4 Retropubic Operations for Stress Urinary Incontinence

Introduction

Historically, there were few data to differentiate one retropubic procedure from another. The three most studied and popular retropubic procedures were the Burch colposuspension, the Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz (MMK) procedure, and the paravaginal defect repair. I prefer the Burch colposuspension for urodynamic SUI with bladder neck hypermobility and adequate resting urethral sphincter function, and sometimes combine it with a paravaginal defect repair when the patient has stage 2 or 3 anterior vaginal prolapse or when a concurrent sacrocolpopexy is to be done. The surgical techniques described in this chapter are contemporary modifications of the original operations. Tanagho (1976) described the modified Burch colposuspension. The paravaginal defect repair was described by Richardson et al. (1981) and Shull and Baden (1989) (paravaginal repair) and by Turner-Warwick (1986) and Webster and Kreder (1990) (vaginal obturator shelf repair). Although less critically studied, the paravaginal defect repair, until more recently, was regionally popular and widely performed in the United States. The operations described do not represent one correct technique but a commonly used and proven method.

Indications for Retropubic Procedures

To diagnose urodynamic SUI, clinical and urodynamics (simple or complex) testing must be performed to evaluate bladder filling, storage, and emptying (see Chapter 2). Abnormalities of bladder-filling function, such as detrusor overactivity, can coexist with urethral sphincter incompetence in 30% of patients and may be associated with a lower cure rate after retropubic surgery.

Surgical Techniques

Operative Setup and General Entry into the Retropubic Space

1. The patient is supine, with the legs supported in a slightly abducted position, allowing the surgeon to operate with one hand in the vagina and the other in the retropubic space. The vagina, perineum, and abdomen are sterilely prepared and draped in a fashion that permits easy access to the lower abdomen and vagina.

2. A three-way 16F or 20F Foley catheter with a 20- to 30-mL balloon is inserted in a sterile fashion into the bladder and kept in the sterile field. The drainage port of the catheter is left to gravity drainage, and the irrigation port is connected to sterile water with or without blue dye.

3. One perioperative intravenous dose of an appropriate antibiotic should be given as prophylaxis against infection within 1 hour before the incision is made.

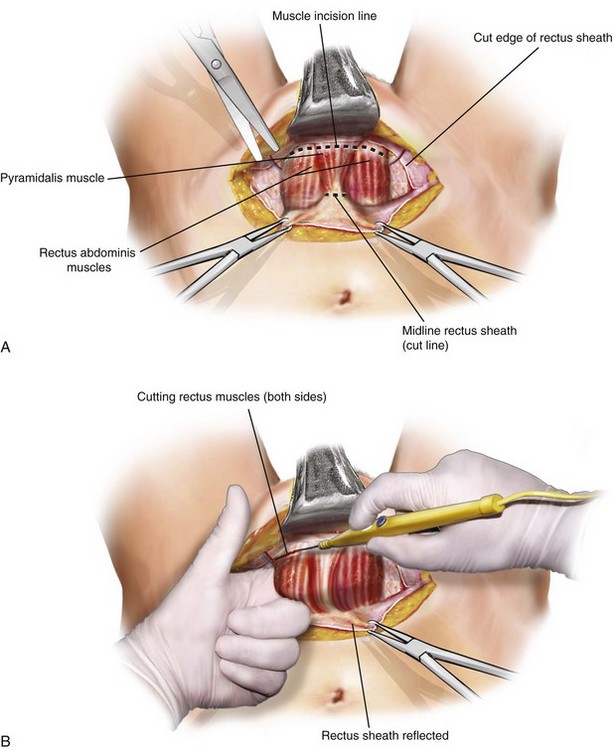

4. A Pfannenstiel incision is usually the preferred type of skin incision. Entrance into the retropubic space sometimes may be facilitated by using a Cherney incision (Figure 4-1). During intraperitoneal surgery, the peritoneum is opened, the surgery is completed, and the cul-de-sac is plicated, if necessary.

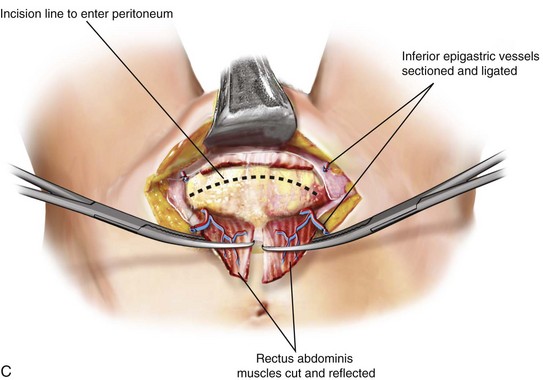

5. The retropubic space is exposed. Staying close to the back of the pubic bone, the surgeon’s hand is introduced into the retropubic space and the bladder and urethra are gently moved downward (Figure 4-2). Sharp dissection usually is not necessary in primary cases. To aid visualization of the bladder, 100 mL of sterile water with methylene blue or indigo carmine dye may be instilled into the bladder after the catheter drainage port is clamped.

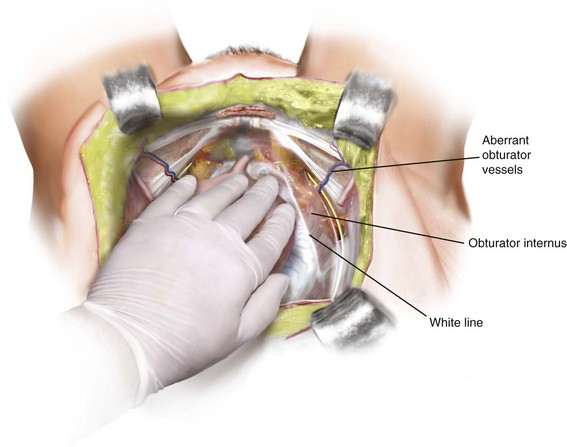

6. If previous retropubic or other bladder neck suspension procedures have been performed, dense adhesions from the anterior vaginal and bladder wall and urethra to the symphysis pubis are often present. These adhesions should be dissected sharply from the pubic bone until the anterior bladder wall, urethra, and vagina are free of adhesions and are mobile. If identification of the urethra or lower border of the bladder is difficult, one may perform a cystotomy, which, with a finger inside the bladder, helps to define the lower limits of the bladder for easier dissection, mobilization, and elevation (Figure 4-3).

Technique for Burch Colposuspension (Video 4-1  )

)

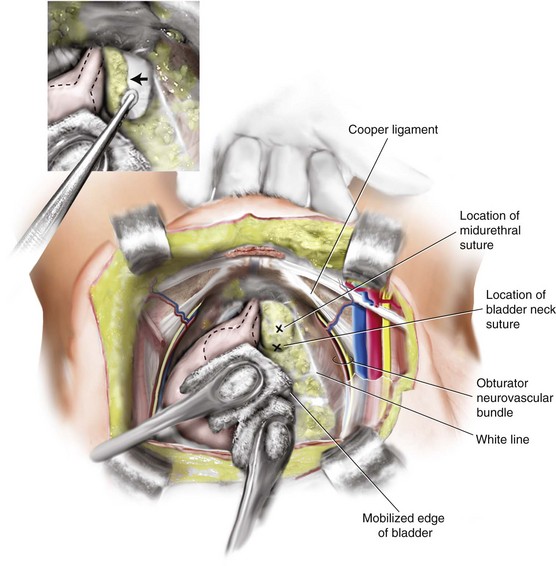

1. After the retropubic space is entered, the urethra and anterior vaginal wall are depressed. No dissection should be performed in the midline over the urethra or at the urethrovesical junction, protecting the delicate musculature of the urethra from surgical trauma. Attention is directed to the tissue on either side of the urethra. The surgeon’s nondominant hand is placed in the vagina, palm facing upward, with the index and middle fingers on each side of the proximal urethra. Most of the overlying fat should be cleared away, using a swab mounted on a curved forceps sponge stick. This dissection is accomplished with forceful elevation of the surgeon’s vaginal finger until glistening white periurethral fascia and vaginal wall are seen (Figure 4-4). This area is extremely vascular, with a rich, thin-walled venous plexus that should be avoided, if possible. The position of the urethra and the lower edge of the bladder is determined by palpating the Foley balloon and by partially distending the bladder to define the rounded lower margin of the bladder as it meets the anterior vaginal wall.

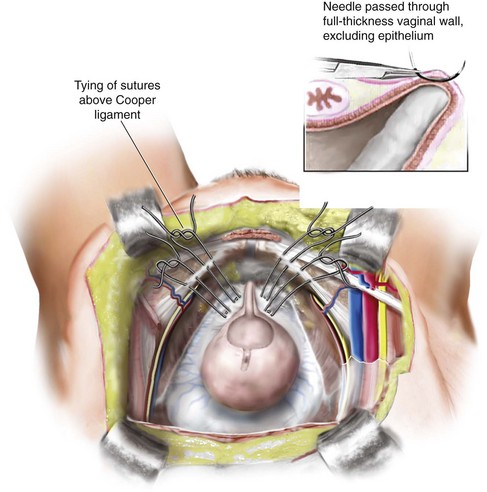

2. When dissection lateral to the urethra is completed and vaginal mobility is judged to be adequate by using the vaginal fingers to lift the anterior vaginal wall upward and forward, sutures are placed. No. 0 or 1 delayed absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures are placed as far laterally in the anterior vaginal wall as is technically possible. We apply two sutures of No. 0 braided polyester on an SH needle (Ethibond; Ethicon, Inc, Somerville, NJ) bilaterally, using double bites for each suture. The distal suture is placed approximately 2 cm lateral to the proximal third of the urethra. The proximal suture is placed approximately 2 cm lateral to the bladder wall at or slightly proximal to the level of the urethrovesical junction. In placing the sutures, one should take a full thickness of vaginal wall, excluding the epithelium, with the needle parallel to the urethra (Figure 4-5). This maneuver is best accomplished by suturing over the surgeon’s vaginal finger at the appropriate selected sites. On each side, after the two sutures are placed, they are passed through the pectineal (Cooper) ligament so that all four suture ends exit above the ligament. Before the sutures are tied, a 1 × 4 cm strip of absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) may be placed between the vagina and obturator fascia below the Cooper ligament to aid adherence and hemostasis.

3. As noted previously, this area is extremely vascular, and visible vessels should be avoided if possible. When excessive bleeding occurs, it can be controlled by direct pressure, sutures, or vascular clips. Less severe bleeding usually stops with direct pressure and after tying the suspension sutures.

4. After all four sutures are placed in the vagina and through the Cooper ligaments, the assistant ties first the distal sutures and then the proximal ones, while the surgeon elevates the vagina with the vaginal hand. In tying the sutures, one does not have to be concerned about whether the vaginal wall meets the Cooper ligament, so one should not place too much tension on the vaginal wall. A suture bridge is usually found between the two points. After the sutures are tied, one can easily insert two fingers between the pubic bone and the urethra, preventing compression of the urethra against the pubic bone. Vaginal fixation and urethral support depend more on fibrosis and scarring of periurethral and vaginal tissues over the obturator internus and levator fascia than on the suture material itself (see Video 6-1 ![]() ).

).

Paravaginal Defect Repair (Video 4-2  )

)

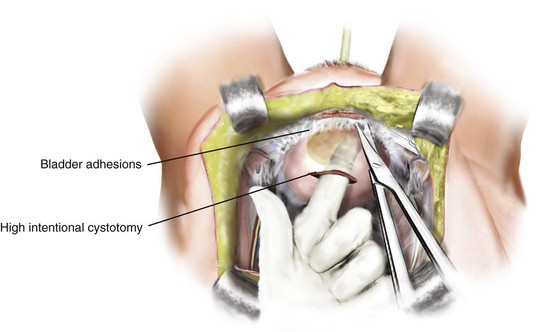

1. The retropubic space is entered, and the bladder and vagina are depressed and pulled medially to allow visualization of the lateral retropubic space, including the obturator internus and levator muscles, and the fossa containing the obturator neurovascular bundle.

2. Blunt dissection can be carried dorsally from this point until the ischial spine is palpated. The arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis is often visualized as a white band of tissue running over the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles from the back of the lower edge of the symphysis pubis toward the ischial spine. A lateral paravaginal defect representing avulsion of the vagina off the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis or of the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis off the obturator internus muscle may be visualized.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree