The Bassini Operation

Oreste Terranova

Luigi De Santis

Introduction

Edoardo Bassini was an eminent teacher and surgeon at the University of Padua, School of Medicine and Surgery, where he was head of surgical pathology from 1882 to 1888 when he was appointed Chair of Clinical Surgery, a post he held until 1919.

Following extensive study of the anatomy of the inguinal region, he devised a revolutionary method for the surgical treatment of inguinal hernia: The Bassini operation (Fig. 5.1).

Resting on firm anatomic and pathophysiologic foundations, his technique improved on previous empirical methods. And with time, it was proved correct in theory and effective in practice. Much has been said spoken and written on such matters as perhaps on any other. Nonetheless, there is a need to keep abreast of new developments as surgical techniques continue to evolve. In 1986, on the centennial of the publication of Bassini’s article reporting a new approach to inguinal hernia repair, and in homage to Bassini’s work, the Paduan School of Surgery celebrated the occasion with a scientific meeting that gathered such renowned international experts in surgery as Stoppa R, Bendavid R, Nyhus LM, Chevrel JP, and Wantz GE, in which a further contribution to the path pioneered by Bassini was added. At this meeting, the state of the art was defined and the figure of this illustrious physician commemorated.

Biography of Edoardo Bassini

Edoardo Bassini was born into a family of wealthy landowners and patriots in Pavia in 1844. He studied medicine at the University of Pavia, graduating in 1866 at the age of only 22 years.

It is unknown whether he had originally intended to become a surgeon. What is certain is that from an early age he was fascinated by the movement for Italian unification. A friend of the Cairoli brothers, prominent figures in the Italian Risorgimento, he joined the unification movement as an infantry soldier during the third war of independence.

In June 1867, together with the Cairoli brothers, he fought in the battle of Villa Glori near Terni. Numerous historical accounts describe the bayonet assault of 78 men against a troop of 1,000 soldiers. During the battle, Bassini was wounded by a Zouave who took him by surprise and planted a bayonet in his abdomen.

After the battle, Bassini was brought by the few remaining survivors in a cart to the Holy Spirit Hospital, where he was nursed for several months because of a fecal fistula and stercoraceous peritonitis resulting from the bayonet wound to the iliac right fossa

that had pierced the abdominal wall and the intestine. The wounded did not receive particular care because the hospital surgeons believed them inoperable.

that had pierced the abdominal wall and the intestine. The wounded did not receive particular care because the hospital surgeons believed them inoperable.

Thanks to his extraordinary physical resistance, he recovered from the peritonitis but remained stercoraceous probably because of the fecal fistula. He was transferred to Pavia where was placed in the care of Luigi Porta, a great clinical surgeon of that time. During his long stay in the clinic, he gained the friendship and esteem of Porta, who urged Bassini to become a surgeon.

Porta’s encouragement was decisive; he recognized Bassini’s talent for the surgical art and the ingeniousness and the intuition he was beginning to demonstrate in surgical practice.

It was already then, perhaps, that the young student Bassini had begun to think about how best to reconstruct the inguinal canal and restore the anatomy. These experiences, his background, and character would prepare him for a brilliant surgical career.

Descending from a long lineage of farmers, he grew up in an agrarian community, living among men who worked the fields. His family led a comfortable life without luxury. Since his youth he admired the hard work of common laborers, who were poorly paid for the hardships they endured. His love of the land and farming people remained in his heart, though he would later have little contact with rural life.

Accustomed to hard work and sacrifice, he acquired a rigid character, yet earned the respect and admiration of his collaborators. An operating room nurse once said of him, without a grudge but with much pride, that he was a very good person, while he was showing him the shin scars the teacher had given him.

He was surely a generous man; while still alive, gave his farms to his laborers and willed everything he had to the Milan Institute for the Poor which bears his name today. In a few words, he did shun the city’s fashionable salons. Yet he was known as a protagonist and a great admirer of the surgical art. He showed determination when he declined a professorship at the University Parma because the competition was irregular, preferring to remain in La Spezia, where his mentor Porta had found him a temporary post so that he could gain experience.

After attaining a professorship in Padua, he devoted himself to the study of inguinal and crural hernia, reviewing descriptive anatomy and applied anatomy and conducting cadaver studies in which he tested his operating techniques.

On Christmas Eve of 1884, he carried out an operation for inguinal hernia for the first time using the method he had devised and which he would repeat in 1885 and 1886. In 1887, he published his “Nuovo metodo operative per la cura dell’ernia inguinale” in which he reported 262 cases: 251 of which were inguinal hernias including free and persistent hernias, and 11 strangulated hernias, with low mortality, plus 5 recurrences, a surprising result considering that in those days the recurrence rate with any method was over 30%. On the 50th of the operation, his students Fasiani and Catterina wrote: “Half a century has passed and the Bassini method remains a conquest that has survived all criticisms, all attempts at change and daily verification countless times the world over.”

In addition to the original Bassini operation for inguinal hernia, Bassini should also be remembered for having developed other fundamental surgical techniques, including nephropexy, subtotal hysterectomy, ileocolostomy, the cravat incision of the neck for thyroid operations (usually called Kocher’s incision), suprapubic cystostomy, hip disarticulation, intrascapular–thoracic amputation, and a technique for crural hernia.

In 1904, he was appointed senator for life to the Italian parliament. On seeing that his career as teacher and surgeon had ended it course, he said good-bye to his first assistant Mario Donati, who was waiting at the clinic door, and retired to his house in Vigasio. Bassini left to posterity the rational dexterity of his hands and the principle of restoring a diseased organ to its original anatomy and function.

Widely regarded as a meticulous and careful operator, he was considered a great man, teacher, and surgeon in the noblest sense.

The Bassini Operation for Inguinal Hernia

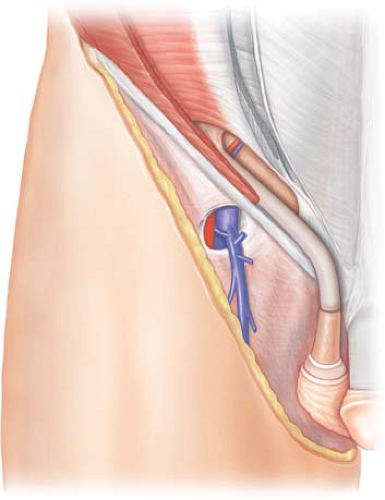

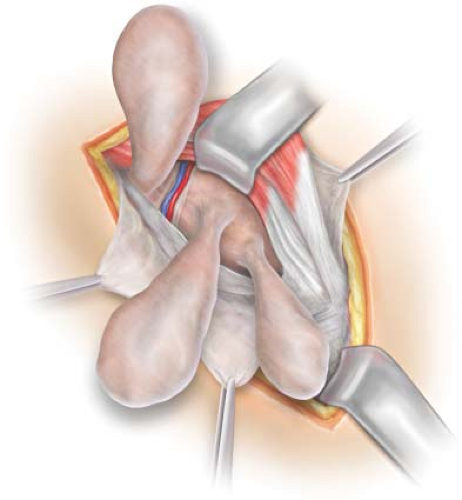

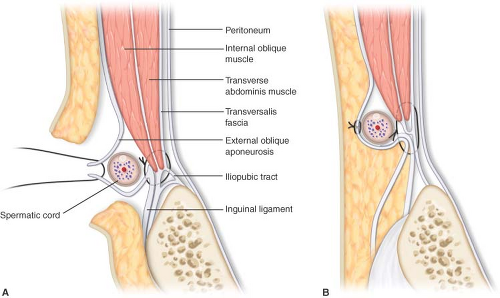

The Bassini operation for the treatment of inguinal hernia entails the reconstruction (Fig. 5.2) of the abdominal wall with a suture that includes three layers (Fig. 5.3) comprising the transversalis fascia, the transversus and the internal oblique muscles superiorly, and the inguinal ligament inferiorly. The method can be easily performed under local anesthesia.

Technique

Incision of the Skin and the Subcutaneous Planes

The cutaneous incision starts at the pubic tubercle, placed laterally to the pubic symphysis, and runs for 8 to 12 cm to the anterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 5.4).

Identified in the subcutaneous adipose tissue, the superficial epigastric vessels are tied and dissected.

The superficial abdominal fascia (Scarpa’s fascia) is then divided.

Release of the external oblique aponeurosis muscle from the innominate fascia (which connects into the spermatic fascia composed of loose cellular tissue), exposes the superficial inguinal ring.

Incision of the External Oblique Aponeurosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree