Chapter 47 Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis

Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis (RPC) is a condition characterized by repeated attacks of bacterial infection of the biliary tract. It is believed that the initiating event is the entry of enteric flora into the biliary tree causing infection and inflammation and, through bacterial deconjugation of bilirubin diglucuronide, the formation of primary biliary stones.1 Persistent inflammation results in biliary strictures and stasis of bile in the biliary tree, which encourages further formation of stones leading to a vicious cycle of repeated or persistent inflammation and infection. There have been reports linking helminthiasis to RPC. Ascaris lumbricoides and Clonorchis sinensis worms have been identified in the biliary tract of patients with RPC.2 RPC has been most commonly reported in countries in the Asian Pacific region, including China, Taiwan, Japan, Korea, and in Southeast Asia and is distinctly uncommon in the Western world.3 However, it is a fast-declining disease even in these regions. Many patients are now elderly and present with adverse events of the disease such as cholangiocarcinoma (Box 47.1).4

Box 47.1

Key Points

Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis (RPC) is characterized by repeated attacks of cholangitis and the presence of intrahepatic strictures and stones.

Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis (RPC) is characterized by repeated attacks of cholangitis and the presence of intrahepatic strictures and stones.

Modalities of treatment include endoscopic retrograde cholangiography techniques, peroral cholangioscopy, percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy, and surgery.

Modalities of treatment include endoscopic retrograde cholangiography techniques, peroral cholangioscopy, percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy, and surgery.

Cholangioscopy requires skill and patience and involves the passage of a cholangioscope through a peroral or percutaneous transhepatic tract. Repeated procedures are usually needed.

Cholangioscopy requires skill and patience and involves the passage of a cholangioscope through a peroral or percutaneous transhepatic tract. Repeated procedures are usually needed.

Dilation of strictures with catheters and balloons and fragmentation of stones with electrohydraulic lithotripsy and laser may be necessary.

Dilation of strictures with catheters and balloons and fragmentation of stones with electrohydraulic lithotripsy and laser may be necessary.

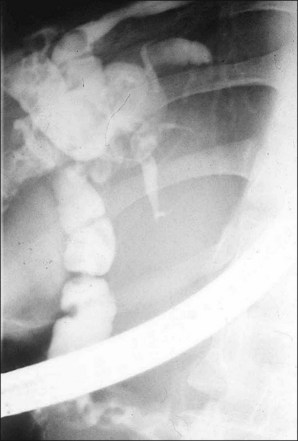

The hallmark of RPC is the presence of stones and strictures, which can be located in both intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts (Fig. 47.1; Video 47.1). The treatment of RPC is difficult and requires a multimodality approach encompassing endoscopy, radiologic techniques, and surgery. Successful treatment of RPC depends on the success in clearing stones, dilating strictures, and maintaining the patency of the stenosed ducts. Specific management aims at accurate localization of the pathology, application of specific techniques to remove stones, and dilating strictures. It serves to eliminate bile stasis and achieve control of cholangitis. Among the endoscopic techniques used are standard endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with or without peroral cholangioscopy, percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy (PTCS), and postoperative cholangioscopy through a T-tube tract.

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Initial Management of the Patient with Cholangitis

Patients with RPC often present with acute cholangitis. Acute cholangitis may be the first attack or a recurrent episode. These patients may develop septic shock rapidly. Initial management includes intravenous fluid replacement and the institution of intravenous potent, broad spectrum antibiotics. Emergency surgical decompression may be necessary in some patients but carries with it a high postoperative morbidity and mortality rate.5

Nonsurgical biliary drainage procedures provide an important alternative treatment option in these patients, especially in those with concomitant common bile duct (CBD) stones. Urgent ERCP with placement of a stent or a nasobiliary catheter has significantly reduced the mortality rate (Fig. 47.2).6 Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) may be necessary in patients with cholangitis associated with intrahepatic stones.7

Specific Treatment of Intrahepatic Stones

Description of Techniques

Standard ERCP and Peroral Cholangioscopy

Stones that are found in the extrahepatic bile duct and the main intrahepatic ducts can often be dealt with using conventional ERCP techniques of sphincterotomy and passing a basket and balloon into the appropriate ducts and extracting the stones. Strictures in the CBD or in the main intrahepatic ducts can be dilated with biliary dilating balloons of inflated diameters of 4 to 10 mm to facilitate passage of a retrieval basket for stone extraction. The use of a “through the scope” mechanical lithotriptor is helpful in crushing large stones. The usefulness of this approach is limited by the difficult access into the intrahepatic ducts. This is often due to angulated bile ducts, tight strictures, and impacted stones, making it difficult to pass and open a Dormia retrieval basket and sometimes even to pass a guidewire.8

Peroral cholangioscopy can be combined at the time of ERCP. There are several different approaches for the insertion of a thin caliber cholangioscope into the biliary tree. Mother-baby scope cholangioscopy is the first attempt but needs two experienced endoscopists, one for the mother scope and one for the baby scope. Single-operator peroral cholangioscope is also available. However, the image quality is not comparable to other types of videocholangioscope. Ultraslim upper endoscopes can be introduced into the biliary tree for direct peroral cholangioscopy (Video 47.2). This system offers excellent images and narrow band imaging is also possible. Since this endoscope offers a relatively large working channel, cholangioscope-guided biopsy and other therapeutic procedures are also possible (Video 47.3).9

Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangioscopy

1 Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage (PTBD)

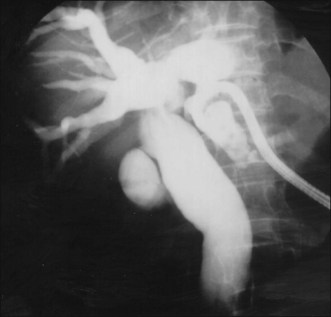

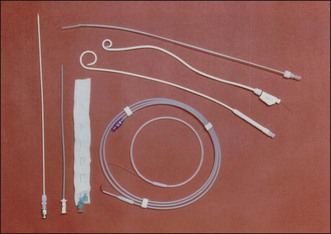

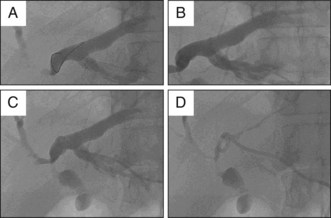

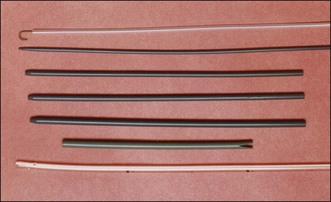

PTBD has been used to relieve obstructive jaundice, to drain infected bile, and to prevent or control cholangitis and sepsis.10 It is an initial step for creating a percutaneous tract and can be performed under fluoroscopic or ultrasonographic guidance.11 For PTCS, the site of PTBD is very important. If the puncture site is misplaced, there can be an acute angulation during the course to the target lesion (Fig. 47.3). Acute angulation is an important factor causing PTCS failure. Before selection of a PTBD site, the cholangioscopist or interventional radiologist should be familiar with the anatomy of the biliary tree. The ideal PTBD site is selected after meticulous review of several imaging studies such as ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) scan, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, or magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC). A PTBD kit is composed of puncture needles, a guidewire, dilators, and pigtail drainage tubes (Fig. 47.4). The usual diameter of an initial PTBD tube is around 6 to 8.5 Fr. For the initial puncture, the selection of a peripheral duct is important because the direct insertion of a PTBD tube into the central duct carries a significant risk of bleeding. Ultrasonography-guided puncture or fluoroscopy-guided puncture technique is commonly adopted for initial peripheral duct selection. After selective puncture of a peripheral duct, a guidewire is inserted and a bougienage dilator is pushed over the guidewire. After dilation of the tract, a pigtail catheter is introduced into the biliary tree (Fig. 47.5). In cases with a nondilated intrahepatic duct, PTBD carries a high risk of bleeding and biliary leakage. To prevent these adverse events, the insertion of an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube before PTBD and simultaneous cholangiography using this tube during PTBD is helpful in the accurate targeting of the desired intrahepatic duct.12

2 TRACT Dilation

For cholangioscopic examination of the biliary tree, the diameter of the percutaneous transhepatic tract should be larger than that of the cholangioscope. The cholangioscope diameter varies from 3.0 to 5.2 mm. Therefore the diameter of the percutaneous tract should be dilated to at least 11 to 12 Fr when an 11 Fr cholangioscope is to be used. In most centers the tract is dilated to 16 to 18 Fr because a cholangioscope with an outer diameter of 16 Fr is commonly used for therapeutic purposes. This dilation procedure can be performed with the aid of a specialized dilation kit (Fig. 47.6). The dilation process can be accomplished by “multistage” dilation or by “one-stage” dilation.13 Multistage dilation means reaching the fully dilated diameter of the percutaneous tract through several repeated dilations. The diameter of the PTBD tube is around 6 to 8.5 Fr at the first attempt. The tract can be dilated in stages every 2 to 4 days: to 10 to 12 Fr, then to 14 to 16 Fr, and finally to more than 18 Fr. In the “one-stage” dilation protocol, however, the PTBD tract is dilated to 16 or 18 Fr in a single session 2 to 4 days after the initial PTBD.

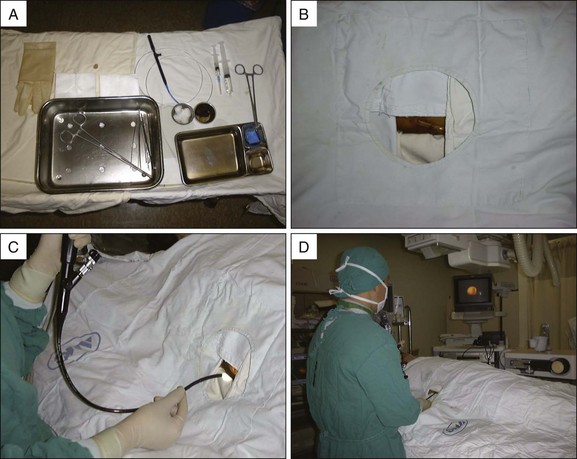

3 Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangioscopic Examination

Following full dilation of the percutaneous transhepatic tract, 10 to 14 days are usually required for maturation of the sinus tract at which time the cholangioscopic examination can be safely performed (Fig. 47.7). The patient is positioned in the supine position on the fluoroscopy table. The position of the cholangioscopist can be changed according to the site of PTBD. For example, when PTBD is performed on a right intrahepatic duct, the right side of the patient is the preferred position and when PTBD is done on a left intrahepatic duct, the left side of the patient is the preferred position. The video monitor and fluoroscopic monitor should be located at a favorable angle for the cholangioscopist. Premedication is required to relieve pain and anxiety using a combination of meperidine and midazolam or diazepam. The insertion of a cholangioscope into a fully dilated tract is not difficult. However, if the waiting period between the tract dilation and cholangioscopic examination is short, the insertion of the cholangioscope can be difficult and sometimes traumatic. The tract may collapse after removal of the dilation tube, especially during the first cholangioscopic examination. A guidewire, which is inserted before removal of the dilation tube, is used to smoothly guide the cholangioscope into the biliary tree.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree