1

Preventive Gerontology in Men’s Health: Optimal Aging Concepts for Midlife and Beyond

Mortality, Morbidity, and Longevity in Men

Preventive gerontology is a concept applied to all stages of life whereby modifying risk factors that can promote aging can, in turn, improve longevity. Obvious examples include smoking cessation, diet, and exercise. This is to be differentiated from preventive geriatrics, which focuses on health maintenance and disease prevention when old age, with its associated frailty, has been reached.1,2

In the United States today, the average life span of men is about 7 years short of that of women. Arguably, women may have a long period of chronic illness, as life span is greater. The longevity of women is due to a variety of factors including genetics, endocrine, and perhaps lifestyle, along with arguably better preventive screening programs. Women, by and large, visit doctors more frequently, partly because of the need for help with reproductive issues. Screening for comorbid states such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes occurs more frequently in women. There are data supporting excess mortality and morbidity in men. In general, the four most important causes of death in men are cardiovascular disease, cancer, accidents, and suicide.

Coronary heart disease (CHD) was responsible for one of every five deaths in the United States in 1997. Although there is currently evidence that CHD may be as common in women as in men, symptoms of presentation may differ between men and women. In general, mortality rates of myocardial infarction in men are believed to be lower than those in woman.3 For example, 42% of women who have heart attacks die within 1 year compared with 24% of men. The reasons for this are not well understood. The explanation accepted by many is that women tend to get heart disease later in life than do men and are more likely to have other coexisting, chronic conditions. Studies also indicate that men and women react to drugs prescribed for heart disease and other conditions quite differently.

Because the United States is a heterogeneous society, cancer rates can differ based on ethnic backgrounds. The leading cancer in men, regardless of race, is prostate cancer, followed by lung/bronchus and colon/rectal. Prostate cancer rates are 1.5 times higher in black men than white men. Although it is important to realize the frequency of cancers, it is not quite the same with the way cancer affects morbidity and mortality. Prostate cancer and breast cancers are reported to be more common partly because of the availability of screening tools such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and mammograms. Autopsy results reveal that most men die with prostate cancer but not of prostate cancer. This contrasts with lung cancer, for instance, because lung cancer, when diagnosed, often is the terminal event. The leading cancer in women, regardless of race, is breast cancer, followed by lung/bronchus and colon/rectal in white women, and colon/rectal and lung/bronchus in black women. Breast cancer rates are ∼20% higher in white women than in black women. Melanomas of the skin and cancer of the testis are among the top 15 cancers for white men but not black men. Melanomas of the skin and cancer of the brain or other nervous systems are among the top 15 cancers for white women, but not black women. Multiple myeloma and cancer of the stomach are among the top 15 cancers for black women, but not white women. Multiple myeloma and cancer of the liver are among the top 15 cancers for black men, but not white men.4

As a measure of morbidity trends in men, a community-based British study revealed that the ailments that plagued men more than women include gout, duodenal ulcer, venereal disease, coronary heart disease, bladder cancer, and alcoholism.5 Knowledge of morbidity and mortality trends is useful, as it helps us plan for preventive strategies. Gout, duodenal ulcer, venereal disease, coronary heart disease, bladder cancer, and alcoholism are usually the result of lifestyle and environment issues and are modifiable.

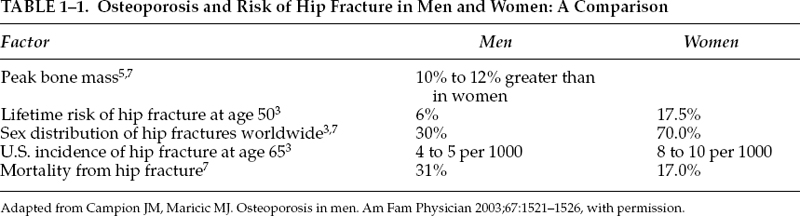

It is also interesting to study the life expectancy of men in different countries, as this may give us insight as to lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise. Life expectancy from birth, representing the average life span of a newborn, is an indicator of the overall health of a country. By and large, better life expectancy is the result of improvements in public health nutrition and prevention. The overall health of a country, however, is not a direct correlation of the wealth of the country (Fig. 1-1). For example, Saudi Arabia, which has a very high gross national product (GNP) per capita, has an average life expectancy of ∼68 years. This is actually less than that in El Salvador by 2 years and about the same as that in the Philippines. The countries with the highest average life expectancies are Andorra (84 years), San Marino (81 years), Japan (81 years), and Singapore (80 years). The average life expectancy in the United States in comparison is 77 years.6

In most countries, there is a longevity differential between men and women of ∼4 to 6 years. Andorra is a small country sandwiched between France and Spain that boasts of a Mediterranean climate. The foods are typically seafood and oils, including olive. Wine is a characteristic of the region. San Marino is also a small European country to the north of Italy, with similar Mediterranean attributes. It is also hilly, which implies that much walking has to be done. The Asian countries of Japan and Singapore are both modern and have good public health systems in place. The Japanese are known for their fondness for seafood and green tea, which may be responsible factors for their longevity.

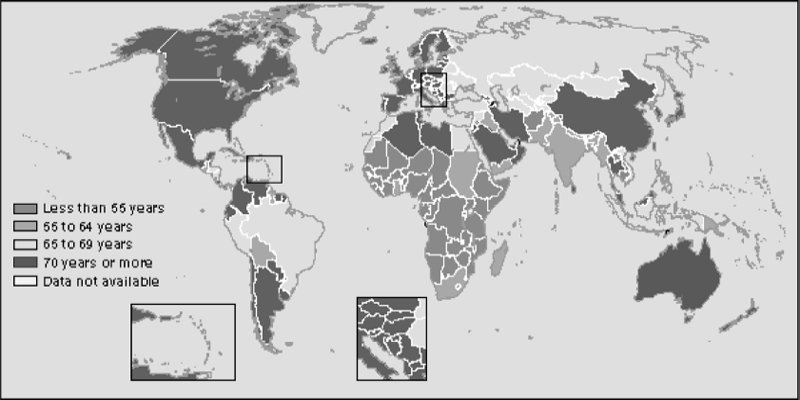

Recent research has suggested that there may be physiological markers for longevity. Three physiological measures associated with long-term caloric restriction in monkeys have been linked to longevity in men and include skin temperature, insulin, and dehdroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) levels.7 Roth et al7 compared more than 700 healthy men, ages 19 to 95, who participated in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA), with 60 rhesus monkeys, ages 5 to 25. The men were divided into two groups, based on whether they were in the upper or lower halves of the population for each of the three biomarkers: body temperature, blood insulin levels, and blood levels of DHEAS. The monkeys also were divided into two groups: one group was allowed to feed freely, typically consuming between 500 to 1000 calories daily; the other group was fed a diet composed of at least 30% fewer calories than consumed by the unrestricted monkeys. After analyzing the age-adjusted data, the investigators concluded that among men who participated in the BLSA, those who had lower body temperatures, lower blood insulin levels, or higher blood levels of DHEAS as they aged tended to live longer (Fig. 1-2). The calorie-restricted monkeys showed a similar trend and had half the death rate of monkeys allowed to feed freely. This study is obviously not conclusive, but we know that obesity is associated with higher levels of insulin, and obesity certainly is one of the modifiable risk factors for premature death.

FIGURE 1-1. This map shows the lifespans in different countries of the world.

FIGURE 1-2. Biomarkers of caloric restriction such as low temperature, low insulin, and high DHEAS levels may predict longevity. (Adapted from Roth GS, Lane MA, Ingram DK, et al. Biomarkers of caloric restriction may predict longevity in humans. Science 2002;297:811, with permission.)

The association of high insulin with diminished life span suggests that insulin resistance may play a part in the mortality of men. However, the association of low DHEAS with diminished life span does not necessarily imply that consuming dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) would improve longevity. That has yet to be determined, and there are no prospective controlled trials as yet.

Prevention and Implications for Longevity

Prevention has different components. In primary prevention, we educate our patients about risk factors and lifestyle changes that reduce risk. We also identify and alter risk factors to prevent the onset of disease. In contrast, secondary prevention refers to education and treatment after the onset of the disease, to limit its progress. It is intuitive to think that preventive strategies result in early detection of disease and as a result early intervention. Does it in the end lead to increase life expectancy, and better quality of life? There is ample scientific evidence that diet, exercise, alcohol moderation, and cessation of smoking are the major modifiable factors that lead to increased life expectancy. Interventions with hormonal replacement such as estrogen in women and testosterone in men have demonstrated improved quality of life, but the effects on longevity are not clear. The Women’s Health Initiative demonstrated that in women, replacement with an estrogen/progesterone preparation improved quality of life such as by decreasing hot flashes and improving osteoporosis.8 Unfortunately, this combination of hormones leads to an increase in thrombotic events. Testosterone replacement in physiological doses in men has definitely improved quality of life, but the long-term effects, though promising, remain unclear. This is not unlike many aspects of medicine, and as such testosterone replacement in men should be carefully monitored and individualized. Lifestyle changes should accompany any preventive medicine program. Preventive strategies altering cardiovascular risk factors such as treating high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia, and arguably inflammatory processes in the cardiovascular system and elsewhere can certainly decrease morbidity and mortality, and in turn result in enhanced longevity. Nutraceuticals is a large area of controversy in terms of whether it actually prevents disease. Chapter 20 discusses nutraceuticals and their impact on men.

Limitations of Current Guidelines for Preventive Medical Care

A very large interface with preventive care is cost and managed care. It is prudent to maintain health, and thereby decrease the long-term cost of health care. Indeed, health maintenance organizations (HMOs) are set up with that purpose in mind, as prevention decreases risk. Unfortunately, it would not be possible to be comprehensive with preventive programs under managed care programs because of cost. As such, only the basic preventive programs are recommended, such as a physical examination, rectal examinations, Pap smears, mammograms, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, etc. These procedures, although essential, must not be mistaken for a complete passage of a good bill of health. There are several recommendations from different bodies for preventive care. Interest groups such as the American Cancer Society have very tight guidelines for preventive care in the area of cancer. These contrast with those of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPTF), which relies much on evidence-based medicine in community-based practice. Though the USPTF recommendations are widely used, they may lack the following:

1. Gender-specific recommendations for men above 40 years of age. For instance, there is no mention of screening for hypogonadism, especially with the symptomatic. There are screening tools such as the Androgen Decline in Aging Males (ADAM) questionnaire. Erectile dysfunction may be a quality-of-life issue, but it also may be a harbinger for cardiovascular disease, and screening tools such as the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) exist. Despite the fact that prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men, USPTF does not recommend routine screening. This may be because of the limitations of the current methods for screening for prostate cancer.

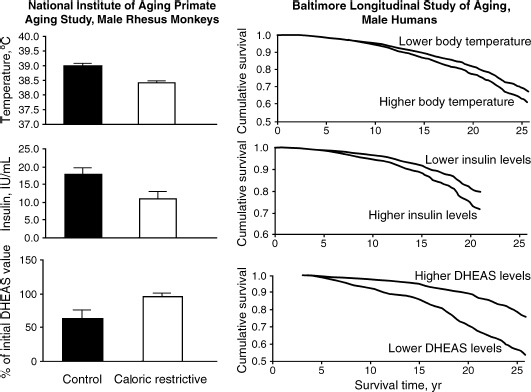

2. Gender-specific recommendations for prevention in men above 65 years of age. Osteoporosis also occurs in men, albeit later in life than in women. In fact, the mortality from hip fractures in men in later life is higher than that in women. Unfortunately, few men are screened for osteoporosis, or educated about smoking and alcohol as contributory factors (Table 1-1). Dementia is a function of age, and no routine screening is mentioned such as the Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE). Perhaps the reason is that the MMSE is not sensitive or specific enough as a tool to predict early dementia.9 There is also no screening for benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTSs), which are common ailments affecting men in this age group.

Emerging Concepts for Specific Areas of Prevention in Men

Prevention for our patients should take into consideration the guidelines, which at times should be individualized especially as new concepts are raised. But it takes time for a consensus among physicians to be built. Some of these emerging concepts are the following:

• Obesity is a universal health problem and is usually the result of an inactive lifestyle and paradoxically malnutrition. Obesity is often associated with the metabolic syndrome. Researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that as many as 47 million Americans may exhibit a cluster of medical conditions often termed the metabolic syndrome, which is characterized by insulin resistance and the presence of obesity, abdominal fat, high blood sugar and triglycerides, high blood cholesterol, and high blood pressure.10 Loss of weight is crucial to maintaining health and decreasing morbidity and mortality. One of the emerging concepts that has been debated is the use of the appropriate diet to lose weight and hence decrease the possibility of the metabolic syndrome. Proponents of a low-carbohydrate diet, including Atkins, Zone, Ornish, Wadden, and others have challenged the traditional Food and Drug Administration (FDA) food pyramid. To validate the Atkins diet, researchers recently completed a 1-year, multicenter, controlled trial involving 63 obese men and women who were randomly assigned to either a low-carbohydrate, high-protein, high-fat diet or a low-calorie, high-carbohydrate, low-fat (conventional) diet. Professional contact was minimal to replicate the approach used by most dieters. The low-carbohydrate diet produced a 4% greater weight loss than did the conventional diet for the first 6 months, but the differences were not significant at 1 year. The low-carbohydrate diet was associated with a greater improvement in some risk factors for coronary heart disease. Unfortunately, adherence was poor and attrition was high in both groups.11 Men seen in practice often ask which diet is best for them to lose weight, but exercise is important to keep the weight off in the long term. There is also ongoing research as to whether androgen replacement can decrease fat mass in men, and preliminary data suggest that it does.12 Chapter 11 discusses the impact of androgens on obesity in men.

• There have been many inroads in cardiovascular health prevention in recent years. High low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglycerides, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL), hypertension, and diabetes are no longer seen to be the only risk factors for coronary heart disease in men. LDL cholesterol is a serum lipoprotein that contains apolipoprotein B (ApoB), cholesterol, and triglycerides. LDL is the most atherogenic of the lipoproteins. Recent evidence suggests that the oxidized form of LDL may play a key role in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis, and like lipoprotein(a), oxidized LDL forms foam cells, which are associated with the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. Smoking and family history are other obvious risk factors. The following factors are other emerging concepts that can contribute to coronary heart disease:

∘ Elevated homocysteine: Homocysteine is a sulfur-containing amino acid, and when it becomes elevated, it can damage coronary arteries, cell structures, blood lipids, and artery walls, eventually leading to the development of atherosclerosis and other forms of heart disease. Vitamins B6, B12, and folate, involved in homocysteine metabolism, act to regulate and reduce homocysteine. The assessment of homocysteine status and B vitamins, particularly B6, B12, and folate, is useful because heart disease is the leading cause of fatality in the United States. In addition, current medical research reports that an elevated homocysteine status and/or deficiency of B6, B12, or folate increases the risk for heart disease. Approximately two thirds of cases with elevations in homocysteine are related to deficiencies of one or more of these B vitamins, and can be reversed potentially by supplementation of these micronutrients.

∘ Elevated lipoprotein(a) [LP(a)] is a complex of ApoA and LDL, and an elevated status is associated with an increased risk for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. The pathogenic role of Lp(a) is similar to that of LDL in the development of atherosclerosis; it is localized in the blood vessel walls, and then oxidized. When oxidized, it forms the foam cells associated with atherosclerotic plaques. Diet and exercise can potentially decrease levels of Lp(a).

∘ Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) is a nonspecific indicator of systemic inflammation and infection. One of the emerging concepts of heart disease is that it is inflammatory in nature, and results in endothelial dysfunction. CRP levels rise rapidly in response to tissue injury and inflammation. Exercise, aspirin, and a healthy diet can decrease CRP levels.

∘ Elevated fibrinogen status: Fibrinogen is an important coagulation protein that is involved in the mesh-like network of the common blood clot. Studies have shown that elevated fibrinogen status is associated with early coronary heart disease.

∘ Low apolipoprotein A-I and apolipoprotein B status: Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoAI) is the major protein constituent of HDL. This molecule is responsible for the activation of two enzymes that are necessary for the formation of HDL, and this process may be a key factor in the relationship between HDL levels and the incidence of atherosclerosis. On the other hand, apolipoprotein B (ApoB) is the primary protein found in LDL. Studies suggest that ApoB plays a major role in targeting the selective uptake of LDL by the liver, and it has been identified as one component of the syndrome known as atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype, which is a common disorder in persons at risk for atherosclerosis.

• Osteoporosis does not occur only in women. For instance, ∼30% of hip fractures occur in men, and one in eight men older than 50 years will have an osteoporotic fracture.13 As such, prevention of osteoporosis in men is also becoming an emerging health concept. Men’s bone integrity differs from that of women as they generally have greater peak bone mass. In addition, men usually present with hip, vertebral body, or distal wrist fractures 10 years later than women. Hip fractures in men, however, result in a much higher mortality rate at 1 year after fracture as compared with women (31% versus a rate of 17% in women). The major risk factors for osteoporosis in men are not only age related but also are associated with steroid use for longer than 6 months (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Hypogonadism remains a risk factor in men that is potentially reversible, and as such there has been recent interest in the area of testosterone replacement.14 The FDA has recently approved bisphosphonates and teriparatide (recombinant parathyroid hormone) for use in men, which should be considered along with supplemental calcium and vitamin D. If physicians are aware of modifiable risk factors for male osteoporosis such as alcoholism and smoking, the prevention of osteoporosis takes on another dimension. Preventing osteoporosis in the long term leads to the decrease in morbidity and mortality events that occur with falls and fractures. Chapter 9 discusses osteoporosis in men.

• Mental health in men is an often-neglected aspect of preventive medicine, despite the staggering fact that elderly men are more likely to commit suicide than elderly women. Epidemiological studies based on subjective reporting by patients suggest that depression may be less common in men than in women. However, men are less likely to report depression, and may manifest other problems such as anger, alcoholism, slacking work performance, and domestic violence. Prevention includes early detection and intervention with supportive therapy, psychotherapy, and medications. Gender differences and gender-specific treatments are discussed in a later chapter. Dementia, too, is perceived to be less common in men than in women. The difference can be explained by the longer life span of women because dementia is a function of age. Hormones such as estrogens and testosterone may influence cognitive function (see Chapter 7). Preventive strategies for dementia such as aspirin, gingko biloba, “brain exercises,” vitamin E, antiinflammatory drugs, etc., are exciting areas, and their efficacies are being examined in clinical trials at present.

• The most common cancers in men are skin, prostate, lung, and colorectal. These four cancers alone are expected to kill more than 150,000 men in the United States each year. Fortunately, with lifestyle changes and proper screening, physicians can help prevent these cancers or successfully treat them when detected in their early stages. Another common cancer that is found only in men is testicular cancer. The incidence of testicular cancer is ∼7000 per year. Fortunately, testicular cancer is treatable when detected early. The world-champion cyclist Lance Armstrong has been one of the advocates in this area of preventive health, having survived this cancer himself. As the disease tends to develop at younger ages than other cancers, young men should be taught to regularly practice self-exams, not unlike women performing breast self-examinations. As in heart disease, research has shown that diet and exercise can be pivotal in the prevention of cancers in men. Genetics is also an important factor.

• Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) has had a profound impact on the early diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of prostate cancer, the most common malignancy in men. However, it is not only a marker for prostate cancer but is also often expressed in benign conditions such as benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatitis, and other inflammatory disorders. We have been trying to make the PSA test even more useful for several years. Most of these attempts, such as PSA density, PSA velocity, and age-dependent PSA ranges, were impossible to verify and thus not very useful. One of the newer tests developed, and an emerging concept in preventive health in prostate cancer, is the free PSA test. Free PSA is both reproducible and useful. Free PSA is the percentage of the total PSA that circulates in the blood without a carrier protein. Most patients with prostate cancer have a free PSA less than 15%. The ratio of free to total PSA improves specificity while maintaining a high sensitivity for prostate cancer detection for men with a total PSA of 2.5 to 10ng/mL who also have a normal digital rectal examination. Complex PSA seems to be a reliable tool and equivalent alternative to total PSA to improve specificity at high sensitivity levels in men with suspected prostate cancer, mainly for PSA levels below 4ng/mL. Several newly discovered isoforms of free PSA (bPSA, [-2]pPSA, and inactive intact PSA) may also impact the early detection of prostate cancer, with encouraging preliminary results that warrant further clinical investigation.15

∘ Human glandular kallikrein 2 (hK2) also has the potential to be a valuable tool in combination with both total and free PSA for the early diagnosis of prostate cancer. Patients with high hK2 measurements have a five- to eightfold increase in risk for prostate cancer, adjusting for PSA level and other established risk factors. As such, hK2 measurements may be a useful adjunct to PSA in improving patient selection for prostate biopsy. However, the optimal clinical use of human glandular kallikrein 2 still remains to be clarified.16

∘ The education of both men and women is one of the first important steps in prevention of sexually transmitted disease (STD). Other preventive strategies include administering the hepatitis B vaccine series to unimmunized men who present for STD evaluation and administering hepatitis A vaccine to illegal drug users and men who have sex with men. Nonoxynol 9 is a chemical that has been introduced recently for STD prevention, but the CDC recommends against prescribing it at present because the results from clinical trials have been conflicting. New treatment strategies include avoiding the overuse of quinolone therapy in patients who contract gonorrhea because of resistance. Testing for herpes simplex virus serotype is advised in patients with genital infection because recurrent infection is less likely with the type 1 serotype than with the type 2 serotype. HIV screening remains important in men at risk, such as homosexuals, intravenous drug abusers, and those who had transfusions in the past. Informed consent is necessary for testing.

• Many men are now appearing for health care because they are requesting help with erectile dysfunction (ED). This gives an excellent opportunity for screening and preventive medicine. A British study suggests that ED shares many of the same risk factors as coronary artery disease, so the level of occult cardiovascular risk in men with ED was assessed. A total of 174 men presenting with ED underwent cardiac risk stratification according to the Princeton Consensus Guidelines. Thirty percent were stratified as intermediate/high cardiovascular risk and had ED treatment deferred until further cardiological assessment; 37% had abnormal lipid profiles; 24% had elevated hemoglobin HbA1C/glucose levels; 17% had uncontrolled hypertension; and 6% were suspected of having significant angina.17 The role of stress testing for detection of occult cardiovascular disease in men is currently being explored in clinical trials, in light of the finding that many of these patients presenting with ED have underlying untreated occult heart disease. ED is a window to many illnesses, including not only coronary heart disease but also depression.18 Chapter 15 discusses the interlinked syndrome of depression, ED, and CHD, known as the DEC syndrome.

• Total-body computed tomography (CT) screening has been becoming very popular with patients partly because of direct marketing by radiological practices. However, many organizations, including the FDA and the American College of Radiology (ACR), do not endorse total-body CT screening because of the lack of evidence that it is useful in prevention. This is especially so in patients with no symptoms or a family history suggesting disease. In addition, there is no evidence that total-body CT screening is cost-efficient or -effective in prolonging life. In addition, the ACR is concerned that this procedure will lead to the discovery of numerous findings that will not ultimately affect patients’ health but will result in unnecessary follow-up examinations and treatments and significant wasted expense. However, the ACR stated recently that CT screening targeted at specific diseases might be useful. Early data suggest that these targeted examinations may be clinically valid. Large, prospective, multicenter trials are currently under way or in the planning phase to evaluate whether these screening exams reduce the rate of mortality. As such, these exams may again represent yet another area of emerging concepts in prevention in men.

• Lung scanning for cancer in current and former smokers remains controversial but promising, if cost is not a factor. This has potential significance as chest x-rays lack sensitivity and specificity, and lesions are only detected late. Moreover, lung cancer is one of the most common cancers in men and is associated with the highest mortality when diagnosed. In a recent study by Mahadeivia et al,19 using a computer-simulated model, annual helical CT screening was compared with no screening for hypothetical cohorts of 100,000 current, quitting, and former heavy smokers, aged 60 years, 55% of whom were men. The authors simulated efficacy by changing the clinical stage distribution of lung cancers so that the screened group would have fewer advanced-stage cancers and more localized-stage cancers than the nonscreened group (i.e., a stage shift). The model incorporated known biases in screening programs such as lead time, length, and overdiagnosis bias. Over a 20-year period, assuming a 50% stage shift, the current heavy smoker cohort had 553 fewer lung cancer deaths (13% lung cancer–specific mortality reduction) and 1186 false-positive invasive procedures per 100,000 persons. The incremental cost-effectiveness for current smokers was $116,300 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained. For quitting and former smokers, the incremental cost-effectiveness was $558,600 and $2,322,700 per QALY gained, respectively. The authors concluded that even if efficacy is eventually proven, screening must overcome multiple additional barriers to be highly cost-effective. They also said that given the current uncertainty of benefits, the harms from invasive testing, and the high costs associated with screening, direct-to-consumer marketing of helical CT is not advisable at this point, and further research is needed.19

• Coronary artery calcium scoring as a predictor of cardiac events is also becoming more common and is fairly well studied. There are reports that very high calcium scores, in particular those >1000, indicate a significantly increased cardiovascular risk. The advent of cardiac spiral CT has made coronary calcium scanning more widely available. In a recent study in Germany, Pohle et al20 compared the presence and extent of coronary calcifications in young patients with first, unheralded acute myocardial infarction with matched controls without a history of coronary artery disease. Calcifications were present in 95.1% of patients with acute myocardial infarction but in only 59.1% of controls (p =.008). Using calcium scoring at this point remains promising but is seen to be an additional aid to screening for heart disease and does not replace existing standards for screening.

• CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) for colon cancer is another area of controversy. Preliminary small studies have suggested that in good hands, the accuracy may supersede that of barium enema and approaches that of colonoscopy. It offers convenience to the patient and is less uncomfortable as a procedure. The accuracy of the technique is continually being challenged. At this point, it is probably the preferred screening test for patients with an incomplete colonoscopy, or for those patients who cannot undergo colonoscopy because of advanced age, for instance. Its precise role in screening average-risk patients for colon cancer remains to be defined by ongoing research and clinical trials.

• Hormonal decline with aging is inevitable, and there are generally two schools of thought about whether to intervene with hormones. There is a general consensus that thyroxine should be substituted when the patient is hypothyroid. However, if DHEA levels were low such as in the so-called “adrenopause,” or if growth hormone were low in the “somatopause,” then the role of substitution is less clear, especially with the lack of symptoms. There are no large clinical trials that are sufficiently long term to suggest the benefits of hormonal replacement as a means of prevention. However, clinical experience does suggest that these compounds can be extremely potent, and can improve quality of life substantially. The main concern about the long-term use of these hormones is the possibility of carcinogenesis. There is one school of thought that suggests that the low hormonal milieu protects one from cancer, and that replacement to youthful physiological levels may do harm. On the other hand, there is another school of thought that believes that the low hormonal state in itself is associated with cancer. One argument for the use of testosterone has been that it has been observed that prostate cancer tends to occur in older men, and that older men tend to be more likely to be hypogonadal as compared with younger men. Aging is a complex event that involves genetic expression, environmental interactions, and lifestyle habits. Aging and death are inevitable. Hormones, when replaced to youthful physiological levels, can improve substantially the quality of life for the patient. At present, there is no evidence to suggest that hormones have an anti-aging effect, but rather that they can restore function and improve biological and physiological markers. Measurements of biological age against chronological age remains a novel approach, and if used appropriately, may motivate patients to improve their health through lifestyle changes. The area of hormonal replacement for men is evolving; at present, replacement should be reserved for those patients who are symptomatic, and patients should be carefully monitored. The role of hormonal replacement for men for prevention remains promising, and only time will tell of its efficacy.

The previous issues are discussed throughout this book, and are illustrated through the use of case histories.

Conclusion: Optimal Aging

Rather than pursue the reversal of age or anti-aging, perhaps the real role of prevention in aging is to achieve the concept of optimal aging. In the hospital, we often attend to patients who are in their 40s or 50s but who look as if they are in their 60s or 70s because of their chronic illnesses. In fact, Medicare recognizes this and allows the enrollment of patients before age 65 if they have multiple chronic illnesses and are disabled at the same time. Hence we see patients that are chronologically young, but biologically old. Optimal aging intends that we practice the best form of preventive medicine so that patients will remain healthy as they age gracefully. As such, optimal aging as applied to a 40- or 50-year-old man may mean drastic attention to weight and controlling blood pressure, risk factors for heart disease, and diabetes. It also means attention to lifestyle factors such as smoking and excessive drinking. Patients who consult for problems of hypogonadism or erectile dysfunction should have a thorough evaluation of their associated risk factors. Hormones can be prescribed if symptomatic and biological measurements support a low level. On the other hand, optimal aging as applied to a 75-year-old man may mean maintaining his functionality, such as the prevention of falls. This could be achieved through muscle strengthening exercises and balance training, and in some instances hormonal replacement. Bone integrity can be improved and maintained with drugs such as Fosamax. A 75-year-old man may also face memory loss, and prevention may entail the prescription of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as Aricept, Exelon, or Reminyl. These groups of drugs do not improve memory but they should be seen as preventing further decline. Maintaining use of cognitive functions is important to prevent loss of function. Family and social support can also be seen as a form of preventive medicine.

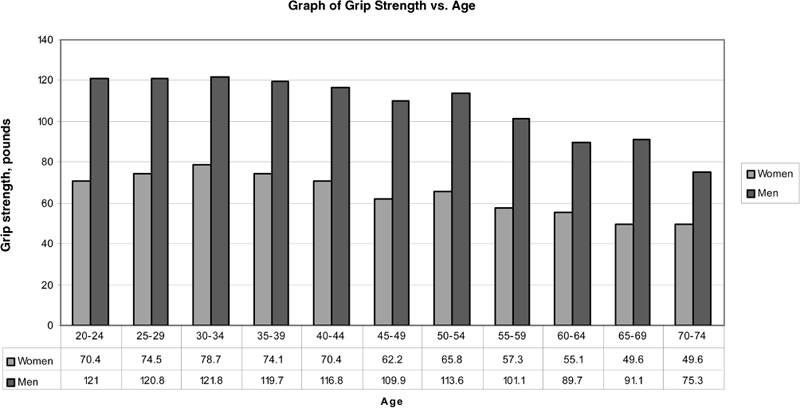

There is an emerging concept that chronological age is not quite the same as biological age, and one of the principles of preventive gerontology is to decrease biological age, as chronological age will not change. There are many so-called biomarkers of aging, which are really tests of physiological functionality as compared with the same age cohorts. Normative age-matched values are used for comparison. For example, grip strength has normative values and can be used for age comparison (Fig. 1-3).

Another commonly used test includes taking measurements of subjects and then comparing them with normative values for neuropsychological batteries (e.g., Brief Visual Spatial Memory Test), cognitive reflexes, and pulmonary function. These tests could be used as a motivation for patients to achieve a healthier lifestyle. Normative values can vary based on factors such as body size, activity, genetics, and ethnicity. As such, these physiological measures are useful only for intraindividual comparison over time, rather than interindividual comparisons.

Genetics also plays a major role in longevity; as such, prevention even to the highest level may have limitations. There is a discussion on genetics and why we age in Chapter 2. However, aging is also a function of how genes express themselves, and some people are just more fortunate than others. Longevity should be accompanied by improvement of quality of life. It should be appreciated that human life expectancy has improved dramatically through achievements in public health, therapy, nutrition, and general living standards. But as humans reach their possible age limits, it is always important to remember the old axiom, “Death and taxes are inevitable.”

FIGURE 1-3. Normative values of dominant hand grip strength versus age. (Adapted from Mathiowetz V, et al. Grip and pinch strength: normative data for adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1985;66:69–74, with permission.)

REFERENCES

1. Hazzard WR. Preventive gerontology: optimizing health and longevity for men and women across the lifespan. J Gend Specif Med 2000;3:28–34

2. Hazzard WR. The gender differential in longevity. In: Hazzard, et al. Principles of Geriatric Medicine. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999:69–80

3. Ettinger SM. Myocardial infarction and unstable angina: gender differences in therapy and outcomes. Curr Womens Health Rep 2003;3:140–148

4. CDC. United States Cancer Statistics, 1999. Atlanta: CDC; 1999

5. McCormick A, Charlton J, Fleming D. Assessing health needs in primary care: morbidity study from general practice provides another source of information. BMJ 1995;310:1534

6. 2000 United States Census Bureau International Data Base

7. Roth GS, Lane MA, Ingram DK, et al. Biomarkers of caloric restriction may predict longevity in humans. Science 2002;297:811–815

8. Wassertheil-Smoller S, Hendrix SL, Limacher M, et al. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on stroke in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative: a randomized trial. JAMA 2003;289:2673–2684

9. Anthony JC, LeResche L, Niaz U, et al. Limits of the “Mini-Mental State” as a screening test for dementia and delirium among hospital patients. Psychol Med 1982;12:397–408

10. Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA 2002;288:2709–2716

11. Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, et al. A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet for obesity. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2082–2090

12. Tan RS, Pu SJ. Impact of obesity on hypogonadism in the andropause. Int J Androl 2002;25:195–201

13. Campion JM, Maricic MJ. Osteoporosis in men. Am Fam Physician 2003;67:1521–1526

14. Tan RS, Culberson JW. An integrative review on current evidence of testosterone replacement therapy for the andropause. Maturitas 2003;45:15–27

15. Haese A, Partin AW. New serum tests for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Drugs Today (Barc) 2001;37:607–616

16. Nam RK, Diamandis EP, Toi A, et al. Serum human glandular kallikrein-2 protease levels predict the presence of prostate cancer among men with elevated prostate-specific antigen. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:1036–1042

17. Solomon H, Man J, Wierzbicki AS, et al. Erectile dysfunction: cardiovascular risk and the role of the cardiologist. Int J Clin Pract 2003;57:96–99

18. Tan RS, Pu SJ. The interlinked depression, erectile dysfunction, and coronary heart disease syndrome in older men: a triad often underdiagnosed. J Gend Specif Med 2003;6: 31–36

19. Mahadevia PJ, Fleisher LA, Frick KD, et al. Lung cancer screening with helical computed tomography in older adult smokers: a decision and cost-effectiveness analysis. JAMA 2003;289:313–322

20. Pohle K, Ropers D, Maffert R, et al. Coronary calcifications in young patients with first, unheralded myocardial infarction: a risk factor matched analysis by electron beam tomography. Heart 2003;89:625–628

< div class='tao-gold-member'>