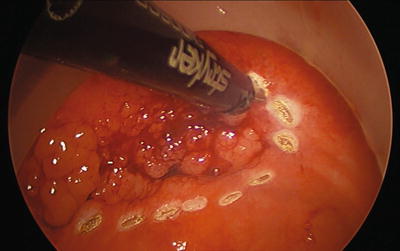

Fig. 25.1

The port shown with instruments in the trocars

Traditionally, transanal resections were reserved for treatment of benign lesions or malignant lesions in patients not otherwise suitable for classical oncologic resection. With a growing understanding of colorectal tumor biology, disease progression, and advances in medicine, selected malignant tumors are preferentially being treated by local excision transanally to negate the morbidity and mortality of a major resection [4, 6]. As skills and instrumentation evolved, there has been an increasing interest in TAMIS as a key instrument in transanal total mesorectal excision of rectum and in natural orifice tumor extraction (NOTES) procedures; however, these are currently still in the early stages of development [7]. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the transanal total mesorectal excision (ta-TME) of the rectum offers significant advantages, particularly in patients with low-lying tumors, internal sphincter involvement, and especially in the narrow, difficult pelvis typical of the obese male [8].

Indications for TAMIS

The indications for TAMIS in the resection of tumors are the same as for TEMS. This includes benign, premalignant, and selected malignant rectal tumors that are not suitable for endoscopic resection and otherwise would require low anterior resection with or without colostomy. Traditionally, lesions should not occupy more than 30 % of the luminal diameter. However, in the experience of the authors, larger lesions and even circumferential sleeve excisions have routinely been feasible. Well-selected malignancies include tumors less than 3 cm, well-to-moderately differentiated tumors, early submucosal invasion (T1 sm1, sm2), and no evidence of lymphovascular invasion or other poor pathologic features that increase the risk of lymph node metastasis. Patients with advanced disease have also been offered TAMIS for palliation instead of a larger non-curative abdominal procedure. The maximum height of lesions that can be readily accessed and subsequently removed from the rectum varies. However, from our experience of 125 patients requiring rectal tumor resections, we are able to successfully excise all lesions that could be visualized by office proctoscopy without prohibitive patient discomfort. In the same series, several patients had rectal tumor excisions between 14 and 16 cm from the anal verge [4, 9].

The “gold standard” for rectal cancers has traditionally been the low anterior resection (LAR) or abdominoperineal resection (APR) [10, 11]. These operations carry with them significant morbidity and mortality, including anastomotic leak, urinary and sexual dysfunction, fecal incontinence, and almost universally chronic functional changes or low anterior syndrome [12, 13]. In well-selected T1N0 cancers, where the risk of nodal spread is low, TAMIS offers local rectal excision with curative intent and significantly reduced risk of morbidity and mortality. In fact, although several studies have demonstrated increased rates of locoregional recurrence, no comparison has ever demonstrated a survival advantage of radical resection over transanal excision. Ongoing randomized trials should further help delineate this controversial issue (TREC trail, Birmingham University Hospital, UK).

Current indications for TAMIS may also be broadened to include local excision of the “scar”—grossly negative lesions in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer after neoadjuvant therapy—for the purpose of confirming complete local pathological response (ypT0) [14]. Modern neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy can offer up to 20–50 % of patients with rectal adenocarcinoma a complete pathological response [15, 16]. In this subset of patients, LAR or APR can be avoided with fairly low risk. If radical resection is ultimately required following transanal excision because of margin positivity, preoperative understaging, or adverse histological features, this can be performed with no negative long-term impact on survival or cure. Delay in surgery for 6 weeks or longer to allow the mesorectal defect to heal in order to maintain the “holy plane” is recommended.

Preoperative Work-Up

Optimal management of rectal tumors is dependent on obtaining accurate and detailed staging information at the time of diagnosis. Therefore, all patients should undergo adequate oncologic preoperative evaluation including full assessment of the colon by colonoscopy or other radiographic means to rule out synchronous lesions. Digital rectal assessment and proctoscopy/sigmoidoscopy should also be performed in order to determine sphincter tonicity, confirm tumor height, and verify orientation. Local tumor and lymph node staging should be performed by endoanal ultrasound, MRI with endorectal endocoil, or 3-T MRI. Any of these modalities can provide detailed information about tumor depth and lymph node involvement, with MRI providing additional information regarding extramural vascular invasion (EMVI), threatened circumferential resection margin (CRM), and mucin deposits—all of which are negative prognostic markers and can influence treatment options [17–19]. For malignant lesions, metastatic workup with computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is performed as well as consideration of combined CT/PET scan.

Technique (Videos 25.1 and 25.2)

Mechanical bowel preparation is recommend for all patients to maximize visualization of the rectum with minimal contamination. The authors routinely have good results using only two phosphate enemas preoperatively. For inadequate bowel preparation, transanal lavage using a proctoscope or catheter system can be performed, but this technique is not ideal. If visualization is impaired in any way after these maneuvers, the procedure should be terminated and rescheduled with a more thorough preparation. A single dose of intravenous antibiotic is given approximately 30 min before the procedure. TAMIS can be performed in any position. The authors find the high lithotomy position most advantageous for the anesthesiologist and surgeon because it permits the surgeon to perform the operation while sitting comfortably and with minimal neck strain with the viewing monitor placed between the patient’s legs, while providing the anesthesiologist ready access to the airway (Figs. 25.2 and 25.3). The versatility of the TAMIS ports ensures the surgeon can gain good access to the lesion from the lithotomy position regardless the position of the tumor, unlike the TEM system. Positioning in Trendelenburg provides an advantageous view into the rectal lumen throughout the procedure, particularly for anteriorly based lesions that require challenging positioning when using traditional TEM. The authors have used lateral or prone position at times, but when using the TAMIS port, we have not found any intraoperative limitations due to the location of the lesion when using the high lithotomy. In addition, the abdominal cavity may be easily accessed if the need arises intraoperatively.

Fig. 25.2

The patient position is shown during the operation as well as the surgeon positioning

Fig. 25.3

The monitors are placed to provide the most comfortable view

All current transanal access devices are deployed using similar techniques. Gentle two-finger dilatation is performed with or without a perianal block. The port is inserted into the rectum either by hand or ringed forcep with generous lubrication until it seats at the anorectal ring. An obturator is often used to facilitate placement when using the GelPOINT path or Endorec port (Aspide Medicale, La Talaudiere, France). Confirmation of the correct placement is followed by placement of stay sutures through the port eyelets or port itself. Although port dislodgement in a properly deployed device is a rare event, stay sutures can prevent the port from rotating during the procedure and inadvertently changing the location of the camera and working ports, thereby also minimizing trauma to the anorectal canal. Newer-designed access devices permit some variation in port placement to minimize instrument collisions; however, generally three 5 mm ports are placed in a triangular orientation.

Adequate insufflation is generally the most critical component to a successful procedure and ideally achieves a tensely distended rectum for the duration of the procedure. The insufflation port should be placed on the top of the port so that you are not insufflating through any pooled blood. Insufflation is achieved with a standard laparoscopic insufflator at 15 mmHg pressure on high flow, although the pressure may be increased as needed. Pressures as high as 25 mmHg have been attained using bariatric insufflators. To date, there have been no reports of barotrauma or other adverse events to the colon or rectum as a result of insufflation. Complete relaxation with general endotracheal anesthesia is critical to prevent collapse of the rectum or, subtler though equally distracting, bellowing during respiration, the effects of which are magnified during excision of small neoplasms. Recently, spinal anesthesia has been described to perform TAMIS without difficulty; however, any problems should prompt early conversion to a full general anesthetic [9]. Although nearly every surgeon performing TEM or TAMIS has at some point experienced difficulty with poor insufflation, a series of routine laparoscopic troubleshooting strategies will almost always resolve this sufficiently to allow completion of the procedure.

There are multiple options for instrument selection for the procedure. A 5 mm 30° camera is optimal because it provides high-definition visualization for the procedure with the ability to manipulate the angle of the scope based on tumor location. A larger camera and corresponding trocar may be used, but the smaller size is preferable in light of the already small working area and increasingly high-quality picture of smaller laparoscopes. Using a standard colonoscope to provide a wider visual field with more flexibility has been described by Mclemore [20]. Articulating cameras have also been used, but this requires an experienced camera holder and, in most cases, additional expense. The authors have not found that the articulation benefits outweigh the grainier image quality.

In general, the basic instruments should function to grasp and bluntly dissect tissue, to provide cautery, and to evacuate smoke and any blood. The majority of procedures can be performed with a Maryland dissector for fine grasping and either a needle-tip or spatula cautery attached to a suction irrigator. If needed, cautery can be connected to the Maryland dissector for coagulation of a bleeding vessel which commonly occurs in the mesorectal fat. More troublesome bleeding can often be controlled with ease using one of many bipolar energy devices or ultrasonic dissectors. This added luxury might be of significant benefit for more proximal lesions where retraction is limited and bleeding is more difficult to stop. The use of extra-long instruments may prove beneficial to some in minimizing instrument or hand collisions.

Whether using traditional TEM or newer transanal platforms, the quality of resection is paramount. The true marker of outcomes for this procedure is the quality of the specimen. Given the increased rate of resecting malignancies of the rectum with this technique, as well as the malignant potential of adenomas, an accurate, well-executed, technically correct operation with strict indications is imperative. The procedure begins by marking with cautery the intended resection margins on the mucosa 5 mm to 1 cm away from the tumor (Fig. 25.4). A mucosal or full-thickness incision is then performed at the most distal marking (Fig. 25.5). As the tension changes, retraction is frequently adjusted by grasping the tissue as close as possible to the dissection site and using short bursts of monopolar cautery. This is a very dynamic procedure that requires frequent changes in laparoscope angulation and retraction angles. Also, there may be a benefit to exchanging the instruments and camera into different ports to gain a better view or working angle as needed. Direct tumor grasping should be avoided to prevent tumor fragmentation and possible seeding. When performing a full-thickness excision in the correct plane just into the perirectal fat deep to the muscularis propria, the areolar tissue begins to pneumo-dissect from the insufflation pressure. Advancing and retracting the lesion proximally into the rectum while working “underneath” the tumor is the easiest technique. The lesion is slowly encircled while dissecting more proximal in the rectum, frequently reassessing the proximal margin (Figs. 25.6, 25.7, 25.8, 25.9, and 25.10). Finally, the proximal margin is divided and the lesion detached, again facilitated by retracting proximally into the rectum rather than pulling the lesion towards the camera and the port (Fig. 25.11). Specimen extraction should be performed at completion of resection and prior to closure to maintain specimen integrity and avoid accidental proximal migration. The specimen is then pinned in place or marked per surgeon and pathologist preference (Figs. 25.12 and 25.13). The majority of platforms accommodate extraction by allowing removal of the faceplate; however, some ports require removal of the entire device with reinsertion for closure. Irrigation of the excision bed with dilute betadine, presumably for its tumoricidal and bactericidal effects, is a common practice. However, no evidence-based literature exists to support this technique.