Chronic Tubulointerstitial Nephritis: Introduction

Chronic interstitial nephritis (CIN) is by definition tubulointerstitial nephritis that has failed to resolve on its own or has been resistant to whatever treatment was rendered after several months or years. However, it can also arise de novo as a consequence of chronic, low-grade, or injurious exposures of the tubulointerstitium to the culprit agent, ie, medication, physical factor, infectious agents, etc. Such exposures may be intermittent or persistent. Histopathologically, it is characterized by the presence of interstitial chronic inflammation, interstitial fibrosis, and tubular atrophy (Figure 37–1).

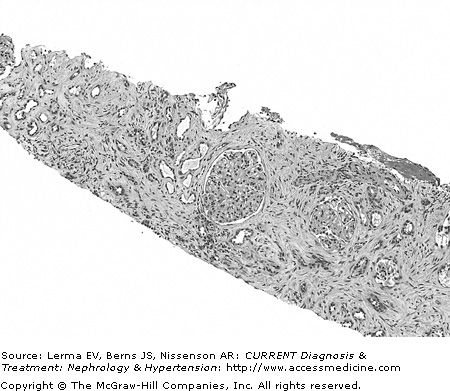

Figure 37–1.

Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis with interstitial fibrosis, fibroblasts, and scattered mononuclear inflammatory cells. There is extensive tubular atrophy and loss. Glomeruli are spared. Hematoxylin and eosin (×200). (Courtesy of Dr. Shane Meehan, Department of Pathology, University of Chicago.)

Depending on the culprit agent, the disease may have a particular predilection for either the proximal tubules, the distal tubules, or both. The functional abnormalities usually depend on the tubular site of involvement, ie, distal tubule dysfunction may be characterized by acidosis and hyperkalemia, as seen in obstructive uropathies, whereas injury involving the renal medulla is characterized by an impaired ability to concentrate urine as seen in sickle cell nephropathy (Table 37–1).

Electrolyte and acid–base disorders |

Proximal RTA or Fanconi syndrome |

Myeloma |

Dent disease |

Cystinosis |

Sjögren’s syndrome |

Distal RTA |

Bacterial pyelonephritis |

Reflux nephropathy |

Lithium |

Lead |

Myeloma |

Light chain disease |

Lupus nephritis |

Hypercalcemia |

Hyperkalemia (Type 4) RTA |

Reflux nephropathy |

Lead |

Lupus nephritis |

Sickle cell nephropathy |

Sodium wasting |

Clinical syndromes |

Kidney stones |

Hypercalcemia |

Hyperoxaluria |

Uric acid nephropathy |

Dent disease |

Sarcoidosis |

Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus |

Lithium |

Cisplatin |

Hypokalemia |

Hypercalcemia |

Dent disease |

ARF |

Pyelonephritis |

Analgesic nephropathy |

Lithium |

Calcineurin inhibitors |

Cisplatin |

Myeloma |

Lymphoma |

Lupus nephritis |

Hypercalcemia |

Uric acid nephropathy |

Radiation nephritis |

Papillary necrosis |

Acute pyelonephritis |

Analgesic nephropathy |

Sickle cell nephropathy |

As CIN progresses, there may be concomitant glomerular abnormalities, probably secondary to maladaptive alterations in the glomeruli or a result of the tubulointerstitial processes. At that time, patients may present with nephrotic-range proteinuria, which can cloud the primary underlying disease process.

Primary or idiopathic |

Epstein–Barr virus |

Secondary |

Infections |

Polyoma virus |

Pyelonephritis (acute and chronic) |

Drugs |

Analgesic abuse nephropathy |

Lithium-induced renal disease |

Acyclic nucleoside inhibitors (Chapters 14 and 35) |

Calcineurin inhibitors |

Aristolochic acid/Chinese herb nephropathy |

Chemotherapeutic agents: Cisplatin, ifosfamide, carmustine |

Heavy metals |

Lead nephropathy |

Cadmium |

Hematologic diseases (Chapter 33) |

Multiple myeloma |

Lymphoproliferative disorders |

Light chain disease |

Sickle cell nephropathy (Chapter 49) |

Obstructive uropathy (Chapter 16) |

Reflux nephropathy (Chapter 39) |

Immune-mediated diseases |

Sarcoidosis |

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome |

Tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis (TINU) |

Idiopathic hypocomplementemic |

Interstitial nephritis |

Metabolic disorders |

Hyperoxaluria |

Hyperuricemia/hyperuricosuria |

Hypercalcemia/hypercalciuria (Chapters 6 and 40) |

Hypokalemic nephropathy |

Genetic disorders |

Cystinosis (Chapter 40) |

Dent disease |

Miscellaneous |

Endemic (Balkan) nephropathy |

Radiation nephritis |

Primary or Idiopathic

The localization of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) DNA in the proximal tubule cells in patients with CIN of unknown etiology has suggested a causative role for the Epstein–Barr virus. However, further studies need to be done to demonstrate if a true cause and effect of EBV renal scarring actually exists.

In immunosuppressed individuals, such as transplant recipients, BK polyoma virus infection has been shown to cause interstitial nephritis. The virus has been demonstrated in the transitional cells in the urine (so-called ‘decoy cells’) via urine microscopy, but correlation with renal allograft function status and histologic evidence of renal involvement is very poor. Accurate diagnosis of BK polyomavirus infection requires a very high index of suspicion. Electron microscopy is very sensitive in depicting the presence of BK virions, but the finding of viral particles is not by itself diagnostic. An increase in CD20 and a decrease in cytotoxic T cells in allografts is characteristic of polyoma virus infection.

Clinically, it is difficult to distinguish interstitial nephritis versus acute cellular rejection.

Management of patients with polyoma virus nephropathy is difficult since there is no specific antiviral therapy available at this time. Aside from reducing immunosuppressive therapy, other novel treatments include IVIg and Cidofovir. The latter is also nephrotoxic, and has been described to cause acute interstitial nephritis.

Secondary Infections

Acute pyelonephritis (discussed in more detail in Chapter 38) is classified under the category of complicated urinary tract infections. Patients clinically present with a combination of symptoms that includes fever and chills, dysuria, urgency, and increased frequency. They commonly complain of flank discomfort with a physical correlate of costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy usually reveals an active urinary sediment consisting of leukocytes and leukocyte casts, and even red blood cells (RBCs) on occasion.

Histopathologically, there is infiltration of polymorphonuclear cells and lymphocytes and edema grossly distorting the normal tubulointerstitial architecture.

The majority of cases respond to appropriate antibiotic therapy targeting the causative organism, which is most commonly a gram-negative Escherichia coli. In those who do not respond to antimicrobial therapy readily, or who develop recurrent infections, there may be renal scarring and possible progression to chronic pyelonephritis.

Chronic bacterial infections of the urinary tract are among the most common causes of chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis (CTIN). The majority of these cases are associated with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), hence the term “reflux nephropathy” (discussed in more detail in Chapter 39). However, for those not associated with VUR, the disease is termed “chronic pyelonephritis.”

Clinically, patients with chronic pyelonephritis present with fever and chills, dysuria, vague flank or back pain, as well as hypertension. Some patients may present with tubular abnormalities such as impaired urinary concentrating ability, hyperkalemia, and salt wasting, all of which reflect distal tubular dysfunction. Chronic or repeated urinary tract infections are predisposing risk factors.

Examination of the urine often reveals an active urinary sediment consisting of leukocytes and leukocyte casts. Grossly, the kidneys appear contracted.

Histopathologically, the findings are similar to other forms of CTIN, with tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis. Lymphocytes and mononuclear cells predominate in the chronic inflammatory infiltrative population.

Persistent chronic pyelonephritis can progress to a localized infection called “xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis.” Its exact pathogenesis is unknown. Typically, there is an underlying urinary tract obstruction, eg, nephrolithiasis, which is complicated by the infection, leading to ischemia and destruction of renal parenchymal tissue, with granuloma formation subsequent to the accumulation of lipid deposits. These lipid deposits are actually lipid-laden macrophages, called “foam cells.”

The symptoms are similar to those of chronic pyelonephritis, including hypertension. Characteristically, a distinct mass may be palpable over the affected “nonfunctioning” kidney. Urine cultures are usually positive for E coli and other gram-negative bacilli or Staphylococcus aureus.

Computed tomography (CT), the imaging modality of choice, demonstrates that the kidney is significantly enlarged. Other findings include the predisposing renal calculus as well as low-density masses or xanthomatous tissues. Neoplastic renal disease must be excluded among the differentials.

On intravenous pyelography (IVP) the involved kidney may contain a localized “abscess-looking” area that may look like a complex cyst or tumor. This is usually distinguished by either magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or CT.

Current treatment recommendations consist of appropriate coverage with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics combined with total or partial nephrectomy.

Medication-Related Chronic Interstitial Nephritis