Chapter 15 Sphincter of Oddi Manometry

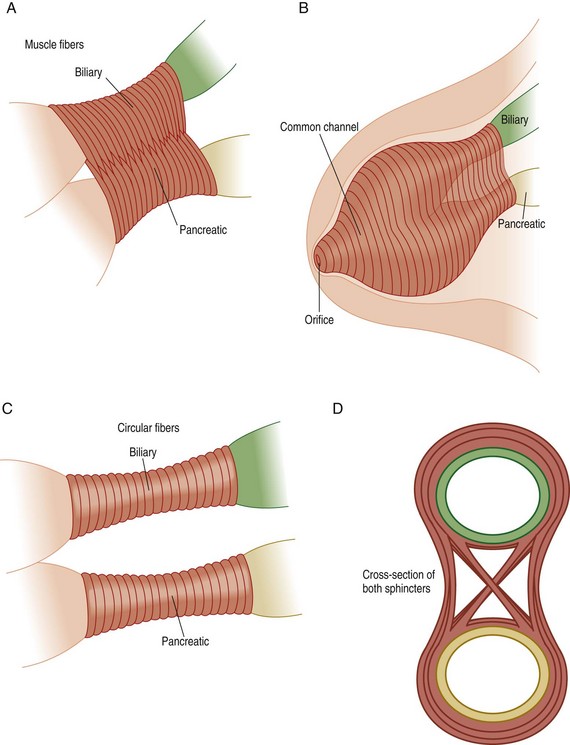

The sphincter of Oddi (SO) is a complex smooth muscle structure surrounding the terminal common bile duct, the main pancreatic duct, and the common channel, when present (Fig. 15.1). The high-pressure zone generated by the sphincter varies from 4 to 10 mm in length. The SO regulates the flow of bile and pancreatic exocrine juice and prevents duodenum-to-duct reflux (i.e., maintains a sterile intraductal environment). The SO possesses a basal pressure and phasic contractile activities; the former appears to be the predominant mechanism regulating flow of pancreatobiliary secretions. Although phasic SO contractions may aid in regulating bile and pancreatic juice flow, their primary role appears to be maintaining a sterile intraductal milieu.

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD) refers to an abnormality of sphincter of Oddi contractility. It is a benign noncalculous obstruction to the flow of bile or pancreatic juice through the pancreatobiliary junction (i.e., the SO). This may cause pancreatobiliary pain, cholestasis, and/or recurrent pancreatitis. The most definitive development in our understanding of the pressure dynamics of the SO came with the advent of sphincter of Oddi manometry (SOM). SOM is the only available method to measure SO motor activity directly.1,2 SOM is considered by most authorities to be the most accurate means to evaluate patients for sphincter dysfunction.3,4 Although SOM can be performed intraoperatively5–7 and percutaneously,8 it is most commonly done in the endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) setting. The use of manometry to detect motility disorders of the SO is similar to its use in other parts of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. However, performance of SOM is more technically demanding and hazardous, with adverse event rates (in particular, pancreatitis) approaching 20% in several series. Its use, therefore, should be reserved for patients with clinically significant or disabling symptoms. One needs to appreciate, however, that SOM is not likely an independent risk factor for post-ERCP pancreatitis when the aspirating manometry catheter is used (see discussion below). Questions remain as to whether the short-term observations (2- to 10-minute recordings per pull-through) reflect the “24-hour pathophysiology” of the sphincter.9–13 Despite these problems, SOM is gaining more widespread clinical application. In this review we discuss the technique of SOM, with an emphasis on the technical and cognitive skill sets required.

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Method of SOM

Sedation

SOM is usually performed at the time of ERCP. The initial step in performing SOM, therefore, is to administer adequate sedation, which will result in a comfortable, cooperative, and motionless patient. All drugs that relax (anticholinergics, nitrates, calcium channel blockers, glucagon) or stimulate (narcotics, cholinergic agents) the sphincter should be avoided for at least 8 to 12 hours prior to manometry and during the manometric session. Early studies with midazolam and diazepam suggested that these benzodiazepines do not interfere with sphincter of Oddi manometric parameters and therefore are acceptable sedatives for SOM.14–18 While one study did demonstrate a decrease in mean basal sphincter pressure in 4 of 18 patients (22%) receiving midazolam,19 these results have not been duplicated to date. Opioids had traditionally been avoided during SOM because of indirect evidence suggesting that these agents caused SO spasm.20–26 However, two prospective studies27,28 have demonstrated that meperidine, at a dose of ≤1 mg/kg, does not affect the basal sphincter pressure but does alter phasic wave characteristics. Since the basal sphincter pressure generally is the only manometric criterion used to diagnose SOD and determine therapy, meperidine may be used to facilitate conscious sedation for manometry. Recent preliminary data also suggest that a low dose of fentanyl, administered topically, does not affect the basal sphincter pressure.29 Confirmatory data are awaited. Patients referred for SOM may take large doses of narcotics on a daily basis and frequently prove difficult to sedate at ERCP. Adjunctive agents for conscious sedation therefore have been sought. Our group demonstrated that droperidol did not significantly alter SOM results; concordance (normal versus abnormal basal sphincter pressure) was seen in 30 of 31 patients.30 Wilcox and colleagues,31 on the other hand, suggested that droperidol did in fact influence SOM parameters. However, in their series of 41 patients, ERCP and SOM were carried out under general anesthesia in all but 7 patients. While it has been suggested that SO motor function is not influenced by general anaesthesia,1 the effects of newer anesthetic agents are unknown, making interpretation of their results problematic. More recently, ketamine did not significantly alter SOM parameters, with concordance noted in 28 of 30 (93%) patients.32 Limited experience with propofol suggests that this drug also does not affect the basal sphincter pressure,33,34 but further study is required before routine use of ketamine or propofol for SOM is recommended. If glucagon must be used to achieve cannulation, a 15-minute waiting period is required to restore the sphincter to its basal condition.

Equipment

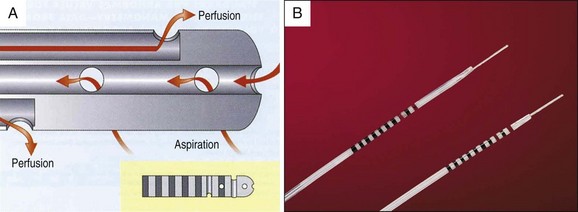

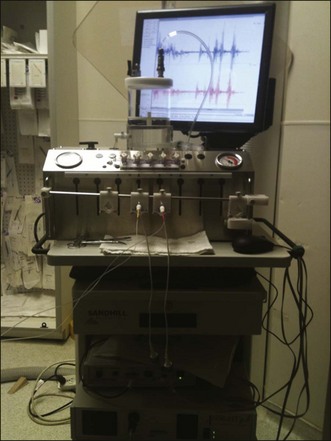

Virtually all standards have been established with 5 Fr catheters; therefore these should be used. Triple-lumen catheters are state of the art and are available from several manufacturers. Catheters with a long intraductal tip may help to secure the catheter within the bile duct, but such a long nose is commonly a hindrance if pancreatic manometry is desired. A sleeve catheter is a perfused channel system that records pressure along its length, potentially limiting motion artifacts during performance of SOM.35 Limited data from Australia suggest that this sleeve method is comparable to standard SOM with triple-lumen catheters,36 but more data are needed. Over-the-wire (monorail) catheters can be passed after first securing one’s position within the duct with a guidewire. Whether this guidewire influences basal sphincter pressure has not been definitively elucidated (see discussion below). Some triple-lumen catheters will accommodate a 0.018-inch-diameter guidewire passed through the entire length of the catheter and can be used to facilitate cannulation or maintain position in the duct. Guidewire-tipped catheters are also being evaluated. Early experience with performance of SOM using perfusion systems demonstrated unacceptably high postprocedure pancreatitis rates.37–40 Presumably, overdistension of small caliber pancreatic ducts may lead to this adverse event. Aspiration catheters (Fig. 15.2) in which one recording port is sacrificed to permit both end- and side-hole aspiration of intraductal juice and the perfusing fluid are therefore highly recommended for pancreatic manometry. These catheters have been shown to reduce the frequency of post-SOM pancreatitis while accurately recording sphincter pressures.39 Most centers prefer to perfuse the catheters at 0.25 mL/channel/min using a low compliance pump (Fig. 15.3). Lower perfusion rates will give accurate basal sphincter pressure measurements but will not give accurate phasic wave information. The perfusate generally is distilled water, although physiologic saline needs further evaluation. The latter may crystallize in the capillary tubing of perfusion pumps and must be flushed out frequently. Solid state catheters40,41 and microtransducer manometry systems42 are also available and have been used by some investigators in an attempt to avoid volume loading of the biliopancreatic system during perfusion manometry.41 Preliminary data from a few centers demonstrate comparable SOM results to those achieved with perfusing catheters.40,42

Technical Performance of SOM (Video 15.1)

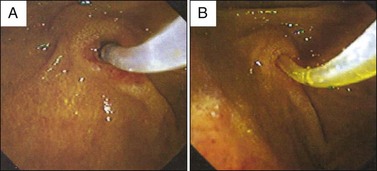

SOM requires selective cannulation of the bile duct and/or pancreatic duct. Maximal efficiency is achieved by combining ERCP and SOM in a single session. It is preferable to perform cholangiography and/or pancreatography prior to performance of SOM, as certain findings (e.g., common bile duct stone) may obviate SOM. This can simply be done by injecting contrast media through one of the perfusion ports. Alternatively, the duct entered can be identified by gently aspirating on any port (Fig. 15.4). The appearance of yellow fluid in the endoscopic view indicates entry into the bile duct. Clear aspirate indicates that the pancreatic duct has been entered. This technique may prove useful when attempting to access the bile duct following pancreatic SOM, as repeated pancreatic duct injections may increase post-ERCP pancreatitis rates.43 If clear fluid is seen in the catheter, suggesting pancreatic duct entry, the catheter position is altered to achieve a more favorable angle for biliary cannulation. Blaut and colleagues44 have shown that injection of contrast into the biliary tree prior to SOM does not significantly affect sphincter pressure characteristics. Similar evaluation of the pancreatic sphincter after contrast injection has not been reported. One must be certain that the catheter is not impacted against the wall of the duct to ensure accurate pressure measurements. On occasion, selective deep cannulation of the desired duct may only be achieved with a guidewire. However, a recent study in our unit found that stiffer-shafted nitinol core guidewires used for this purpose commonly increase basal biliary sphincter pressure measured at ERCP by 50% to 100%.45 Therefore when wire-guided cannulation is performed, we recommend withdrawing the wire back into the catheter, outside of the duct and not traversing the sphincter, during performance of SOM. Alternatively, stiff guidewires need to be avoided or very soft–core guidewires must be used. Once deep cannulation is achieved and the patient is acceptably sedated, the catheter is withdrawn across the sphincter at 1- to 2-mm intervals by standard station pull-through technique. Ideally, both pancreatic ducts and bile ducts should be studied. Current data indicate that an abnormal basal sphincter pressure may be confined to one side of the sphincter in 35% to 65% of patients with abnormal manometry,46–51 and thus one sphincter segment may be dysfunctional and the other normal. Raddawi and colleagues48 reported that an abnormal basal sphincter pressure was more likely to be confined to the pancreatic duct segment in patients with pancreatitis and to the bile duct segment in patients with biliary-type pain and elevated liver function tests.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree