Chapter 45 Sclerosing Cholangitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the biliary tree. It is characterized by stricturing and dilation of the intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts, with concentric obliterative fibrosis of intrahepatic biliary radicles. PSC is closely associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly ulcerative colitis (UC), which is found in approximately two thirds of Northern European PSC patients.1,2 The disease leads to chronic cholestasis but patients can be asymptomatic at presentation, diagnosed by abnormal liver enzymes, particularly elevation of the alkaline phosphatase, or they can present with pruritus, fatigue, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice. As the disease progresses, symptoms of cirrhosis can be manifested. PSC is associated with an unpredictable risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma in up to 30% of patients.3 The etiology and pathogenesis of PSC are unclear but it is likely an immune-mediated disease involving an exaggerated cell-mediated immune response leading to chronic inflammation of the biliary epithelium. A recent study has suggested that the incidence of PSC is rising in the Western world.4

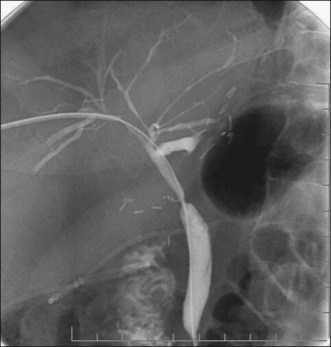

PSC is diagnosed by radiographic imaging of the biliary tree (Fig. 45.1 and Box 45.1). This has traditionally been performed using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) but more recently magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is thought to be as sensitive as ERCP in the diagnosis of PSC if the best equipment and operator are available (Fig. 45.2).

Box 45.1 Key Points

Diagnosis of PSC

ERCP ERCP |  MRCP MRCP |

Invasive Invasive |  Noninvasive Noninvasive |

Operator dependent Operator dependent |  Operator dependent Operator dependent |

Gold standard Gold standard |  Accuracy <100% Accuracy <100% |

Therapeutic Therapeutic |  Nontherapeutic Nontherapeutic |

Tissue sampling Tissue sampling |  No sampling No sampling |

Stage portal hypertension Stage portal hypertension |  Less expensive Less expensive |

No adverse events No adverse events |

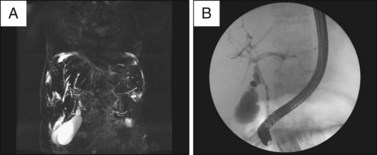

Fig. 45.2 A, Magnetic resonance cholangiogram of a patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis. The disease is relatively early without much attenuation of the intrahepatic biliary tree. The biliary radicles appear to be greater in diameter more peripherally and several discrete strictures are seen centrally. Both the left and right systems are involved but the extrahepatic duct is not well seen. The gallbladder is seen at the bottom left of the image. B, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram of the same patient with PSC as seen in Fig. 45.2, A.

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Diagnosis and Natural History

Introduction and Scientific Basis

Several studies have compared ERCP and MRCP in patients with clinical or biochemical evidence of cholestasis. MRCP has a comparable diagnostic accuracy of more than 90% and a specificity of 99%.5,6 However, many patients require a therapeutic intervention.6

Description of Technique

The technique for ERCP in PSC does not differ from the standard approach to biliary cannulation and is described elsewhere (see Chapter 13). In certain cases an occlusion cholangiogram is required using a stone-extraction balloon to prevent drainage of contrast from the biliary tree or filling of the gallbladder. However, care should be taken to avoid filling of segments of the intrahepatic ducts that subsequently cannot be drained, thus increasing the risk of infection. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends prophylactic antibiotics in cases where there exists the possibility of opacifying but not draining an obstructed bile duct. This scenario exists for all PSC patients and we treat all with antibiotics immediately before and for several days after ERCP.

Indications and Contraindications

Secondary causes of biliary sclerosis need to be excluded before a diagnosis of PSC can be confidently made. Biliary surgery, calculi and neoplasms, hepatic artery injury, hepatic arterial chemotherapy, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) can lead to strictures in the biliary tree. Figure 45.3 illustrates the cholangiogram of a patient several months following intraarterial chemotherapy with floxuridine (FUDR) with resultant toxic cholangiopathy.

Adverse Events

The adverse events of ERCP in the setting of PSC are typical of those for any other indication and are described in Chapter 7. There appears to be an increased risk of cholangitis despite the use of prophylactic antibiotics. A recent study examined 168 patients with PSC and 981 non-PSC patients undergoing ERCP over a 1-year period and noted no difference in the overall adverse event rate but a 4% incidence of cholangitis in PSC patients (compared to 0.2% in the non-PSC group), which correlated with the length of the procedure.7 In comparison to patients with biliary strictures from other diseases, ERCP in PSC patients appears to carry the same overall adverse event rate in elective cases (13%) but this can increase significantly in cases with an acute indication (29%).8

Relative Cost

Studies examining the relative cost of MRCP versus ERCP in the diagnosis of PSC have been conflicting and are affected by the prevalence of disease and the quality of imaging. One study suggested that the average cost per correct diagnosis by MRCP or ERCP, as the initial testing strategy in 73 patients with clinically suspected biliary disease, was $724 and $793, respectively. MRCP had a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 98%. MRCP thus resulted in cost savings when used as the initial test strategy for diagnosing PSC, particularly as there are essentially no procedure-related adverse events. However, this was in a cohort of patients with a 32% prevalence of PSC and with a very high specificity of MRCP. With a lower MRCP specificity (<85%) and a higher prevalence of PSC (>45%), ERCP becomes more cost effective, suggesting that ERCP should be used when the suspicion of PSC is high or if local MRCP facilities are suboptimal.9 The same study illustrated the high cost of dealing with adverse events of PSC. The average cost of managing post-ERCP adverse events was $2902, with a range of $1915 to $5032.

A more recent cost-effectiveness analysis suggested that in patients with suspected PSC an initial MRCP followed, if negative, by ERCP is the most cost-effective method in the workup of these patients.10

Endoscopic Treatment

Introduction and Scientific Basis (Box 45.2)

Box 45.2 Key Points

Endoscopic Therapy in PSC

Dominant strictures in PSC can be treated at ERCP.

Dominant strictures in PSC can be treated at ERCP.

More important than the stricture is the state of the prestenotic biliary tree.

More important than the stricture is the state of the prestenotic biliary tree.

Tissue sampling and liberal antibiotics are mandatory.

Tissue sampling and liberal antibiotics are mandatory.

Reserve treatment for patients with symptomatic jaundice.

Reserve treatment for patients with symptomatic jaundice.

Concomitant dilation with stenting may improve results.

Concomitant dilation with stenting may improve results.

Balloon dilation and short-term (10 to 14 days) stenting preferable.

Balloon dilation and short-term (10 to 14 days) stenting preferable.

Avoid sphincterotomy if possible.

Avoid sphincterotomy if possible.

More adverse events compared to diagnostic ERCP.

More adverse events compared to diagnostic ERCP.

No convincing data we are altering long-term natural history.

No convincing data we are altering long-term natural history.

Repeated endoscopy to maintain biliary patency may improve the survival of patients with PSC.11 By comparing the survival of 84 patients with PSC who underwent therapeutic ERCP (primarily treatment of dominant biliary strictures) over a mean 8-year follow-up period with the predicted 3-year or 4-year survival using the Mayo Clinic survival model for PSC, Gluck and colleagues demonstrated a significantly improved survival in the treated patients (p = 0.021). However, it should be remembered that the Mayo risk score weights bilirubin very heavily in its formula and therefore will be profoundly affected by stenting of a stricture with resultant rapid decrease in serum bilirubin. This raises the question of whether studies looking at outcome of therapy in highly selected jaundiced PSC patients can use this model, which was designed to assess slow longitudinal decompensation, as a comparison for a control group, following acute endoscopic interventions in these patients. Indeed, at least one study has found no change in cholestatic laboratory values in patients with and without dominant strictures after therapeutic ERCP.12

Description of Technique

Once biliary cannulation has been achieved there are a variety of instruments that can be used to perform stricture dilation (see Chapter 40). Wire access across strictures is the first step in therapy and soft tip wires with diameters of 0.018 to 0.035 in must be used to avoid perforation of the biliary tree. Push catheters have a tapered tip and the dilating part is typically 7 to 10 Fr in diameter. They are wire guided but their limited diameter and limited radial force mean that they are seldom used in PSC. More commonly inflatable balloons are employed. These are also wire guided but come in a variety of diameters (up to 12 mm) and have a greater radial force. They are difficult to use if the stricture is tortuous. A temporary plastic stent can be placed after dilation or in some cases can be placed without dilation. Any dominant stricture should undergo sampling for cholangiocarcinoma. We perform brush cytology (and molecular analysis in selected cases) and/or intraductal forceps biopsy. In cases of refractory strictures a screw catheter can be used over a wire, although there are no controlled data on its efficacy.

Published data on endoscopic therapy of dominant strictures in PSC patients are hampered by the lack of a standardized technique. Van Milligen de Wit and colleagues demonstrated technical success in 21 of 25 PSC patients with a dominant stricture who underwent endoscopic stent therapy.13 Of these 25 patients, 18 had a biliary sphincterotomy and 9 underwent dilation prior to stent insertion with either a balloon or a dilating catheter. Stents were exchanged electively every 2 to 3 months or if they became occluded. After a median follow-up of 29 months, 16 of the 21 patients had improved or stable liver tests. The same group demonstrated similar effectiveness using short-term stenting (mean of 11 days), with the benefit extending for several years. Improvements in symptoms and cholestasis were seen in all patients and these improvements were maintained for several years, with 80% of patients intervention-free at 1 year and 60% intervention-free at 3 years. There were 7 transient procedure-related adverse events in a total of 45 procedures and all but one was managed conservatively.14

The addition of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) to endoscopic therapy has been examined in a prospective trial by Stiehl et al. in 106 PSC patients, followed for up to 13 years, with improvement in overall survival rates compared with the Mayo PSC survival model.15 However, the use of high-dose UDCA (at 28 to 30 mg/kg) has recently been shown to increase the risk of adverse events in PSC patients, including death and the development of colorectal neoplasia, and hence is not recommended.16,17

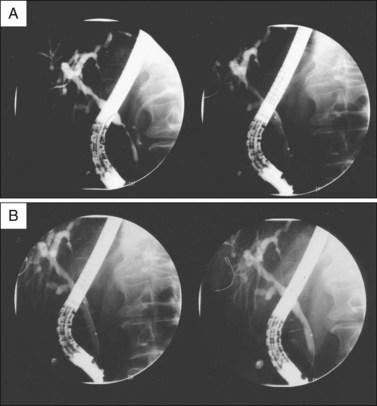

Our approach in PSC patients is to use therapeutic ERCP in patients with a dominant stricture with prestenotic dilation who have an elevated serum bilirubin or severe symptomatic cholestasis. We use balloon dilation over a guidewire, ensuring that the diameter of the balloon is no greater than the smallest diameter of the duct either proximal or distal to the stricture. The balloon is inflated until there is no waist in the balloon or to the maximum pressure (typically 10 to 12 atmospheres). We then leave a 10 Fr plastic stent across the stricture for 2 to 3 weeks and then repeat an ERCP and provide further therapy if indicated. All procedures are covered with prophylactic antibiotics and we use several days of oral antibiotics after the procedure to minimize the risk of cholangitis. Figures 45.4 and 45.5 illustrate dilation and stent therapy in patients with a dominant stricture.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree