Constipation caused by dyssynergic defecation is common and affects up to one half of patients with this disorder. It is possible to diagnose this problem through history, prospective stool diaries, and anorectal physiologic tests. Randomized controlled trials have now established that biofeedback therapy is not only efficacious but superior to other modalities and that the symptom improvement is caused by a change in underlying pathophysiology. Development of userfriendly approaches to biofeedback therapy and use of home biofeedback programs will significantly enhance the adoption of this treatment by gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons.

Neuromuscular dysfunction of the defecation unit can lead to disordered or difficult defecation. Likewise, neuromuscular dysfunction of the colon may lead to slow transit constipation. In many patients there is an overlap, because colonic transit is delayed in two thirds of patients with difficult defecation. Preston and Lennard-Jones first described the association of paradoxical anal contraction during attempted defecation in patients with constipation and coined the term “anismus.” They believed that this condition was a spastic dysfunction of the anus, analogous to “vaginismus.” The term “anismus” implies a psychogenic etiology, however, which is not true although psychologic dysfunction has been described in these patients. In the literature, a number of terms have been used to describe the constipation that is associated with anorectal dysfunction, which includes anismus, pelvic floor dyssynergia, obstructive defecation, paradoxical puborectalis contraction, pelvic outlet obstruction, and spastic pelvic floor syndrome. Pelvic floor is a complex muscular apparatus that serves three important functions: (1) defecation, (2) micturition, and (3) sexual function. All-encompassing terms, such as “pelvic floor dyssynergia” or “pelvic outlet obstruction,” imply that this problem affects most of the pelvic floor, and possibly all of its functions. Although, some overlap has been described among patients with urinary obstruction and constipation, most constipated patients do not report sexual or urinary symptoms. Consequently, it misrepresents a functional disorder. Hence, these terms are not suitable. A consensus report from an international group of experts has recommended that the term “dyssynergic defecation” most aptly describes this form of constipation.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of chronic constipation varies from 2% to 28%. It is commonly encountered in primary care. Telephone interviews with 10,018 individuals, aged at least 18 years, produced an estimated prevalence of 14.7%. In a questionnaire survey of 5430 households across the United States, functional constipation was reported by 3.6% of responders and difficult defecation by 13.8%. Because most patients do not seek health care, its prevalence has been underestimated.

Constipation is more common in women with an estimated female/male ratio of 2.2:1. Its prevalence increases with advancing age, particularly after age 65, with the elderly reporting more problems with straining and hard stools than infrequency. Its prevalence is twofold higher in African Americans; in those of lower socioeconomic status (annual income ≤$20,000); and in nursing home residents. Pregnancy is also associated with higher prevalence of constipation, but no differences were seen between the first and the last trimester.

Economic and Social Impact

Chronic constipation has a significant impact on the use of health care resources, including the cost of inpatient and outpatient care, laboratory tests, and diagnostic procedures. In a recent study of 76,854 patients enrolled in Medical program, the total health care expenditure for patients with constipation over a 15-month period was $18,891,008, with an average cost of $246 per patient. Approximately 0.6% of patients were hospitalized with an average cost of $2993 per admission. In another study, expenditure for constipation was estimated at $235 million per year with 55% incurred from inpatient, 23% from emergency department, and 22% from outpatient care.

Psychologic Distress, Abuse, and Impact on Quality of Life

Constipation is associated with increased psychologic distress. Several studies have shown higher prevalence for anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsiveness, psychoticism, and somatization. Furthermore, paranoid ideation and hostility subscores were higher in patients with dyssynergia than slow transit constipation or healthy controls, providing evidence for significant psychologic distress, more so in dyssynergics than slow transit constipation patients.

Sexual abuse was reported by 22% to 48% of subjects, mostly women, whereas physical abuse was reported by 31% to 74% of constipated subjects. Another study found greater incidence of sexual abuse in women with pelvic floor dyssynergia. Also, patients with abuse were more likely to seek health care and report feelings of incomplete evacuation or urge to defecate, but did not demonstrate rectal hypersensitivity.

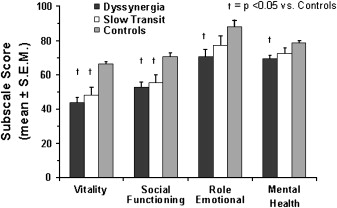

Patients with chronic constipation also showed significant impairment of health-related quality of life ( Fig. 1 ). Some domains were more affected in dyssynergics than slow transit constipation, suggesting that dyssynergia is associated with greater impact on quality of life. Also, psychologic distress and lower quality of life were strongly correlated suggesting that these dysfunctions have synergistic effects on bowel function.

Etiology and pathophysiology

Origin

How, when, and why an individual develops dyssynergic defecation is unclear. The authors’ prospective survey of 100 patients with dyssynergic suggested that the problem began during childhood in 31% of patients; after a particular event, such as pregnancy, trauma, or back injury in 29% of patients; and no identifiable precipitating cause in 40% of patients. Two thirds acquire this condition during adulthood. In this group, 17% reported a history of sexual abuse, 43% the passage of hard stools frequently, and 16% intermittently. Excessive straining to expel hard stools over time may also lead to dyssynergic defecation.

Pathophysiology

Earlier studies suggested that paradoxical anal contraction or involuntary anal spasm (anismus) during defecation may cause this problem. Consequently, myectomy of the anal sphincter was performed, but only 10% to 30% of patients improved. Likewise, paralyzing the anal sphincter muscle with botulinum toxin injections produced minimal improvement. Either spasm or inability to relax the external anal sphincter is unlikely to be the sole mechanism that leads to dyssynergic defecation.

A prospective study showed that most patients with dyssynergic defecation demonstrate the inability to coordinate the abdominal, rectoanal, and pelvic floor muscles to facilitate defecation. This failure of rectoanal coordination consists of impaired rectal contraction (61%); paradoxical anal contraction (78%); or inadequate anal relaxation. Incoordination or dyssynergia of the muscles that are involved in defecation is primarily responsible for this condition. In addition, 50% to 60% of patients also demonstrate an impaired rectal sensation.

Etiology and pathophysiology

Origin

How, when, and why an individual develops dyssynergic defecation is unclear. The authors’ prospective survey of 100 patients with dyssynergic suggested that the problem began during childhood in 31% of patients; after a particular event, such as pregnancy, trauma, or back injury in 29% of patients; and no identifiable precipitating cause in 40% of patients. Two thirds acquire this condition during adulthood. In this group, 17% reported a history of sexual abuse, 43% the passage of hard stools frequently, and 16% intermittently. Excessive straining to expel hard stools over time may also lead to dyssynergic defecation.

Pathophysiology

Earlier studies suggested that paradoxical anal contraction or involuntary anal spasm (anismus) during defecation may cause this problem. Consequently, myectomy of the anal sphincter was performed, but only 10% to 30% of patients improved. Likewise, paralyzing the anal sphincter muscle with botulinum toxin injections produced minimal improvement. Either spasm or inability to relax the external anal sphincter is unlikely to be the sole mechanism that leads to dyssynergic defecation.

A prospective study showed that most patients with dyssynergic defecation demonstrate the inability to coordinate the abdominal, rectoanal, and pelvic floor muscles to facilitate defecation. This failure of rectoanal coordination consists of impaired rectal contraction (61%); paradoxical anal contraction (78%); or inadequate anal relaxation. Incoordination or dyssynergia of the muscles that are involved in defecation is primarily responsible for this condition. In addition, 50% to 60% of patients also demonstrate an impaired rectal sensation.

Clinical features

Patients with dyssynergic defecation present with a variety of bowel symptoms. Often, patients do not volunteer or misrepresent their symptoms. For example, patients do not readily admit that they use digital maneuvers to disimpact stool or splint their vagina to facilitate defecation. By establishing a trustworthy relationship or through the help of symptom questionnaires or stool diaries, it may be possible to identify the precise nature of their bowel dysfunction. It is essential to determine this because only then can one approach this problem more rationally. In a prospective study, excessive straining was reported by 85%, a feeling of incomplete evacuation by 75%, the passage of hard stools by 65%, and a stool frequency of less than three bowel movements per week by 62% of patients. In addition, 66% of patients used digital maneuvers to facilitate defecation. In another study of 134 patients, two or fewer stools per week, laxative dependence, and constipation since childhood was associated with slow transit constipation, whereas backache, heartburn, anorectal surgery, and a lower prevalence of normal stool frequency was reported by patients with pelvic floor dysfunction. They concluded that symptoms are good predictors of transit time but poor predictors of pelvic floor dysfunction. A study of 190 constipated patients showed that stool frequency alone was of little value in constipation. In contrast, a sense of obstruction or digital evacuation was specific but not sensitive for disordered dysfunction. They also concluded that symptoms alone cannot differentiate between the pathophysiologic subgroups that lead to constipation.

Differential diagnosis includes many structural or functional abnormalities that may also lead to an evacuation disorder, such as rectocele, hypertensive anal sphincter, hemorrhoids, anal fissure, anorectal neoplasia, rectal prolapse, and proctitis. These conditions can be readily identified through appropriate testing. In contrast, functional evacuation disorders are less well recognized and poorly managed. These include dyssynergic defecation, excessive perineal descent, and mucosal intussusception. Also, paradoxical anal contraction has been described in patients after pouch reconstruction. Many patients with the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome also exhibit dyssynergic defecation.

Patients with defecation disorders have several psychologic abnormalities. This includes such problems as obsessive-compulsive disorder, where the patient believes that having a bowel movement everyday or sometimes several times per day are the norm. A deviation from this process compels the individual to use laxatives, enemas, suppositories, or any other means to achieve an unphysiologic pattern of bowel movement. Others have phobia for stool impaction. This particularly affects children, who then learn quickly to exploit minor disturbance in defecation for seeking attention. The problem may also be driven by psychosocial issues, such as interparental or parental-child conflicts or sibling rivalry. It has been shown that parental disattachment during childhood can lead to bowel dysfunction in adult life. Finally, patients with bulimia or anorexia nervosa and others with a history of physical or sexual abuse may also develop profound defecation problems.

Diagnostic procedures

General Issues

The first step in making a diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation is to exclude an underlying metabolic or pathologic disorder. Slow transit constipation may coexist with dyssynergic defecation, and hence an assessment of colonic motor function and transit is useful. An evaluation of the distal colonic mucosa through flexible sigmoidoscopy may provide evidence for chronic laxative use and may reveal melanosis coli or other mucosal lesions, such as solitary ulcer syndrome, inflammation, or malignancy.

Digital Rectal Examination

A careful perianal and digital rectal examination is not only important but often the most revealing part of clinical evaluation. Anorectal inspection can detect skin excoriation, skin tags, anal fissures, or hemorrhoids. Assessment of perineal sensation and anocutaneous reflex by gently stroking the perianal skin with a cotton bud or blunt needle in all four quadrants elicits reflex contraction of the external anal sphincter. If this is absent, a neuropathy should be suspected. Digital rectal examination may reveal a stricture, spasm, tenderness, mass, blood, or stool. If stool is present, its consistency should be noted and the patient should be asked if they were aware of its presence. A lack of awareness of stool in the rectum may suggest rectal hyposensitivity. It is useful to assess the resting and squeeze tone of the anal sphincter and puborectalis muscle by asking the subject to squeeze. More importantly, the subject should be asked to push and bear down as if to defecate. During this maneuver, the examiner should perceive relaxation of the external anal sphincter or the puborectalis muscle, together with perineal descent. A hand placed on the abdomen can gauge the abdominal push effort. An absence of these normal findings should raise the index of suspicion for an evacuation disorder, such as dyssynergic defecation. Digital rectal examination has a high sensitivity for identifying dyssynergia. Even though digital rectal examination is a useful clinical tool, there is a lack of knowledge on how to perform a comprehensive evaluation. A survey of 256 final year medical students revealed that 17% had never performed a digital rectal examination and 48% were unsure of giving an opinion based on their findings. A concerted effort is needed to improve the training of digital rectal examination.

Anorectal Manometry

This test provides a comprehensive assessment of pressure activity in the rectum and anal sphincter region together with an assessment of rectal sensation, rectoanal reflexes, and rectal compliance. Anorectal manometry is essential for a diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation. First, it excludes the possibility of Hirschsprung’s disease. Normally, when a balloon is distended in the rectum there is reflex relaxation of the internal anal sphincter that is mediated by the myenteric plexus. This reflex response is absent in patients with Hirschsprung’s disease. Second, it helps to detect abnormalities during attempted defecation. Normally, when a subject bears down or attempts to defecate, there is a rise in rectal pressure, which is synchronized with a relaxation of the external anal sphincter ( Fig. 2 ). This maneuver is under voluntary control and is primarily a learned response. The inability to perform this coordinated movement represents the chief pathophysiologic abnormality in patients with dyssynergic defecation. This may either be caused by impaired rectal contraction, paradoxical anal contraction, impaired anal relaxation, or a combination of these mechanisms. Based on these features at least four types of dyssynergia can be recognized (see Fig. 2 ).

Type 1: Here, the patient can generate an adequate pushing force (rise in intra-abdominal pressure) along with a paradoxical increase in anal sphincter pressure.

Type 2: Here, the patient is unable to generate an adequate pushing force (no increase in intrarectal pressure) but can exhibit a paradoxical anal contraction.

Type 3: Here, the patient can generate an adequate pushing force (increase in intrarectal pressure) but either has absent or incomplete (<20%) sphincter relaxation (ie, no decrease in anal sphincter pressure).

Type 4: The patient is unable to generate an adequate pushing force and demonstrates an absent or incomplete anal sphincter relaxation.

In addition to the motor abnormalities described previously, sensory dysfunction may also be present. Both the first sensation and the threshold for a desire to defecate may be higher in about 60% of patients with dyssynergic defecation. This may also be associated with increased rectal compliance. It must be noted that during attempted defecation some subjects may not produce a normal relaxation largely because of the laboratory conditions. Hence, this pattern alone should not be considered diagnostic of dyssynergic defecation (see diagnostic criteria later).

By observing the attempts to defecate, it is possible to identify the recording that most closely resembles a normal pattern of defecation. This recording can then be used to measure the intrarectal pressure, the anal residual pressure, and the percentage of anal relaxation. The residual anal pressure is defined as the difference between the baseline pressure and the lowest (residual) pressure within the anal canal when the subject is bearing down. The percent of anal relaxation is calculated using the formula, percent anal relaxation = anal relaxation pressure/anal resting pressure × 100. From these measurements it is possible to derive an index of the forces required to perform defecation (the defecation index). The defecation index may serve as a simple and useful quantitative measure of the rectoanal coordination during defecation.

Balloon Expulsion Test

In this test, either a silicone-filled stool-like device, such as the fecom, or a 4-cm-long balloon filled with 50 mL of warm water is placed in the rectum. A stop watch is started and the attendant leaves the room to provide privacy for the patient during balloon expulsion. The patient is then asked to expel the device and to stop the clock. Most normal subjects can expel a stool-like device within 1 minute, failing which dyssynergic defecation should be suspected. Although quite specific for dyssynergia, its sensitivity is approximately 50%.

Defecography

Defecography is commonly performed by placing approximately 150 mL of barium paste into the patient’s rectum. The patient is asked to sit on a special commode adjacent to a videofluoroscopic imaging system. The patient is instructed to squeeze or to evacuate the barium, and simultaneously the structural and functional changes of the anorectum are monitored by fluoroscopy and recorded on a videotape. This test provides useful information about anatomic and functional changes. In patients with dyssynergic defecation, the test may reveal poor activation of levator muscles, prolonged retention of contrast material or inability to expel the barium, or the absence of a stripping wave in the rectum.

Patients often, however, find this test embarrassing. Also, the type and consistency of barium paste varies considerably among different centers. Because of these inherent deficiencies, this test should be regarded as an adjunct to clinical and manometric assessment of anorectal function and should not be relied on as a sole test for assessing an evacuation disorder.

Diagnostic Criteria for Dyssynergic Defecation

Most published studies have used arbitrary or symptomatic diagnostic criteria. For example, paradoxical anal contraction has been considered to be a sine qua non for dyssynergic defecation. One study reported during attempted defecation, however, that five patients showed either no change in the anal resting pressure or an insignificant (<20%) decrease; all of these patients failed to expel a balloon and also had greater than 50% retention of barium material during defecography. Similarly, two other patients were able to expel the balloon but had paradoxical anal contraction. Others have found that paradoxical anal contraction or insufficient (<20%) decrease in anal electromyographic (EMG) activity, colonic transit, and defecographic abnormalities were not exclusively seen in patients with difficult defecation and none of the three tests showed significant differences in the prevalence of anismus between patients with or without slow transit constipation. Similarly, about two thirds of patients with constipation had objective evidence of delayed transit or pelvic floor dysfunction and no single test could reliably identify any of the pathophysiologic groups of constipation. Because a given patient may exhibit some but not all of the aforementioned dysfunctions, it is important to use more than one yardstick to diagnose this condition. In a prospective study, the presence of constipation symptoms together with dyssynergic pattern of defecation and at least one additional abnormal test (eg, prolonged balloon expulsion time, prolonged colonic transit, or excessive barium retention with defecography) had a high diagnostic yield of identifying dyssynergic defecation. To diagnose this condition, it has been proposed that a patient must satisfy both the symptomatic and the physiologic criteria set forth in Box 1 .

A. Patients must satisfy the diagnostic criteria for functional chronic constipation (Rome III) and

B. Patients must demonstrate dyssynergia during repeated attempts to defecate

Dyssynergic or obstructive pattern of defecation (types 1–4) is defined as paradoxical increase in anal sphincter pressure (anal contraction) or less than 20% relaxation of the resting anal sphincter pressure or inadequate propulsive forces observed with manometry, imaging, or EMG recordings and

C. One or more of the following criteria during repeated attempts to defecate

- 1.

Inability to expel an artificial stool (50 mL water-filled balloon) within 1 minute

- 2.

A prolonged colonic transit time (ie, greater than five markers [>20% marker retention]) on a plain abdominal radiograph taken 120 hours after ingestion of one sitzmark capsule containing 24 radiopaque markers

- 3.

Inability to evacuate or greater than or equal to 50% retention of barium during defecography

- 1.

Modified from Rao SSC, Mudipalli RS, Stessman M, et al. Investigation of the utility of colorectal function tests and Rome II criteria in dyssynergic defecation (anismus). Neurogastroenterol Motil 2004;16:589–96; with permission.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree