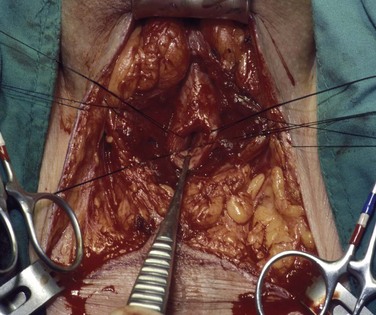

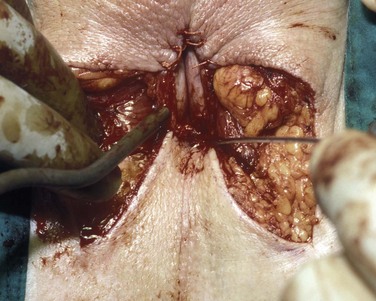

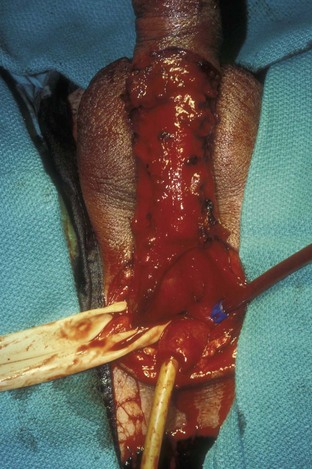

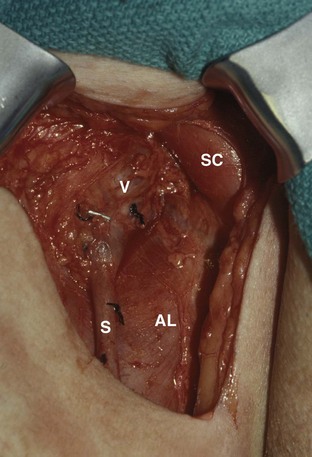

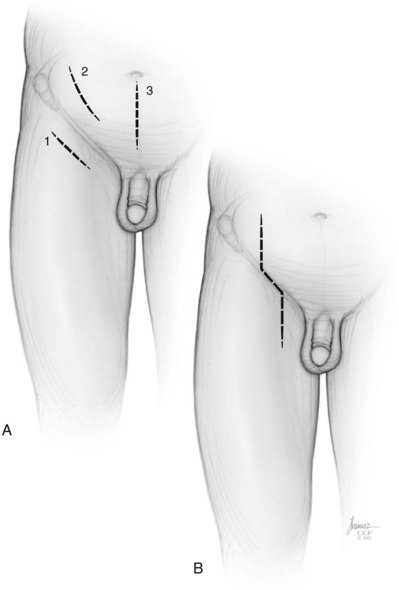

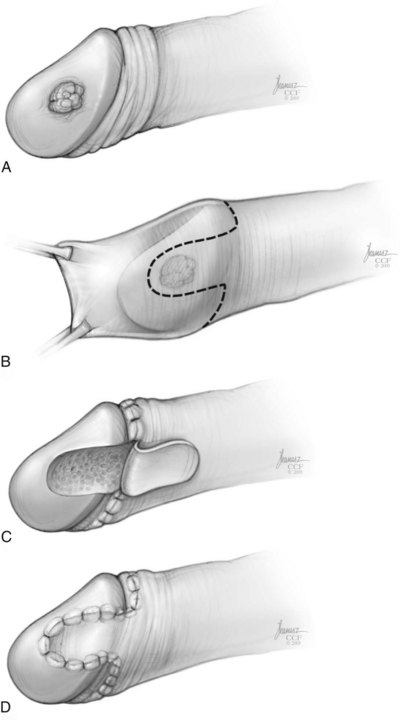

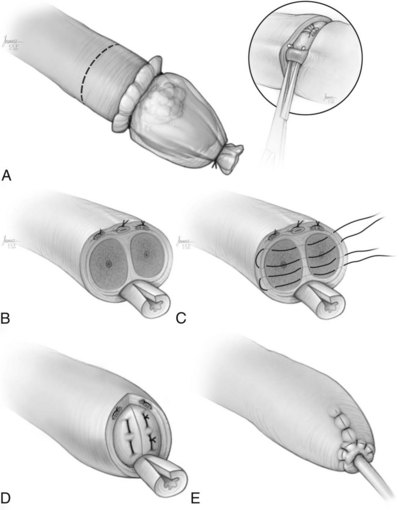

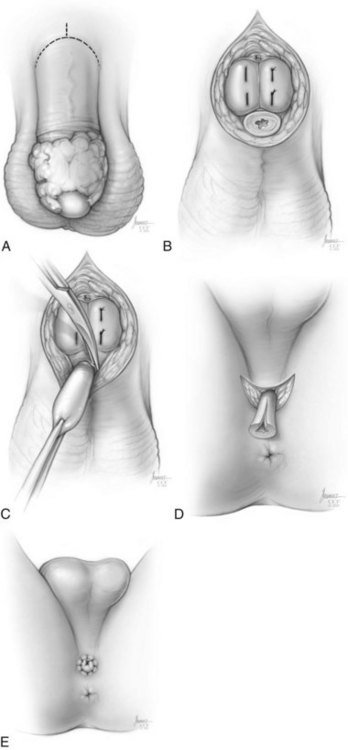

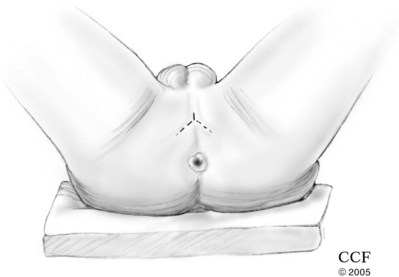

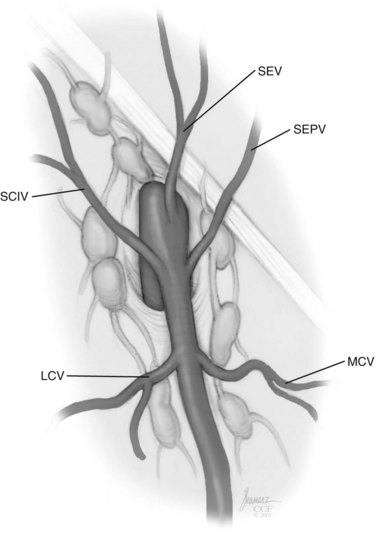

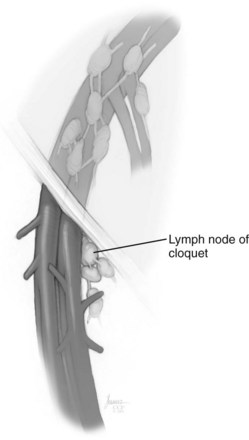

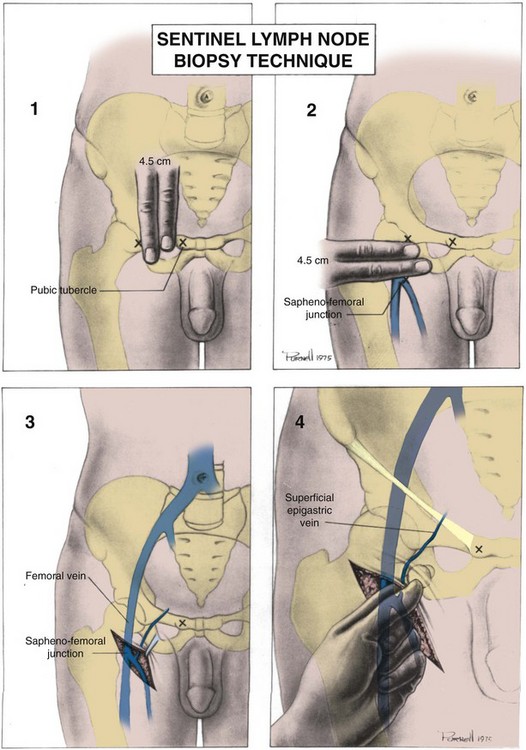

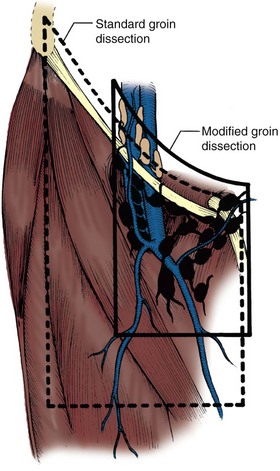

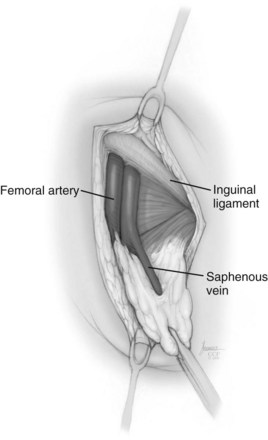

David S. Sharp, MD, Kenneth W. Angermeier, MD The majority of penile squamous cell carcinomas initially involve the glans penis, coronal sulcus, or inner preputial skin (Ekstrom and Edsmyr, 1958; Burgers et al, 1992). When a suspicious lesion is identified, a biopsy is required to provide histologic confirmation of the diagnosis. It is important to include some adjacent normal tissue with the specimen to allow optimal evaluation of the depth of invasion of the cancer. Biopsy may take the form of a punch biopsy, excisional biopsy of a relatively small tumor of the glans or foreskin, or incisional biopsy of a larger lesion that cannot be completely excised. A dorsal slit may be required to gain adequate exposure of the preputial cavity. If a lesion involves the urethral meatus, urethroscopy is indicated to evaluate the urethra, and directed biopsies are performed if any suspicious areas are noted. The CO2 laser has a wavelength of 10,600 nm. The laser energy is absorbed by intracellular water, resulting in vaporization to a skin depth of 0.01 mm. Blood vessels up to 0.5 mm in size can be coagulated. For these reasons, it has been most often used as monotherapy for treatment of dysplastic lesions and squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Greenbaum et al, 1989; Tietjen and Malek, 1998; van Bezooijen et al, 2001). It remains unclear whether the CO2 laser represents optimal therapy for carcinoma in situ; however, a local recurrence rate of up to 33% has been reported (van Bezooijen et al, 2001). Because of its cutting properties, the CO2 laser has been shown to be technically capable of excising small superficial lesions of the penis (Bandieramonte et al, 1987). In this study, surgical specimens were adequate for pathologic examination in 87% of cases, and three patients underwent a repeated laser procedure for a positive margin. The mean distance between the resected lesion and the incision borders was 0.6 mm. A similar technique was used to completely resect the entire surface of the glans penis in a series of patients with diffuse glanular disease: 3 with carcinoma in situ and 11 with superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma (Bandieramonte et al, 1988). Healing time varied from 5 to 8 weeks, and cosmetic appearance was good in all cases. Following these procedures, the authors recently reported an overall 10-year tumor recurrence rate of 17.5% for patients with stage Tis and T1 penile carcinoma. Most of the recurrences were readily treated, and the penile amputation rate was 5.5% (Bandieramonte et al, 2008). The laser most commonly reported in the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma has been the Nd : YAG laser (Rothenberger, 1986; Boon, 1988; Malloy et al, 1988; von Eschenbach et al, 1991; Horenblas et al, 1992; Frimberger et al, 2002a; Windahl and Andersson, 2003). It has a depth of penetration of 3 to 6 mm and therefore is considered to potentially be more appropriate for treating small superficial penile lesions. The application of iced saline to the treatment area during laser coagulation may prevent carbonization of the surface and promote deeper penetration of the laser energy when desired. When the Nd : YAG laser is used alone for carcinoma in situ and T1 squamous cell carcinoma, the local recurrence rate has been approximately 20% (Malloy et al, 1988; von Eschenbach et al, 1991). The Nd : YAG laser has also been used in combination with surgical excision, with the hope of improving treatment efficacy. The tumor is excised initially, followed by laser coagulation of the base and margins of the defect (Rothenberger, 1986; Boon, 1988; Horenblas et al, 1992; Windahl and Andersson, 2003). With this technique, the local recurrence has been reported to be 18% to 20%. The KTP (532-nm wavelength) laser has also been used successfully in the treatment of superficial penile carcinoma (Tietjen and Malek, 1998). It has an intermediate depth of penetration relative to the CO2 and Nd : YAG lasers, and better hemostasis than the CO2 laser. Most reports of laser therapy for penile cancer have described treatment of the lesion with a margin of 3 to 5 mm, which may underestimate the extent of the lesion in some cases. In an attempt to decrease the recurrence rate, preparation of the genital skin with 5% acetic acid has been proposed along with the use of mapping biopsies and surgical excision during the procedure (Tietjen and Malek, 1998; Frimberger et al, 2002a). The acetic acid is applied for approximately 20 minutes before the procedure, and human papillomavirus–induced areas then appear whitened. In one study, the aceto-white staining was most prominent in the periphery of the grossly visible lesions (Tietjen and Malek, 1998). Laser therapy was then carried out with elimination of all abnormal areas, with a local recurrence rate of 7% to 11%. A more recent technique intended to decrease recurrences has been described by photodynamic diagnosis with 5-aminolevulinic acid and autofluorescence to visually direct frozen-section biopsies for assessment of margin status at the time of Nd : YAG tumor ablation (Frimberger et al, 2002b). In general, laser therapy seems to be reasonable for patients with Tis and small T1 squamous cell carcinoma of the penis, and for patients with manageable T2 tumors who refuse more aggressive surgical treatment. Disadvantages include difficulty in determining the exact depth of laser coagulation; inability to treat larger lesions; and potentially difficult healing in patients who are obese, immunocompromised, or receiving anticoagulation therapy (Tietjen and Malek, 1998). Postoperative healing generally requires 8 to 12 weeks for the Nd : YAG and KTP lasers, but overall cosmetic results are generally good. Erectile function after combined CO2 and Nd : YAG laser treatment of penile squamous cell carcinoma was unaltered in 72% of patients in one study (Windahl et al, 2004). As with any form of conservative treatment, careful long-term surveillance is essential because of the remaining tissues of the preputial cavity that are at risk for carcinogenesis (Horenblas and Newling, 1993). Mohs micrographic surgery is a technique allowing removal of penile cancer by excision of tissue in thin layers (Mohs et al, 1985). This was originally described as a fixed tissue technique, but a fresh tissue technique has increasingly been used as a result of treating smaller lesions and its shorter procedural time (Brown et al, 1988; Cottel et al, 1988; Mohs et al, 1992). Color coding of the excised layers with tissue dyes allows accurate orientation of the specimen and the creation of a tissue map. Frozen sections to evaluate the surgical margin are cut horizontally from the undersurface of the tissue specimens rather than vertically, allowing microscopic examination of the entire deep and peripheral margin. Any remaining tumor is marked on the tumor map. This is continued until the lesion is completely excised. Mohs micrographic surgery allows excellent local control rates while maximizing organ preservation. Mohs reported a cure rate of 81% for tumors on the glans or prepuce. For all tumor stages, 5-year cure rates were 100% for lesions smaller than 1 cm, 83% for lesions 1 to 2 cm, 75% for lesions 2 to 3 cm, and 50% for lesions larger than 3 cm (Mohs et al, 1985). With extended follow-up, the local control rate was 94% (Mohs et al, 1992), and this has been duplicated by others (Mikhail, 1976; Brown et al, 1988). In addition to tumor size, local recurrence has been associated with advanced stage and failure of previous definitive therapy. Mohs micrographic surgery would seem to be best suited for patients with carcinoma in situ or small superficially invasive tumors, with cure rates comparable to partial penectomy. However, these results may be variable and dependent on the technique used and the experience of the surgeon (Cottel et al, 1988; Mohs et al, 1992). It should not be used in patients with higher-stage or large lesions. Complications of Mohs micrographic surgery may include meatal stenosis and glans disfigurement. Conservative surgical excision is another form of tissue-sparing therapy for low-stage penile cancer. It may be attractive in some instances when the surgeon is inexperienced regarding lasers or Mohs micrographic surgery, or when these modalities are unavailable. In addition, compared with laser therapy, excision has the advantage of providing tissue for tumor grading and assessment of margins, and it does not require the technical support necessary for Mohs micrographic surgery. Support for a conservative approach in selected patients has been provided by studies suggesting that the traditional 2-cm surgical margin may not always be necessary for cure. Pathologic analysis of 14 patients undergoing partial or total penectomy for squamous cell carcinoma revealed a mean surgical margin of approximately 14.5 mm; seven patients had a margin of 10 mm or less. No patient in this series had a local recurrence (Hoffman et al, 1999). Microscopic extent of penile carcinoma has also been shown to be dependent on tumor grade; grade 1 and grade 2 tumors demonstrated a maximum histologic extent of 5 mm in an analysis of 64 penectomy specimens (Agrawal et al, 2000). In addition, these authors were unable to identify any tumors with a pattern of discontinuous spread. The simplest form of conservative surgical excision is circumcision. Distal preputial tumors may be effectively treated in this fashion when a surgical margin of 2 cm can be achieved (Skinner et al, 1972; McDougal et al, 1986). If the cancer is more proximal and close to the coronal sulcus; however, recurrence rates may be as high as 50% (Narayana et al, 1982), and therefore excision of additional adjacent tissue is needed to ensure an adequate surgical margin. Local excision of glanular tumors is more difficult because of the requirement of a surgical margin that may not preserve enough tissue to allow an adequate remaining glans penis. This is most often done in the form of excisional biopsy of a lesion with negative surgical margins. In some cases, the surgical defect is small and can be closed primarily. If the defect is larger and primary closure is not possible, the area can be covered with an outer preputial skin flap (Ubrig et al, 2001) (Fig. 35–1). Alternatively, a full-thickness graft of penile skin or extragenital split-thickness skin graft may be used to reconstruct the area (Pietrzak et al, 2004) (Fig. 35–2). Local recurrence rates after conservative penile surgery have varied. Two early publications reported recurrence in 32% and 40% of patients (Hanash et al, 1970; McDougal et al, 1986). In 1999, Ficarra and colleagues noted local recurrence after conservative penile surgery in three of eight patients with Tis and T1 disease. More recent data have been a bit more favorable, with reported local recurrence rates of 8% to 11% (Banon Perez et al, 2000; Bissada et al, 2003; Pietrzak et al, 2004). (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2003-2010. All Rights Reserved.) Total glansectomy for penile malignant lesions was initially described in 1996 (Austoni et al, 1996). Since that time, excellent local tumor eradication has been described in a small number of patients with verrucous carcinoma and nonsquamous penile malignant neoplasms. Adequate voiding and erectile function was preserved in the majority of cases (Davis et al, 1999; Hatzichristou et al, 2001). In comparison, standard partial penectomy may be associated with significant impairment of sexual function (Opjordsmoen et al, 1994) and, in our experience, often results in the inability to void in a standing position with long-term follow-up. On the basis of this experience, a subsequent report described six patients with superficial, well to moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma limited to the glans penis who underwent glansectomy as primary therapy. With follow-up of 6 to 18 months, there were no local recurrences, and all patients maintained adequate sexual function (da Fonseca et al, 2003). The procedure begins with a distal circumferential skin incision to the level of the Buck fascia. The plane under the Buck fascia is developed proximal to the corona of the glans. Laterally, there are usually only a few small vessels within the Buck fascia that may be controlled with electrocautery. Dorsally, the neurovascular structures are divided between surgical ties. Ventrally, a plane is developed under the urethra, but it is not yet divided. Dorsal dissection is commenced in the plane between the glans penis and the tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosa, and this is continued until the glans is attached by the urethra alone. The urethra is then divided, completing the excision. Frozen-section biopsy specimens are obtained from the tips of the corpora or any other suspicious area. Reconstruction is accomplished by fixing the remaining neurovascular bundle to the tunica albuginea dorsally and the urethra ventrally if needed. The urethra is spatulated, and the penile skin is then approximated in the midline and around the neomeatus. A urethral catheter is left indwelling for 3 to 7 days. Pietrzak and colleagues (2004) have reported the results of glansectomy or glansectomy and distal corporectomy in 29 men with primarily stage T1 and T2 squamous cell carcinoma of the glans, prepuce, and coronal sulcus. Patients undergoing glansectomy had circumcision and glans excision as described before, followed by mobilization of the urethra to allow formation of a urethrostomy near the tip of the penis. Frozen-section biopsy specimens are taken from the distal tunica albuginea and the urethral margin. The shaft skin is sutured in place approximately 2 cm from the end of the penis, leaving the corporeal tips exposed. A split-thickness skin graft is harvested and quilted to the corpora, and a urethral catheter is placed. The patient is maintained at bed rest for 5 days. If the findings on frozen-section biopsy are abnormal, distal corporectomy is performed until the margins are negative, and the corpora are reconstructed as in partial penectomy. A distal split-thickness skin graft is then used to cover the corpora and to form the neoglans. Early results were encouraging; there were no local recurrences in this initial group of patients at a mean follow-up of 16 months. These data were recently updated in a review of 72 patients treated with glansectomy and split-thickness skin graft reconstruction for stage T1 and T2 tumors limited to the glans penis. Clinical efficacy was very good with two patients requiring early repeat excision for a positive surgical margin and clinical tumor recurrence, and only three late local recurrences (4%) at a mean follow-up of 27 months (Smith et al, 2007). Partial penectomy remains the most common surgical procedure for treatment of the primary tumor in patients with invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Successful local control is accomplished in the majority of patients by amputation of the penis at least 2 cm proximal to the tumor. Additional goals of the procedure are to preserve the ability to void in a standing position and possibly to allow sexual function. The lesion is initially excluded from the surgical field by a small towel or surgical glove (Fig. 35–3). Some authors have recommended the use of a tourniquet at the base of the penis, but we have not found this to be necessary. The skin and underlying dartos fascia at the proposed line of amputation are incised circumferentially to the level of the Buck fascia. The Buck fascia is incised laterally, and a plane is dissected between the tunica albuginea and the neurovascular structures dorsally. The dorsal penile vessels are sequentially ligated and divided. The corpora cavernosa are sharply divided, leaving the specimen attached only by the urethra. The urethra is dissected for a distance of 1 to 1.5 cm distal to the proximal corpora and then transected. The corpora are closed transversely with interrupted horizontal mattress sutures of 2-0 polydioxanone. The penile skin is closed in the midline over the corporeal ends with interrupted 3-0 or 4-0 chromic suture material. A ventral urethrostomy is constructed by approximating the urethra to the adjacent penile skin with interrupted 4-0 chromic sutures (Fig. 35–4). An indwelling urethral catheter is left in place for 3 to 5 days. If additional stump length is needed to increase the probability of adequate voiding function, the suspensory ligament of the penis may be divided. The proximal corpora may subsequently be dissected off of the pubic arch for a short distance as well. Scrotal flaps are used to help with skin coverage as needed, and the skin is attached to the pubic arch to preserve the dissected penile length. Division of the penoscrotal fold with a Z-plasty at the penoscrotal junction ventrally may contribute to better definition of the remaining penile stump (Parkash et al, 1986). In selected patients, glans reconstruction may be considered by covering the distal corpora with a split-thickness skin graft (de Souza, 1976) or a two-stage pedicled flap of scrotal skin (Mazza and Cheliz, 2001). (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2003-2010. All Rights Reserved.) The reported local recurrence rate after partial or total penectomy has ranged from 0% to 8% (Hardner et al, 1972; de Kernion et al, 1973; McDougal et al, 1986; Horenblas et al, 1992). Two studies have suggested that recurrence rates are dependent on tumor stage, reporting a recurrence rate of 0% for patients with T1 tumors and 18% to 21% for T2 lesions (Lindegaard et al, 1996; Brkovic et al, 1997). Although one of the accepted goals of partial penectomy is to allow upright voiding, the percentage of patients able to do this after surgery has not been well documented. A 6% incidence of urethral meatal stenosis has been reported (Horenblas et al, 1992). In our experience, a significant number of men sit to void in the long term because of spraying of the urinary stream. In terms of sexual function, most published reports have indicated that approximately 20% of patients describe adequate sexual function postoperatively (Opjordsmoen et al, 1994; Ficarra et al, 1999; Mazza and Cheliz, 2001). Total penectomy is a bit of a misnomer, because the penis is amputated at or near the level of the suspensory ligament of the penis without removal of the corpora cavernosa more proximally. It is indicated for penile tumors whose size or location would not allow excision with an adequate surgical margin and preservation of a remnant sufficient for upright voiding. The primary tumor is draped and an elliptical incision made around the base of the penis (Fig. 35–5). Dissection is commenced in the plane between the tunica albuginea and Buck fascia dorsolaterally, and the dorsal vessels are ligated and divided. The corporeal bodies are sharply transected, and the urethra is divided at the same level. The corpora are then closed with interrupted horizontal mattress sutures of 2-0 polydioxanone. (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2003-2010. All Rights Reserved.) A perineal urethrostomy is then constructed by one of two techniques. The most commonly described method is to mobilize the urethra from the surrounding bulbospongiosus muscle and dorsally from the corporeal bodies to near the departure of the urethra from the bulb (Fig. 35–6). A small U-shaped incision is made in the perineum. The mobilized urethra is transposed through the perineal opening without angulation. The urethra is spatulated dorsally, and the skin is sutured to the full-thickness urethra with 3-0 polyglactin sutures. Alternatively, a flap inlay urethrostomy may be constructed without mobilization of the urethra. A modified lambda incision, with a short vertical limb, is made in the perineum (Fig. 35–7). The soft tissues overlying the urethra are incised, and the bulbospongiosus muscle is divided in the midline to expose the corpus spongiosum of the bulbous urethra. A 3- to 4-cm ventral urethrotomy incision is made and carried proximally to a point just distal to the bulbomembranous junction (Fig. 35–8). The lateral aspects of the corpus spongiosum in the region of the urethrotomy are fixed to the adjacent corporeal bodies with a few interrupted sutures of 4-0 polydioxanone to splay the opened urethra. The perineal skin flap is sutured to the full-thickness urethra with 3-0 polyglactin starting in the midline and working laterally as far as the flap will easily reach (Fig. 35–9). The urethrostomy is completed by approximation of the scrotal skin to the urethra dorsolaterally, and the resulting short lateral skin incisions are closed in standard fashion (Fig. 35–10). Figure 35–7 Incision for flap perineal urethrostomy. (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2003-2010. All Rights Reserved.) Although it is not commonly done, radical penectomy with excision of the corporeal bodies in their entirety may on occasion be necessary. We have had experience with this procedure in three patients, one with epithelioid sarcoma of the penis involving multiple sites within the corpora cavernosa (Ormsby et al, 2000), and for palliation in two patients with extensive metastatic disease within the corporeal bodies related to transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder and adenocarcinoma of the rectum. The patient is placed into lithotomy position with adjustable stirrups so that the level of the legs can be altered during the procedure as needed. The procedure begins with a peripenile incision as for total penectomy, and the corpora are mobilized off of the ischiopubic rami proximally to the point at which the dorsal vein may be seen coursing under the pubis, where it is ligated and divided (Fig. 35–11). A modified lambda incision is then made in the perineum, and the penis is maneuvered through this incision (Fig. 35–12). Dissection of the corporeal bodies continues to the tips of the crura, which are completely excised. Suture ligatures are used to control the dorsal penile and cavernosal vasculature near the dorsal aspect of the crura, and in the penile hilum. A plane is developed between the proximal urethra and the corpora, and the urethra is then transected, leaving 2 to 3 cm of urethra to form a perineal urethrostomy (Fig. 35–13). A standard flap perineal urethrostomy is then constructed. A small suction drain is placed, and the peripenile incision is closed transversely. Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis spreads initially to regional lymph nodes before the occurrence of distant metastatic disease. Lymphatic spread occurs in a systematic fashion along the normal route of penile lymphatic drainage. Lymphatic vessels draining the prepuce and skin of the penile shaft converge dorsally and then divide at the base of the penis to drain into the right and left superficial inguinal nodes. Drainage from the glans penis is toward the frenulum, where large trunks are formed and encircle the corona to unite with those from the other side on the dorsum. They traverse the penis to the base within the Buck fascia, draining through presymphyseal lymphatics into the superficial inguinal nodes and the deep inguinal nodes of the femoral triangle. It is not uncommon for the tumor to metastasize to the contralateral inguinal nodes. Drainage proceeds from the inguinal nodes to the ipsilateral pelvic lymph nodes. Although some anatomic texts have stated that penile lymphatics may drain directly to the external iliac nodes, we are not aware of any patients or reports in the literature in which this has occurred clinically. Although penile carcinoma metastatic to the inguinal lymph nodes confers a poorer prognosis overall, aggressive lymphadenectomy is associated with improved long-term survival and potential cure in 30% to 60% of patients (McDougal et al, 1986; Horenblas and van Tinteren, 1994). In addition, immediate resection of clinically occult lymph node metastases is associated with improved survival when compared with delayed resection of involved nodes at the time of clinical detection (Kroon et al, 2005). If the tumor has spread to the pelvic nodes, long-term survival is less than 10%. See Figs. 35-14 and 35-15 on the Expert Consult website The inguinal lymph nodes are divided into superficial and deep groups, which are anatomically separated by the fascia lata of the thigh. The superficial group is composed of 4 to 25 lymph nodes that are situated in the deep membranous layer of the superficial fascia of the thigh (Camper fascia). The superficial inguinal nodes have been divided into five anatomic groups (Daseler et al, 1948): (1) central nodes around the saphenofemoral junction, (2) superolateral nodes around the superficial circumflex vein, (3) inferolateral nodes around the lateral femoral cutaneous and superficial circumflex veins, (4) superomedial nodes around the superficial external pudendal and superficial epigastric veins, and (5) inferomedial nodes around the greater saphenous vein (Fig. 35–14). The deep inguinal nodes are fewer and lie primarily medial to the femoral vein in the femoral canal. The node of Cloquet is the most cephalad of this deep group and is situated between the femoral vein and the lacunar ligament (Fig. 35–15). The external iliac lymph nodes receive drainage from the deep inguinal, obturator, and hypogastric groups. In turn, drainage progresses to the common iliac and para-aortic nodes. (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2003-2010. All Rights Reserved.) Figure 35–15 Deep inguinal lymph nodes. (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2003-2010. All Rights Reserved.) The concept of sentinel node biopsy in patients with invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis and clinically negative inguinal regions was proposed by Cabanas (1977) after extensive study of lymphangiograms and anatomic dissections. The impetus for a conservative approach to evaluate this group of patients arose from the realization that surgical treatment of inguinal metastases is desirable, and because of the significant morbidity associated with conventional inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. A 5-cm incision is made parallel to the inguinal crease and centered two fingerbreadths lateral and inferior to the pubic tubercle. By insertion of the finger under the upper flap toward the pubic tubercle, the sentinel lymph node is encountered and excised (Fig. 35–16). Although Cabanas reported 90% survival in patients with normal findings on sentinel node biopsy, subsequent authors found the results to be less satisfactory, with reports of development of extensive regional metastases after a biopsy with normal findings (Perinetti et al, 1980; Wespes et al, 1986). As an alternative, Pettaway and colleagues (1995) evaluated extended sentinel node biopsy, during which all of the lymph nodes between the inguinal ligament and the superficial external pudendal vein were removed. This approach has also been abandoned, because it resulted in a false-negative rate of 15% to 25% (Ravi, 1993; Pettaway et al, 1995). Figure 35–16 Sentinel lymph node biopsy technique as described by Cabanas. (From Cabanas RM. An approach for the treatment of penile carcinoma. Cancer 1977;39:456–66.) Efforts have been made to improve the accuracy of sentinel node biopsy. Dynamic sentinel node biopsy with lymphoscintigraphic imaging has been described on the basis of experience in other tumors (Horenblas et al, 2000). The technique starts the day before surgery with the intradermal injection of technetium Tc 99m nanocolloid at three or four sites around the primary tumor. Dynamic anterior lymphoscintigraphy is subsequently performed at defined intervals. The location of the sentinel node is marked on the skin. Shortly before surgery, 1 mL of patent blue dye is injected around the tumor in a similar fashion. The sentinel node is harvested after dissection of blue lymphatic vessels and intraoperative detection of radioactivity by use of a gamma-ray detection probe. Detection of positive nodes has also been aided by preoperative inguinal ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration of any abnormal-appearing lymph nodes. A false-negative rate of 18% was initially reported with this approach (Kroon et al, 2004). More recently, the authors have amended their algorithm with the addition of routine inguinal exploration in the absence of radiotracer visualization, intraoperative palpation of the wound for abnormal nodes, and extended pathologic analysis of excised nodes as means of decreasing the number of false-negative biopsy results. These additional maneuvers have decreased the false-negative rate to 5% while maintaining a low risk of complications (Leijte et al, 2007). In 1988, Catalona proposed a technique of modified inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy designed to provide staging information and therapeutic benefit similar to standard extended lymphadenectomy with less morbidity (Fig. 35–17). Key aspects of the procedure are (1) shorter skin incision, (2) limitation of the dissection by excluding the area lateral to the femoral artery and caudal to the fossa ovalis, (3) preservation of the saphenous vein, and (4) elimination of the need to transpose the sartorius muscle. All of the superficial lymph nodes within the described area are removed, as are the deep inguinal nodes that are located primarily medial to the femoral vein to the level of the inguinal ligament. Figure 35–17 Limits of standard and modified groin dissection. (From Colberg JW, Andriole GL, Catalona WJ. Long-term follow-up of men undergoing modified inguinal lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the penis. Br J Urol 1997;79:54–7.) The procedure begins by placing the patient into a frog-legged position. A 10-cm skin incision is made approximately 1.5 to 2 cm below the inguinal crease. Skin flaps are developed in the plane just beneath the Scarpa fascia for a distance of 8 cm superiorly and 6 cm inferiorly. The superior dissection is carried to the level of the external oblique fascia with exposure of the spermatic cord. A funiculus of lymphofatty tissue, extending from the base of the penis to the superomedial portion of the lymph node packet, is ligated and divided. Dissection commences in a caudad direction with removal of the superficial and deep inguinal nodes, with the boundaries consisting of the adductor longus muscle medially and the femoral artery laterally. The saphenous vein is identified and preserved, although a number of branches draining into it will need to be sacrificed. The nodal packet is dissected caudad to the level of the skin flap dissection (Fig. 35–18), at which point the lymphatics are carefully ligated and the specimen is delivered from the operative field (Fig. 35–19). A closed-suction drain is placed, and the incision is closed in standard fashion. (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2003-2010. All Rights Reserved.) Morbidity after modified inguinal lymphadenectomy consists primarily of minor complications including seroma (25% to 27%), lymphorrhea (9% to 10%), and wound infection or skin necrosis (0% to 9%). These have been self-limited in the majority of cases (Parra, 1996; Coblentz and Theodorescu, 2002; Jacobellis, 2003; Bouchot et al, 2004; d’Ancona et al, 2004). Temporary lower extremity edema has been reported in approximately 20% of patients, and persistent edema is uncommon. Major complications are rare. Although it is not universally accepted, the literature suggests that the primary use of modified inguinal lymphadenectomy currently is in patients with a primary tumor that places them at increased risk for inguinal metastasis and clinically negative groins on examination (stage T2 or greater, presence of vascular/lymphatic invasion, or high grade). If nodal metastasis is detected on frozen-section examination of the specimen, the procedure is converted to a standard extended lymphadenectomy. The false-negative rate for this procedure, in terms of detecting inguinal metastatic disease, ranges from 0% to 5.5% in the majority of published reports (Parra, 1996; Colberg et al, 1997; Coblentz and Theodorescu, 2002; Bouchot et al, 2004; d’Ancona et al, 2004). Radical ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy is indicated in patients with resectable metastatic adenopathy and may be curative when the disease is limited to the inguinal nodes. We have also favored its use as a palliative procedure in patients with documented inguinal metastasis who are fit for surgery. If left unchecked, cancer-bearing inguinal nodes may lead to significant complications, such as infection or abscess with chronic foul-smelling drainage or life-threatening femoral hemorrhage (Fig. 35–20). The procedure is carried out 4 to 6 weeks after surgical treatment of the primary tumor. Antibiotics are administered during this time to reduce the inflammatory component of the regional adenopathy. The patient is positioned with the involved thigh slightly abducted and externally rotated with cushioned support under the flexed knee. The inguinofemoral dissection is designed to cover an area outlined superiorly by a line drawn from the superior margin of the external ring to the anterior superior iliac spine, laterally by a line drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine extending 20 cm inferiorly, and medially by a line drawn from the pubic tubercle 15 cm down the medial thigh. In most situations, the procedure is carried out through an oblique incision approximately 3 cm below and parallel to the inguinal ligament and extending from the lateral to the medial limit of the dissection (Fig. 35–21). If an area of the skin overlying the cancer-bearing nodes is invaded or adherent and requires excision, an elliptical incision is made around the involved skin and then extended medially and laterally. In this setting, the incision may alternatively be extended superiorly from the lateral border of the ellipse and inferiorly from the medial border to make a single S-shaped incision for the iliac and inguinofemoral dissections (Fig. 35–22).

Penile Cancer

Primary Tumor

Penile Biopsy

Laser Therapy

Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Conservative Surgical Excision

Partial Penectomy

Total Penectomy

Radical Penectomy

Regional Lymph Nodes

Inguinal Anatomy

![]() .

.

Sentinel Node Biopsy

Modified Inguinal Lymphadenectomy

Radical Ilioinguinal Lymphadenectomy