Prolene Hernia System

David C. Treen Jr.

Prerequisite for the performance of any surgical procedure, and as important as technique, is a thorough working knowledge and understanding of the anatomy involved. Robert Condon said, “The anatomy of the inguinal region is misunderstood by some surgeons of all levels of seniority.” Appreciation of the complexity of groin anatomy eludes most surgical residents, and argues that groin hernia repair by surgical residents should be in the hands of the more senior trainees under supervision of expert attendings. The understanding of the pathology of hernia formation in this region is still evolving, and humbles us with each new discovery. The pursuit of the ideal solution for groin hernia repair therefore necessarily incorporates as a foundational cornerstone knowledge of the anatomy and pathology affecting the pelvic floor. Prosthetic devices whose design processes begin with these foundations will lead the way toward the ultimate goal.

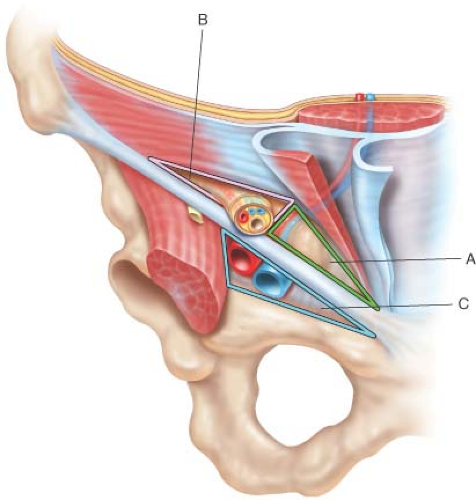

Fruchaud described the myopectineal orifice (MPO) (Fig. 4.1), as the area at risk for the development of groin hernia. This area of the MPO has been subdivided into three component triangles: medial, lateral, and femoral.

The integrity or vulnerability of the tissue within each triangle is dependent upon multiple variables, and can be enhanced or diminished by the introduction of mesh prosthetics in the repair of groin hernias. In the pre-mesh era of groin herniorraphy, prior to the introduction of the Lichtenstein onlay mesh technique, failures occurred predominantly in the medial triangle of the inguinal region, often adjacent to the pubic tubercle. Eventually, the reason generally accepted for these failures was the degree of tension created with the mobilization and suturing of tissues adjacent to the original defect. Following the adoption of tension-free methods employing various mesh materials and techniques, medial triangle recurrences became rare while recurrent hernias presenting through the lateral triangle became more common. This suggested that incomplete mesh coverage of all three triangles of the MPO at the original operation predisposed patients to recurrences in unprotected, more vulnerable locations.

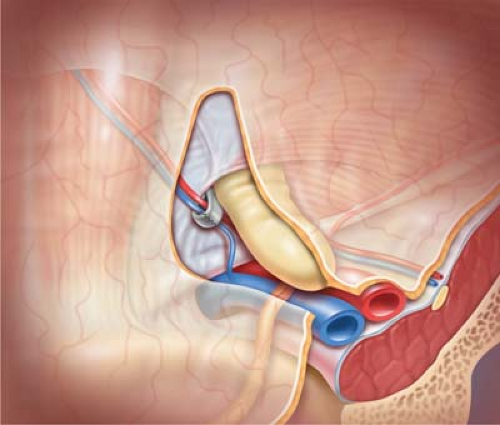

The Prolene Hernia System® (PHS) (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ) (Fig. 4.2) was developed by Dr. Arthur Gilbert and colleagues at the Hernia Institute of Florida, and was introduced in 1999. As described by Gilbert, the PHS is “a bilayer polypropylene (mesh) device” (PPM) intended for use in the repair of groin hernia including inguinal (direct, indirect, and recurrent) and femoral hernias. The impetus for the design of the PHS was to achieve positioning of a flat mesh inside the preperitoneal space (PPS) of the groin via a conventional anterior surgical approach. The goal of the technique

is to cover and protect the entirety of the myopectoneal orifice (MPO) within this PPS with the “underlay” mesh component, augmented by the addition of the second mesh layer in the floor of the inguinal canal. Use of the PHS has also been found to be efficacious in the repair of umbilical, epigastric, spigelian, and small incisional hernias, provided that protection of viscera is achievable with either preperitoneal placement of the underlay component, or by positioning the omentum immediately adjacent to the intraabdominal mesh. Recently developed similar devices, which employ tissue separating visceral protection components, have replaced the use of the PHS in many of these applications beyond the groin area. While our use of the PHS has been applicable to virtually any primary or recurrent groin hernia, including those with previous mesh, alternative techniques and materials should be considered in circumstances where the PPS is either inaccessible or obliterated by previous surgery or irradiation. It has been suggested that the use of mesh in the inguinal PPS should be avoided in patients at risk for future radical pelvic surgery such as prostatectomy;

however, reports have been published which refute this concern, and it is our belief that choice of technique and materials should not be limited by potential future pathology. Questions have also been raised about the potential adverse effect of mesh devices, particularly polypropylene, upon the integrity of the iliac vessels and the patency of the vas deferens. In our experience, and based upon other published reports, these concerns are unwarranted. Finally, hypersensitivity to polypropylene has been reported rarely, but remains an obvious contraindication to use of the PHS.

is to cover and protect the entirety of the myopectoneal orifice (MPO) within this PPS with the “underlay” mesh component, augmented by the addition of the second mesh layer in the floor of the inguinal canal. Use of the PHS has also been found to be efficacious in the repair of umbilical, epigastric, spigelian, and small incisional hernias, provided that protection of viscera is achievable with either preperitoneal placement of the underlay component, or by positioning the omentum immediately adjacent to the intraabdominal mesh. Recently developed similar devices, which employ tissue separating visceral protection components, have replaced the use of the PHS in many of these applications beyond the groin area. While our use of the PHS has been applicable to virtually any primary or recurrent groin hernia, including those with previous mesh, alternative techniques and materials should be considered in circumstances where the PPS is either inaccessible or obliterated by previous surgery or irradiation. It has been suggested that the use of mesh in the inguinal PPS should be avoided in patients at risk for future radical pelvic surgery such as prostatectomy;

however, reports have been published which refute this concern, and it is our belief that choice of technique and materials should not be limited by potential future pathology. Questions have also been raised about the potential adverse effect of mesh devices, particularly polypropylene, upon the integrity of the iliac vessels and the patency of the vas deferens. In our experience, and based upon other published reports, these concerns are unwarranted. Finally, hypersensitivity to polypropylene has been reported rarely, but remains an obvious contraindication to use of the PHS.

As in any surgical procedure, careful history and physical examination is essential. Assessment of the patient’s body habitus is important particularly in the case of severely obese individuals; as such anatomic obstacles may cause significant challenges to the performance of groin hernia repair. Accurate documentation of any previous abdominal, pelvic, vascular, or groin surgery can lead to the selection of an alternant approach to preperitoneal mesh placement for groin herniorraphy.

Skin infection or other conditions which could lead to poor healing or potential complications should be resolved when possible prior to implantation of any foreign body, particularly synthetic mesh. The use of enteral or parenteral perioperative antibiotics, and the practice of antibiotic irrigation during mesh herniorraphy have been debated for years. Most authors conclude that there is no statistically significant advantage to the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in the performance of routine inguinal hernia repair with or without synthetic mesh prosthesis. Nevertheless, many surgeons argue that antibiotic prophylaxis is both inexpensive and safe, and that such practice should not be considered inappropriate.

Anesthesia options for PHS repair include general, spinal, epidural, or local–regional anesthetic.

We have found that groin hernia repair with PHS using local anesthesia with regional infiltration is well tolerated; however, such is not the case in the repair of umbilical hernias with PHS or other preperitoneal or intraperitoneal devices, and our preference for umbilical hernia repair is general anesthesia.

Operative technique of initial dissection and exposure for the Prolene Hernia System repair is similar to standard methods of anterior approach to the inguinal region. Refer to the accompanying videos for all technique steps.

Skin preparation with clipping rather than shaving is preferred.

Gel prep cleansers reduce the incidence of caustic chemical skin irritation in the dependent skin folds near the thigh and perineum.

Surgical exposure of the inguinal region is accomplished through a 3 inch oblique incision minimizing dissection where possible. Appropriate retractors are placed, and stretching and pressure on the skin is avoided. In obese patients, Trendelenburg position can be advantageous.

The external oblique aponeurosis is opened in the direction of its fibers, and medial and lateral flaps of this layer are minimally mobilized and retracted.

Care is taken to preserve the ilioinguinal nerve, the iliohypogastric nerve, and the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve (GFN). In cases where a bifurcated nerve hinders necessary dissection, the minor branch is sacrificed sharply and ligated with fine, absorbable suture. It is widely agreed that an injured nerve is more problematic than a divided nerve; therefore, suspected injury warrants division and ligation.

The spermatic cord (SC) is encircled with a ¼ inch penrose drain, and gently retracted, allowing inspection of the inguinal floor. A direct hernia, if present, is separated from its attachments to the under surface of the cord structures.

The cremasteric muscle fibers are separated on the anteromedial aspect of the proximal SC, and careful search for an indirect hernia sac is completed. This is particularly important in cases of obvious direct hernia, as occult indirect hernias can be missed without diligent and careful dissection of the proximal SC as it exits the deep (internal) inguinal ring.

1. Indirect Inguinal Hernia Repair

The indirect hernia sac is carefully separated from the other structures within the interior of the SC, identifying and preserving the blood supply to the testis and the delicate investments and vessels attached to the vas deferens.

The hernia sac is separated from the vas deferens deep into the PPS most often with gentle blunt dissection using the tip of a finger or the back of a Debakey forcep. Rarely is sharp dissection necessary for this maneuver.

Attachments of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles to the neck of the hernia sac are released where these layers overlap the internal ring. This is particularly important to ensure that the hernia sac will be freed from the lateral triangle in order to permit separation of the peritoneum lateral to the internal ring.

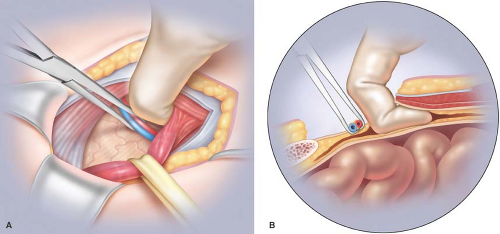

The deep epigastric vessels are identified in the medial rim of the internal ring, and are encircled with an Allis forcep, permitting medial retraction of the vessels while the hernia sac is retracted laterally (Fig. 4.3).

The tissue bridging between the deep epigastric vessels and the hernia sac is transversalis fascia (TF), and cutting through this TF affords entry into the PPS. The TF can be bi-laminate in this area, and in such cases may require deeper dissection to gain entry to the PPS. The fat within the PPS is readily identifiable, and palpation of Cooper’s ligament with the index finger through this internal ring confirms PPS access.

Blunt separation of the abundant fat in the PPS beneath the inguinal floor and along Cooper’s ligament with index finger and dry gauze clears the medial and femoral triangles of the MPO.

Continue the blunt finger dissection cephalad, beneath the deep epigastric vessels, and toward the lateral triangle. As the dissection proceeds laterally, the PPS will no longer contain fat, requiring attention to peel the peritoneum away from the overlying TF in order to create the lateral triangle space for optimal mesh deployment (Fig. 4.4).

The peritoneum is intimately applied over the iliac vessels and retroperitoneal segment of the vas deferens.

Figure 4.3 Parts (A) and (B): Dissection of the PPS (indirect hernia sac is omitted in illustration to avoid complexity).

Retracting the hernia sac cephalad, exposing the iliac vessels, and gently dissecting the peritoneum off the iliac vein completes the PPS dissection. There are several lymph nodes between the peritoneum and the iliac vein, which may or may not require dissection; however, surgeons who are new to this procedure are advised to exercise great care in separating these lymph nodes, and optimal mesh deployment overlying the iliac veins does not necessarily require this lymph node dissection.

Dissection of the PPS should be essentially bloodless, as no significant vessels traverse the PPS; however, previous pelvic surgery can alter the PPS significantly, and care is advised in these cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree