Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy With and Without Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration

David B. Renton

W. Scott Melvin

Introduction

Revolutions in the realm of surgery have been predicated on advances in technology. From inhaled anesthetics, to electrocautery, to cardiopulmonary bypass, all have been possible due to scientific advances in the understanding of physiology and physics. This is especially true for even truer for laparoscopy. Beginning in the late 1980s, laparoscopy became the standard of care for the treatment of many surgical diseases, none more so that diseases of the gallbladder. The laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become the gold standard for treatment of acute cholecystitis and symptomatic cholelithiasis. In this chapter we will discuss indications and techniques for performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, intraoperative cholangiogram (IOC), and laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE).

Indications for Laparoscopic

Cholecystectomy

Symptomatic Cholelithiasis is by far the most common indication for cholecystectomy in modern surgical practices. The symptoms of this process are: crampy abdominal pain, usually centered in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) or epigastric area, pain that is brought on or exacerbated by a fatty meal, and the presence of gallstones on imaging studies. With the acceptance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the late 1980s, the threshold for removing the symptomatic gallbladder may have even been has lowered because of the decrease in morbidity associated with the laparoscopic procedure. Careful

patient selection is still necessary to optimize results. Other indications for cholecystectomy include gall bladder polyps or porcelain gallbladder.

patient selection is still necessary to optimize results. Other indications for cholecystectomy include gall bladder polyps or porcelain gallbladder.

Choledocholithiasis with or without associated pancreatitis is also an indication for cholecystectomy. When available, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) preoperatively can clear common duct stones and negate the need for operative common duct exploration. Once the duct is cleared, laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be performed after pancreatic enzymes have returned to normal. If ERCP is not performed preoperatively, IOC should be performed. If stones are detected, either LCBDE can be performed, or postoperative ERCP can be used to clear the duct.

Acute Cholecystitis has been a controversial area for the performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the past. The argument of timing of the operation, either during the acute stage, or waiting 6 weeks to allow a decrease in the inflammation has raged for several years. The current consensus is that cholecystectomy should be performed during the admission for cholecystitis, usually during the first 72 hours of admission. Conversion to an open procedure is more common when dealing with acute cholecystitis than with uncomplicated symptomatic cholelithiasis, but is still within an acceptable rate. Delay in operation risks a repeat attack of cholecystitis, increased hospital stay times, and an equal or higher conversion rate as those operated on within the first 72 hours of presentation.

Biliary Dyskinesia

Patients with no evidence of gallstones on imaging studies and laboratory values with persistent RUQ pain may suffer from biliary dyskinesia. This phenomenon occurs due to lack of contraction of the gallbladder when presented with hormonal stimulus. Nuclear imaging, namely the quantitative HIDA scan, is used for confirmation. Metaanalysis has shown that of patients with an ejection fraction less than 35%, up to 85% of these patients receive relief of symptoms after having undergone laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Patient Selection

While laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be the first choice in all patients for gallbladder removal, some patients provide special challenges which should be considered before beginning the operation. Morbid obesity is a common condition in patients with gallstones. Initial port placement can be a challenge in the patients and should be considered preoperatively to ensure proper equipment is present in the operating room. These patients should be secured to the bed well, as positioning during the operation can cause shifting on the table. Patients with previous surgery, especially upper abdominal procedures should be counseled preoperatively about the possibility of conversion to an open procedure. However, none of these are contraindications for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which remains the procedure of choice for almost all patients undergoing cholecystectomy.

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Since gaining acceptance in the late 1980s, the laparoscopic cholecystectomy technique has not undergone significant change. As with any procedure, there are variations of each step that can be used depending on surgeon preference. The patient is usually positioned supine with arms out. OG tube decompression is recommended to decrease the size of the stomach to ease in visualization. A foley catheter is not necessary in most cases.

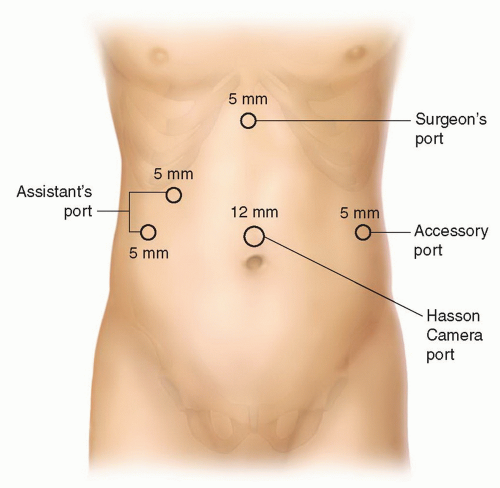

Trocar Placement

The start of any laparoscopic operation begins with safe trocar placement (Fig. 13.1). Placement of the initial trocar aids in successful and safe placement of subsequent trocars. The authors favor a Hasson approach at the umbilicus for initial placement of a 12 mm trocar for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The safety of Hasson technique has been well established. Other options are Veress needle access at the umbilicus or off midline or an optical view trocar access. Supra-umbilical placement of the initial trocar allows a global view of the abdomen, and can be used to rule out any other pathology. The placement of a 12 mm trocar will ease removal of the gallbladder later in the case, especially those laden with large stones. When it comes to trocar placement, the technique that the surgeon is most comfortable with and most proficient with is the best choice. In the setting of previous upper abdominal surgery, the cut down Hasson method is the preferred method, as this allows sweeping down of adhesions around the initial trocar. With this trocar placed, RUQ can be surveyed, and secondary trocars placed safely.

Once initial trocar placement has been successfully achieved, the abdomen is insufflated to 15 mm Hg using CO2. Working trocars are then placed. The trocar placement diagramed shows a standard design used to triangulate on the target structure. The retracting trocars are placed subcostally with one in the right midclavicular line and the second in the right anterior axillary line. The working trocar is placed in the subxiphoid position. This design can be varied depending on surgeon preference, the assistance available to the surgeon, and experience level. A fifth trocar is shown in the left lateral area. This trocar can be added if excessive inflammation is present and the need for repeated irrigation and suctioning is necessary. This fifth trocar can also be used to retract organs that may obstruct the view of the gallbladder and cystic structures such as the transverse colon, duodenum, or omentum.

The subject of trocar size should be mentioned at this point. The need for a second 10 mm or greater trocar, usually placed at the subxiphoid position had been necessary for the completion of this operation. This was due to the need to move the 10 mm camera to this position during gallbladder extraction. It was also necessary because all laparoscopic clip appliers only came in a 10 mm size. With the advances made in current laparoscopic equipment, 5 mm clip appliers are readily available and are usually adequate for ligation of the uncomplicated cystic duct and artery. Optics have also made advances, with current 5 mm 30 degree cameras being equal in image quality to their

larger 10 mm counterparts. This author uses 5 mm ports for all working and retracting ports on a regular basis.

larger 10 mm counterparts. This author uses 5 mm ports for all working and retracting ports on a regular basis.

Steps of the Operation

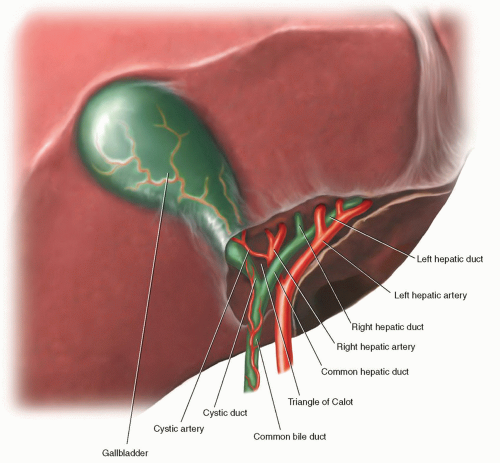

The operation begins with cephalad retraction of the gallbladder. Any adhesions can be taken off the underside of the gallbladder at this point to reveal the infundibulum. Care should be taken to avoid injuring the duodenum and transverse colon as these can be adhesed to the underside of the gallbladder. With the infundibulum exposed, it is retracted laterally to the right. This opens up the Triangle of Calot. If needed, the distended gallbladder can be drained using a laparoscopic needle. Blunt dissection is the undertaken to delineate the cystic duct and cystic artery. Electrocautery and other heat sources should be used judiciously during this portion of the operation to avoid inadvertent injury to surrounding undefined structures. A critical view must be obtained to ensure that these structures are correctly identified before ligation can be undertaken. The critical view is achieved when the neck of the gallbladder is dissected off the liver bed giving a clear view of the liver through the window created around the cystic duct and cystic artery (Fig. 13.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree