Repair of Bile Duct Stricture/Injury and Techniques for Accessing the Proximal Biliary Tree

Chad G. Ball

James J. Mezhir

William R. Jarnagin

Keith D. Lillemoe

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONSBile duct injuries are the most serious complication associated with cholecystectomy. The incidence of biliary injury has increased substantially in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Currently, data from large surveys of patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy suggest an incidence of 0.4% to 0.6%. Management of these injuries requires a multidisciplinary approach involving interventional radiology and endoscopy combined with experienced hepatobiliary surgeons. Although mortality is uncommon, these injuries remain a major source of patient morbidity and major hospital costs and negativity affect patients’ short-term quality of life.

Less than one-third of iatrogenic bile duct injuries are actually detected at the time of the cholecystectomy. The majority are therefore identified postoperatively, and in general, present in one of two forms: biliary leak with biloma formation or complete biliary obstruction. Most commonly, the hepatic duct has been transected and incompletely clipped resulting in bile leakage into the peritoneal cavity. These patients usually present 24 to 72 hours after cholecystectomy with increasing abdominal pain, distension, nausea, and evidence of early sepsis. Patients in whom the common hepatic duct has been completely clipped will present days to weeks after cholecystectomy with pain and jaundice, or less commonly pain and fever indicative of cholangitis. Any such atypical course from the routine recovery for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy should prompt an immediate evaluation for possible biliary injury.

The precise indications and contraindications for operative therapy of a bile duct injury/stricture are based on (1) the mode of injury, (2) the interval between the injury and its diagnosis, (3) the clinical condition of the patient, and (4) the local conditions inherent within the operative field.

The general strategy for managing the injury however involves avoiding immediate operative intervention to attempt definitive repair. If early laparotomy is performed in the face of sepsis continued uncontrolled bile leak or following complete transection of the common bile duct, marked inflammation in the operative field will obscure the area and make identification of the biliary system difficult. Biliary reconstruction under these circumstances is therefore a relative contraindication because it will be technically challenging and frequently end in long-term failure in the form of an anastomotic leak or biliary stricture. To avoid this outcome, early management involves less invasive measures to first define the anatomy of the injury, and then to control biliary sepsis or the ongoing bile leak. Definitive repair is carefully planned and undertaken weeks following the initial injury, well after periportal inflammation has been allowed to resolve. Delaying definitive repair also has the substantial advantage of allowing the clinician time to investigate for concurrent hepatic arterial vascular injury using arterial phase computed tomography (CTA). If there has been a concurrent arterial injury however, a delay will also allow the delineation of both the zone and level of ischemia. Early bile duct repair in the setting of an unrecognized hepatic arterial injury leads to a significantly higher stricture rate.

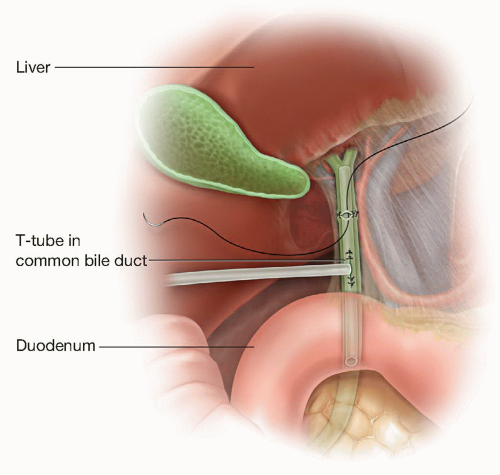

In cases in which the injury is actually recognized at the time of the cholecystectomy, an attempt at immediate repair is often warranted. The first step in this repair is an intraoperative cholangiogram, which will confirm and better define the injury and will help determine the most appropriate surgical management. If a small segmental duct (<3 mm in diameter) has been injured and cholangiography demonstrates segmental or subsegmental drainage by the injured system, simple ligation of the injured duct will be adequate treatment. If the injured duct is larger (4 mm in diameter) or provides sectoral or lobar drainage as demonstrated by the cholangiogram, surgical repair is required. If the injured segment of the bile duct is short (<1 cm) and two resultant viable ends can be opposed without tension, an end-to-end primary anastomosis is a reasonable strategy, recognizing, however, that late stricture rates are not insignificant. In this case, a generous Kocher maneuver will mobilize the duodenum out of the retroperitoneum and alleviate tension at the repair. The injured ends of the bile duct are debrided to healthy mucosa and a spatulated end-to-end repair is made using interrupted 5-0 monofilament absorbable suture. A T-tube should be placed below and not through the anastomosis (Fig. 17.1). For proximal injuries near the hepatic duct bifurcation or if the injured segment of the bile duct is longer than 1 cm, an end-to-end primary biliary anastomosis will result in excessive tension and should always be avoided in favor of a Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

Finally, if the circumstances of the procedure or the experience of the surgeon are such that an optimal repair is not possible, adequate drainage and transfer to a tertiary care biliary surgeon is advised.

Finally, if the circumstances of the procedure or the experience of the surgeon are such that an optimal repair is not possible, adequate drainage and transfer to a tertiary care biliary surgeon is advised.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

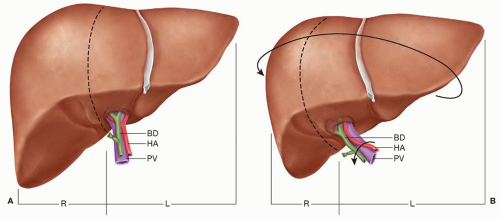

PREOPERATIVE PLANNINGPreoperative investigation and planning are of paramount importance to ensure a successful and durable bile duct repair. High quality cross-sectional imaging, typically a triple phase contrast-enhanced CT, is critical and will provide much of the necessary information regarding the extent of the problem, including areas of bile collection requiring drainage, the level of biliary obstruction, and associated vascular injuries. In addition, in patients with a complex history or a protracted course, imaging may show evidence of lobar atrophy (see Chapter 26) or cirrhosis. The former is more likely to arise in the setting of a combined biliary and vascular injury and has important technical implications for repair, related to rotational distortion of the porta hepatis structures (Fig. 17.2). Hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis can result from prolonged biliary obstruction and is typically encountered in patients with multiple failed attempts at repair over a prolonged period. While uncommon, cirrhosis is an ominous finding, usually an end stage event, and attempts at repair in this setting are associated with very high mortality rates.

In patients presenting early following cholecystectomy, the most common mode of presentation will be a bile leak. Significant right upper quadrant pain and fever will be evident days after the procedure (direct hyperbilirubinemia and leukocytosis). The diagnosis of bile leak is made by either CT or ultrasound. Every attempt is then made to first control the associated sepsis via nonoperative means and delay surgical intervention. Once the biloma is identified, it is drained percutaneously. Broad spectrum antibiotics with adequate biliary penetration are started and tailored to culture results. In most cases, simple drainage is adequate to control the infection. Unresolved sepsis should, however, prompt imaging assessment to ensure that the drain or drains are positioned adequately; in some cases multiple drainage catheters will be necessary, or in rare cases, percutaneous biliary drainage may be required to divert bile flow away from the area of injury.

Once adequate drainage is established, the next preoperative phase is defining the location of the leak (minor injury (an open cystic duct stump or open biliary radical in the gallbladder fossa (duct of Lushka)) versus major injury (right hepatic or common hepatic duct laceration)). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram (ERC) has the advantage of being less invasive than percutaneous cholangiography and, in the case of a minor leak, can provide definitive therapy. On the other hand, ERC will not define the proximal biliary tree when there has been transection of the bile duct. For cystic duct stump leaks and duct of Lushka leaks, a transampullary stent may facilitate biliary drainage through the sphincter of Oddi and may be enough to allow the patient to heal the leak, although the added benefit of this procedure above and beyond drainage of the biloma has not been shown. Major lacerations or complete transections to the common hepatic duct or right hepatic duct will not be amenable to endoscopic therapy and will ultimately require biliary-enteric anastomosis. Since ERC will usually identify the site of the injury but will not adequately define the proximal biliary anatomy, as clips are usually obstructing retrograde filling, a complete cholangiogram must be obtained with either MRC or percutaneous cholangiography. Obtaining a detailed outline of the proximal anatomy prior to definitive reconstruction is of paramount importance for preoperative planning.

Although the preoperative placement of a percutaneous biliary drain is controversial, many authors utilize this technique. These drains may (1) aid in the manual palpation/identification of the common bile duct at the time of exploration, and (2) simplify the placement of transhepatic catheters. If this approach is used, at least one small (7 to 10 French) biliary drain is placed as close to the site of the injury as possible. If the biliary injury is above the bifurcation of the bile ducts and definitive repair will require a double barrel reconstruction, two biliary drains should be placed: one in the left system and one in the right biliary system. The timing of the biliary drain placement is dictated by the degree of sepsis at presentation. If the sepsis or the ongoing leak can be controlled with subhepatic drains, percutaneous biliary drain placement is not required at the time of presentation and will only add risk of preoperative biliary sepsis. An MRC may be used to define the anatomy and the biliary drain is placed immediately prior the definitive repair. If subhepatic drains do not control the biliary sepsis or the bile leak, the biliary drainage catheters may be required at the time of presentation.

As a result, comprehensive preoperative planning for major bile duct injuries requires:

Complete control/evacuation of peritoneal sepsis and bile

Accurate definition of the site of the injury (ERC)

Complete identification of the proximal biliary anatomy (MRC or PTC)

Placement of percutaneous biliary catheter/drain(s) (PTD) in selected patients

In patients who present with biliary stricture or complete obstruction of some element of the biliary system days to weeks after cholecystectomy, the overall strategy is similar. For patients with a stricture and symptoms of cholangitis, biliary decompression should be performed and is usually best accomplished with by transhepatic percutaneous catheter placement. In selected cases, endoscopic biliary stents can be places to decompress the proximal biliary system. In these situations nonoperative balloon dilation with long-term stenting is an option for management.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

SURGICAL TECHNIQUEThe goal of operative management for any biliary injury is the reestablishment of bile flow into the proximal gastrointestinal tract in a manner that prevents sludge, stone formation, cholangitis, stricture and cirrhosis related to prolonged biliary obstruction. Invariably, there is loss of bile duct length as a result of periductal fibrosis associated with the injury, and simple excision of a bile duct stricture with end-to-end ductal anastomosis or repair is rarely technically feasible and frequently unsuccessful even if

possible. Consequently, principles for a successful biliary-enteric (Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy) reconstruction include:

possible. Consequently, principles for a successful biliary-enteric (Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy) reconstruction include:

Exposure of healthy proximal bile duct that provides drainage of the entire liver

Preparation of a suitable section of intestine that can be anastomosed without tension

Creation of a biliary-enteric anastomosis that approximates healthy biliary mucosa to enteric mucosa

Positioning and Incision

A midline upper abdominal or extended right subcortal incision in a supine patient provides adequate access. A fixed upper abdominal retraction system (i.e., Thompson) is utilized (see Figs. 18.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree