6 Retropubic Synthetic Midurethral Slings

Introduction

Retropubic MUS were developed in the mid-1990s in an attempt to create a minimally invasive surgical treatment for SUI. Up until this time incontinence procedures were aimed at suspending or supporting the proximal urethra and bladder neck. In 1995, Ulmsten and Petros described a rationale for a more distally placed suburethral sling based on concepts they termed the “integral theory.” This theory was based on the presumption that the pubourethral ligaments support the midurethra and attach to the pubic bones, acting as a backboard for the midurethra. This backboard allows the compression of the midurethra against it when intraabdominal pressure increases and maintains continence. The concept states that the absence of the backboard support causes a loss of this watertight seal, and SUI develops. By passing a strip of supportive material (loosely woven polypropylene) under the midurethra in women with SUI, this “backboard” action could theoretically be replicated. The strip of polypropylene was to be left loose or “tension-less,” and direct compression of the urethra was avoided. In its earliest configuration, placement of the MUS was achieved through an anterior vaginal wall dissection at the level of the midurethra. Placement of the sling material was accomplished by passage of the arms of the tape in a retropubic fashion through the anterior abdominal wall with the aid of specially designed trocars.

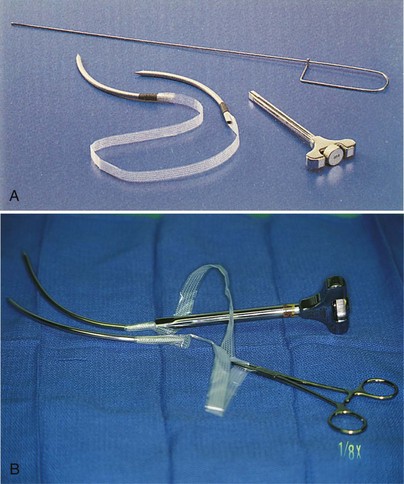

The first commercially available retropubic MUS was the tension-free vaginal tape (Gynecare, Somerville, NJ) (Figure 6-1), which consisted of a narrow polypropylene mesh strip with two specially designed trocars that were inserted through a small vaginal incision and passed through the retropubic space to an exit point in the suprapubic area of the anterior abdominal wall. Passage of the trocars from the vaginal incision to the anterior abdominal wall has been described as the “bottom-up” approach. Several other “kits” (Table 6-1) have also become available with minor modifications, including a “top-down” approach whereby the trocars are passed retropubically from the anterior abdominal wall to the vaginal incision, and the tape is attached to the vaginal end of the trocar and then pulled back up through the retropubic space to exit in the suprapubic area.

Table 6–1 Commercially available retropubic midurethral sling kits

| Sling | Manufacturer | Trocar Passage |

|---|---|---|

| TVT | Ethicon, Somerville, NJ | Bottom-up |

| SPARC Sling System | American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, MN | Top-down |

| LYNX Suprapubic MUS System | Boston Scientific, Natick, MA | Top-down |

| Advantage Fit System | Boston Scientific | Bottom-up |

| Align Retropubic | Band Medical, Covington, GA | Bottom-up and top-down |

Indications, Patient Selection, and Types of Slings

Other patients in whom a synthetic sling is probably inappropriate include patients who are undergoing concurrent or have undergone prior urethral reconstruction. Examples include urethral diverticulectomy, urethrovaginal fistula repair, or urethral injury secondary to prior sling placement or pelvic fracture. Although there are no reports of MUS being used in this setting, experience with synthetic material in the setting of urethral reconstruction has demonstrated a high rate of erosion (Morgan et al., 1985). In contrast, excellent outcomes have been reported with the use of a biologic pubovaginal sling in the setting of reconstruction, with an 88% cure rate after diverticulectomy in 16 patients and an 86% cure rate after genitourinary fistula repair in 7 patients, with no reported erosions (Carey et al., 2002). Also, a synthetic MUS is not recommended in patients with neurogenic incontinence, such as spina bifida, because they are already dependent on clean intermittent self-catheterization, and a tension-free MUS may not provide the necessary compression to achieve continence in between catheterizations. Biologic pubovaginal slings have been used successfully in patients with neurogenic causes of SUI, providing occlusion at the bladder neck, with continence rates in one study of 95% (Austin et al., 2001).

As previously mentioned, the initial TVT system was classified as a bottom-top technique. An alternative system called SPARC (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, MN) was developed a few years later with the passage of the trocar from the suprapubic region down into the vagina (top-down technique). A meta-analysis by Ogah et al. (2009) compared five randomized controlled trials of TVT versus SPARC and showed that the TVT had higher subjective and objective cure rates of 85% and 92% compared with 77% and 87% of SPARC. The same study showed significantly lower complication rates in the patients receiving TVT (less bladder perforation, mesh erosions, and voiding dysfunction). However, these findings have not been duplicated in other single arm series, which have demonstrated comparable efficacy and low complication rates with the top-down technique (SPARC). Table 6-1 lists the commercially available synthetic retropubic MUS.

Surgical Technique

Bottom-to-Top

1. Anesthesia. We prefer to use general anesthesia; however, some surgeons prefer intravenous sedation with local anesthesia to allow the performance of the cough stress test to facilitate appropriate tensioning of the sling. Because approximately 50% of cases are done in conjunction with a prolapse repair, all surgeons need to be well versed at tensioning techniques under general anesthesia (see Step 6).

2. Vaginal dissection. The anterior vaginal wall is hydrodistended with a combination of lidocaine and epinephrine, with the goal of completely blanching the anterior vaginal wall at the level of the mid- to distal urethra. A scalpel blade is used to make an incision from just below the external urethral meatus to the level of the midurethra. The vaginal wall is sharply dissected with Metzenbaum scissors off the posterior urethra, creating small tunnels to the inferior pubic ramus. Sharp dissection is required for this dissection because the distal anterior vaginal wall and posterior urethra are fused at this level (Figure 6-2). Some physicians prefer to hydrodissect the trocar trajectory bilaterally before passing the trocars.

3. Trocar passage. A catheter guide is placed in the indwelling Foley catheter so that the urethra and bladder neck can be displaced away from where the trocar is inserted. The trocar tip is inserted into the previously dissected tunnel on each side lateral to the urethra and advanced to the undersurface of the pubic bone. The tip of the trocar should be sandwiched between the index finger of the surgeon’s nondominant hand placed in the anterior vaginal fornix and the undersurface of the interior pubic ramus. The tip of the needle is carefully advanced through the endopelvic fascia into the retropubic space (Figure 6-3). When the resistance of the endopelvic fascia is overcome and the tip of the needle is in the retropubic space, the handle of the trocar is dropped, and the needle is advanced through the retropubic space as it hugs the back of the pubic bone (Figure 6-4). The next resistance felt is the rectus muscle and anterior abdominal fascia. The needle is advanced through these structures to exit through the previously made suprapubic stab wound (see Figure 6-4). Figures 6-5 and 6-6 illustrate the appropriate passage of the needle through the retropubic space when viewed from above.

4. Cystoscopy. Cystoscopy is performed with a 30- or 70-degree scope to evaluate the bladder for inadvertent trocar injury with the trocar in place. If such an injury were to occur, it would generally be visualized in the anterolateral aspect of the bladder (usually the area between 1 o’clock and 3 o’clock on the left side and 9 o’clock and 11 o’clock on the right side). If the trocar is seen or there is any creasing of the bladder mucosa that does not disappear with bladder distention, the trocar should be withdrawn and repassed. Most commonly when the bladder is perforated (which occurs in approximately 3% to 5% of cases), it is because the surgeon has allowed the trocar to migrate away from the back of the pubic bone in a cephalad direction (see Figure 6-5, A

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree