Rectal prolapse is best diagnosed by physical examination and by having the patient strain as if to defecate; a laparoscopic rectopexy is the preferred treatment approach. Intussusception is more an epiphenomena than a defecatory disorder and should be managed conservatively. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome is a consequence of chronic straining and therapy should be aimed at restoring a normal bowel habit with behavioral approaches including biofeedback therapy. Rectocele correction may be considered if it can be definitively established that it is a cause of defecation disorder and only after conservative measures have failed. An enterocele should only be operated when pain and heaviness are predominant symptoms and it is refractory to conservative therapy.

Rectal prolapse, intussusception (occult rectal prolapse), solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS), and rectocele are common pelvic floor disorders that share many clinical features and have a common pathogenesis. Chronic constipation, especially an evacuation disorder, is often an underlying problem that leads to these abnormalities. For example, chronic straining may cause intussusception of the rectal mucosa, which subsequently can develop into a full-thickness rectal prolapse. A prolapse may cause excessive stretching of the rectal mucosa that can lead to mucosal injury and cause a rectal ulcer. Furthermore, chronic straining and difficulty with evacuation may induce a rectocele. Because these problems are interrelated, an integrated multidisciplinary approach is required for their management.

Rectal prolapse

Definition, Etiology, and Pathogenesis

A complete rectal prolapse is defined as the protrusion of all layers of the rectal wall through the anal canal. If the rectal wall prolapses but does not protrude through the anus it is called an “occult rectal prolapse” or a “rectal intussusception.” A rectal prolapse should be distinguished from a mucosal prolapse; in the latter there is only protrusion of the rectal or anal mucosa. The incidence of rectal prolapse is approximately 2.5 per 100,000 inhabitants, with a highest incidence among elderly women. In adolescents, the gender ratio is equal.

In the elderly patient with a rectal prolapse both a weak pelvic floor and a mobile rectum are present. Straining over many years (caused by longstanding constipation) is believed gradually to weaken the pelvic floor causing pudendal nerve damage, and this in turn may lead to weakness of the internal and external anal sphincters. These pathophysiologic changes facilitate protrusion of the rectal wall through the anus. Furthermore, pudendal neuropathy caused by either aging or obstetric injury may play a role.

There are two theories regarding the development of rectal prolapse. In 1912, Moschcovitz proposed that a deep pouch of Douglas may allow the small bowel to protrude into the lower anterior rectal wall. This protrusion together with a mobile mesorectum and mesosigmoid may allow the development of a rectal prolapse. In 1968, Broden and Snellman used cinematography and suggested that intussusception from the rectosigmoid region was the main cause.

Symptomatology

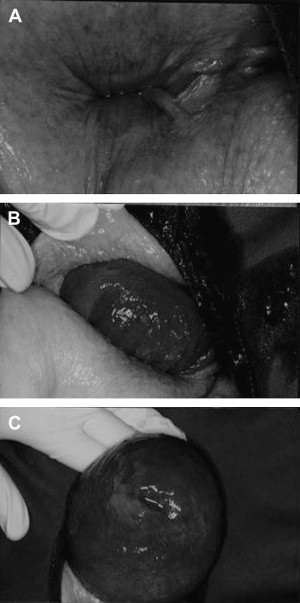

The most common complaint is a protrusion of the rectum through the anus, usually no greater than 15 cm ( Fig. 1 ). The rectum is often edematous with a fragile mucosa and small ulcerations. It is always possible to push back the prolapse, unless there is strangulation. Passage of mucus and blood is common. Fecal incontinence is associated with rectal prolapse in 20% to 100% of patients, depending on the patient’s age. These patients have a very weak pelvic floor with low external anal sphincter pressures. Constipation is common and is found in up to 70% of patients with rectal prolapse. Pre-existing dysmotility, dyssynergic defecation, or intussusception are also possible predisposing factors.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made by inspecting the perineum while asking the patient to strain as if to defecate. If the prolapse cannot be evoked on the examination table, the patient is asked to strain in the lavatory. The upright position and privacy are often helpful. Although additional tests are available, they play little role in the patient’s management, but provide insights into the pathophysiology and are useful for research purposes.

Imaging Investigations

Defecography can demonstrate prolapse through the anus, but is not necessary for demonstrating a full-thickness rectal prolapse. The anorectal angle is often obtuse in patients with a rectal prolapse, especially in those with coexisting fecal incontinence. In addition many other features seen with obstructed defecation, such as rectocele, sigmoidocele, or enterocele, may coexist.

Anal endosonography may show asymmetry and thickening of the internal anal sphincter and submucosa. Demonstration of a sphincter defect can be useful if a sphincter reconstruction is being considered.

Anorectal Function Tests

Anal manometry shows low resting pressure and patients with coexisting fecal incontinence have low squeeze pressures. After surgery, either there is no change or improvement of the resting pressure and sometimes the sphincter length. Squeeze pressure may also improve. The rectoanal inhibitory reflex may also improve after rectopexy. These changes may be caused by cessation of constant dilatation of the internal sphincter by the prolapsed rectum.

Rectal sensitivity and compliance measurements have demonstrated a normal maximal tolerable volume and pressure. After rectopexy, the rectal pressure at maximal tolerable volume increased significantly and the compliance decreased. Biomechanics and visceroperception show diminished rectal sensitivity and compliance. Anal sensitivity is also diminished in patients with rectal prolapse and remains unaltered after surgery.

Electromyography has provided insights into the pathogenesis of fecal incontinence but has no place in clinical work-up and hardly any in research. Abnormalities can be found in patients with a rectal prolapse, but these results do not predict continence after rectopexy. Another study found that injury to the pudendal nerve may be responsible for postoperative incontinence, but this was not confirmed in two other studies.

Colonic transit time has been shown to be prolonged before surgery. Furthermore, patients with rectal prolapse have an abnormal motility associated with reduced high-amplitude propagated contractions. Colonic transit time performed before and after a Ripstein rectopexy showed a delayed transit postoperatively.

Treatment

Correction of rectal prolapse is surgical, but how this should be done is reflected in the following remark of Charles Wells in 1959: “I have traced in the literature between 30 and 50 operations for prolapse in the rectum and would like to add still one more”. The traditional treatment for complete rectal prolapse consists of either transabdominal or perineal approaches. The parameters used to assess the success of surgery are the improvement of incontinence and constipation, and a low recurrence rate. Until recently, abdominal rectopexy, with or without high anterior resection, has been advocated as the treatment of choice for complete rectal prolapse. Because most patients are elderly and are not always fit to undergo an abdominal procedure, various perineal approaches, such as Delorme’s procedure or perineal proctosigmoidectomy, have been recommended in the past. Two developments have changed this attitude in the last few years: the introduction of the laparoscopic approach; and the need to consider, because of the frequent association of an enterocele or genital prolapse with the rectal prolapse, some form of obliteration of the Douglas space or colpopexy along with the rectopexy. In a recent meta-analysis that compared the open with the laparoscopic rectopexy both were equally efficacious with regards to the recurrence, morbidity, and length of stay. The laparoscopic approach by minimizing the operative trauma has almost superceded the open approach and can be considered suitable for the elderly population. In many it can be combined with other procedures, such as colpopexy and eventually anterior resection. In this way, perineal operations are only indicated in high-risk groups of patients.

Surgical Technique

Abdominal rectopexy

All classical abdominal procedures, such as the Ripstein-Wells operation, imply different grades of rectal mobilization, with or without anterior resection of the rectum followed by fixation of the rectum to the promontory (rectopexy). Nowadays, laparoscopic approach is the choice for most surgeons for this abdominal fixation, even though it is unclear which procedure is ideal: the posterior rectopexy or the laparoscopic ventral recto(colpo)pexy.

Patients are prepared by giving mechanical bowel preparation and prophylactic antibiotics. The bladder should be emptied before the start of the operation by introducing a catheter.

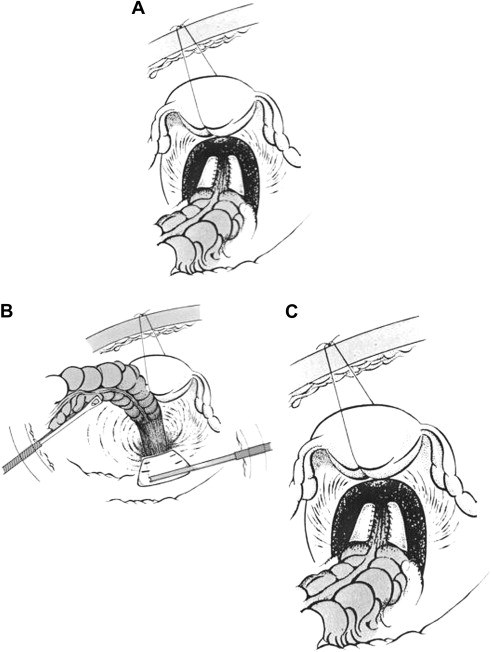

Modified ripstein procedure by laparoscopic approach

The patient is placed in the supine position on a short “bean bag” with the legs held in leg rests, to facilitate the inspection and digital examination during surgery. The patient is placed in a steep Trendelenburg’s position. A four-port technique, placed in the lower abdomen, is used. The 30-degree laparoscope is introduced under the umbilicus, a 12-mm port at the right lower quadrant, another 5-mm port right lateral of the umbilicus, and finally another 5-mm port in the left lower quadrant. If present, the uterus is fixed to the ventral abdominal wall using a temporary suture ( Fig. 2 A ). The rectum is subsequently mobilized taking care to identify the left ureter and the hypogastric nerves. Anteriorly, the rectum is mobilized up to the upper limit of the vagina; posteriorly, the presacral space is entered and dissected up to the level of the coccyx. The lateral ligaments and nervi erigentes are left intact ( Fig. 2 B).

The fixation can be achieved by sutures or by mesh and the fixation can be combined, if indicated, with a high anterior resection. If mesh is used, this is tightly rolled and introduced into the abdomen and attached at the promontory to the presacral fascia using an endoscopic hernia stapler device or nonreabsorbable sutures. Subsequently, the rectum is held without tension, (paying attention that the prolapse is completely reduced) and fixed to the mesh by means of nonabsorbable sutures to the anterolateral wall of the rectum on each side, so that one third of the anterior rectal circumference is left free ( Fig. 2 C).

Laparoscopic ventral(colpo)pexy for rectal prolapse and enterocele

D’Hoore and Penninckx described the technique as follows.

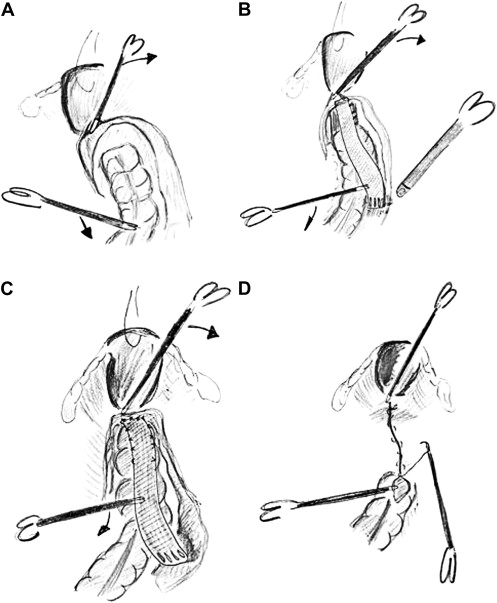

Step 1: dissection

After retraction of the rectosigmoid a left peritoneal incision is made over the sacral promontory and extended along the rectum up to the deepest point of Douglas and to the left. Lateral ligaments and right hypogastric nerve are left intact. Rectovaginal septum is broadly opened down to the pelvic floor after probing the vagina to facilitate this maneuver ( Fig. 3 A ). Lateral and posterior dissection is avoided, leaving lateral ligaments intact. If the pouch of Douglas is redundant, as in enterocele, the peritoneum is resected. Care is taken to avoid perforation of the rectum during the dissection.

Step 2: mesh fixation

A strip of Marlex trimmed to 3 × 17 cm is introduced in the abdomen. The mesh is sutured by means of nonabsorbable sutures to the ventral aspect and both sides of the lateral border of the distal rectum. The mesh is fixed to the sacral promontory using either sutures or an endofascia stapler (Endopath EMS, Johnson and Johnson; C.R. Bard, Inc., Billerica, Massachusetts) ( Fig. 3 B). The prolapse is reduced at the time of mesh fixation.

Step 3: vaginal fornix fixation

Posterior vaginal fornix is elevated and sutured to the same strip of mesh. If no enterocele is present, two sutures on the lateral aspect are sufficient. In other cases more sutures are placed. In this way a vaginal vault prolapse (middle pelvic compartment) and the enterocele are corrected ( Fig. 3 C).

Step 4: Neo-Douglas formation

Next, the lateral borders of the incised peritoneum are closed over the mesh using nonabsorbable sutures. This elevates the neo-Douglas over the colpopexy. The mesh should be covered with peritoneum to avoid fixation (or fistula formation) of the small bowel ( Fig. 3 D).

Perineal procedures

The two most commonly used perineal procedures are the perineal proctosigmoidectomy according to Altemeier and the Delorme procedure.

In the proctosigmoidectomy (Altmeier), the prolapsed rectum is held under gentle traction and is resected from below, taking care that at least 1 cm of rectum is left proximal to the dentate line to perform a coloanal anastomosis. The intervention procedure may be facilitated by the use of mechanical stapling devices.

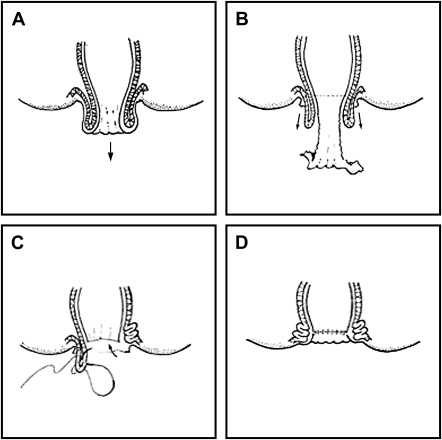

In the Delorme procedure, the mucosa is removed from the prolapsed rectum after submucosal injection of epinephrine 1 per 200,000 to avoid unnecessary bleeding. The mucosal stripping is performed by using a circumferential incision, up to 1 cm proximal to the dentate line. After removal of the mucosa from the prolapsed rectum, multiple longitudinal sutures are placed over the exposed muscularis, shortening the rectum and producing an accordion-like effect like a thick muscular ring. Afterward, the remaining mucosal ends are anastomosed with interrupted stitches of absorbable material ( Fig. 4 ).

Results

Elderly patients and a longer duration of follow-up are associated with less favorable outcome and a higher recurrence rate. Recurrence rates for different rectopexy techniques are low (0%–8%), although all of these procedures increase risk of constipation (up to 50%). The combination of resection with any form of rectopexy decreases constipation in almost 75% of patients. Perineal procedures have recurrence rates varying from 5% to 21% with no difference in incidence of constipation.

Recently, laparoscopic rectopexy has been developed as an alternative to the previously mentioned approaches, and many surgeons regard this as the standard approach for patients with rectal prolapse. This method combines the good functional outcome of abdominal procedures with the low postoperative morbidity of the minimally invasive surgery.

In 28 consecutive laparoscopic operations in the authors’ center using a modified Ripstein procedure, only two partial recurrences were seen (7%). Continence improved significantly in 76%; 14% developed mild constipation postoperatively and responded to a high-fiber diet and bulk agents.

After an abdominal rectopexy, most patients (50%–88%) show improvement in fecal incontinence, but after the perineal procedure incontinence rates are higher. In the authors’ series and others, the return of continence was associated with a small but significant increase in basal sphincter pressure, recovery of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex, and normalization of the internal anal sphincter thickness. This suggests that restoration of internal anal sphincter function plays an important role, and this improvement may be caused by cessation of rectoanal inhibition, previously induced by the prolapsed bowel, or improved anal canal sensation.

A major drawback of abdominal rectopexy is constipation. Interestingly, both an improvement of constipation in 76% of patients and an increase in up to 56% of patients has been reported. Colonic denervation resulting in dysmotility and rectal denervation caused by dissection or division of the lateral ligaments and posterior dissection may in part be responsible. Preservation of lateral ligaments was associated with improvement of continence and reduction of constipation. This is reaffirmed by the finding that the rectal sensitivity, which has been proved to be impaired after lateral ligament division, was not changed significantly in patients after the operation. The addition of anterior resection to rectopexy is a common surgical treatment for rectal prolapse in a patient with constipation, but this approach is controversial. Important development is the anterior fixation of the rectum in the ventral recto(colpo)pexy. Rectal prolapse is associated with an enterocele in 40% of patients, but also with different grades of prolapse. Simultaneous obliteration of the deep Douglas space may help prevent symptoms of obstructed defecation. Furthermore, anterior position of the mesh allows colpopexy or vaginal vault fixation and provides permanent support for the neo-Douglas and middle pelvic compartment, and avoids any posterolateral dissection of the rectum and ligaments, improving continence and preventing constipation. The low morbidity (7%), reduced recurrence of 3% to 6%, improved continence in 90%, and resolution of constipation in 84% makes this the preferred operation for these patients.

Predicting the outcome of surgery

The results of preoperative manometry do not predict the functional outcome regarding continence, although patients with very low sphincter pressures have a poor prognosis. Also, electromyogram abnormalities and prolonged pudendal nerve latency did not predict the risk of postoperative incontinence except in one study.

There is a weak correlation between postoperative increased transit time and postoperative emptying difficulties. Division of the lateral ligaments may be related to postoperative constipation.

Postoperative Biofeedback

Postoperative biofeedback can improve external anal sphincter function. In these groups, however, the most important predictor of fecal incontinence was a low internal anal sphincter pressure, an abnormality that cannot be corrected with biofeedback.

Summary

Laparoscopic rectopexy, together with some form of fixation of the middle compartment, offers the best functional results in patients with rectal prolapse and vaginal vault prolapse.

Rectal intussusception

Definition, Etiology, and Pathogenesis

Rectal intussusception, occult rectal prolapse, or internal procidentia is an intussusception of the rectal wall that does not protrude through the anus and can be classified into high-grade (intrarectal) and low-grade (intra-anal) intussusception based on the level of mucosa protruding. Although it is associated with solitary rectal ulcer, rectal prolapse, or perineal descent, the finding per se is not pathologic. In 50% to 60% of healthy volunteers a rectal intussusception can be demonstrated. The rectal intussusception in patients with evacuatory dysfunction is more advanced morpholically, however, than that seen in asymptomatic controls. An intussusception seldom leads to total rectal prolapse. Today, many regard this condition as a consequence of dyssynergic defecation rather than a cause of the problem.

Symptomatology

Patients with high intussusception report feelings of obstructed defecation and incomplete evacuation, although many are asymptomatic. Depending on concurrent problems, such as rectocele, SRUS, pudendal neuropathy, or sphincter damage, additional symptoms, such as soiling, blood loss, or fecal incontinence, may occur. Studies have shown that the presence of an intussusception does not correlate with rectal emptying. Care must be taken when associating symptoms with rectal intussusception.

Diagnosis

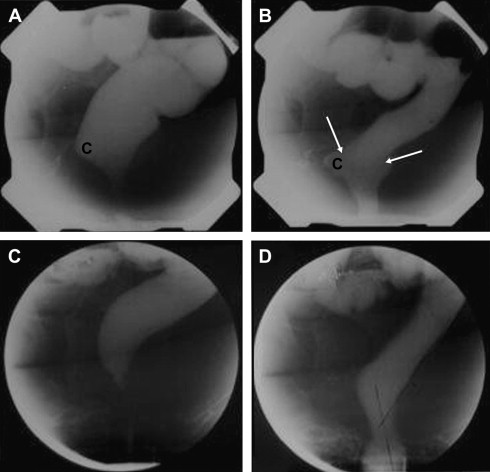

Defecography remains the standard for establishing this diagnosis ( Fig. 5 A , B). Sometimes the diagnosis can be made by rectal examination, but in one study an intussusception was palpable in only one third of patients. Even with defecography it can be difficult to distinguish rectal intussusception from normal rectal mucosal folds. Newer techniques, such as dynamic three-dimensional CT and (three-dimensional dynamic) anorectal ultrasonography, can also be of value. Dynamic MRI can also demonstrate an enterocele, although the lying position and costs are limitations.

Treatment

Conservative treatment aimed at restoring normal defecation is the first line of treatment. A fiber-enriched diet with additional fiber supplementation and sometimes laxatives may be useful. The next step is biofeedback to restore a normal defecation pattern; this has favorable results. In a study of 34 patients, 52% had complete resolution or improvement of symptoms. Concomitant fecal incontinence also improved. Long-term complaints of more than 9 years had a poor prognosis.

The role of surgical treatment for rectal intussusception is controversial. A Ripstein rectopexy has been performed and incontinence may improve but constipation generally worsens. Unlike patients with a rectal prolapse, there was no improvement in anal pressures. Preoperative diarrhea, fecal incontinence, and descending perineum syndrome and proximal intussusception are associated with a poor prognosis. Only a few patients with obstructive defecation improve, although the intussusception has disappeared ( Fig. 5 C, D), indicating that rectal invagination is a consequence of obstructed defecation. Hence, surgery should be avoided. Some patients develop additional complaints of tenesmus and increased defecation frequency or increased straining. Delorme’s transrectal excision is an alternative procedure and (laparoscopic) resection rectopexy is a new procedure that claims better results, but many failures occur. Hence, an intussusception should be considered an epiphenomena and treated conservatively. Surgery should be restricted to highly selected cases with a large intussusception; concomitant resection of part of the rectum (sigmoid) seems the best option.

Rectal intussusception

Definition, Etiology, and Pathogenesis

Rectal intussusception, occult rectal prolapse, or internal procidentia is an intussusception of the rectal wall that does not protrude through the anus and can be classified into high-grade (intrarectal) and low-grade (intra-anal) intussusception based on the level of mucosa protruding. Although it is associated with solitary rectal ulcer, rectal prolapse, or perineal descent, the finding per se is not pathologic. In 50% to 60% of healthy volunteers a rectal intussusception can be demonstrated. The rectal intussusception in patients with evacuatory dysfunction is more advanced morpholically, however, than that seen in asymptomatic controls. An intussusception seldom leads to total rectal prolapse. Today, many regard this condition as a consequence of dyssynergic defecation rather than a cause of the problem.

Symptomatology

Patients with high intussusception report feelings of obstructed defecation and incomplete evacuation, although many are asymptomatic. Depending on concurrent problems, such as rectocele, SRUS, pudendal neuropathy, or sphincter damage, additional symptoms, such as soiling, blood loss, or fecal incontinence, may occur. Studies have shown that the presence of an intussusception does not correlate with rectal emptying. Care must be taken when associating symptoms with rectal intussusception.

Diagnosis

Defecography remains the standard for establishing this diagnosis ( Fig. 5 A , B). Sometimes the diagnosis can be made by rectal examination, but in one study an intussusception was palpable in only one third of patients. Even with defecography it can be difficult to distinguish rectal intussusception from normal rectal mucosal folds. Newer techniques, such as dynamic three-dimensional CT and (three-dimensional dynamic) anorectal ultrasonography, can also be of value. Dynamic MRI can also demonstrate an enterocele, although the lying position and costs are limitations.

Treatment

Conservative treatment aimed at restoring normal defecation is the first line of treatment. A fiber-enriched diet with additional fiber supplementation and sometimes laxatives may be useful. The next step is biofeedback to restore a normal defecation pattern; this has favorable results. In a study of 34 patients, 52% had complete resolution or improvement of symptoms. Concomitant fecal incontinence also improved. Long-term complaints of more than 9 years had a poor prognosis.

The role of surgical treatment for rectal intussusception is controversial. A Ripstein rectopexy has been performed and incontinence may improve but constipation generally worsens. Unlike patients with a rectal prolapse, there was no improvement in anal pressures. Preoperative diarrhea, fecal incontinence, and descending perineum syndrome and proximal intussusception are associated with a poor prognosis. Only a few patients with obstructive defecation improve, although the intussusception has disappeared ( Fig. 5 C, D), indicating that rectal invagination is a consequence of obstructed defecation. Hence, surgery should be avoided. Some patients develop additional complaints of tenesmus and increased defecation frequency or increased straining. Delorme’s transrectal excision is an alternative procedure and (laparoscopic) resection rectopexy is a new procedure that claims better results, but many failures occur. Hence, an intussusception should be considered an epiphenomena and treated conservatively. Surgery should be restricted to highly selected cases with a large intussusception; concomitant resection of part of the rectum (sigmoid) seems the best option.

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

Definition, Etiology, and Pathogenesis

SRUS was first described in 1830 by Cruveilhier, but was recognized as a clinical entity in 1969 by Madigan and Morson. The estimated annual incidence is 1 to 3.6 per 100,000. About 80% of patients are less than 50 years. Gender distribution is either equal or there is a slight female preponderance. The mean age of presentation is 49 years, and about 25% present after 60 years. The condition is associated with an evacuation disorder. Defecography has shown that an intussusception is often present and evacuation is delayed. Ulceration is thought to occur during forceful straining against an immobile or a nonrelaxing pelvic floor (anismus).

Symptomatology

The classical symptoms of SRUS are rectal bleeding, passage of mucus, rectal pain, excessive straining, and tenesmus. Constipation is present in about 55% of patients. Many patients need digital assistance to defecate but do not admit this. Diarrhea is seen in 20% to 40% of patients. About 25% of patients have no complaints. The median time between presentation and diagnosis varies between 3 months to 30 years. Retrospective analysis has demonstrated that 26% of patients with SRUS are misdiagnosed initially and treated for inflammatory bowel disease. Rarely, massive hemorrhage can occur. In some patients, an underlying psychologic disorder, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, may be present.

Diagnosis

Sigmoidoscopy with rectal biopsy is diagnostic. The macroscopic appearance of the typical SRUS ulcer is a small, shallow lesion with a white slough or a hyperemic mucosal wall, usually on the anterior wall of the rectum ( Fig. 6 A ). Ulceration is present in about 57%. Polypoid lesions are found in about 25%. Patches of hyperemic mucosa are found in 18%. Lesions are multiple in 30%. SRUS is usually found on the anterior or anterolateral wall of the rectum, centered on a rectal fold. The distance from the anus is about 5 to 10 cm.