Right and Extended Right Hepatectomy

Michael I. D’Angelica

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONSA right (segments V-VIII) or extended right (segments IV-VIII) hepatectomy (see Chapter 18 and Fig. 18.6) is most commonly indicated for primary liver or biliary malignancies (see Chapter 26) or for metastatic tumors, particularly metastatic colorectal cancer. Less frequently, this operation is indicated for large, symptomatic benign tumors or for large retroperitoneal tumors involving the right liver (see Fig. 23.3B). Rarely, liver or biliary infectious processes or bile duct injuries are an indication for a right or extended hepatectomy. Hepatic resections for live donor transplantation procedures are beyond the scope of this section and are not discussed.

Tumors involving the main inflow pedicle and/or outflow venous drainage to the right liver typically require right hepatectomy for removal. Similarly, this procedure is required for diffuse tumors involving most of the parenchyma or all segments of the right liver. It is important to recognize that the right liver accounts for a much larger proportion of the total liver volume compared to the left. Given that the volume of resected hepatic parenchyma, and therefore, the volume of the residual liver or the future liver remnant (FLR), closely correlates with postoperative morbidity, right and extended right hepatectomy are associated with a higher potential risk of postoperative hepatic failure compared to left or even extended left hepatectomy (see Chapter 18). More limited resections should, therefore, always be considered as an alternative approach (see Chapters 23 and 24). However, if such parenchymal-sparing resections are not possible, the surgeon must consider carefully the volume and quality of the FLR and consider preoperative portal vein embolization (PVE) of the right liver (see below and Chapter 18).

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNINGPatients with malignant tumors should have a complete extent of disease evaluation, with high-quality contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) of the abdomen and pelvis. A chest CT is generally indicated to rule out metastatic disease. In patients with primary liver cancer, a liver

protocol CT is the best means of assessing for multifocal hepatic disease (see Chapter 18), while CT angiography is most helpful for patients with biliary tract cancer, particularly hilar cholangiocarcinoma (see Chapter 26). In patients with metastatic cancer treated with preoperative chemotherapy, particularly hepatic colorectal metastases, hepatic steatosis is common, and CT may underestimate the hepatic disease extent. In such patients, MRI may be much more useful (see Chapter 18). Relevant tumor markers should be assessed to serve as a baseline and help monitor for recurrence after complete resection. Although beyond the scope of this chapter and dependent on the specific disease, other imaging such as 18FDG positron emission tomography or complete colonoscopy should be considered.

protocol CT is the best means of assessing for multifocal hepatic disease (see Chapter 18), while CT angiography is most helpful for patients with biliary tract cancer, particularly hilar cholangiocarcinoma (see Chapter 26). In patients with metastatic cancer treated with preoperative chemotherapy, particularly hepatic colorectal metastases, hepatic steatosis is common, and CT may underestimate the hepatic disease extent. In such patients, MRI may be much more useful (see Chapter 18). Relevant tumor markers should be assessed to serve as a baseline and help monitor for recurrence after complete resection. Although beyond the scope of this chapter and dependent on the specific disease, other imaging such as 18FDG positron emission tomography or complete colonoscopy should be considered.

High-quality imaging of the liver and its vascular and biliary anatomy are essential for planning operations. Triphasic scans including arterial, portal, and mixed phases provide information on the anatomy of the hepatic arterial system, portal venous system, and the hepatic veins. Information on the relevant anatomic relationships of tumors to these structures can help one plan the resection to avoid positive or close margins. In addition, vascular anomalies such as aberrant branches of the hepatic artery, portal vein, and hepatic veins can be assessed and anticipated at operation. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, although not mandatory, can be helpful in assessing biliary anatomy.

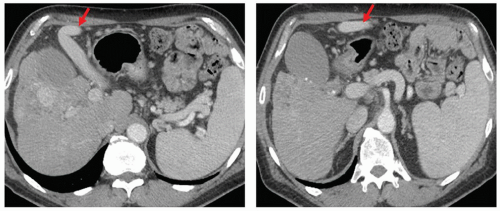

Assessment of hepatic function is critical and especially relevant for patients with chronic liver disease. Typically, an assessment of the Child-Pugh classification suffices, and in general, only Child-Pugh grade A patients are candidates for a right hepatectomy (see Table 18.1). The possibility of portal hypertension must be considered in patients with underlying liver disease and should be assessed since its presence portends prohibitive morbidity. Portal hypertension can manifest as a history of ascites or variceal hemorrhage, but more subtly, as splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of less than 100,000/mcl. Contrast-enhanced imaging can also demonstrate portal hypertension with findings such as a patent umbilical vein or gastro-esophageal varices (Fig. 19.1). If there is doubt as to the diagnosis of portal hypertension, a hepatic vein wedge pressure can be obtained. In general, patients with normal liver function, Child-Pugh grade A function, and without portal hypertension are candidates for a right hepatectomy.

Right and extended right hepatectomy are large volume resections and each case should be considered for preoperative right PVE. Volumetric studies are useful to

determine the relative volume of the FLR. If the FLR volume is under 25% to 30% in a normal liver, preoperative PVE should be considered. Patients with chronic liver disease should probably be considered for PVE at larger FLR volumes. Patients must be assessed for their medical and physical fitness to tolerate a major abdominal operation and its potential complications. Particular attention should be paid to physical fitness, performance status, and cardiopulmonary co-morbidities.

determine the relative volume of the FLR. If the FLR volume is under 25% to 30% in a normal liver, preoperative PVE should be considered. Patients with chronic liver disease should probably be considered for PVE at larger FLR volumes. Patients must be assessed for their medical and physical fitness to tolerate a major abdominal operation and its potential complications. Particular attention should be paid to physical fitness, performance status, and cardiopulmonary co-morbidities.

SURGERY

SURGERYPertinent Anatomy

Hepatic artery: The right hepatic artery typically runs in the porta hepatis from left to right, posterior to the common hepatic duct, but in about 10% of cases is found anterior to the bile duct. Replaced or accessory right hepatic artery branches are common, originating from the superior mesenteric artery and generally coursing posteriorly in the portacaval space.

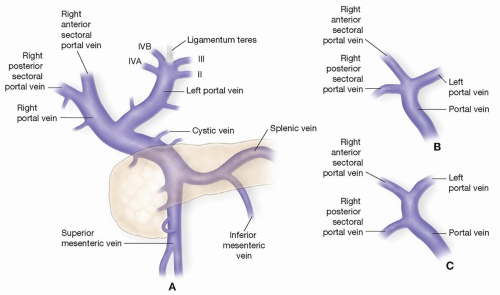

Portal vein: The right portal vein typically has a short extrahepatic course and branches into anterior and posterior sectoral branches. Sometimes there is no common right portal vein but rather a trifurcation of the main portal vein into right posterior, right anterior, and left branches. The right anterior portal vein branch can also arise separately from the left portal vein (Fig. 19.2). The right portal vein almost always gives off a small branch to the caudate process before entering the substance of the right liver, and this branch should be controlled if the right vein is to be divided extrahepatically.

Bile ducts: Typically a short right hepatic duct divides into anterior and posterior sectoral branches. These sectoral ducts (most commonly the posterior sectoral duct) can be found to drain into the left bile duct. The right sectoral ducts can also exit the liver and join the common hepatic or bile duct inferiorly in the porta hepatis.

The surgeon should recognize that variability in the biliary anatomy is more commonly associated with the right hepatic duct.

Hepatic veins: Large accessory right hepatic veins are relatively common and are encountered early in the caval dissection. When these are present, branches from the right adrenal vein are occasionally found draining into the accessory right hepatic vein. A large vein draining segment VIII typically drains medially into the middle hepatic vein, and is a common source of bleeding deep in the parenchymal dissection.

Positioning, Incisions, and Retractors

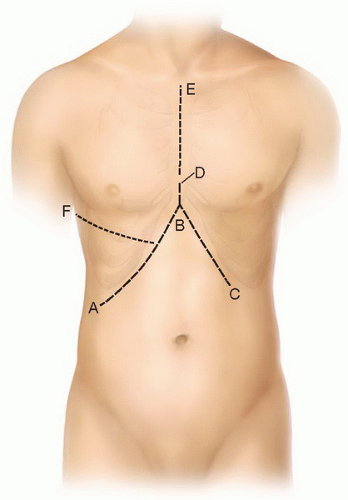

The patient is positioned supine with the arms extended out at right angles allowing for easy peripheral vascular access and monitoring. There are numerous incisions that allow access to the right liver. A bilateral subcostal incision is commonly used and can be extended to the xiphoid in the midline. In our experience, this “Mercedes”-type incision is usually not necessary and results in a high ventral hernia rate. We typically use a right subcostal incision with midline vertical extension to the xiphoid (“hockey stick” incision). Some surgeons use a thoracoabdominal incision with entry into the right chest and division of the diaphragm. While we find this to be rarely necessary, it can be helpful when there is severe right-sided atrophy or when exposure of the suprahepatic vena cava is difficult due to a large mass. The thoracoabdominal incision can be a simple J-type incision or an extension of the “Mercedes” or “hockey stick” incision into the chest (Fig. 19.3). The key issue for exposure is cephalad retraction of the costal margin at approximately a 45 degree angle. Any number of retractor systems can provide this retraction combined with lateral retraction of the right chest wall and inferior retraction of the lower abdominal viscera (see Fig. 18.8).

Anesthetic Considerations

The most common source of bleeding from the hepatic parenchyma is from the hepatic veins. Maintaining a low central venous pressure (CVP) during resection is invaluable in limiting blood loss (see Chapter 18). While some anesthesiologists place central venous catheters for CVP monitoring, it is quite simple for the surgeon to visualize the vena cava during the operation to assess it and communicate with the anesthesiologist.

The vena cava should not appear bulging or “full” but rather should have respiratory variation and be somewhat “collapsing”. Mild Trendelenburg position, limitation of intravenous fluids, and pharmacologic management with venodilators are helpful. Once the resection is completed the anesthesiologist should be informed to hydrate the patient. Communication between the surgeon and the anesthesiologist is critical.

Exploration

Diagnostic laparoscopy is used selectively based on the risk of occult unresectable disease.

Thorough open exploration for occult metastatic disease, precluding resection should include bimanual palpation of the liver, as well as inspection/palpation of all peritoneal surfaces and relevant nodal basins.

Intraoperative hepatic ultrasound is used routinely to identify occult hepatic tumors and assess the details of the tumor and vascular anatomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree