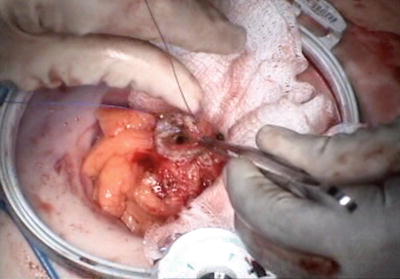

Fig. 14.1

Incarcerated rectal prolapse (Courtesy of Isaac Felemovicious, MD, with permission)

Preoperative Planning

Proper patient selection cannot be overemphasized. As with any operative procedure, patients should be medically fit and able to tolerate laparoscopy. All patients should undergo a detailed history and physical examination to include a thorough history of their bowel habits, abdominal or pelvic pain, and mucus discharge. The patient should be questioned carefully regarding the need to strain to initiate defecation, episodes of incomplete evacuation, and the use of digital maneuvers to aid in defecation. Physical examination should classically be performed in the left lateral (i.e., Sims) or squatting position, as prone jackknife may make it difficult for all but the most severe of prolapse cases. Examination should also include a digital rectal exam to assess sphincter tone, the presence of masses and concomitant pelvic floor pathology. Sphincter tone is assessed by asking the patient to actively tighten and relax the sphincter muscles. Pelvic floor muscles are assessed by asking the patient to both tighten his or her anal sphincter and “bear down” as if having a bowel movement. This simulates the action of defecation and allows for the assessment of proper contraction and relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles. The degree of prolapse is assessed by having the patient “bear down” while in the squatting or sitting position. It is important to determine if this is full-thickness prolapse with the presence of concentric rings and grooves or mucosal prolapse which has radially oriented grooves (Fig. 14.2a, b). The perineum is examined to identify increased perineal descent or bulging indicative of pelvic floor laxity. A vaginal exam on females may be appropriate to identify other concomitant anatomic abnormalities such as rectocele, cystocele, or uterine prolapse.

Fig. 14.2

(a) Full thickness rectal prolapse vs. mucosal prolapse. Notice the radial folds with (a) mucosal (hemorrhoidal) prolapse and (b) mucosal prolapse (Courtesy of Richard Billingham, MD, with permission)

Preoperative testing and imaging should be completed on a selective basis. A colonoscopy is recommended in symptomatic patients, high-risk patients, and those >50 years of age if they are not up-to-date or have not had one to rule out malignancy as the cause of prolapse. In patients with severe constipation and infrequent bowel movements, a colonic transit study may be appropriate, as the patient may benefit from a resection as well as rectopexy. In patients with pelvic floor pathology on examination or the suggestion of pelvic floor pathology by history, cinedefecography or dynamic MRI is appropriate to exclude obstructive defecation or further classify the pelvic functional disorder. Anal manometry may be utilized in patients with incontinence to determine their baseline, but this rarely will change the operative approach. Anal ultrasound is another tool available to assess sphincter integrity in patients with fecal incontinence, though again, rarely changes the procedure aimed at addressing the prolapse.

As part of the preoperative preparation, patients should undergo a mechanical bowel preparation, which may be a full preparation or enemas the morning of surgery (according to surgeon preference and patient tolerance). It is our preference to use a full preparation, to avoid having a large stool burden and straining in the early postoperative period that may increase repair failures. Preoperative intravenous anti-biotics are given at the appropriate time to ensure adequate concentration during the initial skin incision. The use of oral antibiotics can also be considered, as there are studies that show that this will aid in decreasing the luminal bacterial load [15, 16] and surgical site infections in the setting of a concomitant resection. Deep venous prophylaxis should include the use of sequential compression devices and chemical prophylaxis (i.e., heparin or low molecular weight heparin).

Procedure

Setup

Once the patient has undergone general anesthesia, a Foley catheter and orogastric tube should be placed. The patient should then be placed in a modified lithotomy position to allow adequate access to the anus and rectum. The legs should be placed into padded stirrups and ensure that padding is adequate to prevent peroneal nerve injury. Both arms should be tucked to the sides. All bony prominences should be well padded. A sacral gel-pad can also be placed to provide additional decubitus support. The patient should be secured in the operating room table in such way to allow for table movement and steep angles such as Trendelenburg that may be required for laparoscopy without significant patient movement (Fig. 14.3).

Fig. 14.3

Patient positioning in the low-lithotomy position with arms tucked, and all bony prominences padded

The operating surgeon stands on the patient’s right side with the assistant on the same or opposite side. Two monitors should be placed at the foot and left-side head of the patient (Fig. 14.4). An additional optional monitor may be placed at the head or foot on the right side for an assistant standing on the patient’s left. All equipment for both laparoscopic and open procedures should be available in the event that a conversion to open or a resection and rectopexy is to be performed (Table 14.1). If a conversion is contemplated, the surgeon and first assistant may require the use of headlights to facilitate visualization. The use of ureteral stents are not routinely necessary, but should be considered in patients with prior pelvic or lower abdominal surgery, adhesive disease, or radiation to the pelvis. While this does not prevent intraoperative injury, it does allow for timely identification and repair. The abdomen should be shaved and prepped and draped in the usual standard fashion.

Fig. 14.4

Suggested trocar and monitor placement for laparoscopic rectal prolapse repair

Table 14.1

Equipment

Head lamps for surgeon and assistant (optional) |

Laparoscopic monitors |

5- and 10 mm 30° laparoscope |

Trocars (5 mm × 3), Hasson, 10–12 mm × 1, additional 5 or 10 mm trocars for optional ports |

Laparoscopic blunt, atraumatic graspers, and scissors |

Laparoscopic needle driver |

Laparoscopic retractor (i.e., fan blade retractor, optional) |

Electrocautery with extender tip (i.e., Bovie) |

Laparoscopic energy device (surgeon preference) |

Linear cutting stapler and appropriate staple loads |

Circular cutting stapler (29–33 mm based on surgeon preference) |

Sizers for circular cutting stapler |

Nonabsorbable suture |

Prosthetic mesh (optional) |

Wound protector drape (optional for resection and extracorporeal anastomosis) |

Proctoscope |

Procedure Steps

Laparoscopic Rectopexy and Resection

Port Placement (Fig. 14.4)

Initial access: We prefer to use a Hassan port in the infra- or supraumbilical position. For patients with extensive prior resection, a Veress needle may be considered in the left upper quadrant or away from other prior surgical fields.

Establishment of pneumoperitoneum: This is achieved through the umbilical port. Following adequate pneumoperitoneum, the 10 mm 30° camera is inserted. The abdomen is explored in all four quadrants, and any abnormalities are noted.

Secondary trocar placement: An additional 10–12 mm trocar is placed in the right lower quadrant and a second 5 mm port in the right upper quadrant with emphasis on adequate triangulation. We attempt to have a minimum of a fist-size distance between each of these ports. If a rectopexy alone is the procedure, the 10–12 mm port will be changed to a 5 mm trocar.

Optional trocars: (5 mm up to 12 mm in size) may be placed in the left paramedian position, lateral to the edge of the rectus in the left mid-abdomen to assist with sigmoid retraction. Additionally, a suprapubic 5 mm port may be useful in cases where the mesh or the mesorectum is secured to the sacrum with a tacking device.

Optional hand-assist device placement: For surgeons who prefer to use a hand-assist device, this may be placed in the Pfannenstiel or midline position.

Mobilization of the Sigmoid Colon and Rectum

Mobilization of the sigmoid colon: A medial or lateral approach can be utilized depending on the comfort level and preference of the surgeon. Proximal mobilization typically involves only the section of redundant sigmoid and routine splenic flexure mobilization is not required. Further mobilization may result in more redundancy and possible recurrence of prolapse or constipation symptoms with a large “floppy” colon (see Fig. 13.4). The superior rectal/inferior mesenteric vessels should be preserved, if possible.

Lateral approach: The left colon is retracted medially with blunt atraumatic bowel graspers, utilizing gravity by tilting the operating table to the patient’s right and head down. An energy device or hook-electrocautery is then used to mobilize the sigmoid and descending colon away from left lateral abdominal wall (Fig. 14.5).

Fig. 14.5

Takedown of the lateral attachments of the sigmoid

Medial approach: The sacral promontory provides a uniform landmark to begin medial mobilization under the inferior mesenteric artery and access the avascular plane (Fig. 14.6).

Fig. 14.6

Mobilization line of dissection for a medial approach

Pearl : For either lateral or medial approach, the left ureter should be identified early and protected, typically as it courses over the bifurcation of the iliac vessels (Fig. 14.7).

Fig. 14.7

Most common location of identification of the left ureter as it crosses over the common iliac bifurcation

Rectal mobilization: The presacral space is entered at the sacral promontory, which is aided with anterior retraction on the rectosigmoid junction (Fig. 14.8). Care should be noted here to avoid transection of the hypogastric nerves that course medially in the retroperitoneum prior to forming two distinct trunks that course posteriorly and laterally in the pelvis (Figs. 14.9 and 14.10). Distally, mobilization continues down to the pelvic floor (Fig. 14.11). There are differing opinions regarding the extent of the lateral and anterior dissection.

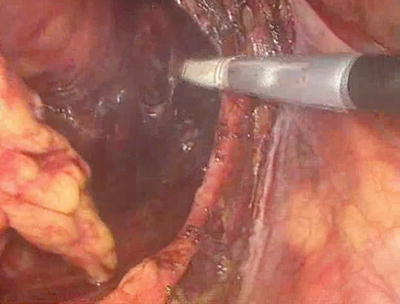

Fig. 14.8

Accessing the presacral space

Fig. 14.9

Hypogastric nerves at the level of the sacral promontory

Fig. 14.10

The right hypogastric nerve can be seen coursing posterior and into the pelvis

Fig. 14.11

Posterior extent of mobilization down to the pelvic floor past the coccyx. Note that the mesh is secured to the sacral promontory

Lateral dissection: We prefer to avoid extensive lateral dissection and do not divide the lateral stalks.

Anterior dissection: We dissect approximately 4 cm until the cut edge of the peritoneal reflection can be easily pulled back to the level of the sacral promontory (Fig. 14.12).

Fig. 14.12

Cut edge of the anterior peritoneal reflection, which should reach back to the sacral promontory to ensure appropriate mobilization prior to rectopexy

Alternative dissection: Others prefer to perform a complete rectal mobilization circumferentially down to the level of the pelvic floor.

Resection of the Redundant Sigmoid Colon

Distal division of sigmoid colon: A point is chosen for distal division past the point where the taenia splay using a cutting stapler (Fig. 14.13).

Fig. 14.13

Extent of resection for redundant sigmoid delineated. Note the limited sigmoid mobilization with proximal mobilization

Extra-corporealization of distal sigmoid colon: Once the distal portion of the bowel is transected, the bowel is brought out at either the umbilical port site or a small Pfannenstiel incision. The redundant sigmoid is delivered through the wound utilizing a wound protector (Fig. 14.14).

Fig. 14.14

The proximal transection of the sigmoid colon has completed extracorporeally with the bowel brought out through a wound protector

Proximal division of sigmoid colon: Transection of the bowel with a laparoscopic linear cutting stapler is completed at a tension-free location that easily reaches the sacral promontory without redundancy.

Placement of anvil: A purse-string suture is placed in the proximal bowel, and the anvil is secured. Sizers can then be used to determine the appropriate size of the circular stapler to be used. We almost exclusively use a 29 mm end-to-end stapler; however, sizing can be done according to surgeon preference.

Pearl: Remember that the diameter of the sizer is smaller than the corresponding stapler diameter when selecting the appropriate sized stapler .

Return of the colon to the abdomen: The descending colon can then be returned to the abdomen in preparation for anastomosis creation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree