3 Surgical Anatomy of the Anterior Vaginal Wall, Retropubic Space, and Inner Groin

Anatomy of Anterior Vaginal Wall

When performing suburethral sling procedures for stress urinary incontinence, fully appreciating the relationship between the anterior vaginal wall and the posterior urethra and bladder becomes very important in regard to establishing appropriate planes of dissection (Video 3-1 ![]() ). Synthetic midurethral slings have become very popular for the correction of stress incontinence. These slings are placed in the distal to mid urethra; this dissection plane is a completely different dissection plane than the plane of dissection under the proximal urethra and bladder neck. The distal portion of the anterior vaginal wall is just superior to the perineal membrane and is fused with the posterior wall of the urethra. An appropriate dissection plane requires sharp dissection to elucidate fully the plane in which the sling is placed (see Video 3-1

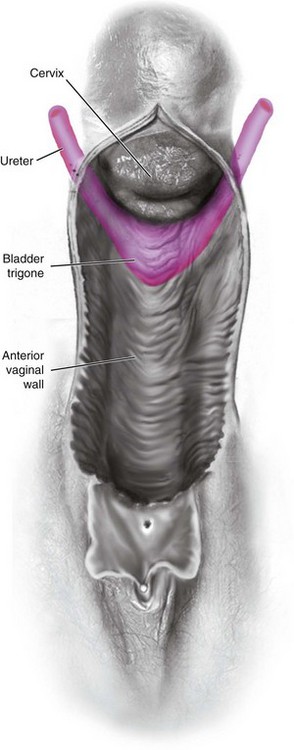

). Synthetic midurethral slings have become very popular for the correction of stress incontinence. These slings are placed in the distal to mid urethra; this dissection plane is a completely different dissection plane than the plane of dissection under the proximal urethra and bladder neck. The distal portion of the anterior vaginal wall is just superior to the perineal membrane and is fused with the posterior wall of the urethra. An appropriate dissection plane requires sharp dissection to elucidate fully the plane in which the sling is placed (see Video 3-1 ![]() ). As the dissection extends toward the bladder neck, there is a much clearer plane of dissection between the proximal urethra and the anterior vaginal wall and subsequently between the vaginal wall and the wall of the bladder. The vagina lies anteriorly adjacent to and supports the bladder base, from which it is separated by the vesicovaginal adventitia (endopelvic fascia). The urethra is fused with the anterior vagina, with no distinct adventitial layer separating them. The terminal portions of the ureters cross the lateral fornices of the vagina on their way to the bladder base (Figure 3-1). Dissection in the middle third of the anterior vaginal wall can be either superficial to the fibromuscular layer of the vagina, within the fibromuscular layer of the vagina, or deeper in the true vesicovaginal space. The dissection of the deeper vesicovaginal space separates the vaginal wall from the overlying trigone. In the authors’ opinion, the best dissection plan when performing a traditional anterior colporrhaphy is to be within the fibromuscular layer of the vagina because this plane is the least vascular and allows appropriate plication without significant distortion of the trigone or irritation of the visceral innervation of the bladder. If mesh augmentation is to be used, some surgeons believe that placing the mesh in the deeper vesicovaginal space decreases the chance for subsequent vaginal mesh erosion.

). As the dissection extends toward the bladder neck, there is a much clearer plane of dissection between the proximal urethra and the anterior vaginal wall and subsequently between the vaginal wall and the wall of the bladder. The vagina lies anteriorly adjacent to and supports the bladder base, from which it is separated by the vesicovaginal adventitia (endopelvic fascia). The urethra is fused with the anterior vagina, with no distinct adventitial layer separating them. The terminal portions of the ureters cross the lateral fornices of the vagina on their way to the bladder base (Figure 3-1). Dissection in the middle third of the anterior vaginal wall can be either superficial to the fibromuscular layer of the vagina, within the fibromuscular layer of the vagina, or deeper in the true vesicovaginal space. The dissection of the deeper vesicovaginal space separates the vaginal wall from the overlying trigone. In the authors’ opinion, the best dissection plan when performing a traditional anterior colporrhaphy is to be within the fibromuscular layer of the vagina because this plane is the least vascular and allows appropriate plication without significant distortion of the trigone or irritation of the visceral innervation of the bladder. If mesh augmentation is to be used, some surgeons believe that placing the mesh in the deeper vesicovaginal space decreases the chance for subsequent vaginal mesh erosion.

Anatomy of the Lower Urinary Tract

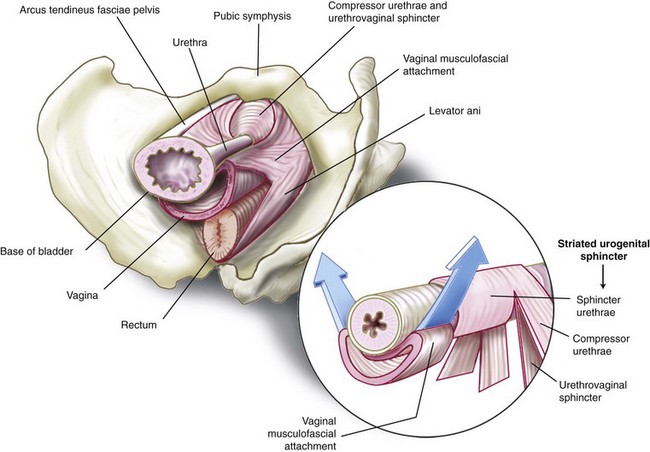

Traditionally, support of the urethra and bladder neck was thought to be provided by the interaction of the pubourethral ligaments, the perineal membrane, and the muscles of the pelvic floor. Milley and Nichols (1971) found bilaterally symmetric anterior, posterior, and intermediate pubourethral ligaments and stated that the anterior and posterior ligaments were formed by inferior and superior fascial layers of the perineal membrane. An anatomic defect of the pubourethral ligaments has been cited as a contributing factor to stress urinary incontinence and is thought to be in part (based on the integral theory of Ulmsten and Petros, 1995) why synthetic midurethral slings surgically correct stress incontinence. Studies by DeLancey (1986, 1988, 1989) showed that rather than being suspended ventrally by ligamentous structures, the proximal urethra and bladder base are supported in a slinglike fashion by the anterior vaginal wall, which is attached bilaterally to the levator ani muscles, at the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis. These attachments extend caudally and blend with the superior fibers of the perineal membrane. The tissues described as pubourethral ligaments are made up of the perineal membrane and the most caudal portion of the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis, which fix the distal urethra beneath the pubic bone. Figure 3-2 illustrates the anatomic structures that contribute to urethral support and closure. The attachment of the anterior vaginal wall at the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis may contribute to urethral closure by providing a stable base onto which the urethra is compressed with increases in intraabdominal pressure. These attachments are also responsible for the posterior movement of the vesical neck seen at the onset of micturition and for the elevation noted when the patient is instructed to perform a Kegel exercise or interrupt her urinary stream. Defects in these attachments result in urethral hypermobility and anterior vaginal wall prolapse.