing dysphagia therapy. In all fields of health care, clinicians have been challenged to evaluate and use available research evidence to solve clinical problems and provide the best patient care possible in the most cost-efficient manner. Examples of how EBP affects patient care are numerous. For example, assume that a clinician had been using the tactile-thermal stimulation technique (see Chapter 14) with patients who show swallowing onset delay because of experimental evidence suggesting its application with that particular group of patients. However, when reviewing additional evidence in multiple studies with similar patients, the investigators reported that the effect was minimal. In this circumstance the clinician might be hesitant to apply the treatment. However, before changing practice, the clinician must evaluate the strength (believability) of the new evidence before he or she alters the treatment approach. Even in the face of strong evidence, some clinicians find it hard to abandon their own experience and intuition. Complete reliance on experimental evidence runs the risk of setting patient care guidelines and paths of care that experience suggests may not be in the patient’s best interest. The intersections of experimental evidence, clinical experience, and patient desires ultimately lead to the best treatment approach. When using an EBP model it is incumbent on the clinician to consult the research literature to evaluate treatment effectiveness or efficacy in patients similar to the one requiring evaluation or treatment. Assuming the clinician wants to review the evidence pertaining to a clinical question, the next step would be to consult relevant databases using key search terms that might help answer those questions. Terms such as “posture,” “swallowing,” “outcomes,” and “treatment” might be used in the initial search. Finding the relevant evidence can be accomplished by using databases such as MEDLINE or PubMed, or Web sites that summarize data such as the Cochrane Library or the American College of Physicians. Typing terms in a Web search such as “evidence based” and “clinical trials” can lead to other relevant databases. Government-based Web sites such as www.guideline.gov (National Guideline Clearinghouse) can be a useful starting point in an evidence-based search. If the search is directed toward a specific disease such as Parkinson’s, accessing a specific organization’s official Web site also is a valuable point of departure. Because the study’s design often determines the relative strength of the evidence, it is important to know what constitutes weak evidence for any given outcome and what constitutes stronger evidence for the same outcome. Table 12-1 presents a classification system for grading levels of evidence according to the study’s design characteristics. For instance, the highest level of evidence (grade A or 1) is associated with study designs that are randomized, controlled trials (RCTs). A lower grade (grade D or 5) is associated with studies that report on a series of patients. Investigators who use the RCT design to study a question are bound by much stricter criteria to answer their question. In general, these criteria try to eliminate any bias in the study that might shed doubt on the believability of the results. Some of these criteria include a large sample size in an experimental and control group with subjects assigned randomly, measurements made by investigators who are blinded to the study, and accounting for the outcomes of all study subjects at the end of the experiment. Study designs at levels B, C, and D may meet some of these criteria, but not all of them. The fewer criteria met, the weaker the evidence. In general, a clinician would have more confidence in studies graded at grade A than at grade D. Therefore the applicability of the findings from RCTs would be applied clinically with more confidence than findings from studies that reported on similar outcomes with a case series design. Such criteria can help the clinician decide which diagnostic or treatment approach might fit the patient and how much confidence to place in the outcome. An extensive discussion of each level of evidence and its corresponding characteristics is beyond the scope of this chapter. Readers are referred to The Handbook of Evidence-Based Practice in Communication Disorders for a thorough discussion.1 TABLE 12-1 Classification System for Grading Levels of Evidence RCT, Randomized controlled trial. Adapted from Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, 2001. Judgment of the strength of the experimental evidence must be complemented by other analytic methods. For example, were the relevant studies done with patients similar to the patient in question, or were the characteristics in the reference sample different—such as age or gender? Was the treatment protocol in the study described precisely enough so that it could be replicated? Do you have the skills needed to replicate the treatment? For example, if the treatment described the use of certain equipment, do you have the equipment and are you trained to use it? And, finally, are the outcomes in the study similar to the ones you and your patient envision? Even the best-designed, grade 1 study may not be applicable to your clinical question. One also must judge whether the study under scrutiny has clinical significance. That is, if the conclusion from a study was that technique “X” improved hyoid elevation by 2 mm in a group of acute poststroke patients, is that change clinically significant or was it only a statistically significant difference? In this example, unless the study reported that a 2-mm change in hyoid elevation actually made a difference in airway protection or in an improvement of dietary intake, one may choose to ignore the data even though statistically technique “X” made a difference. Chapter 14 provides a more detailed discussion of study designs as they relate to answering clinical questions. Beyond specific goals of treatment, clinicians must consider the nature of the swallowing deficit and the treatment options available to them and the patient (NOTE: these are not always the same). Box 12-1 summarizes some issues that might be addressed regarding the swallowing deficit. A basic question might revolve around feeding versus swallowing processes: Are there physical or cognitive factors that preclude successful feeding but that do not interfere with swallowing function? Are both of these factors present and, if so, do they interact in a positive or negative manner? Certain dysphagia-causing diseases might demonstrate differences between voluntary or involuntary motor processes. If differences are present, are there swallowing activities that may be used to tap into voluntary versus involuntary motor processes? Stage of deficit is an artificial delineation often used for convenience. Are the swallowing deficits primarily located within the oral, oropharyngeal, pharyngeal, or esophageal component? Clinicians must also remember that not only are these “stages” artificial, but that the swallowing mechanism is interactive—events occurring in one anatomic area have the potential to affect performance in another area (see Chapter 2). A difficult clinical task can be attempting to separate the specific swallowing deficit from any compensatory activities used by individual patients. For example, consider the patient who attempts to swallow but immediately begins to expectorate, or a patient who demonstrates a pattern of multiple, incomplete swallows interspersed with throat clearing, resulting in only a minute amount of material actually swallowed. Does this pattern reflect a specific pattern of impaired physiology? Does it reflect the presence of compensations intended to protect the airway, or are there other possibilities? In some cases, this distinction may not be important. However, in others, it may be important to understand what might be changed as a result of therapy versus what might not be changed. This consideration may affect the decision to engage in therapy and, if so, the direction of therapy. Another noteworthy point is that dysphagia treatment is rarely unifocal. Dysphagia is the result of underlying disease or disorder processes. Consequently, patients with dysphagia often receive therapies from medical, surgical, and/or behavioral realms. Clinicians who are treating patients with dysphagia should be aware of concomitant treatments, as well as dysphagia treatments in other realms that may either work together or in place of behavioral treatment strategies the SLP may provide. Figure 12-1 is a schematic reminder of how these therapy categories may interact. In certain clinical situations one category may comprise the primary or sole treatment approach. In other situations two or all three categories may interact to form the most beneficial intervention. Patients bring to any clinical situation a variety of unique circumstances. Box 12-2 provides a list of potential patient-related considerations that may have an impact on dysphagia treatment options and decisions. Because dysphagia is the result of underlying disease processes, the cause of dysphagia should be understood as best as clinically possible because the underlying disease presents a clinical course that has direct impact on swallowing function and benefits from various intervention strategies over time. The severity of dysphagia is a more complex concept than might first be imagined. How is the severity of dysphagia graded? Some clinicians and investigators have used impairment of swallowing physiology based on instrumental examination,2 whereas others have used more functional measures such as amount of food or liquid taken by mouth.3,4 Some clinicians may believe that patients who take no food by mouth also have the poorest swallowing physiology. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Patient status may change over time, and some patients who receive only nonoral feeding may actually have adequate swallowing physiology to ingest some food or liquid by mouth. Thus severity of dysphagia should not be considered a unitary concept because many factors are involved. The patient’s residential environment also can affect the nature of dysphagia interventions (see Chapter 1). The needs of the patient in the intensive care unit are different from those of the individual receiving outpatient therapy. In addition, the resources available in different environments differ dramatically. Clinicians working in academic medical centers often have more resources available than do clinicians working in rural long-term care facilities. Box 12-3 presents a list of considerations that apply in choosing any specific treatment technique. Clinicians must consider which treatment options are realistically available. In determining this, the following should be considered: the physical presence of technology/equipment required to use a specific technique (e.g., surface electromyography [sEMG] biofeedback), the clinician’s knowledge of and skill in performing a specific technique, and the patient’s acceptance of the technique. (Does the patient understand the instructions? Is he or she able to perform the technique? Can the patient afford the technique? What are the demands on the patient to adequately perform the technique?)

Treatment Considerations, Options, and Decisions

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVALUATING EVIDENCE

Evidence Grade

Level of Evidence

Type of Evidence

A

1a

Systematic review of RCTs

1b

Individual RCT

1c

All or none

B

2a

Systematic review of cohort studies

2b

Individual cohort study

2c

Outcomes research

3a

Systematic review of case-control studies

3b

Individual case-control study

C

4

Case series (and poor-quality case-control and cohort studies)

D

5

Expert opinion without critical appraisal or based on physiology or “first” principles

GENERAL TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

PATIENT-SPECIFIC TREATMENT

APPROACH-SPECIFIC TREATMENT

Treatment Choices

Treatment Considerations, Options, and Decisions