■ Iatrogenic injuries—commonly during retraction of the transverse colon/stomach or during left upper quadrant laparoscopic operations

■ Hemoglobinopathies

■ Hereditary spherocytosis (HS)

■ Thalassemia/sickle cell disease

■ Splenic cysts (e.g., epithelial or epidermoid cysts)

■ Splenic hamartomas

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ Prior to elective surgery, a thorough history should be obtained, including an account of abdominal pain or constitutional symptoms, detailed past medical/surgical history, and all current medications and allergies. Particular attention should be directed to eliciting any symptoms of liver disease, clotting or bleeding disorders, and a blood product transfusion history.

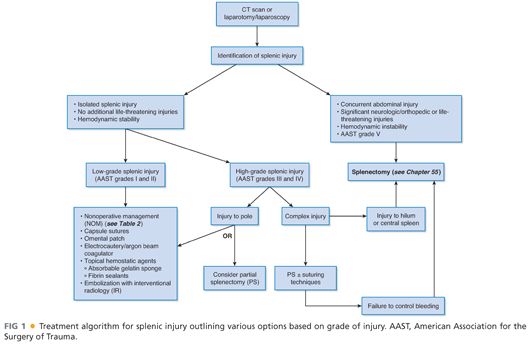

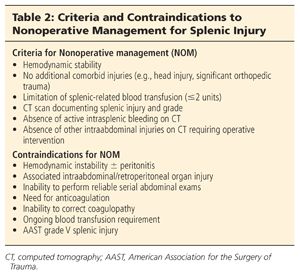

■ Patients presenting with splenic trauma require rapid assessment making use of the principles outlined in the American College of Surgeons Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS®) protocol. Hemodynamic instability is a general contraindication to splenorrhaphy. A thorough history should be obtained as outlined earlier. Particular attention must be paid to associated injuries as these will influence decisions regarding nonoperative management (NOM), splenorrhaphy, or splenectomy (FIG 1). In pediatric patients, NOM is the preferred treatment choice and early consultation with a pediatric surgeon is highly recommended. Adult trauma patients with low-grade splenic injuries may be managed with NOM (Table 2).

■ Patients presenting with hemoglobinopathies have abnormal laboratory profiles and often present with abdominal pain/discomfort, a history of jaundice, or splenomegaly. Rarely, patients will be completely asymptomatic. Patients with HS often present with sequestration of abnormal red blood cells (RBCs) and may have splenomegaly.2,3 Historically, these patients benefited from splenectomy. Recently, clinical evidence demonstrates that patients with HS are amenable to partial splenectomy (PS), eliminating the need for repeat transfusions and significantly reducing the risk of overwhelming postsplenectomy infection (OPSI). Additionally, patients with sickle cell anemia have shown improvement following PS.2−4

■ A complete and thorough physical examination should be performed on all patients. The presence or absence of splenomegaly should be noted. All signs of portal hypertension or liver failure should be elicited. Presence or location of surgical scars must be considered prior to determining operative approach.

■ Splenorrhaphy is best performed via an open technique, which allows full visualization of the injury. An open approach allows easy conversion to a splenectomy should the clinical situation warrant this. Elective PS may be performed via an open or laparoscopic technique. Laparoscopic PS requires substantial experience in minimally invasive surgery and therefore, we prefer an open or a laparoscopic-assisted technique.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ All patients with a suspected or known hemoglobinopathy require input from a hematologist. Patients should have a blood smear and/or bone marrow analysis, a complete blood count (CBC), and specialized blood studies as indicated by the disease process.

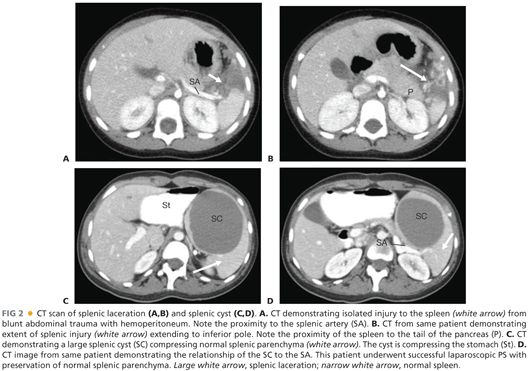

■ Computed tomography (CT) scanning should be performed for all hemodynamically stable patients with suspected splenic trauma. CT is an excellent modality for preoperative planning to evaluate injury extent and to delineate vascular anatomy. CT is recommended for elective PS to determine the relationship of the spleen to adjacent organs, splenic size, and potential locations of accessory spleens (FIG 2).

■ Ultrasound (US) is a noninvasive imaging modality to assess for splenomegaly, presence of splenic cysts/masses, and determination of portal hypertension in selected patients. US is particularly useful in assessing the spleen in children with the added advantage of minimizing ionizing radiation exposure. In the evaluation of trauma patients, focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) is an accepted screening tool to diagnose intraperitoneal fluid or blood. Preoperative US should be performed for all patients with symptomatic biliary colic and patients with hemoglobinopathies to evaluate for cholelithiasis. Patients with cholelithiasis should be considered for concurrent cholecystectomy.

■ Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a recognized method for evaluating splenic lesions without the use of ionizing radiation. MRI is not recommended in the setting of splenic injury.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■ Patients undergoing PS for elective indications should receive vaccinations for encapsulated organisms (Haemophilus influenzae B, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Neisseria meningitidis) 2 to 4 weeks prior to surgery. Although PS should theoretically eliminate the risk of OPSI, vaccinations should be administered in the event that a total splenectomy is performed. Patients undergoing PS in the setting of splenic injury should receive vaccinations 2 to 4 weeks postoperatively. Current guidelines for OPSI prevention are outlined in Chapter 55, Table 2.

■ Blood products should be ordered and available intraoperatively including packed red blood cells (PRBCs), platelets, and fresh frozen plasma (FFP).

■ All patients should receive prophylactic antibiotics to cover skin flora within 60 minutes prior to the skin incision.

■ Appropriate antithrombotic precautions should be instituted, including sequential compression devices (SCDs) for all patients age 12 years and older. Appropriate anticoagulation medications (e.g., low-molecular-weight heparin) should be administered preoperatively per hospital protocol.

■ A nasogastric tube (NGT) should be inserted following induction of anesthesia to decompress the stomach and aid in visualization. Consideration should be given to leaving the NGT in situ for 24 to 48 hours postoperatively to prevent gastric distension.

■ An open approach is recommended for patients undergoing splenorrhaphy for splenic injury. The human hand as a retractor to provide compressive hemostasis is invaluable in the successful performance of PS. This approach also provides good exposure and allows for possible splenectomy should attempts at splenorrhaphy prove unsuccessful.

■ PS may be performed by a laparoscopic approach in the elective setting. Laparoscopic PS requires advanced laparoscopic skills and should only be undertaken by a surgeon familiar with the procedure.

■ In adult splenic trauma patients, consideration should be given to preoperative splenic artery embolization (SAE) by interventional radiology. SAE has been demonstrated to improve the use of NOM, with improvement in splenic salvage, length of hospital stay, and mortality.5 Pediatric patients with splenic trauma rarely require embolization and consultation with a pediatric surgeon is highly recommended before treatment with SAE is commenced.6

Positioning

■ For open splenorrhaphy, patients are placed in a supine position with both arms extended. For patients with isolated splenic trauma, an upper midline incision from the xiphoid process to the umbilicus allows adequate exposure. This incision can be extended inferiorly if additional exposure is required or other intraabdominal injuries are identified. For pediatric patients, a left subcostal incision or a transverse incision starting at the left 12th rib tip can be used (see Chapter 55, FIG 5).

■ Patients undergoing laparoscopic PS can be positioned supine with both arms tucked at the side. A beanbag or kidney rest is placed under the left flank to increase exposure between the 12th rib and iliac crest. The table may be rotated to allow near-supine positioning for port placement and then rotated during the operation to achieve a right lateral decubitus position. As with all operations, all pressure points should be appropriately padded (see Chapter 55, FIG 4).

TECHNIQUES

SPLENORRHAPHY

Incision

■ A variety of incisions can be used to perform splenorrhaphy depending on the clinical situation.

■ Trauma patients. A midline incision extending from the xiphoid process to the pubis is used to enter the peritoneal cavity. This incision allows maximal exposure. A quick thorough inspection of each quadrant and the pelvis should be performed. Active bleeding should be immediately addressed. Retractors should be placed to maximize visualization and determine if additional sources of bleeding are present. All fluid and particulate matter should be quickly evaluated. Additional abdominal/retroperitoneal injuries discovered at the time of laparotomy should be prioritized and dealt with as outlined in corresponding chapters.

■ Isolated splenic injury. A midline incision extending from the xiphoid process to the level of the umbilicus can be used. Should additional exposure be required, the incision can be extended inferiorly. Retractors are placed to allow maximal exposure of the left upper quadrant. If a splenic injury occurs while performing an upper abdominal laparoscopic procedure, consideration should be made to convert to an open procedure depending on the extent of the injury. For higher grade injuries (American Association for the Surgery of Trauma [AAST] grades III and IV), a left subcostal incision can be made approximately 3 cm inferior to the costal margin (see Chapter 55, FIG 5).

■ Pediatric patients. A midline incision can be used similar to adult patients in the setting of trauma. For isolated splenic injuries, either a left subcostal incision or a transverse incision can be used. For a transverse incision, the tip of the 12th rib is identified and the incision is extended medially to allow for exposure of the spleen.

Mobilization

■ Anatomically, the spleen resides superiorly and posteriorly in the left upper abdomen. For adequate assessment of a splenic injury and successful splenorrhaphy, the spleen must be completely mobilized by removing all peritoneal and visceral attachments. This includes the splenophrenic attachments to the diaphragm, the splenocolic ligament to the splenic flexure of the colon, the splenorenal ligaments, and the gastrosplenic ligament (see Chapter 55, FIG 6). The splenophrenic and splenorenal ligaments are avascular and can be divided sharply. Conversely, the gastrosplenic ligament (containing short gastric vessels) and the splenocolic ligament require careful attention to ensure excellent hemostasis. Vessels in these ligaments should be ligated with ties or an energy-based sealant device.

■ Division of the ligaments begins first with the splenocolic ligament, allowing the splenic flexure of the colon to be mobilized away from the spleen. Splenic mobilization is further achieved by the operating surgeon placing their left hand posteriorly on the spleen (a laparotomy pad may improve the grip) and rotating it anteromedially. This maneuver will better expose the splenophrenic and splenorenal ligaments. Once the spleen is free of these attachments, it can be carefully mobilized into the wound. The gastrosplenic ligament is then carefully divided. Laparotomy pads can be carefully placed posteriorly to further aid in mobilization.

■ Division of the ligaments should be made 2 to 3 cm from the spleen to avoid injury to both the spleen and adjacent organs (i.e., pancreas).

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree