contraction of the bulbocavernosus muscle (somatomotor innervation) leads to the pulsatile emission of the ejaculate from the urethra. During ejaculation, the alkaline prostatic secretion is discharged first, followed by spermatozoa and finally, seminal vesicle secretions (ejaculate volume 2-5mL). The seminal vesicles contribute 2mL, prostate 0.5mL, and Cowper’s glands 0.1mL of the ejaculate. There is an additional vasal and testicular contribution (accounting for around 5-10% of the total ejaculate volume).

Table 13.1 Phases of erectile process | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

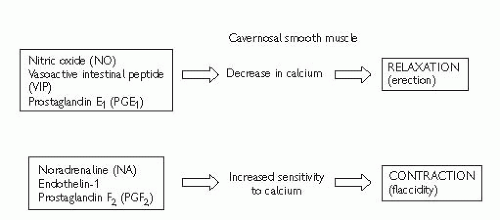

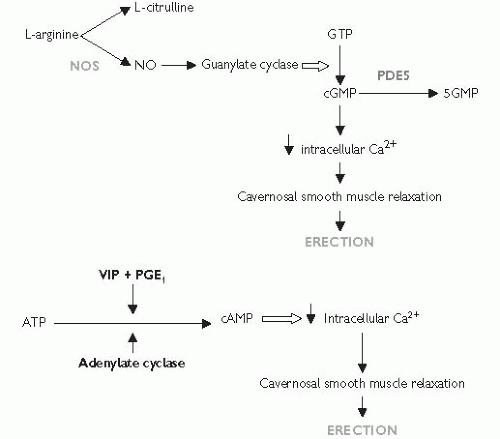

Fig. 13.2 Secondary messenger pathways involved in erection (ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Ca2+,calcium; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; GTP, guanosine triphosphate; NA, noradrenaline; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase enzyme; PDE5, phosphodiesterase type 5; PGE1, prostaglandin E1; PGF2, prostaglandin F2; VIP, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide). |

p. 575; Table 13.3); Brief Male Sexual Function Inventory (BMSFI); quality of life questionnaire (QoL-MED).

p. 575; Table 13.3); Brief Male Sexual Function Inventory (BMSFI); quality of life questionnaire (QoL-MED).testicles. The bulbocavernosus reflex can be performed to test integrity of spinal segments S2-4 (squeezing the glans causes anal sphincter and bulbocavernosal muscle contraction).

Blood tests: fasting glucose; serum (free) testosterone (taken 8.00-11.00 a.m.); fasting lipid profile are basic work-up tests.3 SHBG; U&E; LH/FSH; prolactin; PSA; thyroid function test should be selected according to patient’s history and risk factor profile.

Nocturnal penile tumescence and rigidity testing: the Rigiscan device contains two rings that are placed around the base and distal penile shaft to measure tumescence and number, duration, and rigidity of nocturnal erections. Useful for diagnosing psychogenic ED and for illustrating this diagnosis to patients.

Penile colour Doppler USS: measures arterial peak systolic and end diastolic velocities,* pre- and post-intracavernosal injection of PGE1.

Cavernosography: imaging and measurement of penile blood flow after intracavernosal injection of contrast and induction of artificial erection, used to identify venous leaks.

Penile arteriography: reserved for trauma-related ED in younger men. Pudendal arteriography is performed before and after drug-induced erection to identify those requiring arterial bypass surgery (although this is less commonly indicated now with the advent of modern penile prostheses).

MRI: useful for assessing penile fibrosis and severe cases of Peyronie’s disease.

Table 13.2 Causes of erectile dysfunction or ‘impotence’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Alprostadil (CaverjetTM).

pp. 596-7). It can improve the results of PDE5 inhibitors in hypogonadal men.

pp. 596-7). It can improve the results of PDE5 inhibitors in hypogonadal men.Table 13.4 A comparison of PDE5 inhibitors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree