Chapter 9 Preparation for ERCP

Should This Patient Undergo ERCP?

The advent and refinement of alternative technologies, including magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), that provide similar (or better) diagnostic information about the pancreas and biliary tree has essentially restricted the role of ERCP to a therapeutic procedure.1–3 For this reason, critically questioning the strength of the indication for ERCP is the first step in planning. The answer to the question “Should this patient undergo ERCP?” may range from “yes” to “no” to “not yet.” In some cases ERCP is clearly not indicated (e.g., simply as a diagnostic test for abdominal pain), while other cases may be more nuanced, such as a reasonably healthy patient with new painless jaundice and a small mass in the head of the pancreas that appears resectable. Additionally, the efficacy and safety of ERCP may be enhanced in some patients by delaying the ERCP—for example, to allow for an MRCP that can provide a road map in a patient with a suspected hilar malignancy4 or to allow the correction of a coagulopathy before an elective ERCP.

When, Where, and by Whom?

Once the decision has been made that an ERCP is indicated, the next decision points relate to urgency, locale, and the potential need for other physician assistance. The vast majority of ERCPs do not need to be conducted on an urgent basis. Patients with severe acute cholangitis not responding to antibiotics and fluid resuscitation represent the lone group in whom a truly urgent procedure is indicated.5–7 However, there may be other instances in which a reasonably expedited ERCP is desirable, including in patients with mild to moderately severe acute cholangitis who are responding to conservative treatment.8

Critically ill patients, such as those receiving mechanical ventilation and vasopressors, may not be appropriate for transfer to the endoscopy lab or radiology department for ERCP. In these instances, other options must often be explored, including performing the ERCP in a dedicated intensive care unit (ICU) procedure room or nearby operating room, in the ICU at the bedside with a portable C-arm fluoroscopy unit,9 or in the patient’s room without fluoroscopy (i.e., using bile aspiration to confirm location).10 Many fluoroscopy tables have a weight limit of 350 lb (159 kg); some morbidly obese patients requiring ERCP may exceed these limits and must be cared for in an operating room with an appropriately rated table and portable fluoroscopy.11

Additional scheduling coordination is necessary for ERCPs requiring a second physician. Most commonly this occurs with “rendezvous” procedures in which an interventional radiologist or echoendoscopist performs either a percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram or an internal puncture and passes a wire antegradely across the major papilla into the duodenum to facilitate endoscopic retrograde cannulation (see Chapter 31).12,13 Another instance of collaborative ERCP is laparoscopic-assisted ERCP for patients with prior Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, in which a laparoscopic gastrostomy is created into the excluded stomach and, during the same procedure, a duodenoscope is passed via the gastrostomy to perform ERCP.14,15

Evaluation of the Patient Prior to ERCP

History and Physical Examination

A thorough history and physical examination should be completed on all patients prior to ERCP. Comorbid medical conditions may affect ERCP decision making in a number of ways, including need for preanesthesia testing, method of sedation chosen, management of antithrombotic agents, and need for postprocedure inpatient observation, among others. However, in some systems of care, the endoscopist performing the ERCP may not meet the patient until shortly before the scheduled procedure. This may occur in the hospital setting when a GI trainee or surgical service has evaluated an inpatient, or in the outpatient setting when a patient is referred by another gastroenterologist for ERCP. In some instances there are nuances to the case that may not be apparent on initial review, but that affect the appropriateness of the procedure. One example would be a minimally symptomatic elderly patient with advanced pancreatic malignancy and very poor functional status, in whom hospice care may be more appropriate than biliary decompression. In patients who have had prior surgery involving the foregut or biliary tree, it is critical to have the best possible understanding of their anatomy prior to embarking on ERCP. Many patients may be unable to provide a history more detailed than “stomach surgery,” and even referring physicians may not appreciate the implications of various reconstructions as they relate to ERCP. As such, when postsurgical anatomy is uncertain, obtaining the operative notes for review or speaking with the surgeon for clarification is recommended (see Chapter 29). The nature of the surgically altered anatomy and the skill set of the endoscopist will influence whether to perform or refer the procedure, and certainly will influence endoscope and device selection if the ERCP is undertaken.16,17

Laboratory Testing

The practice of routinely ordering laboratory tests prior to ERCP, irrespective of the specific clinical setting, is not recommended due to high cost and low yield.18 However, there are instances in which selected preprocedure testing may be appropriate, tailored to the patient’s specific clinical scenario and comorbidities. In patients with a known bleeding disorder, liver disease, malnutrition, or prolonged biliary obstruction, and in those receiving warfarin treatment, testing of the prothrombin time (PT) and international normalized ratio (INR) may be considered.19,20 Routine measurement of the hemoglobin/hematocrit and platelet count is not necessary, but may be appropriate in the setting of suspected anemia, perceived high risk for bleeding, myeloproliferative disorders, splenomegaly, and medications known to cause thrombocytopenia.19,21,22 All women of childbearing age should be asked about the possibility of pregnancy, and pregnancy testing may be considered in this patient subset.23,24 A chemistry panel may be considered for patients with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease, and in the setting of medications that may cause abnormalities of glucose, potassium, or renal function.19,25 Finally, electrocardiography (ECG) and chest radiography may be considered in older patients with cardiopulmonary comorbidities; although not routinely necessary prior to ERCP,19,22 these are often required by anesthesia providers as part of routine anesthesia clinical care. In a practice guideline from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) the issue of laboratory testing before endoscopic procedures is discussed in detail.18

Review of Imaging Studies

While each patient has undergone at least one pancreaticobiliary imaging study, it is useful to personally review these prior to ERCP. Anecdotally, it is not uncommon to detect potentially relevant findings not described in the radiologist’s report, such as pancreas divisum or a subtly dilated pancreatic duct on abdominal computed tomography (CT; see Chapter 34). Reported findings may not be described in adequate detail. For example, a CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) report may describe a malignant-appearing hilar stricture with intrahepatic biliary dilation but omit key findings such as apparent Bismuth classification or lobar atrophy that is relevant to the patient’s management. Review of prior cholangiograms, including those obtained percutaneously, endoscopically, and intraoperatively, is absolutely necessary.

Preparing the Patient—Day(s) Prior to ERCP

Management of Antithrombotic Agents

The central issue in the periendoscopic management of antithrombotic agents (e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel, warfarin) is balancing the risk for bleeding caused by the endoscopy against the risk for thromboembolic events caused by withholding these agents. An ASGE practice guideline titled “Management of Antithrombotic Agents for Endoscopic Procedures” provides a thorough review of the relevant data available on this topic.26

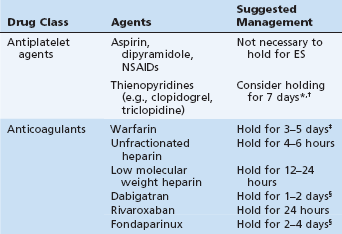

The risk for clinically relevant bleeding at ERCP is almost entirely derived from the performance of endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES).27–30 ERCP without ES poses very little risk for bleeding, even in the setting of antithrombotic agents, and it is unnecessary to withhold these agents prior to ERCP if ES is not planned or has previously been performed. However, the need for access (precut sphincterotomy) is always a possibility in the presence of a native papilla. The following paragraphs will discuss the management of antithrombotic agents when ERCP with ES is contemplated. A summary of commonly encountered antithrombotic agents and the suggested management of these agents prior to ERCP with ES is presented in Table 9.1.

Table 9.1 Management of Antithrombotic Medications Prior to Elective ERCP with Sphincterotomy

NSAID, Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.

*Avoid stopping thienopyridine until the minimum recommended treatment interval has been completed in patients with coronary stents.

†Sphincterotomy may be considered in patients on thienopyridine monotherapy; alternatively, stop the thienopyridine 1 week in advance and start aspirin.

‡Employ bridging therapy for high-risk conditions.

Antiplatelet Agents

Two retrospective case control series and a large prospective multicenter trial of ES adverse events suggest that aspirin is not a risk factor for post-ES bleeding.31–33 Conversely, results from a cohort study of 804 patients who underwent ES—including 124 patients actively taking aspirin, 116 patients in whom aspirin was discontinued 1 week prior to ES, and 564 patients who had never used aspirin34—showed the rate of post-ES bleeding to be higher in the two aspirin groups (9.6%) than in the never-users (3.9%, p = 0.01). There was no difference between those who had stopped taking aspirin for 1 week (9.5%) versus those actively taking aspirin (9.7%, p = not significant). However, the rate of post-ES bleeding across all groups in this series was unusually high, thus these findings must be interpreted with some caution. Overall, the available data suggest that aspirin does not pose a significant risk for post-ES bleeding and that withholding aspirin does not reduce the likelihood of post-ES bleeding.

There are no data specifically addressing the bleeding risk posed by ES in the setting of thienopyridine usage (e.g., clopidogrel, ticlopidine). Two large case control series examined the risk for bleeding after colonoscopic polypectomy on clopidogrel, which may be of analogous risk to post-ES bleeding.35,36 One of these studies noted an increased risk for delayed postpolypectomy bleeding with clopidogrel users (3.5%) versus controls (1.0%, p = 0.02).35 However, all patients who bled on clopidogrel were concomitantly using aspirin, and clopidogrel alone was not found to be an independent risk factor for postpolypectomy bleeding. The other study found no increased risk for postpolypectomy bleeding in clopidogrel patients versus controls, but had a very low overall event rate.36 Patients with expandable metal coronary stents are at significant risk for thrombosis, particularly in the first 30 days after placement, and this likely represents the most common indication for thienopyridine therapy.37 In these patients, efforts should be made not to interrupt thienopyridine therapy until the minimum recommended treatment interval has been completed.38 This may be accomplished by avoiding or delaying ES (e.g., placing a temporary biliary stent for a bile leak or bile duct stone). If ES cannot be delayed, considerations include withholding the thienopyridine yet continuing (or starting) aspirin to minimize thrombotic risk, or continuing thienopyridine monotherapy.

Anticoagulants

In a prospective multicenter study both coagulopathy prior to ES and resumption of anticoagulation within 3 days following ES were found to be risk factors for post-ES bleeding.33 In patients in whom reversal of coagulopathy is difficult or undesirable, alternatives to ES may be considered (e.g., balloon sphincteroplasty). However, if ES is necessary, patients should have warfarin discontinued 3 to 5 days prior to ES. In patients at high risk for thrombosis, bridging therapy with unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) may be appropriate once the INR is <2. High-risk conditions for thromboembolic events include complicated atrial fibrillation (e.g., atrial fibrillation associated with valvular heart disease or prosthetic valves), a mechanical valve in the mitral position, and a recently placed coronary stent, among others. A more complete enumeration of high- and low-risk conditions for thromboembolism can be found in the ASGE guideline “Management of Antithrombotic Agents for Endoscopic Procedures.”26 UFH should be held for 4 hours and LMWH held for 12 to 24 hours prior to ES.39–41 Anticoagulation should be resumed when safely possible; in the absence of immediate bleeding adverse events, UFH should be reinitiated 2 to 6 hours after ERCP and warfarin should be resumed within 24 hours after the procedure.

Dabigatran etexilate and rivaroxaban are newer oral anticoagulants that inhibit thrombin and factor Xa, respectively, and are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to reduce the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Fondaparinux sodium is a subcutaneously administered factor Xa inhibitor that is FDA-approved for postsurgical venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, as well as treatment for acute deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. There are no data regarding the safety of ERCP with ES in patients taking these agents, and best practices regarding preprocedural discontinuation must be derived from pharmacokinetic data and recommendations from the pharmaceutical manufacturers. The package insert for dabigatran recommends discontinuation 1 to 2 days before a procedure if the estimated creatinine clearance (Clcr) is 50 mL/min or greater, or 3 to 5 days before a procedure if Clcr is less than 50 mL/min, based on the half-life (12 to 17 hours) and predominant renal clearance of the drug.42 Rivaroxaban has a shorter half-life (5 to 9 hours) and less renal clearance than dabigatran; therefore withholding the drug for 24 hours prior to ERCP appears to be appropriate.43 Fondaparinux has a much longer half-life (17 to 21 hours) than LMWHs and the manufacturer’s insert warns that its anticoagulant effects may persist for 2 to 4 days in patients with normal renal function (i.e., at least 3 to 5 half-lives), and potentially even longer in patients with renal impairment.44

Duration of Fasting

Patients should be instructed to avoid solid food for 6 to 8 hours and clear liquids for 1 to 2 hours prior to ERCP in order to maximize safety (i.e., reduce risk for aspiration) and endoscopic visualization.45–47 In patients with known delayed gastric emptying and those with suspected gastric outlet obstruction, a longer duration of fasting and/or passage of a nasogastric sump tube may be appropriate prior to the procedure.

Method of Sedation, Proper Personnel, and Patient Monitoring

Selecting Sedation for ERCP

ERCP may be safely and successfully performed using moderate sedation (e.g., midazolam and meperidine) or deep sedation (e.g., propofol) and with general anesthesia. Factors influencing the method for anesthesia delivery include patient factors (age, body habitus, comorbidities), procedure factors (complexity, duration, risk), and availability and expertise of anesthesia providers. ERCP sedation is discussed in detail in Chapter 5; however, a few salient points bear mention in relation to planning and preparation for ERCP sedation.

Two large prospective cohort studies of patients undergoing ERCP with monitored anesthesia care (MAC; typically comprising propofol with or without low-dose midazolam and narcotic) identified increased body mass index (BMI) and an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score of 3 or higher as risk factors for sedation-related adverse events (SRAEs).48,49 The most common SRAEs in this setting are respiratory (e.g., hypoxemia), and may require airway maneuvers (AMs) such as chin lift, nasal airway placement, or even endotracheal intubation. Another prospective cohort study demonstrated that advancing degrees of obesity were associated with incrementally higher risks for SRAEs and need for AMs during ERCP with MAC; patients with a BMI >35 were at greatest risk and required AMs in 27% of cases.50 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) frequently complicates obesity and may portend an even higher risk for SRAEs and AMs. In a prospective study that used a validated screening tool for OSA (the STOP-BANG assessment) in patients undergoing ERCP with MAC, 20% of patients who were at high risk for OSA required AMs, while only 6% of low-risk patients required AMs.51 Thus patients with an ASA score ≥3, increased BMI (>30), or known or predicted OSA are at higher risk for SRAEs during ERCP and consideration should be given to anesthesia support in these patients.

A large retrospective study of patients undergoing ERCP with midazolam and meperidine confirmed that patients using chronic narcotics or benzodiazepines required higher doses of sedation; however, this subset was not associated with a higher risk for SRAEs.52 In this study, age greater than 80 years, higher doses of meperidine, and the adjunctive use of promethazine were risk factors for the need for reversal agents. The immediate availability of flumazenil and naloxone should be confirmed prior to commencing any ERCP in which intravenous narcotics and benzodiazepines are used.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree