(1)

Al Agouza, Cairo, PO, Egypt

4.1 Normal Anatomy and Histology

The scrotum consists of the skin, the dartos muscle, and external spermatic, cremasteric, and internal spermatic fasciae. The internal fascia is loosely attached to the parietal layer of the tunica vaginalis. The epidermis covers the dermis, and the deepest layer of the dermis merges with the smooth muscle bundles of the dartos tunic. Although scattered fat cells are present, there is no subcutaneous adipose tissue layer. The dermis contains hair follicles and apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous glands.

The scrotum contains the testes and the lower parts of the spermatic cords. The surface of the scrotum is divided into right and left halves by a cutaneous raphe which continues ventrally to the inferior penile surface and dorsally along the midline of the perineum to the anus. The left side of the scrotum is usually lower because of the greater length of the left spermatic cord.

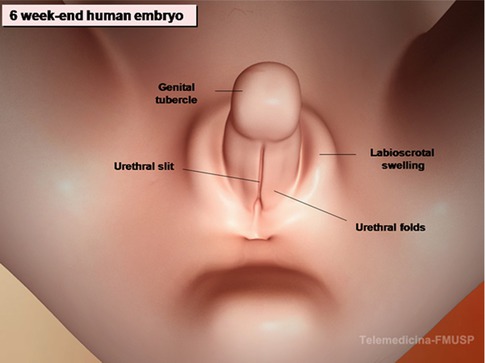

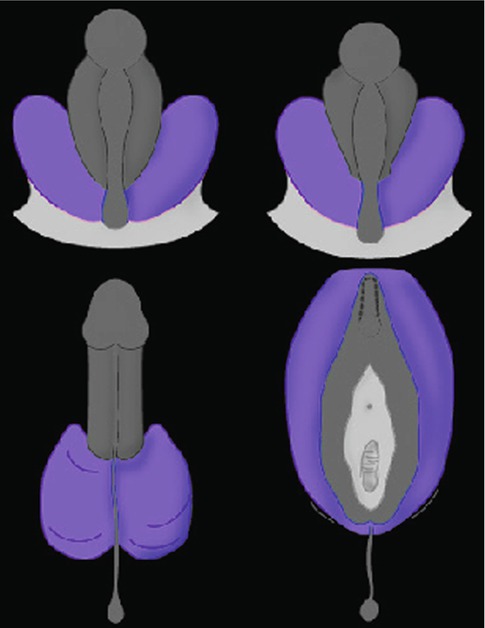

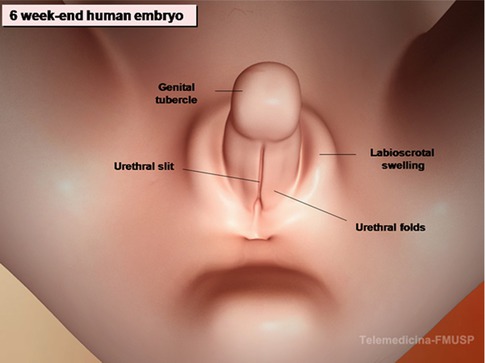

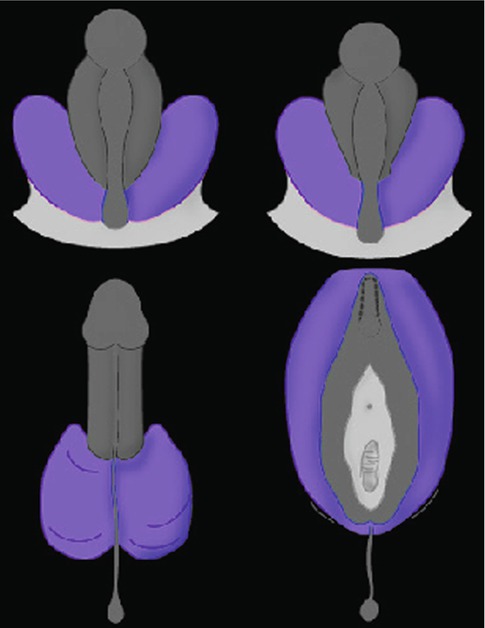

Embryologically, the scrotum originates from the genital swellings that meet ventral to the anus and unite to form the two scrotal sacs. A median raphe of fibrovascular connective tissue separates the two halves. The scrotum derives its blood supply from the external and internal pudendal arteries, and additional blood flows to it from the cremasteric and testicular arteries that traverse the spermatic cords. Lymphatic drainage of the scrotum is to the superficial inguinal nodes. Scrotal development is initiated in the 7th embryonic week with the formation of labioscrotal folds on either side of the urogenital folds. Fetal testosterone is converted into more potent dihydrotestosterone by the action of the enzyme 5α-reductase type 2, which is expressed in these tissues. The scrotum is then formed as a result of enlargement and midline fusion of the labioscrotal folds in response to the androgens (Fig. 4.1).

Fig. 4.1

Diagram of the development of the scrotum

4.2 Variant of Inguinal Hernia

Littre’s hernia

Amyand’s hernia

Richter’s hernia

4.2.1 Littre’s Hernia

Definition

Littre’s hernia is defined as any hernial sac which contains a Meckel’s diverticulum. It has been reported in association with inguinal, umbilical, femoral, sciatic, ventral, and lumbar hernias.

Historical Background

Littre reported this variant of inguinal hernia for the first time in 1700 [1].

Incidence

Inguinal Littre’s hernia is rare, particularly in children, in whom the umbilical variety is the more common variant.

Diagnosis

Littre’s hernia is difficult to diagnose, but should be suspected in a child with gastrointestinal bleeding, incompletely reducible hernias, and fecal hernial fistulas. It may be confused with cryptorchidism when Meckel’s diverticulum adheres to and envelops the testicle making palpation of the gonad difficult.

Recommended treatment is resection of the Meckel’s diverticulum from within the opened hernial sac followed by herniorrhaphy, rarely a laparotomy may be indicated [2].

4.2.2 Amyand’s Hernia

Historical Background

The first appendectomy was performed by Claudius Amyand on 1735 at St. George’s Hospital, London, on a child who had an inguinal hernia discharging feces from the groin, and this is before the record of the first removed acutely inflamed appendix through an abdominal incision in 1880 by Abraham Groves [3].

Incidence

Acute appendicitis or its complications in inguinal hernias are rare, and on presented as case reports, only 11 (0.13 %) of 8,692 cases of acute appendicitis occurred in external hernias (of all forms) [4].

Also, it was estimated that about 1 % of inguinal hernia repairs had the appendix detected in its contents (Fig. 4.2). However, the discovery of an acutely inflamed appendix within any hernial sac occurs in only 0.13 % of cases (Figs. 4.3 and 4.4).

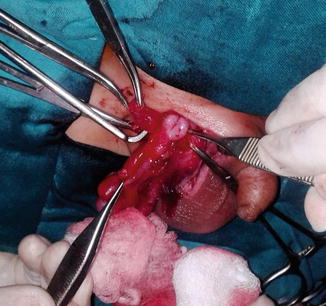

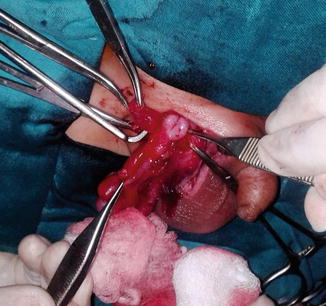

Fig. 4.2

Uninflamed appendix coming from opened hernial sac

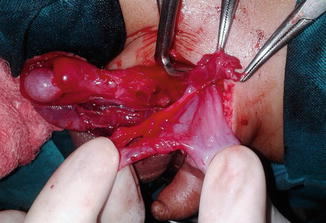

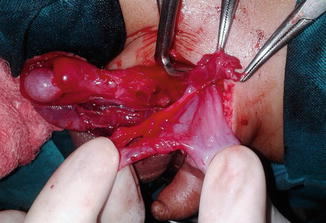

Fig. 4.3

Inflamed appendix in an inguinal hernia

Fig. 4.4

Amyand’s hernia

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is virtually never made preoperatively, strangulation being considered the likely diagnosis. Abdominal findings, pyrexia, and leukocytosis are not helpful in the differential diagnosis.

Appendectomy via the hernial sac is the treatment of choice, but a 50 % wound infection rate can be anticipated. Wound irrigation, drainage, and antibiotics would seem sensible ways of reducing wound sepsis.

If the inflamed appendix in the inguinal hernial sac is not detected early and perforation is complicating the case, a fecal fistula from the scrotum may result (Fig. 4.5).

Fig. 4.5

Scrotal fecal fistula

The natural urge to perform an appendectomy may be overwhelming, but appendectomy is not necessarily beneficial and may be detrimental.

Laparoscope-assisted diagnosis and treatment of Amyand’s hernia in children are rarely reported in literature. But laparoscopy had the advantages and feasibility to diagnose and also to treat such condition; it is safe and effective in these cases with good outcomes and worthy to be introduced [5].

4.2.3 Richter’s Hernia (Figs. 4.6and 4.7)

Figs. 4.6 and 4.7

Richter’s hernia

Historical Background

The earliest known reported case of Richter’s hernia was in 1598 described by Fabricius Hildanus, but the first scientific description of this particular hernia was given by August Gottlieb Richter in 1778, who presented it as “the small rupture.” In 1887, Sir Frederick Treves gave an excellent overview on the topic and proposed the title “Richter’s hernia” [6].

Definitions

Richter’s hernia is defined as an abdominal hernia in which only part of the circumference of the bowel is entrapped and strangulated in the hernial orifice. The segment of the engaged bowel is nearly always the lower portion of the ileum, but any part of the intestinal tract, from the stomach to the colon, may become incarcerated.

Incidence

The general rule is that approximately 10 % of strangulated hernias are Richter’s hernias. Richter’s hernias tend to progress more rapidly to gangrene than ordinary strangulated ones.

The dramatic increase in the use of laparoscopic surgery, creating a new site for development of Richter’s hernia, will undoubtedly be followed by an increase in its incidence. As our knowledge of this type of hernia increases, diagnosis will be made more easily and the condition suspected more often, thus avoiding the serious consequences of delay in treatment. Making the diagnosis of Richter’s hernia may be difficult because of the apparently innocuous initial symptoms and sparse clinical findings; the diagnosis may remain presumptive until clearly confirmed at surgery [6].

4.3 Variant of Hydrocele

Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck (female hydrocele)

Hourglass abdominoscrotal hydrocele

Meconium hydrocele

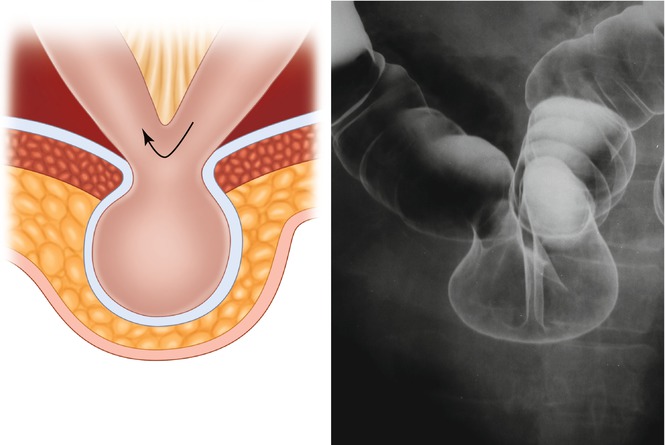

A hydrocele refers to a collection of fluid within a processus vaginalis and often presents in the male as a cystic scrotal mass that transilluminates brightly. In the female it is rare and it may present as a cystic mass in the inguinal area. A hydrocele can be communicating or noncommunicating. A communicating hydrocele fluctuates in size, being smaller when the baby is recumbent. Gentle pressure or squeezing reduces the fluid from the scrotum into the peritoneal cavity. Typically, the fluid reappears when there is increased intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., crying, straining). A noncommunicating hydrocele, on the other hand, is of stable size although the size may increase slowly. An abdominoscrotal hydrocele is an hourglass-shaped hydrocele that extends from the scrotum to the retroperitoneum but has no demonstrable communication with the peritoneal cavity. Pressure on the abdominal mass often causes enlargement of the scrotal component.

4.3.1 Hydrocele of the Canal of Nuck

Nomenclature

Hydrocele muliebris, female hydrocele, and the canal of Nuck cyst

The canal of Nuck in the female is analogous to the processus vaginalis of the male and is named after Anton Nuck, the seventeenth-century Dutch anatomist. During embryological development, the processus vaginalis is a peritoneal invagination into the inguinal canal, and in the female it accompanies the round ligament. In both sexes, it obliterates completely by the first year of life. When it fails to obliterate completely, it can result either in a congenital hernia or a hydrocele. Hydroceles are more common in the male probably because of the differences in migration of the gonads. A hydrocele can result from either a persistent patency of the processus vaginalis with peritoneal communication or with proximal obliteration at the deep ring with oversecretion and underabsorption in the distal segment. The canal of Nuck cyst is thin walled, contains clear fluid, and is lined by cuboidal or flattened mesothelial cells.

Historical Background

Coley in 1892 was the first one who described this condition in detail and reported 14 cases [7].

Incidence

There is a belief that the condition was sufficiently rare to warrant reporting a single case [8]. Recently with the increasing number of females with other neurologic problems which necessitate ventriculoperitoneal shunt of the excessive CSF, more cases of female hydrocele are reported.

Diagnosis

Normally the inguinal hydrocele of the canal of Nuck presents as a painless, translucent, irreducible lump in the groin. On ultrasound it is seen as an echo-free, well-defined, cystic tubular structure in the groin.

Two forms are recognized, the usual smaller form which may be contained wholly within the inguinal canal and the larger giant form which may extend beyond the level of inguinal canal (Fig. 4.8); for this differential diagnoses from femoral artery aneurysm and tuberculous abscess must be considered; transillumination test may be helpful to diagnose such cases (Fig. 4.9).

Fig. 4.8

A case of hydrocele of the canal of Nuck

Fig. 4.9

Transillumination test for a female hydrocele

Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck is an important differential diagnosis for an irreducible hernia in female patients. Clinically, these hydroceles may mimic both inguinal and femoral hernia and even present as strangulation. An associated inguinal hernia is reported in one-third of cases. They can also be mistaken for Bartholin’s cyst of the labium majus, which is relatively more common.

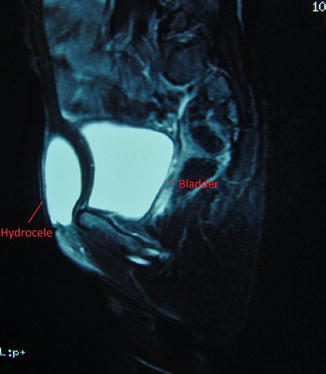

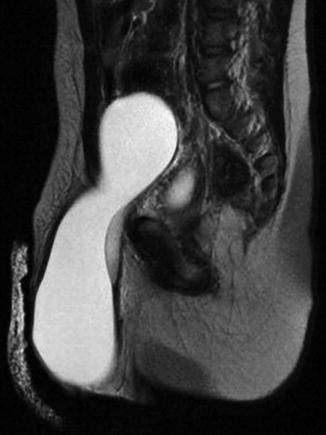

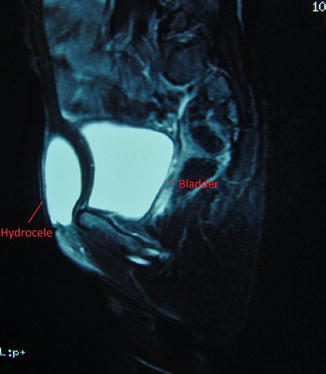

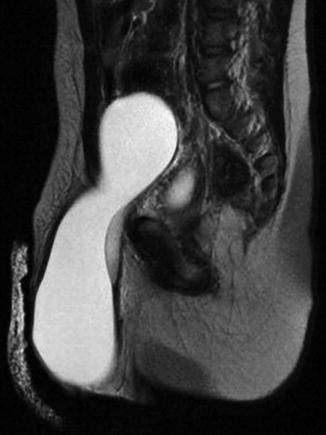

MRI may be indicated to diagnose some difficult cases (Figs. 4.10 and 4.11).

Fig. 4.10

MRI for a case of female hydrocele

Fig. 4.11

MRI for an abdominoscrotal hydrocele

The curative treatment of this condition is surgical excision of the cyst with closure of the neck at the deep ring (Fig. 4.12).

Fig. 4.12

Operative finding for a large female hydrocele

4.3.2 Abdominoscrotal Hydrocele (ASH)

Nomenclature

Hourglass hydrocele

Abdominoscrotal hydrocele is a rather rare condition which is difficult to differentiate from an inguinal hernia. In this condition, part of the sac is in the scrotum and another part is in the abdomen; they communicate by means of a narrow neck which occupies the inguinal canal, thus giving the hourglass effect. The intra-abdominal portion is usually larger and is extraperitoneal. The contained fluid will flow from one sac to the other, depending on the position of the patient, and in so doing will often make a noise that may be mistaken for the gurgle of a hernia.

While hydrocele is among the most common inguinal anomalies in children, less than 20 cases have been reported of its extreme form, the abdominoscrotal hydrocele (ASH), that lies deep to the narrow internal inguinal ring, but superficial to the peritoneal cavity proper, which is displaced superiorly and medially, sometimes reaching the lower pole of the kidney (Fig. 4.11). The pathophysiology of ASH is not clear. A one-way valve effect of the patent processus vaginalis may be one cause of the massive accumulation of peritoneal fluid in the ASH. Complete resection is curative, and the properitoneal approach should be considered.

4.3.3 Meconium Hydrocele

It is a sequence of meconium peritonitis due to intrauterine rupture of the alimentary tract as in cases of bowel atresia, where the meconium trickled down to the processus vaginalis [9]. It may be complicated with a scrotal fecal fistula or the quantity of meconium is too insignificant and the perforation was not so obvious so a case of scrotolithiasis may result (Sect. 4.11).

4.4 Ectopic Scrotum (ES)

Ectopic scrotum or scrotal ectopia, the anomalous position of one hemiscrotum along the inguinal canal, is a rare condition; it could be considered as an extreme spectrum of penoscrotal transposition which was discussed in Chap. 2 with penile anomalies, but ectopic scrotum is the bizarre unilateral form, and it should be differentiated from the accessory scrotum which had no testicular tissue, where only an extra scrotal tissue is detected. Polyorchia is another anomaly where the scrotum with extra testicles is contemporary.

Most commonly ectopic scrotum is suprainguinal (Fig. 4.13), although it may also be infrainguinal or perineal; few cases have been reported in the thigh or at the buttock. This anomaly has been associated with cryptorchidism, inguinal hernia, anorectal malformations, and closed cloacal exstrophy as well as the popliteal pterygium syndrome. In one review, 70 % of boys with a suprainguinal ectopic scrotum exhibited ipsilateral upper urinary tract anomalies, including renal agenesis, renal dysplasia, and ectopic ureter [10].

Fig. 4.13

Supra inguinal ectopic scrotum in a case of Popliteal Pterygium syndrome

The embryological explanation for the etiology of ES is not clear. It has been postulated that abnormalities in the development of the gubernaculum can cause abnormal scrotal positions, as the development of both of these structures is related anatomically and chronologically [11].

Although the gubernaculum is a prerequisite for the ultimate location of both the testis and scrotum, its role is complicated by the subsequent differential growth of the labioscrotal folds in which the gubernaculum is stabilized. If this interaction is disturbed, the result may be a suprainguinal ectopia, a penoscrotal transposition, or a perineal scrotum. A femoral ectopic scrotum, unlike the above, is the result of an aberrant gubernacular stabilization. While the etiology of these malformations is likely to be multifactorial, the existence of an inbred strain of rats characterized by a high incidence of an ectopic scrotum suggests a genetic component to this anomaly [12].

A study of this disorder indicated that an associated perineal lipoma was found in 83 % of these children; 68 % of those with a lipoma had no associated anomalies, where 100 % of those without a lipoma had associated genital or renal malformations [13].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree