Chapter 70 TRANSVAGINAL REPAIR OF APICAL PROLAPSE: THE UTEROSACRAL VAULT SUSPENSION

For decades, the reconstructive treatment of uterine prolapse or post-hysterectomy vaginal cuff descent has included suspension of the vaginal apex. Reconstructive urologists and gynecologists have developed many techniques, including abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal routes of surgery, for the correction of apical descent.1 Our understanding about which technique or approach is superior with regard to efficacy, safety, and durability is limited by a relative lack of level I evidence. Although many well-designed, retrospective reports (each with a large study population and long-term follow-up) exist to give us useful information about particular procedures for the correction of vault descent,2–17 we are still unsure which procedure is best for any particular patient. The techniques used to treat pelvic organ prolapse are largely shaped by each surgeon’s experience and training and not necessarily influenced by prospective, outcomes-based research.

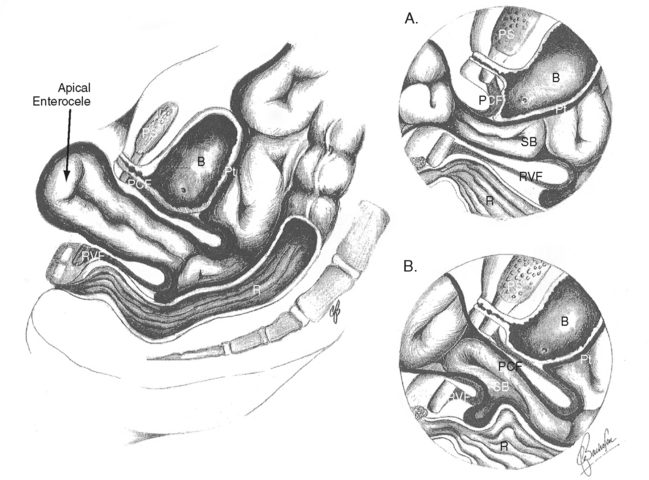

To compound the problem of sparse well-designed and executed, randomized surgical trials, we are also handicapped by confounding, coexisting pelvic support problems. It is difficult to study apical prolapse in isolation, because most patients present for treatment with many support defects (Fig. 70-1) and associated pelvic floor dysfunction (e.g., urinary incontinence, defecatory dysfunction, pelvic pain, difficulty with sexual intercourse). We are, for example, unsure of how our choice of treatment for cystocele or urethral hypermobility may affect the outcome of our vault suspension.

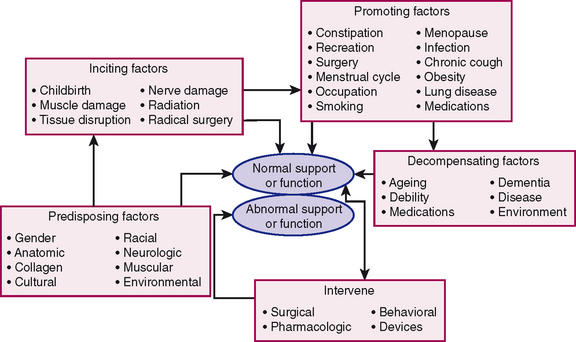

Operative technique in other fields is often driven by an understanding of the cause and natural history of the surgical problem, and this often helps guide surgical therapy. Unfortunately, we are still uncertain about these variables in pelvic organ prolapse. Bump and Norton18 have provided a useful model with which we can consider how prolapse develops and progresses (Fig. 70-2), but in their own words, the model is “based mainly on expert opinion and supported by limited epidemiologic and clinical evidence. None of the factors has been studied in a longitudinal fashion in a representative study.”

Figure 70-2 Model developed by Bump and Norton18 to propose a mechanism for the development and progression of pelvic floor dysfunction, including pelvic organ prolapse.

HISTORY

Written history of gynecologic surgery documents that uterosacral ligaments have been used in vaginal reconstructive surgery for at least the past century, but it is difficult to say who was the first person to conceive of the importance of these structures in supporting the uterus and vaginal apex. John Burns, a renowned Scottish anatomist and surgeon, was the first person to write about the importance of the uterosacral ligaments. In his 1839 book, The Principles of Midwifery including the Diseases of Women and Children, Burns19 wrote:

The first mention of the use of uterosacral ligaments to suspend the vaginal apex as treatment for prolapse was by the American gynecologist Norman F. Miller, who in 1927 described the placement of a “no. 2 chromic catgut suture on a small full curved needle passed through the peritoneum and underlying fascial and muscular structures at the base of the sacro-uterine ligament, approximately 1½ inches below the promontory of the sacrum.” Since this report, the use of the uterosacral ligament for apical prolapse has been described by other surgeons. McCall first described his transvaginal culdoplasty technique for treating enterocele with associated vault prolapse in 1957.20 Lee and Symmonds21 published what became known as the Mayo modification in 1972. As vaginal surgeons made developments in the treatment of apical prolapse with the uterosacral ligament (among other attachment sites, including the iliococcygeus fascia22 and the sacrospinous ligament23) throughout the 20th century, parallel progress was being made in the abdominal24,25 and laparoscopic26 approaches to vault prolapse. In the later half of the 20th century, less attention was attributed to a vaginal uterosacral vault suspension as other techniques and approaches became widely used with acceptable results.

Four prominent gynecologic surgeons—Cullen Richardson (1923-2001), William Saye, Tom Elkins (1950-1998), and Bob Shull—met in Atlanta in the fall of 1992 to review videos of laparoscopic support procedures and discuss surgical strategies for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse (interview with B. Shull, 2005). Richardson had previously stressed the importance of finding specific fascial defects and repairing them to achieve optimal restoration of pelvic anatomy.27 After working together, Richardson and Saye developed what is now known as the Richardson-Saye laparoscopic technique of enterocele repair and vault suspension, which applies the principles of site-specific repair26 to the laparoscopic approach. During their meeting in 1992, it occurred to the assembled group that they could find specific fascial defects, repair them, and resuspend the newly reconstructed vault to the uterosacral ligaments from a vaginal approach. In 2000, Shull and colleagues6 published their technique and experience with this approach in 302 consecutive women. With only minor modifications, this is the surgical technique that we now use for the transvaginal correction of apical prolapse, and it is this procedure that we describe in this chapter.

TECHNICAL ASPECTS OF THE UTEROSACRAL LIGAMENT VAULT SUSPENSION

We are inclined to offer transvaginal repair to most of our patients. In our hands, this route of surgery has been safe, efficacious, and durable.3 We have developed a bias, however, in that we prefer the abdominal sacral colpopexy to treat apical prolapse in our younger and more physically active patients. We are also likely to consider abdominal sacral colpopexy in patients with complete vaginal vault inversion.

Preoperatively, we discuss with the patient the reported incidence of complications associated with such major surgery in general and with this technique in particular. The ureteral obstruction rate is between 0% and 11%.2,4–6 Intraoperative or postoperative blood transfusion may be required in up to 1% of patients.2,4–6 It is important that the patient have realistic expectations of what can be achieved and that recurrent prolapse of the vault or the development of other vaginal defects is not uncommon. Interference with sexual function, in particular loss of vaginal depth and caliber, is not uncommon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree