Total Pancreatectomy

Michael L. Kendrick

Michael B. Farnell

Introduction

Total pancreatectomy (TP) in both benign and malignant pancreatic disease remains an acceptable alternative in selected patients. Whereas the significant operative sequela and morbidity of this procedure has limited general enthusiasm, increasingly aggressive diabetic management, pancreatic enzyme replacement, surgical techniques, and auto islet cell transplantation continue to spark interest for TP.

In theory, a more radical operation would be expected to provide a more favorable outcome with regard to disease such as intractable pain from chronic pancreatitis or disease free survival after resection of malignancy. In practice, however, superior outcomes have not been consistently demonstrated in cohort studies and Level I evidence does not exist. The treatment of intractable pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis, recurrent acute pancreatitis, and pancreatic malignancy, remains challenging with either medical or surgical approaches and the search for methods to improve outcomes continues. In selected patients, TP appears to be a valid and occasionally necessary alternative and indications may be expanding. Several series have demonstrated increasingly favorable outcomes of TP with appropriate patient selection, surgical technique, and postoperative care.

The potential advantages of TP include:

Elimination of pancreatic leak from the pancreatic remnant observed after partial pancreatectomy.

Amelioration or elimination of intractable pain in recurrent or chronic pancreatitis.

Elimination of recurrent disease such as pancreatitis or intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN).

Avoidance of parenchymal transection with potential tumor spillage in malignancy.

Negates the need for surveillance imaging for potentially recurrent disease of the remnant pancreas.

Disadvantages of TP include complete pancreatic exocrine and endocrine insufficiency as well as the morbidity of the procedure itself. Diabetes after TP may result in considerable morbidity as “brittle diabetes” sets the stage for difficult diabetic management where readmission for hypoglycemic episodes and suboptimal nutrition are not uncommon. With the lack of a pancreatic anastomosis, one would also expect reduced perioperative morbidity compared to partial pancreatectomy. In most series, however,

morbidity after TP ranges from 40% to 60% and is comparable to that observed in partial pancreatectomy and historically, mortality has been higher than for pancreaticoduodenectomy.

morbidity after TP ranges from 40% to 60% and is comparable to that observed in partial pancreatectomy and historically, mortality has been higher than for pancreaticoduodenectomy.

TABLE 7.1 Possible Indications for Total Pancreatectomy | |

|---|---|

|

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONSIndications for TP are listed in Table 7.1. For benign disease such as chronic or recurrent acute pancreatitis, the indication for TP may include relief of intractable pain or prevention of recurrent pancreatitis. In hereditary pancreatitis, TP prevents recurrent pancreatitis and addresses the potential increased risk of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in these patients. In a premalignant condition such as IPMN, TP may be warranted when the disease is diffuse and is considered high risk for malignancy such as in main-duct and multicentric large (>3 cm) branch-duct disease. In addition, completion TP may be indicated for recurrent neoplasm after previous partial pancreatectomy. Whereas the need for TP in the setting of pancreatic adenocarcinoma is uncommon, a completion pancreatectomy to achieve an R0 resection has gained general acceptance. Local factors may occasionally warrant TP for resection of pancreatic neoplasms such as tumor size, location, and presence of marked atrophy of the body and tail with preoperative pancreatic insufficiency. Completion pancreatectomy may also be indicated for management of complications after partial pancreatectomy or to address recurrent neoplasia in the remnant pancreas.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNINGPatients with indications for TP should be screened for prohibitive comorbidities and have an appropriate cardiopulmonary evaluation based on a thorough history and physical examination. Existing comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiopulmonary conditions should be adequately assessed and optimized prior to TP. Appropriate selection of patients for TP also includes assessment of the patient’s ability to comprehend the implications of complete pancreatic endocrine and exocrine insufficiency, and ability to follow the nutritional recommendations and comply with necessary treatment. Ideally, the patient should receive diabetes education preoperatively which facilitates the assessment of patient understanding, may identify compliance issues and enhances the education process in the postoperative period. The patient should also be vaccinated against common encapsulated bacteria (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria Meningitidis) 2 weeks preoperatively when splenectomy is anticipated and should be educated regarding the entity of postsplenectomy sepsis. The anesthesiologist should be alerted to the need for intraoperative glucose monitoring and continuous infusion of insulin. Prophylactic (<24 hours) antibiotics and deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis are used routinely.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

SURGICAL TECHNIQUEPositioning and Exposure

The patient is positioned supine with arms padded and tucked at their side (preferred) or at 90 degrees. A fixed retractor is positioned to allow bilateral cephalad retraction of the costal margins.

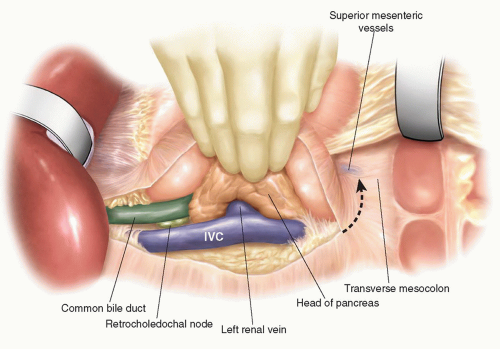

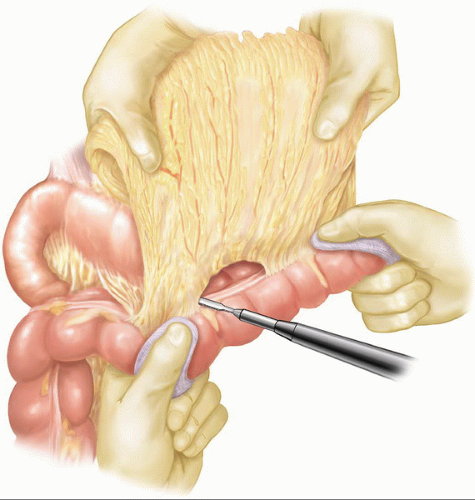

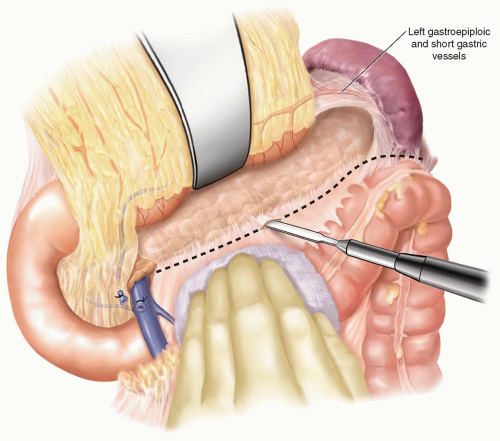

An initial right subcostal or limited upper midline incision is made. A thorough exploration is performed focusing on all peritoneal and visceral surfaces. In the absence of metastatic disease, the subcostal incision is extended to the left. The subcostal retractors are placed and secured to the frame of the fixed retraction system chosen. To maximize the exposure, the inferior abdominal wall flap is secured with a heavy suture to the inferior abdominal wall. Initial dissection is performed to identify evidence of any local findings that would preclude resection. Mobilization of the hepatic flexure of the colon optimizes exposure for kocherization and the eventual distal duodenal dissection. A full kocherization of the duodenum is then performed, extending medially to the aorta (Fig. 7.1). This maneuver allows assessment of the pancreatic head and exclusion of retroperitoneal extension of inflammation or tumor. The left hand is placed around the pancreatic head and the tips of the fingers assess for involvement of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). In the current era of improved CT imaging, these maneuvers will rarely identify evidence of local unresectability, however, they optimize initial exposure and allow improved control needed during dissection of the superior mesenteric and portal vein. Careful inspection of the lesser sac is performed to exclude peritoneal metastases and assess for adjacent organ involvement by inflammation or malignancy. The omentum is dissected off the transverse colon in the avascular plane and the lesser sac is widely exposed (Fig. 7.2). With the anterior surface of the pancreas exposed, the avascular attachments between the stomach and pancreas are divided. The middle colic vein is followed to the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and the gastrocolic venous trunk is identified, ligated, and divided (Fig. 7.3A). This allows safe exposure of the SMV and the inferior border of the pancreas. The middle colic vein is occasionally divided on the basis of necessary exposure or suspected proximity to tumor. Retraction of the colon inferiorly without division of the gastrocolic trunk can lead to inadvertent avulsion and

bleeding. If bleeding is encountered during dissection or ligation of the gastrocolic trunk, the left hand placed posterior to the pancreatic head with the thumb anteriorly will allow direct compression of the SMV to control hemorrhage and facilitate venorrhaphy.

bleeding. If bleeding is encountered during dissection or ligation of the gastrocolic trunk, the left hand placed posterior to the pancreatic head with the thumb anteriorly will allow direct compression of the SMV to control hemorrhage and facilitate venorrhaphy.

With the gastrocolic trunk divided, the SMV can easily be followed to the inferior border of the pancreas. A curved, blunt clamp is used to develop the plane between the SMV and the posterior aspect of the pancreatic neck (Fig. 7.3B). The clamp should advance easily. Difficulty in passing the clamp posterior to the neck of the pancreas should prompt consideration of malignant invasion or significant inflammatory involvement of the superior mesenteric or portal vein. After an initial assessment of the pancreatic neck from the inferior approach, assessment at the superior aspect is performed. The gastrohepatic ligament is incised and the right gastric artery ligated and divided (Fig. 7.4A). The common hepatic artery is dissected at the

superior border of the pancreatic neck and the consistent lymph node in this region is excised. This allows excellent exposure of the origin of the gastroduodenal artery and the insertion of the coronary vein. Ligation and division of the gastroduodenal artery is performed (Fig. 7.4B). Careful dissection at the inferior border of the common hepatic artery near the origin of the gastroduodenal artery will identify the portal vein (Fig. 7.4C). From an inferior approach, a clamp is now advanced anterior to the SMV with the tip oriented in the same direction as the exposed portal vein. Care should be taken to avoid veering to the medial aspect of the vein, as inadvertent injury to the insertion of the coronary vein or splenic vein can occur. A cloth “tape” is passed around the neck of the pancreas which facilitates exposure and retraction of the pancreas (Fig. 7.4D).

superior border of the pancreatic neck and the consistent lymph node in this region is excised. This allows excellent exposure of the origin of the gastroduodenal artery and the insertion of the coronary vein. Ligation and division of the gastroduodenal artery is performed (Fig. 7.4B). Careful dissection at the inferior border of the common hepatic artery near the origin of the gastroduodenal artery will identify the portal vein (Fig. 7.4C). From an inferior approach, a clamp is now advanced anterior to the SMV with the tip oriented in the same direction as the exposed portal vein. Care should be taken to avoid veering to the medial aspect of the vein, as inadvertent injury to the insertion of the coronary vein or splenic vein can occur. A cloth “tape” is passed around the neck of the pancreas which facilitates exposure and retraction of the pancreas (Fig. 7.4D).