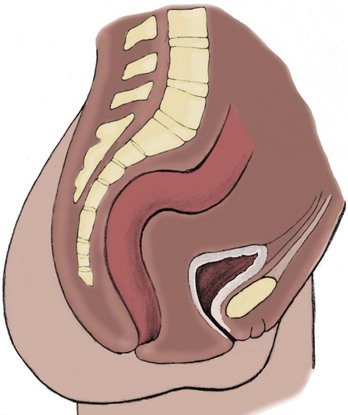

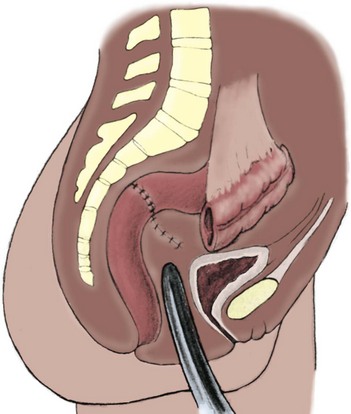

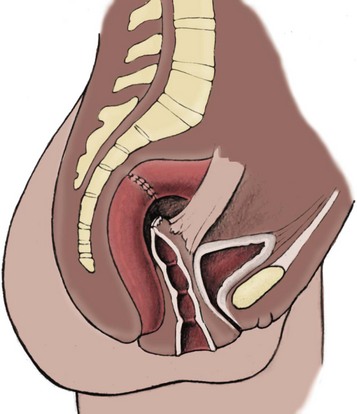

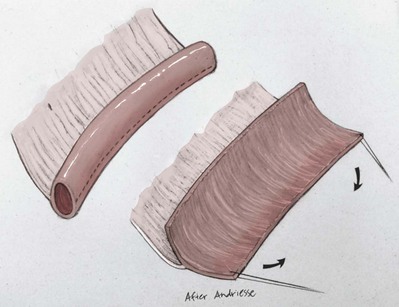

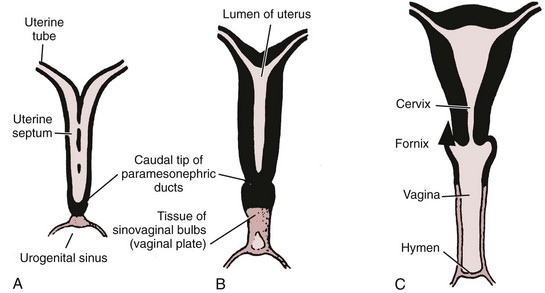

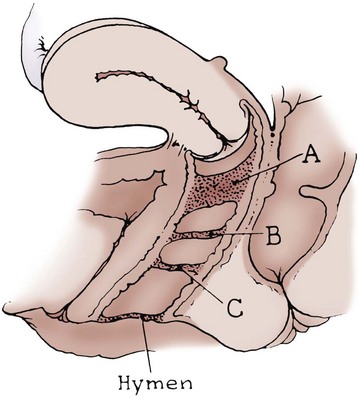

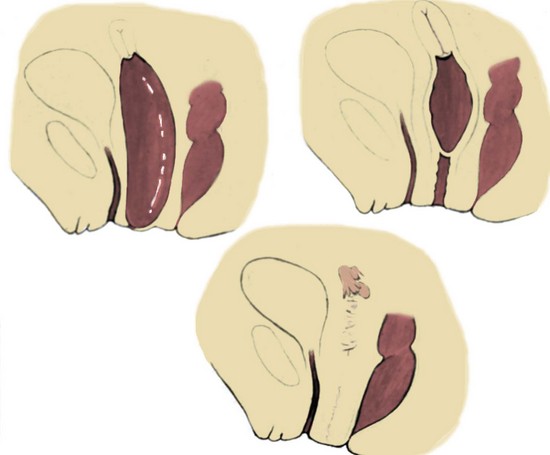

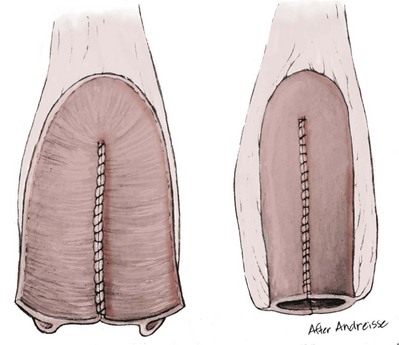

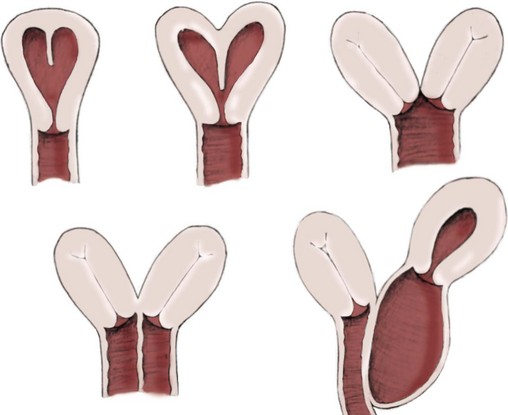

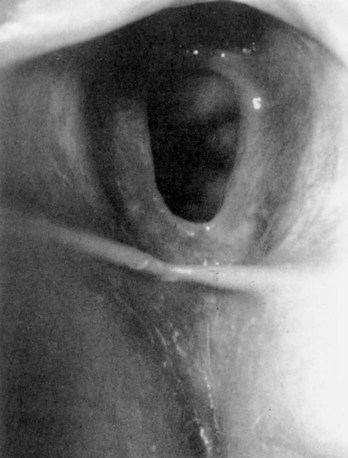

Richard C. Rink, MD, FACS, FAAP, Martin Kaefer, MD, FAAP, FACS As with all other organ systems, genital development in the female occurs in an orderly fashion through multiple complex steps that result in an anatomically and functionally normal child in the vast majority of cases. However, errors in development can occur, from minor, clinically insignificant disorders to severe abnormalities that are devastating to the child and parents. The abnormalities may affect the external genitalia alone or in combination with internal genital anomalies, and in some they may involve other organ systems. In this chapter normal urogenital and anorectal development is briefly described and then anomalies that arise when abnormal development occurs are discussed. Genital ambiguity is often the initial finding in these disorders. Only reconstruction along female lines is discussed; male reconstruction (i.e., hypospadias, chordee repair, and orchiopexy) is discussed in Chapters 130 and 132. Genital reconstruction for disorders of sex development (DSD, formerly intersex) at this time is very controversial. Although significant advances in surgical techniques have occurred since Young’s early work (1937), well-controlled studies with regard to not just cosmetic results but also functional and psychological results are almost nonexistent. Historically, reconstruction of DSD conditions has been surrounded by secrecy, and decisions have been made without scientific studies and often without the patient’s knowledge. Questions regarding genital sensitivity, orgasmic potential, ability for intercourse without pain, gender identity, and psychological aspects in those undergoing early genital surgery currently exist. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss all the pros and cons of this controversy, but it is clear that further studies are warranted. The recently published “Consensus Statement on Management of Intersex Disorders” from a multispecialty international group has been beneficial, but many questions still remain unanswered (Hughes et al, 2006). It is strongly recommended that physicians honestly discuss with the parents of these children all aspects of care, including options, risks and benefits, and negative aspects of both observation and surgical therapy. Although early surgery has been the norm historically, the option of observation with psychological and peer support should be a realistic proposition (Creighton and Liao, 2004). A team of physicians, including a neonatologist, endocrinologist, geneticist, psychiatrist, psychologist, and pediatric urologist, should work with and for the parents in this decision making process. The formation of a gender assignment team has been shown to allow integrated care and more accurate diagnoses in children with DSD (Parisi et al, 2007). Current surgical techniques that are available should surgical therapy be chosen for a child with DSD are addressed in this chapter, but it must be known that absolute indications are rare (Schober, 2004). Other female genital anomalies not associated with genital ambiguity also are discussed. A comprehensive description of genitourinary embryology can be found in Chapters 111 and 133. To foster a deeper understanding of the complex combination of anomalies that can occur in patients with vaginal and cloacal anomalies, a brief review of relevant embryologic events is presented. The cloaca is an endoderm-lined primordial organ that is first apparent at the beginning of the second week of gestation (Grosfeld, 1996). This structure, which represents a confluence of the primitive hindgut (dorsally) and the allantois (ventrally) just before the fourth week of gestation, receives the mesonephric ductal system. The urorectal septum, which first appears during the fourth week of development, serves to separate the urogenital sinus (ventrally) from the anal canal (dorsally) (Moore and Persaud, 1995). The urorectal septum actually consists of two components. The first is the Tourneux fold, which develops along the coronal plane in the angle between the allantois and the hindgut and grows in a caudal fashion toward the cloacal membrane. As this septum nears the cloacal membrane, infoldings of the lateral walls of the cloaca form Rathke plicae, which coalesce in the coronal midline and form the urorectal septum caudally. By weeks 6 to 7 of development the urorectal septum has fused with the cloacal membrane and divided it into a ventral urogenital membrane and a dorsal anal membrane. The fibromuscular node of tissue that results from contact of the septum with the cloacal membrane serves as a critical insertion site for the perineal muscles and as the dividing point of the primitive cloacal sphincter complex into anterior (urogenital diaphragm) and posterior (external anal sphincter) components. The common ontogeny of these two sphincter complexes explains why the pudendal nerve supplies all of these muscles. While the urorectal anlage is undergoing division, the developing mesonephric ducts, which have contacted the cloaca, enter the urogenital sinus near the müllerian tubercle (Churchill and Hardy, 1978). An offshoot of the mesonephric duct, the ureteric bud, extends cranially to induce development of the metanephric blastema. The terminal branch point of the ureteral bud from the mesonephric duct is later absorbed into the wall of the urogenital sinus. Proper incorporation of this complex results in the ureters opening at the lateral aspect of the trigone. As first delineated by Koff in 1933, contact of the uterovaginal primordium with the urogenital sinus forms the müllerian tubercle, which in turn induces the formation of paired caudal endodermal outgrowths called sinovaginal bulbs. Evidence suggests that these outpouchings may in fact represent the terminal segments of the wolffian ducts (Bok and Drews, 1983). Regardless of origin, the cells within these sinovaginal bulbs then proliferate to form a cord of tissue that develops into a distal vaginal plate, which is later canalized in a caudal-to-cranial direction to form the distal aspect of the vagina (Fig. 134–1). The portion of the urogenital sinus distal to the müllerian tubercle subsequently undergoes exstrophy and everts to become the vestibule. As a result of this process, the urethra and vagina acquire separate openings in the vulva. The lumen of the vagina is separated from the cavity of the urogenital sinus by the hymen, an invagination of the posterior wall of the urogenital sinus. Rupture of the hymen should occur during the perinatal period. Figure 134–1 A to C, Formation of the vagina from the sinovaginal bulbs. (From Saler TW. Langman’s medical embryology. 6th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1990.) Key events in skeletal formation occur concurrently with cloacal division and proper formation of the mesonephric and paramesonephric ductal systems (Churchill and Hardy, 1978). The vertebrae develop in a craniocaudal direction, with the lower extremity limb buds developing from condensation of somites 25 through 29. These somites undergo critical differentiation from the fourth through the eighth weeks of development. From the foregoing brief description of caudal embryology it should be evident that a disturbance in segmentation at the level of the caudal somites when the fetus is less than 10 mm in size (fourth to fifth weeks of human development) can affect many different organ systems. In 1960, Duhamel described the association of these “coincidentally” occurring congenital malformations and introduced the term caudal regression syndrome (Duhamel, 1961). Laboratory data with teratogens support the concept that a key event occurs between the fourth and fifth weeks of gestation that results in an error in the simultaneous development of the terminal bowel, kidney, bladder, paramesonephric ductal system, and lumbosacral spine (Mesrobian and Sessions, 1994). The actual inciting event remains unclear, although disordered mesodermal migration, reduced cellular proliferation, and premature apoptosis have all been proposed as potential mechanisms (Kallen and Winberg, 1974; Alles and Sulik, 1993). Elements of the caudal regression syndrome are seen with increased frequency in infants of diabetic mothers, but the exact mechanism is still in question (Deuchar, 1978; Lynch et al, 1995). Specific gene deletions in the homeobox region of the mammalian genome (the region critical for proper mammalian spatial orientation and segmentation) have been shown to result in a constellation of anatomic findings, as predicted by Duhamel (Warot et al, 1997). Because differentiation of the somites progresses in a cranial-to-caudal direction, it would follow that the most complex anomalies (higher anorectal malformations) would occur as a result of aberrations at an earlier stage of development. This also helps explain the greater association of severe upper urinary tract malformations, internal genital duct abnormalities, and spinal anomalies in these patients than in those with less severe cases of imperforate anus. Mesodermal disturbances are not limited to the caudal somites. As seen in the VATER (Vertebral defects, Anal atresia, Tracheoesophageal fistula with Esophageal atresia, and Radial and renal dysplasia) and MURCS (MÜllerian duct aplasia, Renal aplasia, and Cervicothoracic Somite dysplasia) associations, mesodermally derived organs as cranial as the C1 vertebra and tracheoesophageal anlagen can be affected in association with congenital abnormalities of the mesonephric and paramesonephric ductal systems (Quan and Smith, 1973; Duncan et al, 1979). Anomalies of the female reproductive system can be grouped into three main categories: (1) those resulting from either hypoplasia or agenesis, (2) those caused by vertical fusion (canalization abnormalities resulting from abnormal contact of the müllerian structures with the urogenital sinus), and (3) those resulting from lateral fusion (duplication). The clinical manifestations, physical findings, evaluation, and subsequent therapy vary considerably among these groups. Radiographic imaging is of central importance in determining the correct diagnosis. Ultrasonography is helpful not only in identifying the genital anatomy but also in screening for associated upper urinary tract abnormalities (Rosenberg et al, 1986; Fernandez et al, 1996). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered by many to be the “gold standard” for defining internal müllerian anatomy (Fedele et al, 1996; Russ et al, 1997; Lang et al, 1999). It is especially useful for determining the presence or absence of the cervix and the presence of functioning endometrium in complex anomalies. In complicated cases, additional information can be obtained by examination under anesthesia, vaginoscopy, hysteroscopy, and laparoscopy (Major et al, 1997). Obstructive anomalies typically require immediate intervention, but nonobstructive anomalies often do not require surgical intervention unless the patient has reached reproductive age and the condition affects intercourse or adversely affects fertility. Various systems have been proposed for the classification of these anomalies, with the system proposed by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine being the most inclusive (American Fertility Society, 1988). Transverse vaginal septa are believed to arise from a failure in fusion or canalization (or both) of the urogenital sinus and müllerian ducts. The estimated incidence of transverse vaginal septum is 1 in 70,000 females (Banerjee and Laufer, 1998). Many of the patients have amenorrhea and a distended upper vagina. A complete transverse vaginal septum may be located at various levels in the vagina, but there is a higher frequency in the middle and upper third of the vagina. In one large series the distribution was 46% in the upper vagina, 40% in the middle vagina, and 14% in the lower vagina (Fig. 134–2) (Lodi, 1951). The septa are usually less than 1 cm thick and frequently have a small central or eccentric perforation (Suidan and Azoury, 1979). Even in cases in which a perforation is present, significant obstruction and ascending infection can occur. Figure 134–2 Transverse vaginal septum: A, high (upper vagina); B, middle; C, low. (From Yerkes EB, Rink RC. What urologists should know about pediatric gynecologic abnormalities. Contemp Urol 2002;14:12.) Transperineal, transrectal, and abdominal ultrasonography and MRI may be beneficial in establishing the diagnosis and determining the location and thickness of a transverse vaginal septum (Ammann et al, 1983; Doyle, 1992; Meyer et al, 1995; Caloia et al, 1998; Fedele et al, 1999; Lang et al, 1999). MRI can help determine whether a cervix is present so that a high septum can be differentiated from congenital absence of the cervix. Failure to differentiate between these diagnoses can result in significant patient morbidity (Casey and Laufer, 1997). Several surgical treatment modalities have been developed to treat congenital transverse vaginal septa. If the patient’s pain from hematocolpos is manageable, surgery may be delayed with suppression of endometrial activity by a GnRH agonist or continuous oral contraceptives (Beyth et al, 2004). This may allow time for dilatation of the lower vaginal segment, potentially improving the ease of surgical repair. Techniques include simple incision (Brenne et al, 1965; Buttram, 1983), surgical excision of the septum followed by approximation of the corresponding portions of the transversely cut edges of the upper and lower mucosal membranes of the septum (Rock et al, 1982) and the use of Z-plasties involving vaginal mucosa (Wierrani et al, 2003). Vaginal stenosis at the site of resection is the most common complication (Joki-erkkila and Heinonen, 2003). The primary advantage of a Z-plasty is that as the suture line contracts the incision is more likely to take on a longitudinal rather than a transverse orientation. Placement of a vaginal mold subsequent to surgery has been reported to further reduce the risk of postoperative stenosis (Bijsterveldt and Willemsen, 2009). Characteristics of molds for transverse septa are different than those used after a McIndoe vaginoplasty (see later). Whereas a solid mold may be used after a vaginoplasty skin graft (because there is no uterus), the mold used after resection of a transverse septum is ideally hollow to allow egress of menstrual flow. Surgical correction consists of a transverse incision at the level of the hymenal ring. Dissection is carried out through the fibrous area of the absent lower vagina until the upper vagina is reached. As in treatment of a transverse vaginal septum, distention of the vagina with retained menstrual blood products can prove extremely beneficial in that it acts as a tissue expander. After the obstruction is drained and the vaginal mucosa is identified, a pull-through procedure can be performed to bring the distended vagina down to the introitus. The distance to bridge between the vagina and the perineal surface can almost always be successfully managed with perineal skin flaps or simple mobilization of the vagina (or both). Ramenofsky and Raffensperger (1971) described a combined abdominoperineal approach that can be of help in exposing and anastomosing the distal vagina to the perineal skin. Vaginal agenesis, which occurs at an incidence of approximately 1 in 5000 live female births, is congenital absence of the proximal portion of the vagina in an otherwise phenotypically (i.e., normal secondary sexual characteristics), chromosomally (i.e., 46,XX), and hormonally (i.e., normal levels of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone) intact female (Bryan and Nigro, 1949; Griffin et al, 1976). Although Realdus Columbus is credited by some authors as the first to describe a case of vaginal agenesis, Mayer was one of the first to report vaginal agenesis in stillborn children (Mayer, 1829; Lesavoy, 1985). In 1838, Rokitansky reported 19 adult autopsy cases of uterovaginal agenesis, including 3 with associated unilateral renal agenesis. In 1910, Küster recognized urologic associations, such as renal ectopy and agenesis, along with skeletal deformities. Hauser and Schreiner (1961) brought further attention to the frequent association of renal and skeletal anomalies in these patients and stressed the differences between patients with these findings and those with testicular feminization. The Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome, as the entity of müllerian aplasia has come to be known, results from failure of the sinovaginal bulbs to develop and form the vaginal plate (Fig. 134–3). This may be caused by improper induction of the sinovaginal bulbs from the neighboring uterovaginal primordium. Chronologically, the uterovaginal canal develops at a point in embryogenesis during which other critical mesodermally derived organ systems are also forming, which in part explains the many associated findings. Müllerian aplasia has also been associated with maternal deficiency of galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (Cramer et al, 1996). In contrast to vaginal atresia, the hymenal fringe is usually present along with a small vaginal pouch because they are both derived embryologically from the urogenital sinus. (From Yerkes EB, Rink RC. What urologists should know about pediatric gynecologic abnormalities. Contemp Urol 2002;14:12.) Most patients with MRKH syndrome are initially evaluated by the physician after the expected age of menarche because of primary amenorrhea. This syndrome is in fact second only to gonadal dysgenesis as a cause of primary amenorrhea. A minority of patients have cyclic abdominal pain caused by retention of menstrual blood in the uterus. Physical examination reveals absence of the vagina. Inguinal hernia is less common in this disorder than in the testicular feminization syndrome (Schmid-Tannwald and Hauser, 1973). The karyotype is that of a normal 46,XX woman. Radiographic evaluation is indicated to more fully delineate remnant müllerian structures and search for associated anomalies involving the renal and skeletal systems. MRKH syndrome is associated with variable absence or hypoplasia of the cervix, uterus, and fallopian tubes. In approximately 10% of patients, a normal but obstructed uterus or a rudimentary uterus with functional endometrium is present (Murray and Gambrell, 1979; Singh and Devi, 1983; Bates and Wiser, 1985). In one of the largest single series to date, Salvatore and Lodovicci (1978) reported that of 91 patients with vaginal agenesis, almost 25% lacked a uterus, 55% had a solid rudimentary uterus, and the remaining 30% had other abnormalities of this organ. In addition, they demonstrated that although the fallopian tubes were normal in 32% of cases they were rudimentary in almost 50% and completely absent in 10%. Although occasionally cystic, the ovaries were almost always present and functional (Salvatore and Lodovicci, 1978). It was subsequently recognized, based on the morphology of the retained müllerian structures, that MRKH syndrome could be divided into typical and atypical forms (Schmid-Tannwald and Hauser, 1977). In the typical form of MRKH syndrome (type A), the patient has symmetrical uterine remnants and normal fallopian tubes. The atypical form (type B) is characterized by asymmetrical uterine buds or abnormally developed fallopian tubes. This distinction is important because the overwhelming majority of associated findings in other organ systems have been reported to be present with the atypical form whereas in the typical form these findings are usually absent (Strubbe et al, 1992, 1993). The association between vaginal agenesis and developmental abnormalities of the kidney was first recognized by Rokitansky (1838). Approximately a third of patients are found to have abnormal renal findings on intravenous pyelography or ultrasound examination (Strubbe et al, 1993). Renal anomalies are present almost exclusively in patients with the atypical subtype of vaginal agenesis (type B). In Strubbe’s series, 34 of 51 patients with type B anatomy had renal anomalies, but none of the 40 patients with type A (symmetrical) anatomy demonstrated such a deformity (Strubbe et al, 1993). A meta-analysis published by Griffin and associates (1976) demonstrated that the renal anomaly consists of either unilateral renal agenesis or ectopia of one or both kidneys in 74% of those affected. The close proximity of the mesonephric and paramesonephric structures during the early phase of fetal development is thought to be the reason for this frequent association of renal anomalies. Not surprisingly, the converse is also true: the incidence of associated genital abnormalities in female patients with renal anomalies ranges between 25% and 89% (Thompson and Lynn, 1966). Associated congenital abnormalities of the skeletal system have been described in 10% to 20% of cases (Turunen, 1967; Willemsen, 1982; Strubbe et al, 1987). Congenital fusion (failure of segmentation) of the cervical vertebrae is known as the Klippel-Feil syndrome and occurs approximately once in 30,000 to 40,000 live births (Gunderson et al, 1967). An association between this abnormality of cervical somite development and vaginal agenesis was first recognized by Duncan (1977). He proposed the term MURCS association to describe the combination of MÜllerian duct aplasia, Renal aplasia, and Cervicothoracic Somite dysplasia, which many believe is caused by a generalized disordered development of mesodermal differentiation during the fourth week of fetal life (Duncan et al, 1979). Strubbe demonstrated that the Klippel-Feil abnormality was found only in patients with the atypical form of MRKH syndrome (type B). Additional, albeit less common skeletal abnormalities include scoliosis and abnormalities of the hands and face (Willemsen, 1982; Fisher et al, 2000). Unlike müllerian anomalies that are associated with abnormal cloacal septation, vaginal agenesis is not associated with an increased incidence of lumbosacral spinal disorders or occult spinal dysraphism (Gunderson et al, 1967). Key Points Structural Anomalies of the Female Genitalia Both nonoperative and operative treatment options exist for this anomaly. Regardless of the method used, it can be very helpful to have the patient speak with someone who has previously undergone treatment before treatment is initiated (Ingram, 1981). The nonoperative approach, initially popularized by Frank (1938), involves gentle pressure of graduated hard dilators against the perineal surface to create a progressive invagination of the vaginal dimple. Ingram (1981) modified this technique by using a bicycle seat mounted on a stool. The nonoperative approach has greatest success when a vaginal dimple or pouch is already present (Williams et al, 1984, 1985). Gargollo and colleagues (2009) recently reported their experience with 69 females (mean 17.5 years) with vaginal agenesis treated with progressive perineal dilation. Success, defined as the ability to achieve sexual intercourse, vaginal acceptance of the largest dilator without discomfort, or a vaginal length of 7 cm, was achieved in 88% of patients. The authors concluded that progressive perineal dilation should be offered as first-line therapy in adolescents with congenitally absent vagina. Modifications of the Frank technique of perineal pressure have been developed that incorporate the surgical placement of tension sutures to aid in directing pressure from a Plexiglas dilator against the vaginal dimple (Vecchietti, 1979). The mold, often referred to as an “olive,” has sutures attached to it that are guided in a cranial direction through the vesicorectal space into the perineal cavity and brought out through the abdominal wall (Vecchietti technique). Tension is progressively increased via the abdominal wall sutures until sufficient vaginal length has been achieved. To avoid a formal laparotomy, laparoscopic techniques have been described to assist in dissection of the tissue plane for the Vecchietti technique (Borruto, 1992; Gauwerky and Wallwiener, 1992; Fedele et al, 1996, 1999; Brucker et al, 2008). In Fedele and colleagues’ more recent series, all patients were found to have healthy vaginal mucosa, with the average vaginal length being almost 8 cm at 3 months. This technique has had limited use by urologists. If the Frank method has been unsuccessful or is not accepted as a reasonable option by the patient or parents, creation of a functional vagina can be achieved by one of several techniques (Abbé, 1898; McIndoe and Banister, 1938; Hendren and Atala, 1994). The first landmark advance in vaginal reconstruction is attributed to Abbé in 1898. Abbé described dissecting a canal between the rectum and urethra and lining this area with split-thickness skin grafts. This method was later popularized by McIndoe, and the procedure that bears his name has gained wide acceptance in the United States (McIndoe and Banister, 1938). Preoperative preparation consists of full mechanical and antibiotic bowel preparation. A split-thickness skin graft is taken from the buttocks (0.018 to 0.022 inch) and tubularized over a stent (Fig. 134–4). A transverse incision is made at the level of the perineal dimple, and the potential space between the urethra and the rectum is carefully dissected up to the level of the peritoneal reflection. The graft and mold are then inserted into the potential space, and the labia minora are sutured around the stent to prevent extrusion during the initial healing phase (McIndoe, 1950). Many types of vaginal stents have been used for this purpose, including packed gauze, wood covered with a condom, silicone foam, acrylic, various metals, and an inflatable vaginal stent (Concannon et al, 1993; Chen, 1994; Barutcu and Akguner, 1998). The Foley catheter is replaced by a suprapubic catheter, and postoperatively the patient is kept at strict bed rest for 1 full week. A high incidence of postoperative vaginal stenosis necessitates postoperative vaginal dilation (Ingram, 1981). Excellent patient satisfaction has been reported in most large series (Martinez-Mora et al, 1992; Strickland et al, 1993; Alessandrescu et al, 1996). Other options for creation of a neovagina with local tissues include the use of full-thickness skin grafts from the buttocks or full-thickness skin flaps based on the labia majora. Those who champion the use of full-thickness skin grafts report a lower incidence of graft contracture than when split-thickness graft techniques are used (Sadove and Horton, 1988). The Williams vaginoplasty involves the creation of a vaginal pouch from the labia majora (Williams, 1964). The combination of this procedure and Frank-type dilation along the vaginal axis can provide a satisfactory result. Many other surgical procedures have been developed for creation of a functional neovagina with various muscle flaps (e.g., pudendal thigh, rectus abdominis, buttock) (McCraw and Massey, 1976; Lilford et al, 1989; Dumanian and Donahoe, 1992; Wang and Hadley, 1993; Joseph, 1997). The pelvic peritoneum and human amnion are two other donor sites that have been used to create a neovagina (Davydov, 1977; Ashworth et al, 1986; Morton and Dewhurst, 1986; Tamaya and Imai, 1991; Marquis et al, 2008). Baldwin first described the use of bowel for creation of the vagina in 1907. The procedure involved anastomosis of a U-shaped segment of sigmoid colon to the perineum with subsequent division of the intervening septum (Hensle and Dean, 1992). Additional experience with this technique was reported by Fall in 1940, but it did not gain widespread acceptance until the 1970s because of high patient morbidity and mortality (Fall, 1940; Pratt, 1972). Subsequent improvements in technique and postoperative care resulted in renewed enthusiasm for these techniques (Turner-Warwick and Kirby, 1990; Hendren and Atala, 1994; Hensle and Reiley, 1998; Tillem et al, 1998). Sigmoid, cecum, and small intestine have all been used successfully for the creation of a functional neovagina. The day before surgery, the patient undergoes full mechanical and antibiotic cleansing of the alimentary tract. The procedure is performed with the patient supine, the legs spread, and the knees bent (frog-leg position). In an older child, Allen stirrups can be used. For a sigmoid vaginoplasty, the intra-abdominal portion of the procedure begins by first identifying an appropriate length of distal sigmoid with a blood supply that will comfortably reach the perineum (Figs. 134-5 and 134-6). The distal end of the proposed segment is then divided and anastomosed to the perineum (Fig. 134–7). An intervening segment of sigmoid (approximately 3 cm) is then excised to create a space between the oversewn proximal edge of the bowel vagina and the end of the sigmoid, which is anastomosed to the rectum. This maneuver prevents an overlap of suture lines and thereby has the potential advantage of limiting the incidence of fistula formation. The bowel vagina is thereafter fixed to the posterior peritoneum to prevent prolapse. Gosalbez has recently described a modified Monti technique of bowel detubularization for vaginal replacement that can aid in allowing the segment to reach the perineum. By opening the colonic segment close to its mesentery along one side of the bowel and then retubularizing in a Heineke-Mikulicz fashion as described by Monti, the reconfigured segment allows for the mesentery to be located at the most cranial end of tube and allows the caudal end to extend more distally (Gosalbez, 2009). Although the authors have had the most success with the sigmoid, a small-bowel segment may be chosen with a vascular pedicle that is of adequate length to reach the perineum. After isolating an appropriate length of ileum and reestablishing bowel continuity, the segment is detubularized and reconfigured in a conical arrangement to provide increased internal diameter (Figs. 134-8 and 134-9) (Hendren and Atala, 1994). The segment is then brought down to the perineum and sewn in place, as for a sigmoid neovagina. To avoid a formal laparotomy, laparoscopically assisted techniques have been described for harvest and delivery of the bowel segment to the perineal location (Ota et al, 2000). Figure 134–9 Bowel vagina: reconfiguration of the ileal segment to create a larger luminal diameter. The functional results of bowel vaginoplasty have been excellent. Of the 65 patients reported by Hendren, 16 experienced mild eversion of the bowel segment, which in every case was amenable to simple trimming. Eight patients experienced mild stenosis that was later corrected by appropriate Z-plasties to increase the circumference of the mucocutaneous junction (Hendren and Atala, 1994). Patient satisfaction is high, and the majority of patients who are old enough to engage in sexual relations are able to achieve adequate coitus (Hensle and Reiley, 1998). Stenosis has been reported more frequently after the use of ileum (Hensle and Dean, 1992). This higher stenosis rate may be due not only to the more narrow ileal lumen but also to the limited mobility of the small bowel mesentery. As a result, the authors and others believe that large intestine is the bowel segment of choice. Two specific indications for use of an ileal segment for bowel vaginoplasty are previous irradiation of the deep pelvis and the absence of large intestine (i.e., cloacal exstrophy). When ileum is used, various methods of reconfiguration can be used to increase the diameter (Hendren and Atala, 1994). Advantages of a bowel vagina over the McIndoe procedure include the lubricating properties of mucus (which may help facilitate intercourse) and the decreased incidence of postoperative contracture (and hence the reduced need for postoperative dilatation). Disadvantages include the frequent need to wear pads because of the chronic vaginal discharge. Daily douching may be necessary to evacuate the mucus. Finally, the potential transmission of blood-borne pathogens such as hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus may be increased (in comparison to a squamous epithelium-lined vagina) because of the poor barrier effect of the gastrointestinal tract. All patients undergoing creation of a functional vagina with perineal skin require annual examination because there have been reports of condylomata acuminata and squamous cell carcinoma involving grafts (Duckler, 1972; Rotmensch et al, 1983; Buscema et al, 1987). Annual examination of the bowel vagina is also indicated because adenocarcinoma has been identified after this procedure (Andryjowicz et al, 1985). The optimal timing of surgery remains a source of debate. The majority of surgeons who favor the McIndoe procedure for construction of a neovagina believe that it is better to wait until adulthood to perform the procedure because a degree of maturity is required to consistently perform daily dilatations. Many surgeons who favor the use of bowel for neovaginal reconstruction do not believe that vaginoplasty should be deferred until the patient reaches adulthood. Hendren and Atala (1994) believe that delaying creation of a neovagina until adulthood may be psychologically traumatic to a young girl. The authors have based timing on the underlying diagnosis and need for a neovagina. Cervical agenesis is an uncommon disorder that is associated with symptoms common to other obstructive entities of the female reproductive tract (i.e., primary amenorrhea, cyclic or chronic abdominal pain). Failure to establish the correct diagnosis and thereby choose the appropriate method of surgical intervention can be fraught with disaster and possible patient mortality. MRI is the most useful radiographic modality in establishing this diagnosis (Fig. 134–10). In many circumstances the patient is best served by hysterectomy with subsequent vaginal replacement by one of the previously described techniques (Rock et al, 1984; Cukier et al, 1986). Successful direct anastomosis of the neovagina to the uterine remnant has been reported. Deffarges and coworkers (2001), in describing their experience with uterovaginal anastomosis, reported a 40% pregnancy rate in patients attempting to conceive. Cerclage was performed in only one case. All deliveries were by cesarean section. Although this procedure appears to be successful in the majority of cases, absence of the normal endocervical barrier can leave the patient predisposed to the development of life-threatening ascending infection (Maciulla et al, 1978; Niver et al 1980; Casey and Laufer, 1997). Key Points Vaginal Replacement Surgery In cases in which it has not been possible to successfully achieve continuity between the uterus and vagina, in-vitro fertilization plus transmyometrial embryo transfer has been performed, with subsequent delivery of a healthy fetus by cesarean section (Anttila et al, 1999; Lai et al, 2001). If this option is considered, hormonal blockade of the endometrium until the time at which the patient desires to initiate a pregnancy is indicated to minimize discomfort and reduce the incidence of endometriosis from retrograde menstrual flow in the fallopian tubes. True duplication of the uterus is a rare event. This anomaly results from duplication of the müllerian ducts and subsequent doubling of the reproductive structures on one or both sides. The much more frequently encountered anomaly of uterine didelphys consists of two separate uterine cavities and cervices as a result of failed resorption of the common medial wall of the paired müllerian duct structures during development. Although up to 75% of patients also have a septate vagina, most have adequate reproductive outcomes and do not require surgical intervention. If later in life the patient experiences difficulty with intercourse, vaginal delivery, or the need to use two tampons, surgical excision of the vaginal septum should be undertaken. If only the most cranial portion of the septum remains, a bicornuate uterus will result. The vagina is typically normal, and surgical incision of the uterine septum is rarely indicated except in cases of recurrent pregnancy loss (DeCherney et al, 1986). Although the majority of obstructive lesions are caused by abnormalities in vertical fusion, occasionally an obstructive process can be encountered in the context of an abnormality in lateral fusion (Figs. 134-11 and 134-12). More than 50 cases of uterus didelphys with a unilateral imperforate vagina have been reported in the world’s literature (Allan and Cowan, 1963; Burbige and Hensle, 1984). As with other obstructive disorders, the patient may have cyclic or chronic abdominal pain. However, unlike other obstructive processes, duplication anomalies with unilateral obstruction do not result in primary amenorrhea. On physical examination, a unilateral abdominopelvic mass that terminates in a bluish bulge in the lateral vaginal wall is often appreciated (Eisenberg et al, 1982). Abdominal ultrasonography and MRI are both excellent at defining the anatomy in a suspected case of unilateral noncommunicating uterine horn. Renal anomalies are frequently encountered on the side ipsilateral to the obstructed system, with renal agenesis being the most common (Eisenberg et al, 1982; Tridenti and Bruni, 1995). A prompt and accurate diagnosis is necessary to prevent injury to the genital organs as a result of chronic cryptomenorrhea and endometriosis. Treatment consists of wide incision of the vertical vaginal septum to release the entrapped menstrual blood. (From Yerkes EB, Rink RC. What urologists should know about pediatric gynecologic abnormalities. Contemp Urol 2002;14:12.) Acquired vaginal obstruction may be secondary to a number of ritual female genital mutilation procedures that are widespread in many countries in Africa (stretching in a band from the Horn of Africa through Central Africa to parts of Nigeria), the Middle East, and Muslim populations of Indonesia and Malaysia (Toubia, 1994; Dorkenoo, 1996). Although similar procedures were prescribed to U.S. and British women during the 19th century for the treatment of ailments ranging from epilepsy to lesbianism, all forms of genital mutilation are now illegal in these Western countries. Often referred to as “female circumcision,” the procedure continues to affect an estimated 80 to 110 million women worldwide (Toubia, 1994). The age at which this procedure is performed ranges from birth to just before marriage. However, it is typically performed on preadolescent children between the ages of 4 and 10 years, most commonly at age 7 (American Medical Association, 1995). The procedure is usually performed without anesthesia in the context of a ceremony designating the rite of passage into adult society (American Medical Association, 1995). The extent of the mutilation varies according to ritual, but the practice predates Islam and is therefore not part of a religion (McCaffrey et al, 1995). In many countries the women have a deinfibulation procedure performed just before consummating the marriage. The type of mutilation ranges from simple excision of the prepuce of the clitoris (termed sunna) to complete excision of all elements of the vulvar region (McCaffrey et al, 1995). Toubia (1994) classified the more extensive female genital mutilation procedures according to the amount of tissue destruction: Figure 134–13 Female infibulation. Note the scarred labia majora with only a pinhole opening for the passage of menstrual fluid and urine. (From Gonzales ET, Bauer SB, editors. Pediatric urology practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. p. 599.) Closing of the introitus, typically referred to as infibulation or pharaonic circumcision, is performed by a variety of means, including absorbable and nonabsorbable suture materials, thorns, and twigs. The child’s legs are then bound for up to 40 days to ensure secondary healing in the ventral midline (McCaffrey et al, 1995). The physical, psychological, and reproductive repercussions of these forms of genital mutilation are numerous and include immediate destruction and infection of local tissues (e.g., rectum, urethra). Long-term risks include chronic pain, recurrent urinary tract and vaginal infections, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and apareunia. For individuals with the most narrowing, additional “surgeries” to revise the introital opening may be necessary for both intercourse and vaginal delivery (Aziz, 1980; Toubia, 1994). The physician must be sure to specifically reassure the girl that the examination will not be painful. With the child in the frog-leg position, the physician should note the size of the clitoris, the configuration of the hymen, the location of the urethra, and the character of the interlabial mass (e.g., smooth, lobulated, hemorrhagic). To aid in visualization, the labia majora can be gently grasped and pulled caudally and laterally to enable funneling of the introitus and vagina (the so-called pull-down maneuver) (Fig. 134–14). Determining the nature of a specific mass can be facilitated by establishing the location of expected anatomic landmarks. In certain circumstances, the relationship of the mass to the vagina and urethra can be improved by gentle placement of a lubricated cotton applicator posteriorly or placement of a small feeding tube within the suspected urethral orifice, or both. Although an otoscope, nasal speculum, or pediatric vaginal speculum can be useful in evaluating the vagina while the patient is awake, complaints of vaginal origin (i.e., vaginal discharge or bleeding) are often best investigated with a carefully performed examination and vaginoscopy under anesthesia. Renal-pelvic ultrasonography can be a useful adjunct in confirming or establishing the diagnosis in a few of these disorders. Labial adhesions, also referred to as labial agglutination, and synechia vulvae are the most common interlabial abnormality identified in children, ranging in incidence from 0.6% to 1.8% (Norbeck et al, 1993; Leung et al, 1993). This condition occurs predominantly in the first 2 years of life, with a peak incidence between 13 and 23 months (Fig. 134–15). Fusion of the labia minora originates at the posterior fourchette and progresses for a variable distance toward the clitoris. It is important to differentiate this condition from the more serious entity of fusion of the labia majora, as is seen in certain DSDs. It has been hypothesized that hypoestrogenism may play a role in adhesion of the labia minora. Labial adhesions have not been reported in newborn children, presumably because of the protective effect of maternal estrogen (Leung et al, 1993). However, the etiologic role of the hypoestrogenic state has been brought into question by a number of authors (Caglar, 2007; Pulvino et al, 2008). Caglar (2007) measured circulating estradiol levels in 59 girls with labial adhesions and 60 control patients. He demonstrated no difference in the circulating level of estrogen in these two patient groups. Recently it has been shown that estradiol may enhance wound re-epithelialization by promoting heparin-binding epidermal growth factor production in keratinocytes (Kanda et al, 2005). If there is a beneficial effect of topical estrogen it may be to promote healing after the adhesions have been separated. Nonhormonal factors may play an etiologic role in the formation of labial adhesions (Papagianni and Stanhope, 2003). Local irritation and tissue trauma appear to be important inciting events in many cases. Adhesions can rarely be associated with sexual abuse; in such cases, additional physical findings are often noted, including hematoma and lacerations (McCann et al, 1988). Although labial adhesions are usually asymptomatic, urine pooling within the vagina may lead to postvoid dribbling and perineal irritation and may make it difficult to obtain an accurate urinalysis or perform radiographic procedures. Most children with labial adhesions do not require treatment unless they are symptomatic. With the rate of spontaneous resolution reported to be as high as 80% within 1 year, asymptomatic labial adhesions can comfortably be observed (Pokorny, 1992). When necessary, treatment ranges from the topical application of various steroids to surgical division. The topical application of conjugated estrogens has been reported to be successful in separating adhesions in up to 90% of patients (Leung et al, 2005; Khanam et al, 1977). Concern over the possible side effects of breast budding and hyperpigmentation from prolonged use of conjugated estrogen led Myers and associates (2006) to treat a cohort of 19 prepubertal patients with topical betamethasone (0.05%). The authors reported success in 13 (68%) patients after administering one to three courses of twice-daily therapy for 4 to 6 weeks. It is important to have the family place the cream directly on the labia minora. In addition, it is helpful to have the family perform the pull-down procedure a few times a day to put light stress on the midline adhesions and hence facilitate their separation. If topical therapy is not successful, manual separation in the outpatient setting may be indicated. After the application of EMLA cream to the introitus, gentle pressure is applied to the thin connecting membrane with the use of a lubricated probe. Rarely, in cases in which the adhesions are extremely dense, surgical division is required. Although one group has recently advocated oversewing the separated edges with 7-0 chromic sutures (Nurzia et al, 2003), the authors have not found this to be necessary if the family is properly educated about keeping the labia separated (see Fig. 133–14) after the procedure. Recurrence rates appear to be similar when comparing children who have undergone manual separation (16.7%) versus surgical separation (15.4%), emphasizing the importance of having families continue to separate the labia after separation has been achieved (Muram, 1999). Key Points Nonobstructive Genital Anomalies Paraurethral cysts in a neonate represent a dilatation of the periurethral glands, which are located just inside the urethral meatus (Fig. 134–16). These glands are homologues of the male prostatic glands and number between 6 and 30, with the two largest termed the periurethral glands of Skene (Skene, 1880; Gottesman and Sparkuhl, 1979). In a neonate the periurethral glands occasionally respond to maternal estrogen and secrete mucoid material, which can result in cyst formation. The main distinguishing feature of this condition is displacement of the urethral meatus by the mass and, consequently, an eccentric urinary stream. If the urethral meatus can be identified as being completely separate from the mass, radiographic evaluation is not needed to confirm the diagnosis (Nussbaum and Lebowitz, 1983). These cysts are frequently self-limited and often rupture spontaneously. If they are persistent, drainage by a small needle is easily achieved at the bedside. Figure 134–16 Paraurethral cyst. (From Yerkes EB, Rink RC. What urologists should know about pediatric gynecologic abnormalities. Contemp Urol 2002;14:12.) Gartner duct cysts represent cystic remnants of the wolffian duct system and can be found along the anteromedial wall of the vagina (Pradhan and Tobon, 1986). A cystic structure related to a Gartner duct cyst is a covered ectopic ureter that enters into the vagina (Rosenfeld and Lis, 1993; Holmes et al, 1999). Embryologically, the ureter would not be expected to enter the vagina. However, an ectopically located ureter may end in a segment of the wolffian duct system, which in a female is represented by a Gartner duct cyst. In most instances this cystic structure spontaneously ruptures before delivery, thereby resulting in direct communication between the ectopic ureter and the vagina. However, if the surface epithelium fails to rupture, a covered, urine-filled cyst will exist within the vagina. Intraoperative injection of the cystic structure with radiographic contrast material may be beneficial in outlining the anatomy (Fig. 134–17). Incision of the cystic structure relieves the obstruction. As a general rule, the more ectopic the insertion of the ureter, the more dysplastic the segment that it drains will be. However, renal moieties that ectopically insert into the vagina may produce urine. Subsequent upper pole heminephrectomy may be indicated if the child has significant urine production from the segment (resulting in incontinence) or an infection develops after decompression. Hymenal skin tags are virtually a normal finding and are rarely symptomatic (Figs. 134-18 and 134-19). When symptomatic (i.e., bleeding), they should be excised to ensure that they do not represent a malignancy and to provide symptomatic relief. Congenital abnormalities of the hymen are not uncommon and range from an imperforate hymen to one with numerous small microperforations. Figure 134–18 Normal hymenal ring. (From Emans SJ. Office evaluation of the child and adolescent. In: Emans SJ, Laufer MR, Goldstein DP, editors. Pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998.) Imperforate hymen is probably the most common congenital obstructive anomaly of the female reproductive tract. The diagnosis is most frequently made at birth by noting the presence of a bulge along the posterior aspect of the introitus, which represents retained fluid within the vagina, or by palpation of a suprapubic mass from a distended vagina (Fig. 134–20). The buildup of retained vaginal secretions in the neonatal period, which imparts a whitish appearance to the bulging hymenal membrane, is caused by maternal estradiol stimulation. If the diagnosis is made after the neonatal period, the mucus will often have been reabsorbed and a bulge in the hymenal membrane may no longer be evident. On occasion, the diagnosis is not made until the adolescent period, when the patient experiences amenorrhea and possibly cyclic abdominal pain. In these circumstances, a bluish bulging hymen may be observed on genital inspection and a mass will be appreciated on rectoabdominal palpation. Figure 134–20 Imperforate hymen. Note the significant distention from vaginal secretions. (From Yerkes EB, Rink RC. What urologists should know about pediatric gynecologic abnormalities. Contemp Urol 2002;14:12.) In newborns, repair by incision of the hymenal tissue at the bedside is performed in the transverse direction to avoid inadvertent extension of the incision anteriorly or posteriorly (which might injure the urethra or rectal structures). Simple aspiration of the vagina without a definite drainage procedure should be discouraged because incompletely evacuated material may be prone to ascending bacterial growth. In pubertal girls, general anesthesia with excision of excess hymenal tissue may be indicated (Fig. 134–21). Figure 134–21 Intraoperative photograph showing incisional drainage of an imperforate hymen. (From Yerkes EB, Rink RC. What urologists should know about pediatric gynecologic abnormalities. Contemp Urol 2002;14:12.) Urethral prolapse generally involves complete circumferential eversion of the urethral mucosa at the level of the external urethral meatus (Fig. 134–22) (Lowe et al, 1986). This entity, which was first described by Solinger in 1732, occurs most often in prepubertal black girls and in postmenopausal white women (Epstein and Strauss, 1937; Richardson et al, 1982). Various causes that have been proposed for urethral prolapse include hypoestrogenism (Desai and Cohen, 1997), abnormal connections between the inner longitudinal and outer circular muscle layers of the distal urethra (Lowe et al, 1986), and episodic increases in intra-abdominal pressure (Lowe et al, 1986; Desai and Cohen, 1997; Valerie et al, 1999). The most common initial complaint is bleeding from the edematous and friable mucosa, which results in blood spotting on the underwear (Richardson et al, 1982; Chaouachi et al, 1989). Urethral prolapse is easily recognized as a doughnut-shaped mass with the urethral meatus at the center. If the diagnosis can be confirmed by passing a urethral catheter, radiographic evaluation is not indicated (Nussbaum and Lebowitz, 1983). Treatment options include observation, topical corticosteroids, and surgical excision (Redman, 1982; Fernandes et al, 1993). Sitz baths may be helpful. Nonoperative treatment may lead to spontaneous reduction of the prolapse, but a recurrence rate of up to 67% has been noted (Jerkins et al, 1984). Many methods of surgical repair have been described. Circumferential excision of the redundant mucosa with subsequent suturing of the normal urethra to the vestibule is the procedure of choice (Devine and Kessel, 1980). Other methods, including ligation over a transurethral catheter with subsequent sloughing and cryosurgery, should be discouraged (Owens and Morse, 1968; Klaus and Stein, 1973). Figure 134–22 Urethral prolapse. (From Yerkes EB, Rink RC. What urologists should know about pediatric gynecologic abnormalities. Contemp Urol 2002;14:12.) An ectopic ureterocele is a cystic dilatation of the terminal portion of the ureter that occurs predominantly in white females (Mandell et al, 1980). Approximately 90% of ectopic ureteroceles are associated with the upper pole of a duplex collecting system. Although they normally remain positioned proximal to the bladder neck, some may prolapse through the urethra during micturition, almost always in infancy, and result in urinary retention and a relative urologic emergency (Gingell et al, 1971). Depending on the length of time that the ureterocele has been prolapsed, it may vary in color from pink to dusky purple (Fig. 134–23). If a prolapsed ureterocele is in the differential diagnosis, bladder-renal ultrasonography should be performed to look for upper pole hydronephrosis in a duplicated collecting system (Fig. 134–24). Figure 134–24 A ureterocele evident on ultrasonography of the bladder. (From Yerkes EB, Rink RC. What urologists should know about pediatric gynecologic abnormalities. Contemp Urol 2002;14:12.) The pediatric equivalent of a urethral caruncle, namely, a urethral polyp, is a rare lesion that can be manifested as an intralabial mass (Fig. 134–25). The etiology of true lesions has not been completely elucidated, but in a young child they probably represent either hamartomatous growth or a response to inflammation. Figure 134–25 Urethral polyp: probe in urethra and Babcock clamp on urethral polyp. (From Yerkes EB, Rink RC. What urologists should know about pediatric gynecologic abnormalities. Contemp Urol 2002;14:12.) The authors described two young girls with an interlabial mass. Histologic examination of each excised mass revealed a benign urethral polyp covered with transitional and squamous epithelium (Klee et al, 1993). Urethral polyps should be included in the differential diagnosis of an interlabial mass in young female patients. Vaginal rhabdomyosarcoma is most often manifested as a grapelike cluster of tissue emanating from the posterior aspect of the vestibule (Fig. 134–26). The mean age of patients with primary vaginal tumors is younger than 2 years (Hays et al, 1988). Of all the female genital tract primary tumors, vaginal primary tumors appear to have the best prognosis. This excellent prognosis is thought to be a result of predominance of the embryonal cell type and relatively early detection because of symptoms of bleeding (Hays et al, 1988). Once a tissue diagnosis has been made by biopsy, proper staging with abdominal and pelvic computed tomography, chest radiography, and bone marrow biopsy is critical to optimal stratification of these patients into treatment protocols (Hays et al, 1985). Advances in chemotherapy have led to a reduction in the role of surgery for this disease with each subsequent Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study (IRS) trial: IRS-I, 100%; IRS-II, 70%; IRS-III, 30%; and IRS-IV, 13% (Andrassy et al, 1999). After chemotherapy, local resection may be required, but unlike other malignancies of the vagina, wide excision of the involved organ has no role except for persistent or recurrent disease (Hensley, 2000). Figure 134–26 Vaginal rhabdomyosarcoma. (From Yerkes EB, Rink RC. What urologists should know about pediatric gynecologic abnormalities. Contemp Urol 2002;14:12.)

Female Reproductive and Caudal Embryology

Structural Anomalies of the Female Internal Genitalia

Obstructive Genital Anomalies

Abnormalities of Vertical Fusion

Transverse Vaginal Septum

Vaginal Atresia (Distal Vagina)

Vaginal Agenesis (Müllerian Aplasia)

Associated Findings

Creation of a Skin Neovagina

Creation of an Intestinal Neovagina

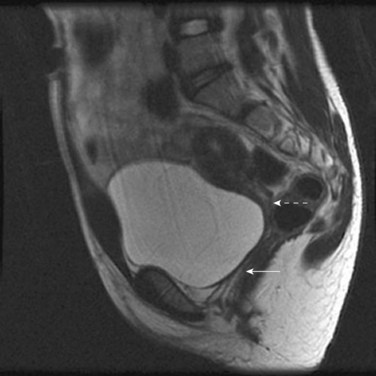

Special Considerations: Cervical Atresia

Abnormalities of Lateral Fusion

Duplication of the Uterus and Cervix with a Unilaterally Imperforate Vagina

Acquired Genital Obstructive Anomalies

Female Circumcision (Infibulation)

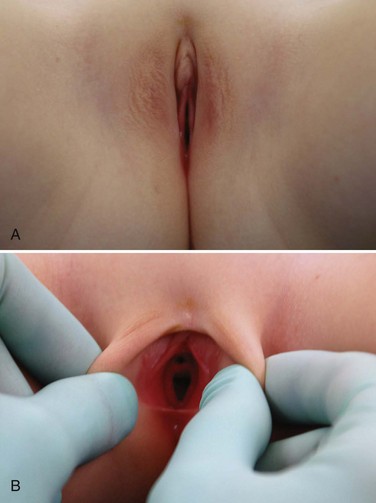

Nonobstructive Genital Anomalies (Interlabial Mass)

Specific Lesions

Labial Adhesions

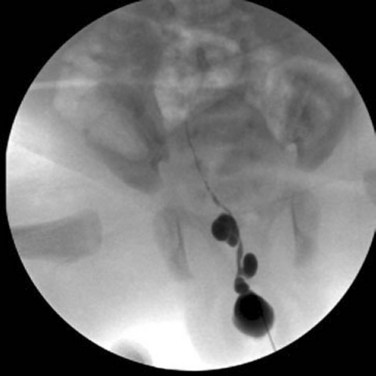

Introital Cysts

Hymenal Disorders

Prolapsed Urethra

Prolapsed Ureterocele

Urethral Polyp

Vaginal Rhabdomyosarcoma

Surgical Management of Disorders of Sexual Differentiation, Cloacal Malformation, and Other Abnormalities of the Genitalia in Girls

• Anomalies of the female reproductive system can be grouped into three main categories, those resulting from (1) hypoplasia or agenesis, (2) vertical fusion, and (3) lateral fusion.

• The McIndoe procedure (skin neovagina) is associated with a higher incidence of postoperative vaginal stenosis than a bowel neovagina.

Type IV: Excision of the entire clitoris and labia minora with nearly complete approximation of the labia majora and only a pinhole opening left near the posterior fourchette for the passage of urine and menstrual fluid (Fig. 134–13).