Chapter 18 Stone Extraction

Following endoscopic sphincterotomy, the majority of stones less than 1 cm in diameter will pass spontaneously.1 Nonetheless, it is current practice to attempt stone extraction and clear the bile duct to avoid subsequent stone impaction and the risk of cholangitis. Extraction of stones is most commonly achieved using a balloon catheter or wire basket. However, large stones—particularly those greater than 2 cm in diameter—are difficult to remove and will require some form of stone fragmentation prior to removal with baskets or balloons. The most popular method of stone fragmentation is mechanical lithotripsy using large and strong baskets to break up the stone. Other methods include intraductal electrohydraulic or laser lithotripsy and, rarely, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL). In cases in which endoscopic stone extraction fails, surgery or chemical dissolution of the stone is an option,2–5 though in most units additional endoscopic attempts (sometimes multiple) are undertaken, which often allow complete stone clearance. Temporary stenting provides decompression and is effective in controlling biliary sepsis. Leaving the stent in place combined with administration of oral dissolution agents reduces stone size and facilitates endoscopic removal.6–8 Alternatively, permanent stenting can be used for biliary drainage in cases of large nonextractable stones to prevent cholangitis.9–14

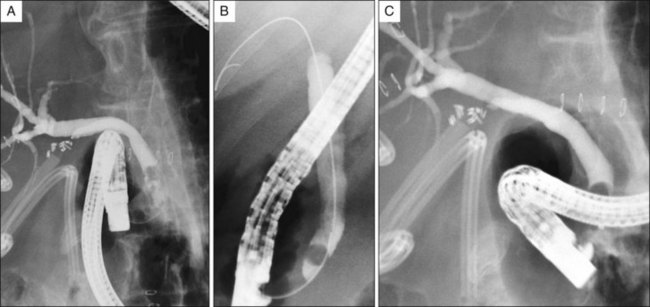

In the setting of suspected choledocholithiasis we suggest that initial contrast injection be performed using 60% (normal strength) contrast and early filling images be carefully analyzed to detect stones, which are seen as filling defects, often with a meniscus sign. However, if the bile duct is dilated in caliber, diluted contrast should be used to avoid masking smaller stones within a large amount of dense contrast.15 To avoid missing stones hidden behind the endoscope, the endoscope can be advanced into the long position to expose the stone (Fig. 18.1). In patients with suspected intrahepatic stones or stones above a stricture, an occlusion cholangiogram with the balloon inflated above the cystic duct takeoff may be necessary in order to visualize the stones. Keep in mind that injection of excess contrast into an obstructed, infected system may cause a rise in intrabiliary pressure that may result in worsening cholangitis or inducing sepsis.

Dilation of a downstream biliary stricture (see Chapter 40) may be necessary to remove stones that occur proximally in the biliary tree. Stricture dilation can be achieved using hydrostatic balloons.16 These balloons C are available in different sizes ranging from 4 to 10 mm in diameter and can be placed over a guidewire across the stricture. Larger diameter nonbiliary over-the-wire balloons (pyloric and colonic) can also be used. Dilute contrast is used to inflate the balloon to a predetermined pressure as recommended by the manufacturer. The balloon has radiopaque markers that help to position the balloon across the stricture. The choice of the balloon size should be based on the diameter of the normal portion of the bile duct to avoid unnecessary damage to the bile duct. The balloon is inflated to the recommended pressure and the persistence or disappearance of the waist on the balloon is noted. This will determine the effectiveness of the dilation and ease of subsequent stone extraction through the stricture. If the stricture cannot be dilated adequately, stone fragmentation is necessary prior to removal. Alternatively, one or more plastic biliary stents or a covered, removable metal stent can be placed to allow subsequent stent and stone extraction.17 Balloon dilation or sphincteroplasty after an initial small sphincterotomy has been used to facilitate removal of a large stone while avoiding the risks of bleeding and perforation from a large sphincterotomy (see Chapter 17).18

Indications and Contraindications

Indications

1. Impacted ampullary stone. Such patients present with biliary pancreatitis and/or cholangitis. In general, an impacted ampullary stone precludes easy deep biliary cannulation and sphincterotomy, making stone extraction difficult without precut sphincterotomy.

2. Common bile duct stones. Patients usually present with abdominal pain or abnormal liver function tests with or without cholangitis. In some asymptomatic patients bile duct stones are diagnosed by imaging studies performed for unrelated reasons. It is believed that the risk of complications of untreated stones is greater than the risk of AEs that occur with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and stone removal.

3. Intrahepatic duct stones. Patients are at risk for development of cholangitis.

4. Failure of standard balloon or basket extraction. When stones are too large to be removed with standard balloons or wire baskets, mechanical lithotripsy, large-diameter papillary balloon dilation, or intraductal lithotripsy is indicated for stone fragmentation prior to removal.

5. Impacted stone retrieval basket containing a stone. Mechanical lithotripsy, balloon dilation, and other techniques can be used to free the basket by fragmenting the stone.

6. Failed mechanical lithotripsy. When mechanical lithotripsy fails to allow stone removal, particularly large stones that are difficult to capture with the lithotripsy basket, or an impacted stone, intraductal electrohydraulic lithotripsy is an effective option. Alternatively, biliary stent placement with a repeat attempt at endoscopic extraction can be undertaken.

Description of Technique

Removal of an Impacted Ampullary Stone

Attempts should be made to disimpact the stone proximally within the bile duct in order to achieve deep cannulation. This is achieved by advancing a sphincterotome preloaded with a guidewire alongside the stone. However, it may be necessary to use a needle knife to cut directly into the bulging papilla caused by the impacted stone to facilitate deep cannulation (i.e., precut sphincterotomy; see Chapter 14). Subsequent use of a standard sphincterotome or balloon dilation of the precut site allows for stone removal. It is possible to simply extend the cut using the needle knife and deliver the impacted stone.

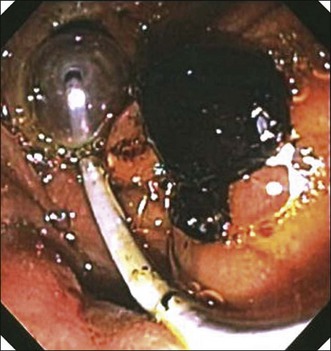

In cases where a stone is impacted at the ampullary orifice as can be seen in patients with acute biliary pancreatitis (Fig. 18.2), a polypectomy snare can be applied above the impacted stone and closed around the bulging papilla beyond the stone. The wire loop ensnares the bulging papilla and prevents the stone from migrating. With a gentle tug on the closed snare, the impacted stone can be expelled from the orifice.19 Subsequent sphincterotomy can be performed if residual stones are present in the bile duct. A biliary stent can be placed to ensure drainage and prevent cholangitis if there is concern of stasis from a swollen papilla.

Balloon Stone Extraction

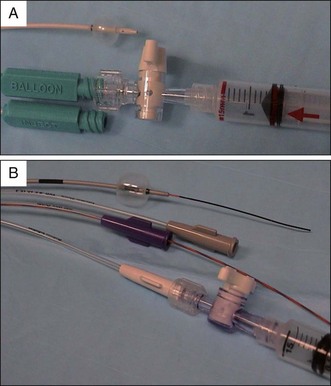

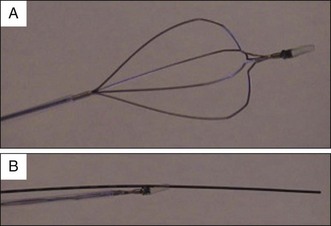

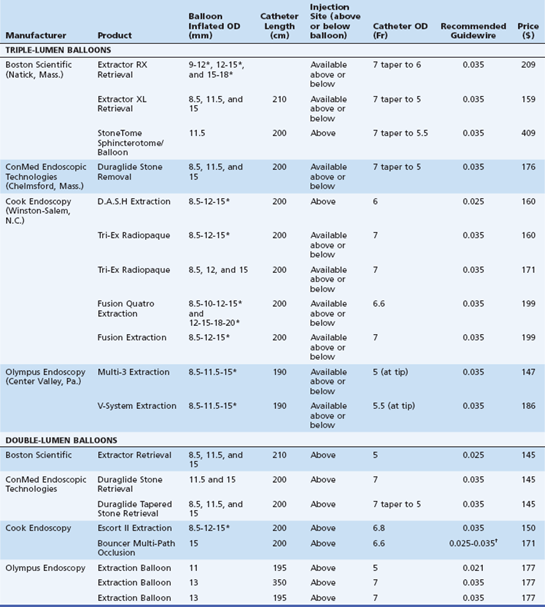

Extraction balloons are available in various sizes ranging from 8.5 to 18 mm (Table 18.1).20 Extraction balloons are composed of a single balloon mounted on the tip of a catheter. Most balloons can be inflated with air to one, two, three, or four preset sizes, although the size of the balloon can be adjusted by injecting air into the balloon and regulating the volume with a two-way stopcock (Fig. 18.3, A). To size the diameter of the exit passage (sphincterotomy or bilioenteric anastomosis) prior to stone extraction and avoid stone impaction, the balloon is inflated to the widest diameter of the common bile duct below the level of the stone and pulled back gently to determine if there is any resistance to traction removal of the balloon while noting any significant deformity of the balloon fluoroscopically. In cases of chronic pancreatitis where the intrapancreatic portion of the bile duct may be compressed or fixed, the balloon may deform or become “sausage shaped.” This suggests there will be resistance to stone extraction. Triple-lumen balloons allow the catheter to be passed over a guidewire and maintain access to the biliary system while also maintaining the ability to inject contrast (Fig. 18.3, B). However, triple-lumen balloon shafts may be stiffer than regular double-lumen balloons and slightly more difficult to pass into the bile duct. The tip of the balloon catheter may be curled gently before introduction into the endoscope to facilitate cannulation. An additional drawback to triple-lumen catheters is that the diameter of the contrast port is quite small, which limits the ability to inject adequate volumes of contrast, especially in a dilated biliary tree.

Table 18.1 Stone Extraction Balloons

*Indicates variable balloon preset size based on volume of inflation.

†Wire exits catheter below balloon.

From ASGE Technology Committee, Adler DG, Conway JD, et al. Biliary and pancreatic stone extraction devices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70(4):603-609, Table 1.

Once the catheter is within the bile duct, the balloon is inflated above the stone and pulled back gently until the stone is at the level of the papilla. The endoscope should be aligned so that the axis of traction is in the same axis as the bile duct. The tip of the endoscope is then angled upward against the sphincterotomy. While maintaining gentle traction on the balloon catheter at the level of the biopsy valve, the tip of the endoscope is deflected downward, expelling the stone from the sphincterotomy (Fig. 18.4). If there is resistance, the tip of the endoscope is again angled upward with steady traction applied to the catheter, and the flip-down movement of the endoscope tip is repeated to remove the stone. It may be necessary to maintain the traction on the balloon as the stone is slowly eased out of the bile duct. If necessary, the endoscope tip can be angled downward and rotated to the right to exert more traction force to expel the stone. It is important to remember that an overinflated balloon may give rise to resistance as it is being pulled down, and it may be necessary to deflate the balloon slowly (using the stopcock as a control) to conform to the size of the bile duct. If multiple stones are present, one should first remove the most distal stone and then remove the next most proximal stone and continue until complete stone clearance is achieved.

The advantage of using an extraction balloon over a basket is that the inflated balloon fully occludes the lumen of the bile duct, facilitating removal of small stones and debris. In addition, an air-free occlusion cholangiogram can be performed to ensure complete clearance of the bile duct (see Fig. 18.1, C). This is obtained after inflating the balloon just below the bifurcation, withdrawing air from the intrahepatic ducts and withdrawing the balloon while injecting contrast. Furthermore, the balloon catheter can be inserted over a guidewire, allowing access to the intrahepatic ducts and removal of intrahepatic stones.

Basket Stone Extraction

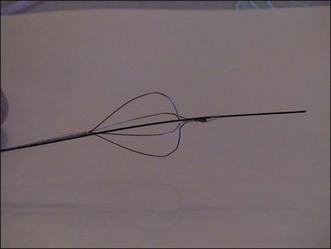

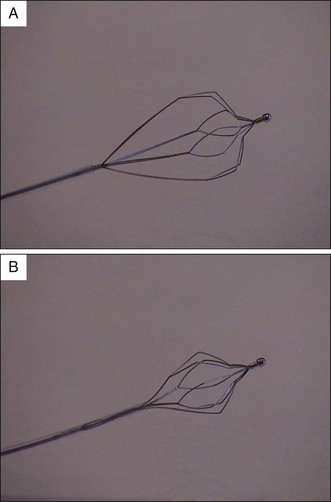

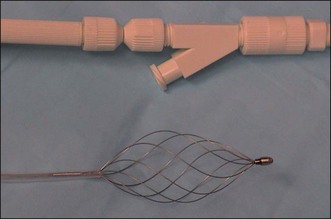

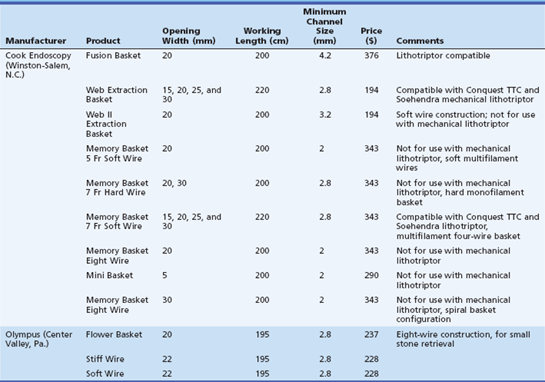

Wire baskets are frequently used for stone extraction. A variety of baskets are available in different sizes and configurations, which allows engagement of stones varying from 5 mm up to 3 cm in diameter (Table 18.2).20 However, stones larger than 2 cm often cannot be extracted in one piece and require fragmentation prior to removal. The four-wire Dormia basket is the most commonly used stone retrieval basket (Fig. 18.5). It is hexagonal in shape and composed of braided steel or nitinol wires. The stone is engaged between the wires when the basket is closed and removed by continuous traction upon basket withdrawal. Small stones may be difficult to capture with standard baskets that have large gaps between the wires. A flower basket (Olympus America, Center Valley, Pa.) has a modified design such that the top part of the basket is further divided into eight wires, giving rise to a smaller mesh size for improved stone engagement when the basket is closed. Small stones are thus more easily trapped than with the regular four-wire basket (Fig. 18.6).

Table 18.2 Stone Extraction Baskets

From ASGE Technology Committee, Adler DG, Conway JD, et al. Biliary and pancreatic stone extraction devices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70(4):603-609, Table 2.

Spiral baskets are also available and may be used to remove relatively small stones (Fig. 18.7). In the spiral configuration, the wires close around the stone as the basket is pushed open. However, spiral baskets are not designed for mechanical lithotripsy. A variety of baskets are available that are compatible with mechanical lithotripsy devices and are designed to engage large stones. The basket wires are much stronger and when used with a lithotripsy device can be used to mechanically crush the stone without breaking. Traction or tension can be applied to the wires either manually or with the help of a special crank handle (Soehendra mechanical lithotriptor, Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, N.C.; BML-110A-1, Olympus America) that is used to tighten the basket wires around the stone and fragment it.

Contrast can be injected through the basket to outline the stones in the bile duct. One should avoid injecting excessive amounts of contrast to reduce the risk of displacing the stone upward into the intrahepatic system. When a single-lumen basket is used, the basket should be opened slightly to allow free flow of dilute contrast. A double-lumen basket allows both injection of contrast through the basket channel and passage of a guidewire through a separate channel. Alternatively, the basket can be advanced over a previously positioned guidewire. This is especially helpful for the removal of intrahepatic stones or stones that may have migrated into the intrahepatic ducts. Traditionally, the guidewire goes through the entire length of the basket catheter. With the short wire system, only a short length of the basket actually goes over the guidewire and manipulation is done with the wire locked in position. A further modification is the “ropeway” basket, which is a single-lumen system that has a short catheter attached to the tip of the basket, allowing only the tip (instead of the shaft) of the basket to go over the guidewire (Fig. 18.8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree