Surgical Treatment of Chronic Pain after Inguinal Hernia Repair

Bruce Ramshaw

Michael A. Fabian

Introduction

The incidence of chronic pain or discomfort after inguinal hernia repair is much higher than we have previously thought. Fortunately, the great majority of patients who have experienced chronic symptoms after hernia repair have mild or moderate symptoms and do not require an invasive intervention to maintain good quality of life. However, for those patients in whom the pain does negatively affect their quality of life, this post-hernia repair complication can become a nightmare and threaten a person’s livelihood, family, and even their life.

For millennia up until recent times the treatment and management of chronic pain was not only difficult, but forbidden by the church. The inquisition pursued people who attempted to treat pain as witches and heretics, believing they were in alliance with the devil. Those people who ignored the ban on treating pain were tortured, and even killed and burned on funeral pyres.

Queen Victoria was the first woman royalty who ignored the ban and accepted chloroform from her personal physician, John Snow, while she was giving birth to her 8th child. In 1853, in response to this event, The Lancet commented on the use of chloroform for the pain of childbirth, “In no case could it be justifiable to administer chloroform in a perfectly ordinary labour.” However, the use of chloroform to manage the pain of childbirth had become an acceptable practice by the end of the 19th century.

At a medical congress on anesthesia in 1956, Professor Mazzoni confirmed with The Pope that medical treatment for pain was no longer forbidden by the church and that these treatments no longer contradict the common law. To clarify this issue, Pope Pius XII gave a speech to about 500 physicians on February 24, 1957, interpreting religious law and supporting the use of pain relief measures.

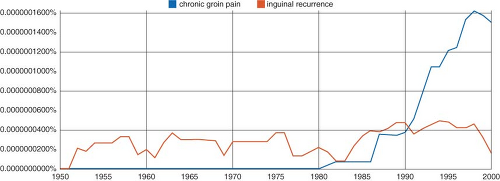

Despite the ability to diagnose and treat chronic pain, we have not yet had great success in achieving a complete understanding of significant relief of pain for the patients who have suffered from severe groin pain after inguinal hernia repair. The increase of “chronic groin pain” in our society is reflected by the incidence of the phrase in our

written language compared to the term “inguinal recurrence” (Fig. 12.1). Google ngrams allow the search for words and phrases from all books digitized by Google. This Google ngram comparison of these two terms reveals a significant increase in use of the term “chronic groin pain” when compared with “inguinal recurrence” over the past 20 years. One reason for the emergence of this problem and our lack of success in treating this form of chronic pain is that it is a complex problem. When a problem is complex, it implies that there are many variables involved, both in creating the problem and in managing or solving the problem.

written language compared to the term “inguinal recurrence” (Fig. 12.1). Google ngrams allow the search for words and phrases from all books digitized by Google. This Google ngram comparison of these two terms reveals a significant increase in use of the term “chronic groin pain” when compared with “inguinal recurrence” over the past 20 years. One reason for the emergence of this problem and our lack of success in treating this form of chronic pain is that it is a complex problem. When a problem is complex, it implies that there are many variables involved, both in creating the problem and in managing or solving the problem.

Figure 12.1 This Google ngram comparison reveals a significant increase in use of the term “chronic groin pain” when compared with “inguinal recurrence” over the past 20 years. |

Chronic groin pain after hernia repair can be a result of patient factors, other diagnoses besides inguinal hernia, the surgical technique and quality of the repair, the mesh and fixation materials used, and even the patient’s experience and environment in the peri-operative and postoperative recovery period. One single factor such as the hernia mesh may or may not play a role in the cause of chronic postoperative pain in any single patient. Because of this complexity, there are many treatment options, both invasive and non-invasive, which may or may not be effective in any given patient, and a combination of treatment options may be required to achieve optimal pain relief.

This chapter will focus on the surgical approach for management of chronic groin pain although some of the other treatment options will also be discussed. Near the end of the chapter, we will also discuss a new model for health care to attempt to deal with complex problems such as chronic groin pain after inguinal hernia repair.

Incidence of Pain after Inguinal Hernia Repair

The reported incidence of chronic groin pain after hernia repair varies widely from a low of 0% to a high of over 50%. Many factors, including who asks the questions, can contribute to the reported incidence in pain. Regardless of the actual incidence, this problem is clearly increasing in awareness (even if only from the cumulative number of patients suffering from this complication year after year) by surgeons and other physicians seeing patients looking for help. If there are 1,000,000 inguinal hernia repairs in the United States each year and 10% of patients experience chronic pain that impacts their quality of life, then 100,000 patients per year are added to the growing group of patients suffering from this problem.

Type of Pain

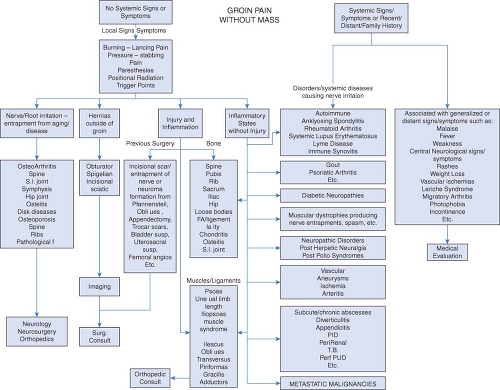

Not all chronic groin pain after inguinal hernia repair is the same. In general, the pain can be divided into two groups, nociceptive and neuropathic. A third group would include pain that was from another cause that is referred to the groin, such as from a previous back injury. Figure 12.2 lists a variety of potential causes of groin pain not related to a hernia bulge.

Nociceptive pain is due to injury to tissue. It is caused by specialized nerve endings that respond to chemical, mechanical, or thermal factors. There are two main subtypes

of nociceptive receptors: Unimodal nociceptors that evoke a sharp, pricking pain, and polymodal receptors that bring about a long lasting dull aching or burning pain.

of nociceptive receptors: Unimodal nociceptors that evoke a sharp, pricking pain, and polymodal receptors that bring about a long lasting dull aching or burning pain.

Neuropathic pain is due to injury to the nerve itself. This type of pain is characterized by partial or complete sensory loss or changed sensory function as a result of damage to the afferent transmission system. Neuropathic pain may be associated with hypersensitivity, including allodynia (a pain response to harmless stimuli), hyperalgesia (an exaggerated response to harmful stimuli) and hyperpathia (a response outlasting harmful stimuli).

In contrast to nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain may persist in the absence of noxious stimuli. It is becoming increasingly recognized that chronic pain can cause long-term changes in the nervous system signaling pathways as well as the processing pathways. This capacity for change in the nervous system, termed neuroplasticity, can result in a perception of pain that persists even after all assumed and previous causes have been removed or alleviated. This is especially challenging and will require a new understanding of managing and treating pain to address this aspect of the pain perception pathway.

Sometimes, especially after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair, a nerve injury (immediate neuropathic pain) is acutely painful and obvious. Direct injury to the nerve from a mesh fixation device can lead to immediate, excruciating pain and paresthesia in the recovery room as the patient emerges from anesthesia. In this case, it is often appropriate to return to the operating room to remove the offending fixation device.

Causes of the Pain

As mentioned in the introduction, the cause(s) of chronic postoperative pain after inguinal hernia repair are many and complex. The patient brings many physical and psychologic variables to the operating room that may or may not play a role in the result of the operation. Some of these variables may not be known by the surgeon or even known by the patient themselves. One common factor identified in several studies is the presence of groin pain prior to the operation. Pre-operative groin pain predicts an increased likelihood of postoperative chronic groin pain. A study by Mazin noted that a majority of patients who suffered from chronic groin pain after inguinal hernia repair were patients on workers’ compensation, suggesting that secondary gain may play a role in this type of complication.

Some of the most studied and reported factors associated with chronic groin pain after inguinal hernia repair include the surgical technique and the mesh and fixation device(s) used to perform the hernia repair. In many studies, the laparoscopic approach has been shown to have a decreased incidence of postoperative chronic groin pain, although in some reports, the incidence after laparoscopic repair may still be as high as almost 30%. Other studies, including a large prospective, randomized controlled trial, suggest that the incidence of inguinodynia after laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repair is actually similar.

Another variable studied is the mesh itself. Although chronic groin pain after non-mesh inguinal hernia repair does occur, a variety of mesh products have been implicated as a factor contributing to chronic groin pain. The proposed mechanism for mesh causing pain is the inflammatory response between the mesh and surrounding tissue including nerves, which can become engulfed in chronic inflammation and/or the mesh contraction which can cause traction injury to nerves and surrounding tissue.

It has been proposed that the higher density, smaller pore size foreign body mesh materials, such as heavy weight polypropylene, may have a higher incidence of causing chronic pain due to the relatively higher amount of inflammatory reaction that they might induce.

Another technical factor that can result in chronic pain is the mesh fixation or tissue closure technique. Using sutures in an open hernia repair and using staples or tacks in a laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair have both been reported to cause or at least contribute to chronic groin pain after inguinal hernia repair, primarily by direct injury or entrapment of a nerve.

Treatment of Chronic Groin Pain after Inguinal Hernia Repair

Non-invasive

For early postoperative and non-severe pain, the initial treatment is rest, ice and/or heat to the groin, and anti-inflammatory medication. A bowel regimen to prevent constipation and bloating may also be helpful. This strategy is appropriate for the first several weeks after surgery unless the pain is severe or significantly worsens within a short period of time, despite conservative treatment.

Pain Management

For more severe pain and pain that worsens or persists for more than a few weeks, it is appropriate to offer the patient more aggressive pain management. Most surgeons are comfortable administering inguinal nerve blocks for diagnostic and possibly therapeutic purposes. If results of the injection are good, but pain returns, additional nerve blocks

may be appropriate. Some patients will obtain sufficient pain relief to return to a full quality of life after one or more nerve blocks.

may be appropriate. Some patients will obtain sufficient pain relief to return to a full quality of life after one or more nerve blocks.

Some surgeons are also comfortable managing chronic pain with a variety of medications. Neurontin, narcotics, Tramadol, anti-depressants, and a variety of other medications have been used to attempt to treat this condition and allow a patient to return to most normal activities (however, these treatments may require activity restrictions while taking the medication).

A referral to a pain specialist (usually trained as an anesthesiologist or neurologist) may also be an appropriate option. A pain specialist who is familiar with this problem will utilize a variety of pharmaceutical, non-invasive and invasive therapeutic options in an attempt to return the patient to an optimal quality of life.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree