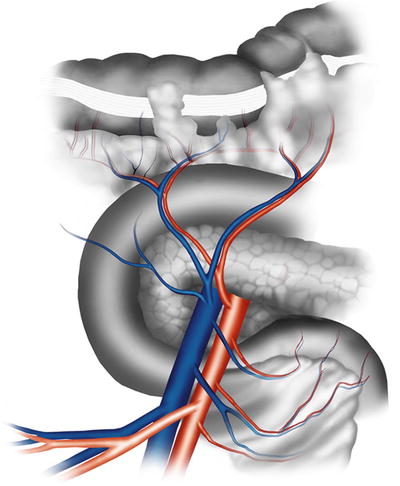

Fig. 3.1

Demonstrates relationship of ileocolic pedicle, right colon, and transverse colon. Oftentimes, the duodenum can be seen in a relatively avascular plane toward the base of the mesentery and takeoff of the ileocolic pedicle

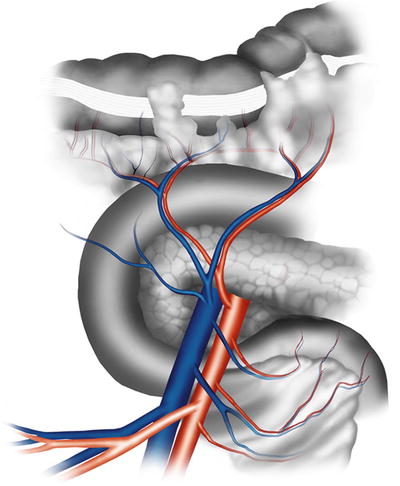

Fig. 3.2

Relationship of the ileocolic pedicle to the duodenum and right colon

A clear understanding of colon mesenteric vascular anatomy is critical in performing laparoscopic colon resections. A thorough knowledge of vascular anatomy is especially important when performing resections for colon cancer where high ligation of mesenteric vessels is required. Based on numerous anatomic, pathological, surgical, and radiologic studies, considerable variation exists in colonic vasculature (Fig. 3.3a–d). These variations need to be considered when approaching any dissection. One such example is that of the right colic artery (RCA) as a direct tributary of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) – this occurs in only 11 % of cases. Depending on the study, the RCA is a derived from branches of the ileocolic (ICA) and middle colic arteries (MCA) in up to 80-100 % of patients. Other variations include single (95 %) and double (4 %) MCA’s. When a double-MCA was found, the RCA was invariably absent. Rather than the typical SMA origin, the MCA itself can originate from either hepatic or distal splenic arteries.

Fig. 3.3 a–d

Variations in the blood supply to the right colon. With permission from Yuko Tonohira

Pearl :

When performing right colectomy, one can take advantage of the constancy of the ileocolic vessels. The ileocolic artery always courses toward the ileocecal junction (Fig. 3.1 and 3.2 ). By identifying the terminal ileum and the cecal junction and gently retracting the mesentery near the ileocolic junction anteriorly and laterally, the ileocolic vessel will be tented or “bow stringed” for easy identification. The ileocolic artery is also the first and usually the only branch of the SMA located just below the duodenal sweep. Prior to ligating the ileocolic pedicle, the duodenal sweep located just above and near the origin of the duodenal sweep must be identified in order to avoid inadvertently injuring the SMA Ileocolic pedicle (Fig. 33.4).

Fig. 3.4

Superior mesenteric artery and its branches. With permission from Yuko Tonohira

Fig. 3.5

Blood supply to the left colon

Gastrocolic Trunk

An extreme caution should be exercised when dissecting the proximal transverse colon mesentery away from the duodenum and the head of the pancreas. Henle’s gastrocolic trunk, a communicating vein between the gastroepiploic vein and the right branch of the middle colic vein or the main middle colic vein, courses behind the proximal transverse colon mesentery. Aggressive dissection in this area can tear the gastrocolic trunk, causing difficult to control hemorrhage.

The Inferior Mesenteric Artery and Its Branches

The inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) is the last branch of the aorta prior to its bifurcation into the iliac vessels. The takeoff of the IMA occurs roughly at the level of L3 vertebrae, while the bifurcation resides roughly around L4 vertebrae of the anterior aorta and slightly to the left. The IMA and its branches are the vascular supply to the hindgut structures including the distal transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon, as well as the rectum. The left colic artery is the first branch off the IMA and is typically located 2 cm from the origin of the IMA from the aorta. The distal transverse colon and descending colon are vascularized via the ascending branch of the left colic artery. The bloody supply to the distal portion of the descending colon and proximal sigmoid colon is carried by the descending branch of the left colic artery. Distally, the IMA gives off various sigmoid branches. As the IMA courses over the left common iliac artery and vein, it gives rise to its terminal branch, the superior rectal artery (Figs. 3.5 and 3.6). As its name indicates, the superior rectal artery supplies the upper rectum in addition to the distal sigmoid colon. As the vessel courses into the pelvic cavity, it splits into two branches, which descend the lateral aspects of the rectum within the mesorectum and endopelvic fascia [1, 2].

Fig. 3.6

Mobilization of the IMA. Arrows point to the direction of mobilization toward the pedicle

Fig. 3.7

Mobilization of the IMA. Arrows point to the direction of mobilization toward the pedicle. With permission from Yuko Tonohira

Pearls :

There are no arterial branches coming off the IMA posteriorly. Dissection behind the IMA gives avascular access to the retroperitoneum. Dissection in this plane is best initiated at the level of the sacral promontory where there is the greatest separation between the retroperitoneal structures and the IMA (Fig. 3.7 ).

Fig. 3.8

Variations in the blood supply to the left colon and splenic flexure (1, 2, 3 = Variations in left colic artery branches). With permission from Yuko Tonohira

In benign disease, the left colic artery can often be preserved by dividing the superior rectal artery (IMA as it crosses over the left common iliac artery), thereby maintaining collateral flow to the distal descending colon and proximal sigmoid colon. Typically, this is not a limiting factor in achieving adequate mobilization of the colon into the deep pelvis.

Splenic Flexure

The vascular anatomy distal to the middle colic artery and near the splenic flexure is variable. Connections between the left and the middle colic arteries are common. Most commonly (33 %), the ascending and descending branches of the left colic artery communicate through the marginal vessels. An additional third branch off the left colic communication with the middle colic (25 %) or the left colic artery as single arcade attached to the marginal vessels (25 %) is less frequent. In minority of cases (14.5 %), an accessory left colic artery arises from the superior mesenteric artery (Fig. 3.8).

Fig. 3.9

(a) Embryologic planes of the left colon (C colon, U ureters, G gonadal vessels, IVC inferior vena cava, A aorta). (b) In the adult, the colon has fused (green arrows) to the retroperitoneum. With permission from Yuko Tonohira

Embryologic Surgical Planes

During embryologic development, the colon starts off as a midline structure. As the embryo develops, the colon rotates laterally and fuses with the retroperitoneum. The white line of Toldt represents the lateral fusion line between the colon and the retroperitoneum (Fig. 3.9a, b). Regardless of type of dissection approach (medial to lateral vs. lateral to medial) one uses during a laparoscopic colectomy, the ultimate goal is to separate the colon and its mesentery away from the retroperitoneal structures and develop the colon as a midline structure. When performing the lateral-to-medial approach, the dissection must be started along or just medial to the white line of Toldt (Fig. 3.10a, b). Dissection in this area will allow an entry into the appropriate plane between the colon mesentery and the retroperitoneum. On the other hand, dissecting lateral to the white line will likely lead directly into the retroperitoneal space and will increase the likelihood of causing unwanted bleeding and injury to the retroperitoneal structures. When performing medial-to-lateral dissection, the mesenteric vessels are isolated and ligated before gaining an access into the retroperitoneum (Fig. 3.10a, b). Because there is no fusion plane between the colon mesentery and the retroperitoneum in the midline, closest to the named vessels, there is a tendency to veer off from the proper dissection plane (Fig. 3.11a). The surgeon has to make a conscious effort to stay within the appropriate surgical plane (Fig. 3.11b). The mantra “purple goes down” is useful to remind ourselves from getting too deep into the retroperitoneal space.

Fig. 3.10

(a) Mobilization of the left colon through the white line of Toldt (red arrow); (b) continued dissection in the correct plane leaving the gonadal vessels and ureters in the retroperitoneum. With permission from Yuko Tonohira

Fig. 3.11

(a) Continuing mobilization in the posterior plane (wrong plane) will lead to elevation and possible damage to the ureter. (b) The correct plane is above the gonadals and ureter, leaving them in the retroperitoneum. With permission from Yuko Tonohira

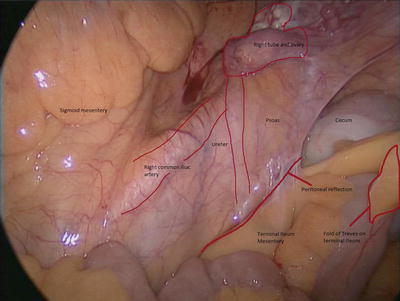

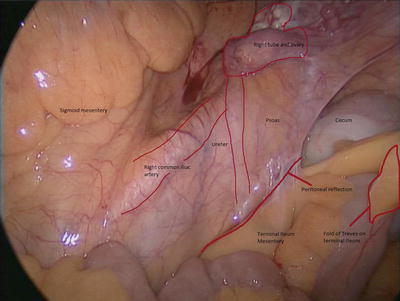

Fig. 3.12

When mobilizing the terminal ileum mesentery, care must be taken to visualize the ureter which travels over the psoas and crosses the right external iliac artery

Fig. 3.13

Course of the ureters on the psoas

The Ureter

The ureters lie under the parietal peritoneum and rest on the anterior surface of the psoas muscle (Fig. 3.12). The right and left ureters both follow a straight path from the renal pelvis to the pelvic, 4–5 cm laterally to the IVC and the aorta, respectively (Fig. 3.13). The ureters then cross over the iliac vessels to enter the pelvic brim. The right ureter classically traverses the external iliac artery (Figs. 3.16 and 3.17), whereas the left ureter lies slightly more medial and typically crosses the common iliac artery. The ureters then run posterior and inferior on the lateral pelvic sidewall. In males, the ureters continue to course medially and pass between the vas deferens (anterior) and the seminal vesicles (posterior). In females, the ureter descends posterior to the ovary and into the base of the broad ligament passing under the uterine artery. In males and females, the ureter enters the posterolateral surface of the bladder and travels at an oblique angle for approximately 2 cm until it forms the trigone [3].

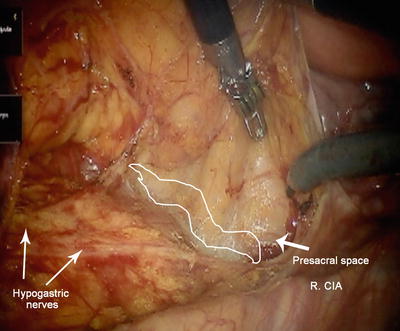

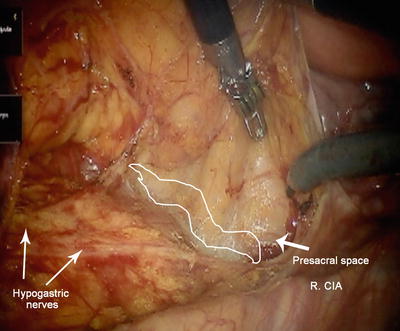

Fig. 3.14

Entry into the presacral space. Notice the course of the ureter and the nerves at this level

Fig. 3.15

The right ureter will traverse the external iliac artery, while the left ureter will cross the travel slightly more medial crossing the left common iliac vessels

Fig. 3.16

Entry into the presacral space. Notice the course of the ureter and the nerves at this level

Fig. 3.17

The right ureter will traverse the external iliac artery, while the left ureter will cross the travel slightly more medial crossing the left common iliac vessels

Fig. 3.18

Course of the ureter as it enters the pelvic sidewall and travels under the uterine artery (vas deferens) and into the bladde

In the course of performing laparoscopic right colectomy, the right ureter is typically not encountered when dissecting the right colon mesentery away from the retroperitoneal structures. Rather, the right ureter is typically visualized when the terminal ileum mesentery is sharply dissected away from the retroperitoneum over the pelvic brim (Fig. 3.19).

Fig. 3.19

Mobilization of the left colon under the IMA (green arrow depicts elevation of the pedicle and dashed arrow depicts direction of dissection). Notice the relationship of the ureter to the gonadal vessels. With permission from Yuko Tonohira

When performing a laparoscopic left colectomy or pelvic dissection, the ureters may be encountered in two locations: (1) where they cross over the common iliac vessels and (2) the lateral walls of the pouch of Douglas as they course beneath either the vas deferens or the uterine artery (Fig. 3.20). When dissecting behind the IMA into the retroperitoneal space, the left ureter is located medial to the gonadal vessels (Fig. 3.21). When developing the plane anteriorly, theoretically the ureters should not be seen at this level [4, 5].

Fig. 3.20

Dashed green line depicts the posterior rectum, while the blue and orange lines represent the middle and anterior compartments; the middle compartment is only present in females

Fig. 3.21

Pelvic anatomy highlighting the sacrum, hypogastric nerves, and avascular alveolar space between the fascia propria and presacral fascia

Pearls :

Prior to dividing the IMA pedicle, the ureter must be visualized and dissected out of harm’s way.

If the left ureter is not visualized and the psoas muscle appears bare, the plane of dissection is likely to be too deep. The left ureter and gonadal vessels may be adherent to the left colon mesentery in this case.

The Gonadal Vessels

The gonadal arteries typically arise from the anterior aorta just below the renal artery. Unlike the ureter, the gonadal vessels travel oblique toward the pelvic inlet. The gonadal arteries cross the abdominal ureters approximately halfway between the pelvic inlet and the renal pelvis. The ovarian vessels enter the broad ligament of the ovary at the pelvic brim. The testicular vessels cross the pelvic brim between the sacroiliac joint and the inguinal ligament to enter the deep inguinal ring. After traveling their respective courses, the right ovarian and testicular vein generally join the inferior cava while the left gonadal vein commonly joins the left renal vein [3].

Anatomy of the Pelvis

Low anterior (rectal) resection requires an intimate knowledge of the pelvic anatomy. Appropriate understanding of the compartments and structures within these areas permits an easier, safer, more reproducible, and oncologically sound resection.

Posterior and Lateral Compartments

The posterior compartment of the pelvis is comprised of the presacral fascia, rectum with its associated mesorectum, and surrounding fascia propria (Fig. 3.20). The presacral fascia overlies the concavity of the bony sacrum and coccyx (Figs. 3.18 and 3.23). It contains the middle sacral artery, the autonomic nerves, and the presacral veins known for causing perilous bleeding during a pelvic dissection [6, 7]. The rectum is enclosed by the fascia propria of the rectum, an investing extension of the endopelvic fascia. It encloses the mesorectum, fat, nerves, and the blood supply along the lateral extraperitoneal stalks of the rectum. The rectogenital septum marks the anterior border of the posterior pelvic compartment. The septum is clearly marked by the visceral pelvic fascia or Denonvilliers fascia that separates the extraperitoneal rectum anteriorly from the vagina (Figs. 3.24 and 3.25) or prostate and seminal vesicles [8]. Developing the plane anterior to the fascia propria or extramesorectal plane may lead to resection of Denonvilliers fascia and is associated with an increased risk of bladder and sexual dysfunction due to sacrifice of branches of the pelvic plexus of the hypogastric nerves.

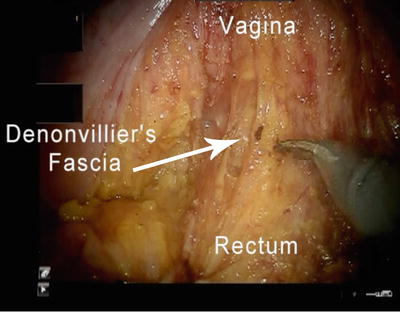

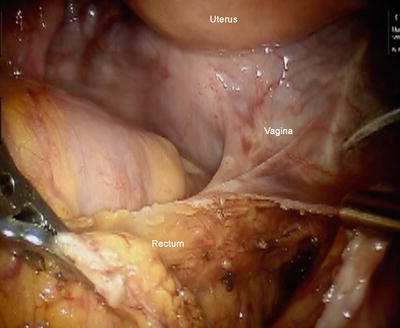

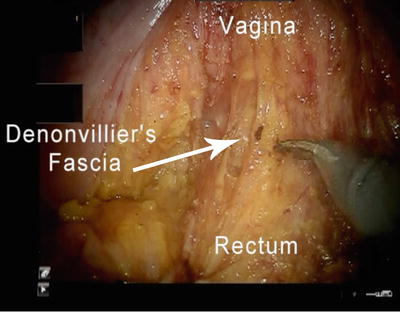

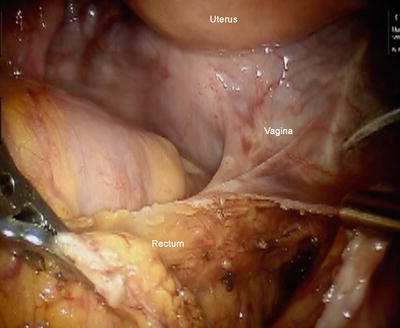

Fig. 3.22

Denonvilliers fascia can often be a difficult plane to identify; careful tension/counter-tension between the rectum and the genitourinary structure will help develop the appropriate plane

Fig. 3.23

Schematic representation of the prostate, nerves, rectum, and pelvic structures

Fig. 3.24

Reverse “C-shaped” plane during distal anterolateral dissection along the pelvic side

Fig. 3.25

Entry into the presacral space involves retraction to the left to expose the right pelvic sidewall

Pearls :

Development of Denonvilliers fascia can be difficult and is often facilitated by developing the posterior and lateral planes initially and extending them circumferentially to the anterior plane.

If done correctly, the surgeon will notice an “open C”-type or “opening-zipper” configuration of this fascia that will demarcate the appropriate dissection plane (Figs. 3.26 and 3.27 ). In this instance, starting from a known to unknown dissection will help identify the appropriate dissection plane with loose alveolar tissue as the definitive marker.

Fig. 3.26

Medial mobilization of the left colon demonstrating the arterial blood supply, ureter, and nerves

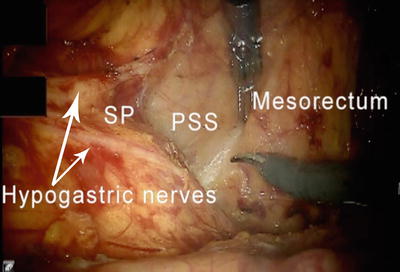

Fig. 3.27

The hypogastric plexus located just below the SP sacral promontory; PSS presacral space

Innervation

The colon and rectum are innervated by the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. The sympathetic supply of the left colon and the rectum arises from L1 to L3 and is distributed through the lumbar splanchnic nerves via the aortic and inferior mesenteric plexuses and the sacral splanchnic nerves through the superior and inferior hypogastric plexuses (Fig. 3.28). The preganglionic fibers synapse in the preaortic plexus, while postganglionic fibers travel along the IMA and superior rectal artery to the intestine. These nerves typically overlie the aorta, and care must be taken to identify and preserve these during dissection and ligation of the IMA off the aorta. The lower rectum is innervated by presacral nerves formed by the fusion of the lumbar splanchnic nerves and the aortic plexus. Subsequently, these nerves combine to form the hypogastric plexus located just below the sacral promontory (Figs. 3.29 and 3.30). The hypogastric plexus gives rise to two main hypogastric nerves which travel along the lateral sacrum and pelvic sidewalls into the pelvic plexus located in the lower rectum adjacent to what are typically conceived as the lateral stalks of the mesorectum [9, 10].