Plug and Patch Inguinal Hernia Repair

Jonathan F. Critchlow

Introduction

Inguinal hernia repair is one of the most common operations performed by general surgeons, with approximately 750,000 operations done per year in the United States by surgeons who incorporate it as a part of their varied practices. Conventional open repairs without prosthetics are most often successful for small hernias. However, they are plagued in general by a high recurrence rates except in specialized centers. This has prompted most surgeons in the United States to turn to prosthetics which have the following advantages:

Less tension

Utility in areas where there is poor tissue strength

Strengthening other weak areas of the floor at the time of operation

Coverage of the areas which may deteriorate over time

Attention to all of the above have led to lower recurrence rates with the use of grafts. The quest has continued for a prosthetic repair which is rapid, safe, versatile, and easily taught. The patch/plug repair has thus been embraced by a large number of surgeons as their procedure of choice.

The open preperitoneal approach described by Stoppa is quite effective but involves extensive dissection in often somewhat unfamiliar anatomy. It is now relegated to complex hernias and recurrences. The anterior approach was addressed by Lichtenstein, whose work revolutionized herniorrhaphy in the United States. However, this technique, which reinforces the entire floor of the inguinal canal without directly addressing the defect, requires a meticulous closure with continuous sutures, and does expose the patient to some risk of recurrence through small gaps in the external repair, or because the primary defect has not been bridged.

Gilbert described the “sutureless” repair which was preperitoneal placement of a mesh patch to close the defect of an indirect hernia with an overlay similar to that of Lichtenstein, but without sutures as the original defect had been addressed. Direct hernia defects were bridged with a round plug followed by an overlay to reinforce the floor and help to hold the plug in place. Rutkow and Robbins developed an approach to repair the primary defect with a prosthetic material (“plug”) and resurfacing the

entire floor with mesh to prevent recurrence and to help hold the plug in place. This approach is applicable to direct and indirect hernias and has enjoyed tremendous success and is arguably the most common repair done in the United States. It can be done quickly and efficiently under local anesthesia with or without sedation, allowing for safe repair in high risk patients with low recurrence rates. This is a very versatile technique and is adaptable to most all types of hernias including the findings of an unsuspected femoral hernia or Pantaloon hernias. It is rapid and can most often be done as an outpatient without general anesthesia. Some have argued that this is a more “minimally invasive” approach to hernia repair than laparoscopy as it can be done without general anesthesia, bladder catheterization, or extensive dissection violating the space of Retzius around the bladder and prostate which could complicate subsequent prostatectomy. Some surgical educators bemoan the fact that this relatively simple technique does not require the more extensive skill and understanding of complex anatomy on the part of the trainee to complete a successful repair as compared to tissue repairs and that future surgeons are not as prepared to handle the unusual contaminated case. This can be considered, but countered by excellent patient outcomes and that the fine points of anatomy are often lost on the most junior trainees who do the majority of these operations during residency. This technique has allowed hernia repair to truly become an “intern-case”.

entire floor with mesh to prevent recurrence and to help hold the plug in place. This approach is applicable to direct and indirect hernias and has enjoyed tremendous success and is arguably the most common repair done in the United States. It can be done quickly and efficiently under local anesthesia with or without sedation, allowing for safe repair in high risk patients with low recurrence rates. This is a very versatile technique and is adaptable to most all types of hernias including the findings of an unsuspected femoral hernia or Pantaloon hernias. It is rapid and can most often be done as an outpatient without general anesthesia. Some have argued that this is a more “minimally invasive” approach to hernia repair than laparoscopy as it can be done without general anesthesia, bladder catheterization, or extensive dissection violating the space of Retzius around the bladder and prostate which could complicate subsequent prostatectomy. Some surgical educators bemoan the fact that this relatively simple technique does not require the more extensive skill and understanding of complex anatomy on the part of the trainee to complete a successful repair as compared to tissue repairs and that future surgeons are not as prepared to handle the unusual contaminated case. This can be considered, but countered by excellent patient outcomes and that the fine points of anatomy are often lost on the most junior trainees who do the majority of these operations during residency. This technique has allowed hernia repair to truly become an “intern-case”.

Elective repair of most all indirect and direct hernias

Emergent repair of most all indirect and direct hernias without contamination

Hernia repair in patients unable to tolerate general anesthesia

Bilateral inguinal hernia repairs—patient preference

Strangulated hernias with gangrene

Wound contamination

Asymptomatic hernias in very high risk patients

Multiple recurrent hernias previously repaired via an anterior approach

If possible, antiplatelet medications and anticoagulants should be held. Aspirin should be stopped 10 days prior to the date of operation unless essential for prevention of serious coronary or vascular events. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be discontinued 24 to 48 hours prior to operation. Warfarin is held in patients who are at low to moderate risk for thromboembolism. It may be continued at a lower dose to effect an international normalized ratio (INR) of approximately 2.0 in patients of moderate risk, and most often the operation may be performed easily without the need for a heparin “bridge”. Prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis is generally not necessary as most patients are done under sedation with local anesthesia unless general anesthesia is used in a patient at very high risk. These repairs are generally done under local anesthesia with sedation delivered by an anesthesiologist. Repair of hernias which are very large, recurrent or those in uncooperative patients are done under general anesthesia. Intravenous antibiotics with good gram-positive coverage are administered, as graft material is implanted. An alcohol-based antiseptic (e.g., chlorhexidine) is used to prepare the skin as it is more bacteriocidal than povidone-iodine.

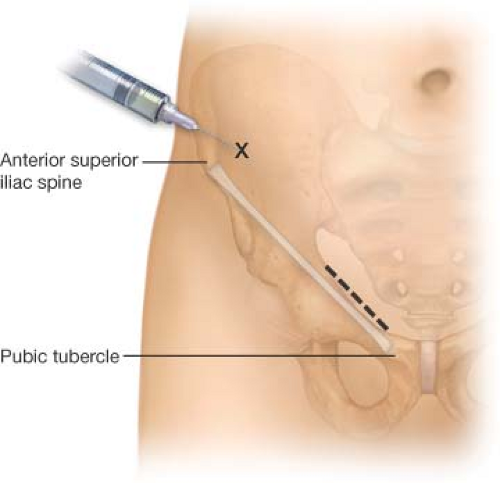

A mixture of 0.5% xylocaine and 0.5% bupivacaine is infiltrated locally. This is used throughout the procedure prior to incision of each fascial layer. A nerve block is also helpful for intraoperative anesthesia and postoperative analgesia. This is placed 2 cm medially and superior to the anterior superior iliac spine. A blunted 22 gauge needle is used so that a “pop” can be felt as the needle penetrates through the external oblique fascia thus delivering the solution in the appropriate layer (Fig. 3.1).

A 4 to 6 cm oblique incision is made beginning at the pubic tubercle and extending toward the internal ring (Fig. 3.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree