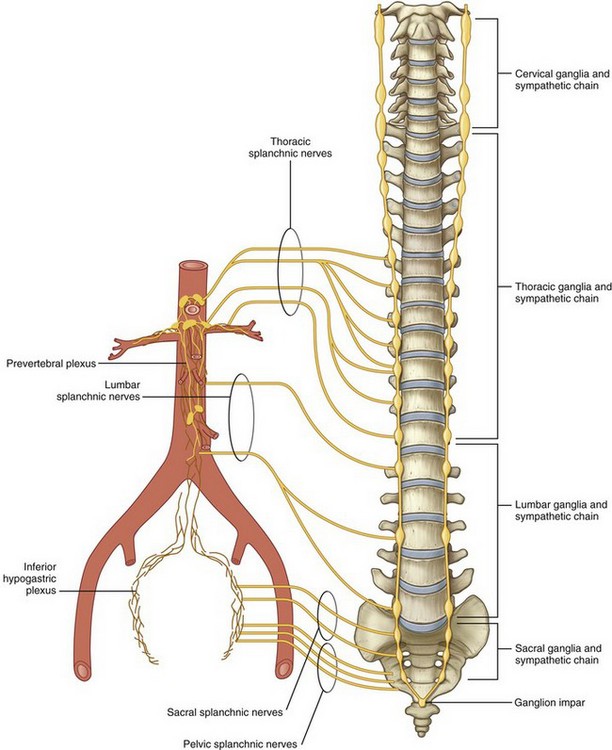

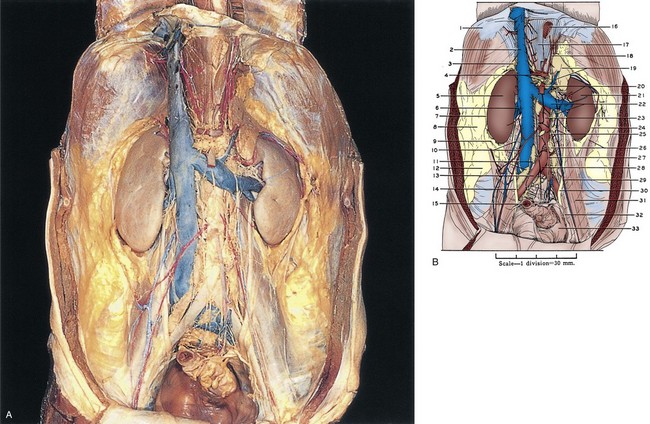

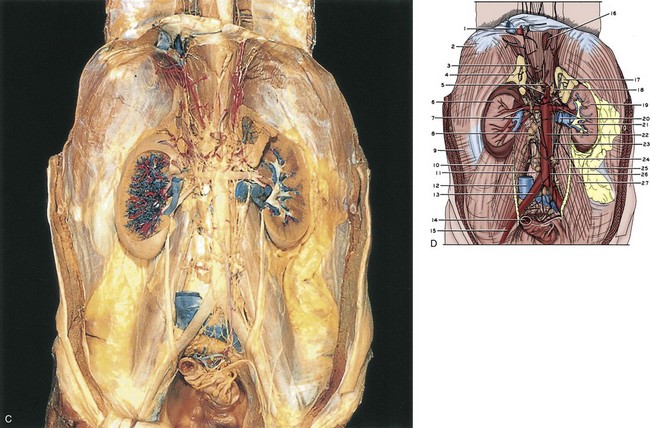

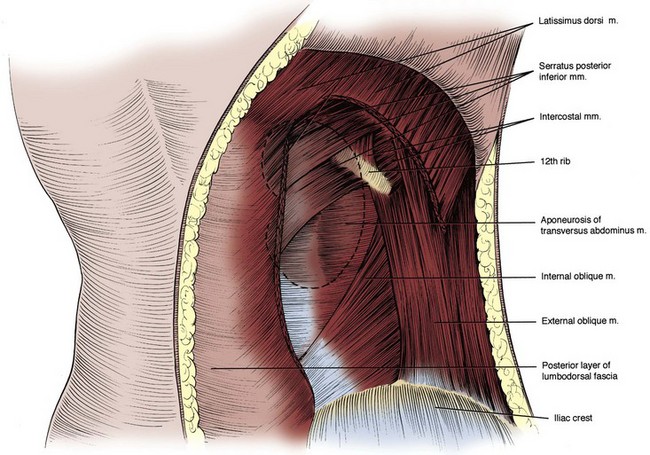

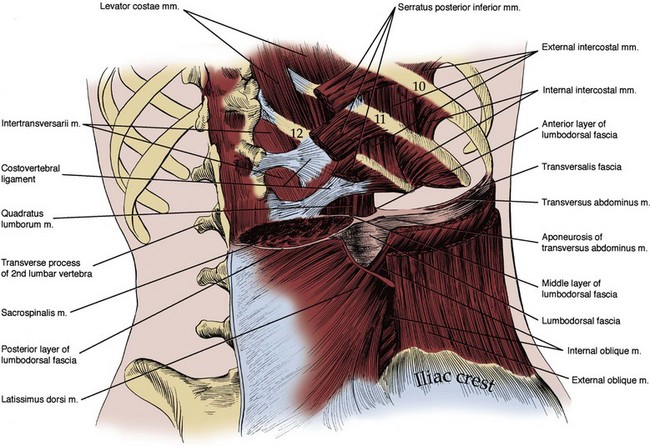

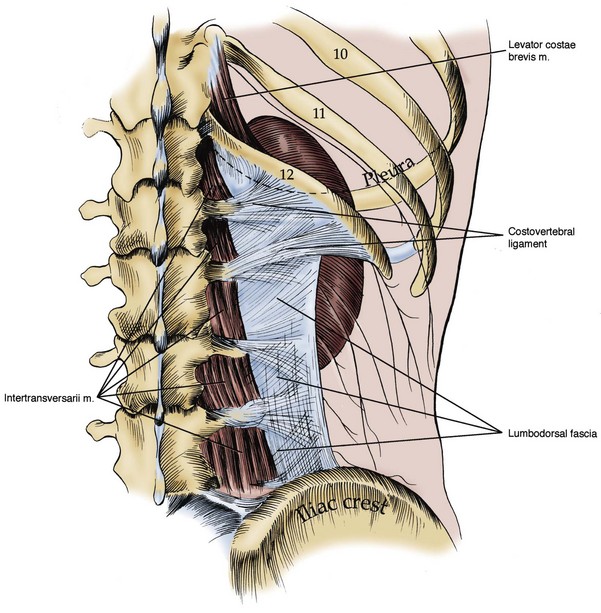

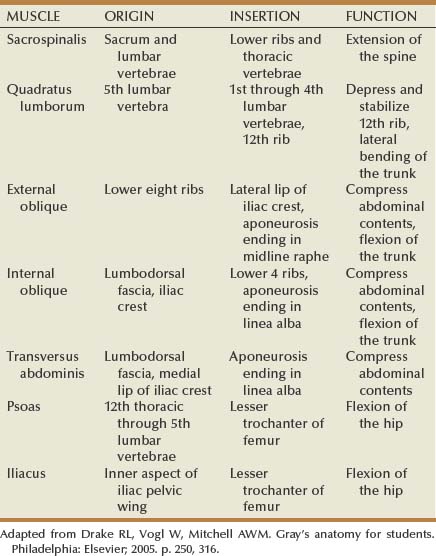

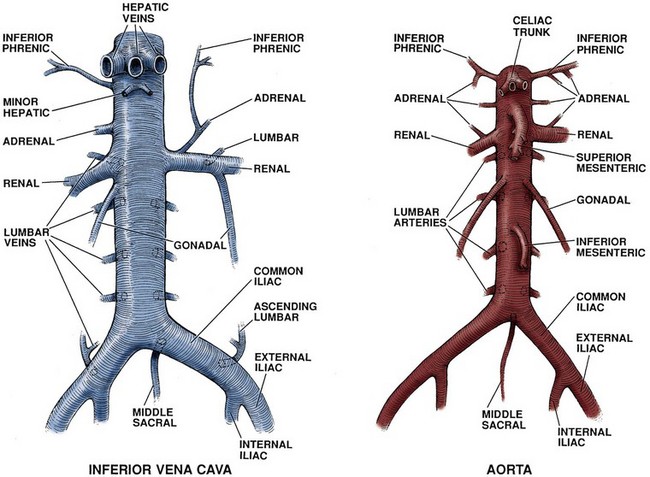

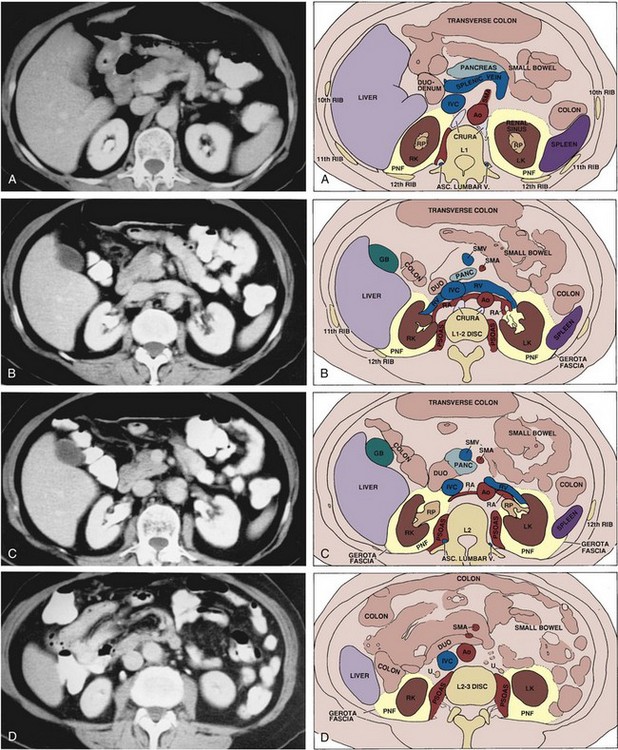

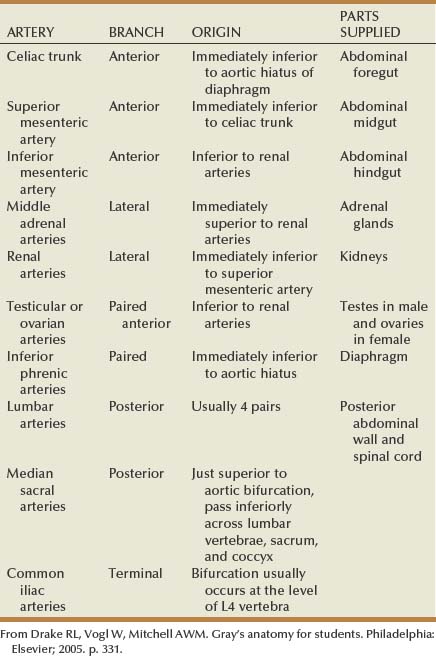

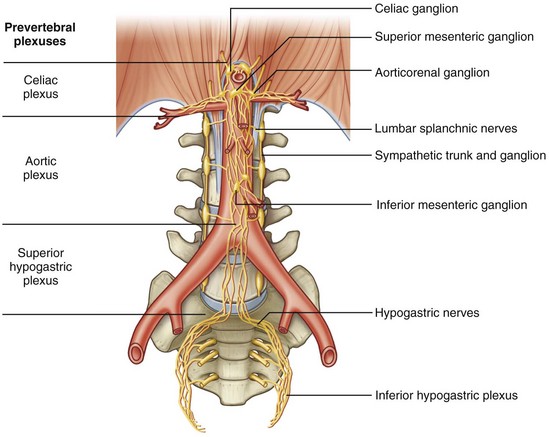

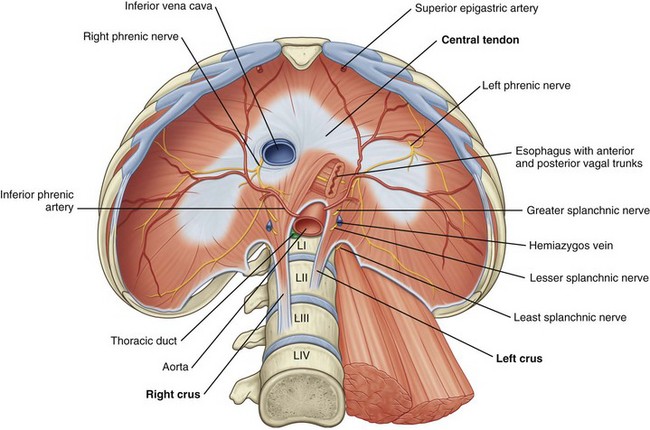

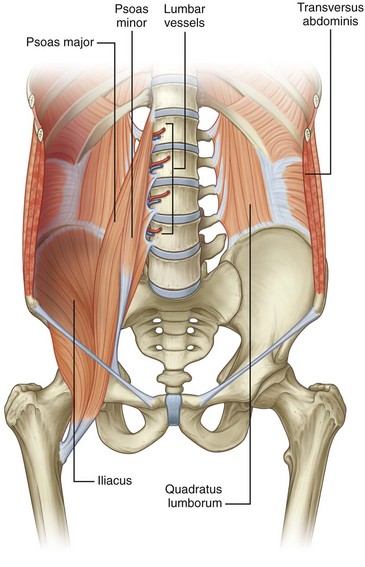

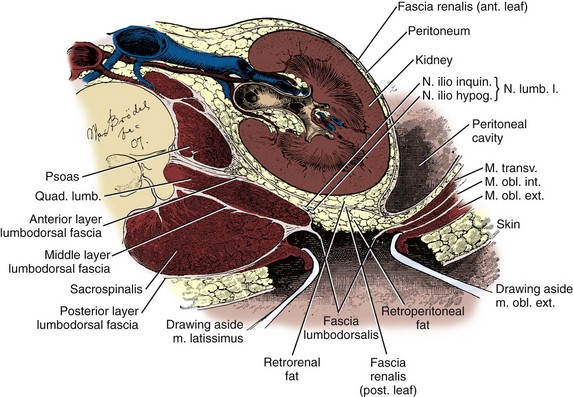

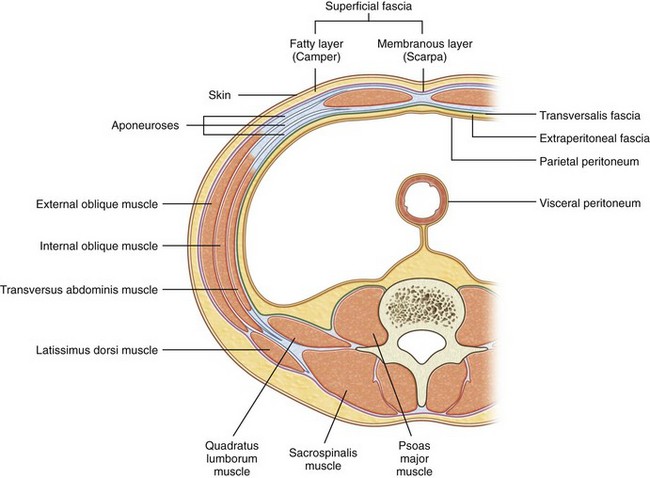

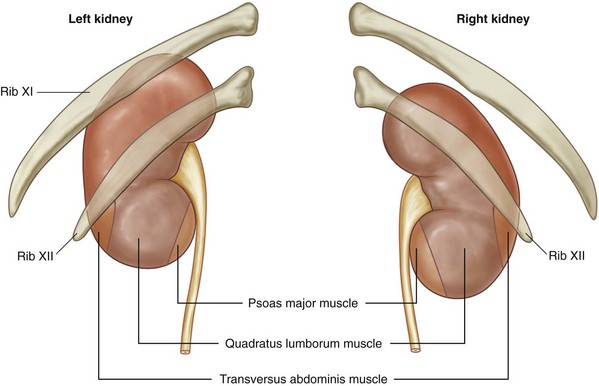

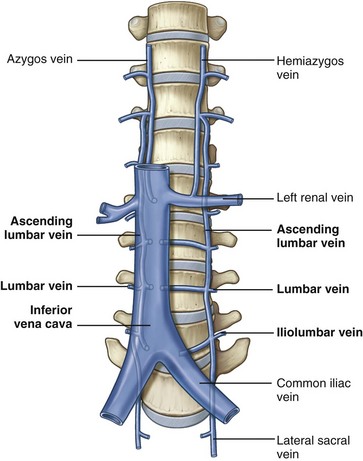

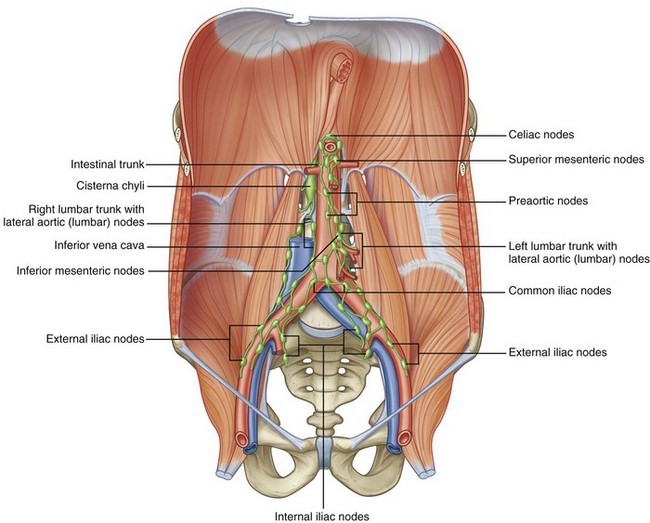

James Kyle Anderson, MD, Jeffrey A. Cadeddu, MD The retroperitoneum is bounded posteriorly by the abdominal wall, which consists of the lumbodorsal fascia and the enclosed sacrospinalis and quadratus lumborum muscles (Fig. 1–1). Laterally, the retroperitoneum is contiguous with the preperitoneal fat and is bounded laterally by the transversus abdominis musculature of the lateral abdominal wall. The peritoneum is the anterior limit, whereas cranially the diaphragm (Fig. 1–2) limits the retroperitoneum. Caudally the retroperitoneum is contiguous with the extraperitoneal pelvic structures. Figure 1–2 The diaphragm: abdominal surface. (From Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. p. 317.) See Figures 1-3 to 1-6 and Table 1–1. The lumbodorsal fascia surrounds the sacrospinalis and quadratus lumborum, which together comprise the posterior abdominal wall. The lumbodorsal fascia originates from the spinous processes of the lumbar vertebrae and extends anteriorly and cranially. As it progresses upward, it separates into three layers: posterior, middle, and anterior. Figure 1–6 Muscles of the posterior abdominal wall. (From Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. p. 316.) Key Points Retroperitoneum The quadratus lumborum and sacrospinalis muscles (see Figs. 1-6 and 1-7) form the muscular portion of the posterior abdominal wall, filling the space among the 12th rib, spine, and iliac crest. The quadratus lumborum serves a number of functions. It supports the 12th rib, thus improving diaphragmatic contraction and inspiration, as well as aiding intercostal muscle function during forced expiration. Finally, it controls lateral bending of the trunk. The sacrospinalis also controls movement of the trunk by promoting extension of the spine. These muscular and fascial relationships become important clinically when performing a dorsal lumbotomy incision. As seen in Figure 1–7, this is a vertical incision lateral to the border of the sacrospinalis and quadratus lumborum. This approach allows entrance to the retroperitoneum without violation of the musculature. (After Kelly and Burnam, from McVay C. Anson & McVay surgical anatomy. 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1984.) See Figure 1–8 and Table 1–1. Three muscular layers comprise the lateral flank musculature. From superficial to internal, these are the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles. The most superficial structure is the external oblique muscle. This muscle arises from the lower ribs and moves from lateral to medial as it progresses caudally. Final attachment is to the iliac crest caudally and the rectus sheath anteriorly. The posterior border remains free as it terminates before reaching the lumbodorsal fascia. Next is the internal oblique muscle. Again, this muscle arises from the lower rib cage, but the orientation of the fibers is from medial to lateral as they move caudally. Final attachment is to the iliac crest and lumbodorsal fascia. The final structures are the transversus abdominis muscle and transversalis fascia. The transversus abdominis muscle arises from the lumbodorsal fascia with fibers running directly transversely until it attaches anteriorly and medially onto the rectus sheath. Immediately deep to the transversus abdominis muscle is the transversalis fascia and then the retroperitoneal space. The function of the lateral flank musculature is to compress and stabilize the abdomen and trunk. This provides controlled movement and protection for the abdominal organs. Figure 1–8 Transverse section showing layers of the lateral flank musculature. (From Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. p. 252.) The psoas major muscle originates on the 12th thoracic through the 5th lumbar vertebrae (see Fig. 1–6). A smaller psoas minor is identifiable in about one half of the population and resides medial to the psoas major. The psoas muscle(s) is covered by the psoas fascia. In close proximity to the psoas muscle is the iliacus muscle, which attaches to the inner aspect of the iliac pelvic wing. As the iliacus progresses caudally it joins with the psoas muscle to form the iliopsoas muscle. This combined muscle then joins to the lesser trochanter of the femur and controls flexion of the hip. See Figure 1–9. In addition to the protection provided by the muscular layers of the posterior and lateral abdominal wall, the 10th, 11th, and 12th ribs safeguard the upper retroperitoneal space and are intimately related to the adrenal glands and kidneys. Given the close proximity, injury to these ribs can be associated with significant retroperitoneal injury. While providing protection, the lower ribs and the accompanying pleura and lung limit surgical exposure to the upper retroperitoneum. The limits of the pleura are the 8th rib anteriorly, the 10th rib in the midaxillary line, and the 12th rib posteriorly. Given this location of the pleura, flank incisions at or above the 11th or 12th ribs risk pleural violation. Figure 1–9 Structures related to the posterior surface of the kidney. (From Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. p. 322.) The abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava are the great vessels of the abdomen, providing vascular supply to the abdominal organs and lower extremities (Figs. 1-10 and 1-11). The aorta enters the abdomen via the aortic hiatus found between the diaphragmatic crura in the posterior diaphragm at the level of the 12th thoracic vertebrae (see Fig. 1–2). It continues caudally to the 4th lumbar vertebrae, where it bifurcates into the common iliac arteries. During its course through the abdomen the aorta gives off a number of large branches (Table 1–2). The paired inferior phrenic arteries are first. They supply the inferior diaphragm and the superior portion of the adrenal gland (see Fig. 1–2). Next is the celiac trunk, which is the origin for the common hepatic, left gastric, and splenic arteries that supply the liver, stomach, and spleen, respectively. The paired adrenal arteries follow with an artery going to each adrenal gland. The superior mesenteric artery leaves the aorta on the anterior side and supplies the entire small intestine and majority of the large intestine. Also of note, this artery communicates with the celiac trunk vasculature via the pancreaticoduodenal artery. Overlying the 2nd lumbar vertebrae, the paired renal arteries are the next branching point of the aorta. To the urologist, renal artery anatomy is obviously of great importance and is discussed in detail in the kidney section. The inferior vena cava (IVC) arises from the confluence of the common iliac veins at the level of the fifth lumbar vertebra (see Fig. 1–10). Because the common iliac veins lie medial and posterior to the iliac arteries, the confluence of the iliac veins is posterior and to the right of the aortic bifurcation. As the IVC progresses cranially through the abdomen, tributaries include the gonadal, renal, adrenal, and hepatic veins. In addition, the middle sacral vein enters the inferior vena cava posteriorly and the lumbar veins enter throughout the length of the abdominal vena cava. The first tributary encountered along the IVC is the middle sacral vein, which enters at the junction of the common iliac veins. Also entering along the posterior aspect of the IVC throughout its course are lumbar veins. These veins course anterior to the spinal transverse processes and generally parallel the lumber arteries. In addition to providing vascular drainage, the lumbar veins connect the IVC to the azygous venous system on the right side and hemiazygos venous system on the left side of the thorax. This provides alternate routes of venous drainage within the retroperitoneum (Fig. 1–12). Figure 1–12 Lumbar, azygos, and hemiazygos veins. (From Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. p. 332.) The next tributaries to the IVC are the gonadal veins, whose course is analogous to the gonadal arteries until approaching the IVC. During the cranial portion of their course these veins are more lateral and closer to the ipsilateral ureter. Of surgical importance is their terminal drainage because the right gonadal vein drains directly into the IVC and the left empties into the inferior aspect of the left renal vein (see Fig. 1–10). Lymphatic drainage of the lower extremities, external genitalia, testes, kidneys, and intestines is located in the retroperitoneum (Fig. 1–13). Knowledge of these lymphatic channels is useful not only for urologic oncology (e.g., testis cancer) but also for prevention of complications such as lymphocele. Drainage of the lower extremities, perineum, and external genitalia progresses through the retroperitoneum via common iliac lymph vessels and then forms ascending vertical lumbar lymphatic chains. There is flow not only cranially but also laterally, predominantly from the right to the left. Gastrointestinal lymphatic drainage also follows the vascular supply, with the majority of the lymphatics paralleling the inferior mesenteric, superior mesenteric, and celiac arteries. Eventually these lymphatics join posterior to the aorta at the level of the first or second lumbar vertebrae to form the thoracic duct. This coalescence is classically marked by a local dilation called the cisterna chyli, which tends to lie within the thorax just to the right of the aorta in a retrocrural position. Figure 1–13 Retroperitoneal lymphatics. (From Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. p. 335.) The autonomic system is further divided into sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers. The origin of these two nerve types is quite different, with the sympathetic preganglionic fibers originating from the thoracic and lumbar portions of the spinal column and the parasympathetic preganglionic fibers beginning in the cranial and sacral spinal column segments. Preganglionic sympathetic fibers enter the retroperitoneum through both the paired sympathetic chains and input from the lumbar spinal nerves (Fig. 1–14). The lumbar portion of this sympathetic chain then sends preganglionic fibers to autonomic plexuses associated with the major branches of the abdominal aorta. Within these aortic plexuses the preganglionic fibers synapse and postganglionic fibers are then distributed to the various abdominal viscera and organs. Parasympathetic input from the vagus nerve also supplies these ganglia. Figure 1–14 Sympathetic chain and splanchnic nerves. (From Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. p. 309.) In more detail, the thoracic and lumbar portions of the sympathetic chain originate from preganglionic sympathetic fibers arising from the first thoracic through the third lumbar spinal nerves (see Fig. 1–14). This chain then courses vertically along the anterolateral aspect of the spine just medial to the psoas muscle. Within the retroperitoneum, lumbar arteries and veins are closely associated with the lumbar sympathetic chain, in some instances even splitting the fibers as they cross the chain perpendicularly. From this sympathetic chain preganglionic fibers follow one of three courses. First, preganglionic fibers are sent to the various autonomic plexuses (splanchnic nerves). Once in the plexus, the preganglionic fibers synapse within a ganglion to postganglionic fibers, which in turn proceed to the abdominal viscera. Second, preganglionic fibers can synapse within the sympathetic chain ganglia and send postganglionic fibers to the body wall and lower extremities. Finally, preganglionic sympathetic fibers can proceed directly to the adrenal gland without synapsing. Within the adrenal medulla, these preganglionic fibers control release of catecholamines. The major autonomic nerve plexuses are associated with the primary branches of the aorta. These plexuses include the celiac, superior hypogastric, and inferior hypogastric plexuses (Fig. 1–15). These plexuses receive sympathetic input from the sympathetic chains via the greater, lesser, and least thoracic splanchnic nerves originating from the 5th through 12th thoracic spinal nerves. They also receive input from the lumbar portion of the sympathetic chain via the lumbar splanchnic nerves, as well as parasympathetic input via the vagus nerve.

Retroperitoneum

Posterior Abdominal Wall

Posterior Musculature and Lumbodorsal Fascia

Lateral Flank Musculature

Psoas and Iliacus Muscles

Lower Rib Cage

Great Vessels

Abdominal Aorta

Inferior Vena Cava

Lymphatics

Nervous System Structures

Autonomic System