Sickle Cell Nephropathy: Introduction

The major clinical consequences of sickle cell disease (SCD) are crises from vascular obstruction by sickled cells and anemia because of red blood cell (RBC) destruction. The obstruction can cause hematuria and renal papillary necrosis (RPN) with a defect in tubular function, especially in urinary concentration. The chronic consequences include sickle cell glomerulopathy, more indirectly related to sickling, and a specific form of renal malignancy.

Hematuria & Renal Papillary Necrosis

- Acute gross hematuria or persistent microscopic hematuria.

- Without RBC casts or dysmorphic (other than sickle) RBCs.

- Ultrasound or helical computed tomography (CT) shows distinctive medullary abnormalities.

Hematuria in SCD is a specialized form of the sickle crisis, the consequence of renal medullary sickling, vascular obstruction, and RBC extravasation. The low PaO2, high osmolality, and acidic environment of the renal medulla lead to sickling.

The renal pathology associated with isolated hematuria, shows relatively insignificant changes, primarily medullary congestion. The later RPN in SCD is a focal process, with some collecting ducts surviving within a diffuse area of fibrosis. The relevant medullary pathology in SCD is found in the region of the collecting ducts, the inner medulla, and the papilla. Within the medullary fibrosis the vasa rectae are destroyed, following initial dilation and engorgement. The RPN of SCD contrasts with the RPN observed in analgesic abuse, in which the vasa rectae typically are spared, and most lesions occur in peritubular capillaries. Because calyces are affected separately and sequentially in SCD, acute obstruction and renal failure are uncommon.

Gross and often painless hematuria is dramatic and is usually unilateral (L>R) due to increased left renal vein pressure. Hematuria occurs at any age and is more often seen with a (higher gene frequency) sickle trait (HbAS).

RPN is usually discovered by radiologic investigation of patients with painless gross hematuria. However, hematuria is not invariably present in RPN, with no difference in the incidence between symptomatic (65%) and asymptomatic (62%) patients. RPN can be found even in young children.

Acute renal failure is not uncommon in SCD; it is seen most often with infections and evidence of rhabdomyolysis, and in patients with lower hemoglobin (Hb) (˜6.4 versus 8.7 g/dL). Volume depletion is a common precipitating cause. It is likely that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are partly responsible for some episodes of acute renal failure, in view of the maintenance of the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in SCD by prostaglandin mechanisms.

Rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation has been seen, albeit rarely, in those with sickle trait who undergo rigorous military training, and there is an apparently increased risk of sudden unexplained death in patients with sickle trait.

Priapism is a specialized vasoocclusion of the penis, which was found as often as 42% in one series. A painful, hot, tender erection, most often on waking, lasts up to 3 hours. This can be preceded by days or weeks of “stuttering.”

A drop in Hb is unusual in acute hematuria.

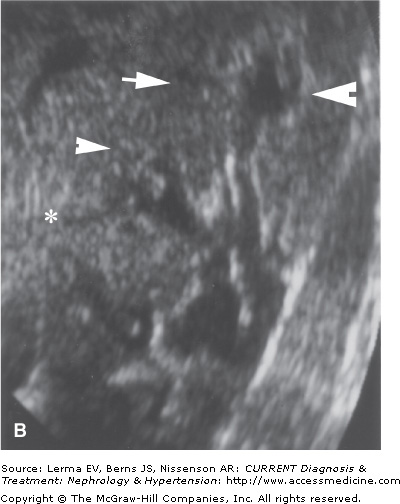

Increased echodensity of medullary pyramids on ultrasound is typical of SCD, and in the absence of hypercalciuria, medullary echodensity in a patient with hematuria should suggest a sickle hemoglobinopathy (Figure 49–1).

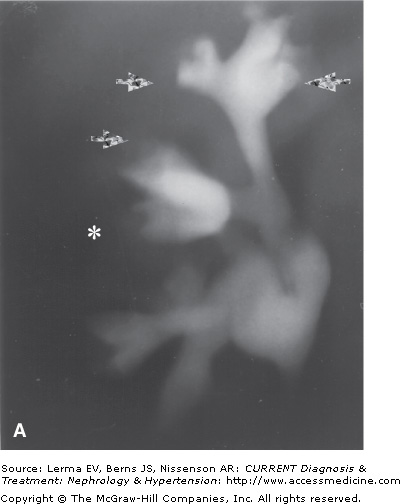

Figure 49–1.

A: Tomographic pyelography of an 18-year-old patient with abdominal pain and hematuria. Papillary necrosis is evident from blunted medullary cavities, especially the upper pole (closed arrows). The bases of the calyces are preserved. The middle pole calyx has a possible sinus tract (*). B: Ultrasonographic visualization of the same kidney. The middle pole exhibits deep extensions into the papilla, likely sinus tracts, typical of the “papillary” form of RPN. (Reproduced with permission from Scheinman JI: The kidney in sickle cell disease. In: Primer on Kidney Diseases. Greenberg A (editor). Academic Press, 1998.)

In one series, 39% of 189 patients had at least calyceal clubbing and 23% had definite RPN. Cortical scarring, as found in pyelonephritis, should not accompany the calyceal clubbing of SCD, but a history of infection appears more common in RPN in SCD. A “medullary” form of RPN is common, with an irregular medullary cavity, often with sinus tracts. Sonography can sometimes identify the early medullary form of papillary necrosis. Later, a distinctive “garland” shadowing pattern of calcification of the medullary pyramids can be present.

Unusually, pyelography has been done when SCD was not recognized. Helical CT can detect RPN earlier than sonography. Ultrasound reflectivity in young SCD patients (aged 10–20 years) has found diffuse or medullary echogenicity in a minority of patient, a finding that is not RPN.

Sickle cell crises are painful episodes of vasoocclusion, often accompanied in the second or third day by fever without documented infection. The abdominal crisis is similar to a “surgical” abdomen but usually without rebound tenderness. In the presence of gross hematuria, the origin of the pain is often assumed to be the kidney, but careful palpation of the kidneys should be distinctive.

Continued or persistent gross hematuria likely represents a form of renal “sickle crisis” in a known HbSS or HbAS patient. Other treatable causes of hematuria, including the recently described distinctive renal medullary carcinoma in patients with sickle hemoglobin, must be excluded. Severe pain makes the diagnosis of renal sickle crisis less likely, whereas moderate discomfort often lateralizes the bleeding. Renal and bladder ultrasound can rule out bleeding from a stone or tumor and may aid in the diagnosis of RPN (see below).

In view of the benign pathology in SCD hematuria, conservative management is appropriate. Bed rest is often recommended to avoid dislodging hemostatic clots.

It is advisable to maintain high rates of urine flow by encouraging increased intake or infusion of hypotonic fluids (4 L/1.73 m2 surface area per day) combined with administration of diuretics (a thiazide or a loop diuretic such as furosemide), which should help clear clots from the bladder. The resulting diuresis would reduce medullary osmolarity, which would help to alleviate sickling in the vasa rectae. Sodium-containing fluids may tend to increase sodium retention (see below).

Alkalinization of the urine by 8–12 g NaHCO3 (per 1.73 m2) per day may reduce sickling in a urine environment, but this may not be relevant to medullary sickling. The O2 affinity of Hb is theoretically increased in a more alkaline environment.

After failure of treatment with fluid administration and alkalinization, ϵ-aminocaproic acid (EACA) can be tried to inhibit fibrinolysis, allowing clots to mediate hemostasis. The effective dosage in an adult is 8 g/day.

Arteriographic localization and local embolization of the involved renal segment may avoid nephrectomy, only rarely required for uncontrolled bleeding.

Newer surface-active polymers may abort sickle crises, and could possibly abort the acute hematuria of SCD.

General treatment strategies for SCD, by decreasing the proportion of rheologically abnormal cells, can reduce the risk of recurrence of cerebral vasculopathy and probably other complications. These include frequent transfusions and measures to increase fetal Hb including 5-azacitidine and hydroxyurea.

Tubular Dysfunction