Chapter 76 PERINEAL HERNIA AND PERINEOCELE

Perineal hernia is an uncommon condition that was once thought to be incurable because of the difficulty in closing the hernia defect and the high recurrence rate.1 The past century witnessed the development of a plethora of techniques to repair perineal hernias and an improved understanding of the anatomic defects, leading to their classification. Despite the knowledge gained, much remains to be discovered about perineal hernias. There are no controlled studies to guide the clinician in the choice of optimal therapy. Perineocele is an even less studied and less well-defined clinical problem. Both conditions are discussed in this chapter.

PERINEAL HERNIA

Definition and Classification

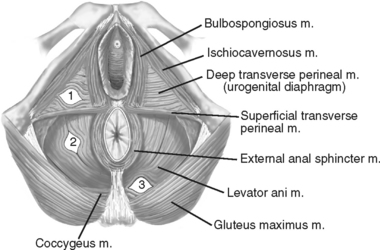

Herniation can occur through the anterior or posterior compartments of the pelvic floor. Anterior perineal hernias (i.e., pudendal hernias, pudendal enteroceles, or levator hernias) occur within the urogenital triangle anterior to the superficial transverse perineal muscles, and they occur exclusively in women; no confirmed cases in men have been reported. Anterior perineal hernias occur through the urogenital diaphragm within the triangular regions lateral to each side of the vaginal vestibule defined by the medial border of the ischiocavernosus muscle, the lateral border of the bulbocavernosus muscle, and the anterior border of the superficial transverse perineal muscle (Fig. 76-1). Posterior perineal hernias occur in within the anal triangle posterior to the superficial transverse perineal muscles and anterior to the ventral borders of the gluteus maximus muscles. They typically occur midway between the anus and the ischial tuberosity within a levator ani defect, in the space between the pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus portions of the levator ani muscle, or in the space between the levator ani and coccygeus muscles (see Fig. 76-1).

Figure 76-1 Anatomy of perineum and typical locations of perineal hernias.

(Modified from Cali RL, Pitsch RM, Blatchford GJ, et al: Rare pelvic floor hernias. Dis Colon Rectum 35:604, 1992.).

Translevator and supralevator hernias are anatomically distinct.2 A translevator perineal hernia sac passes through the focal defect within the levator ani musculature, whereas a supralevator hernia sac remains superior to the levator ani but exists as a focal outpouching of the weakened levator ani muscle that extends beyond the plane of the levator plate. Despite the anatomic difference, the principles of hernia repair remain the same.

The hernia sac of a perineal hernia may be empty (i.e., peritoneum) or may contain one or more of the abdominopelvic viscera, including small or large bowel, bladder, omentum, ovary, and fallopian tube. Because intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal structures may herniate, a true hernia sac may not always be present.1

Etiology and Epidemiology

Anterior perineal hernias can be primary or secondary (i.e., after surgery or obstetric procedures). Anterior perineal hernias are rare, with fewer than 17 well-described cases in the English literature.1,3–6 Most reported perineal hernias are posterior perineal hernias. The largest reported series of anterior perineal hernias is that of Chase in 1922, reporting 13 cases.1 However, only 10 of these 13 cases were described in enough detail to be confirmed cases of anterior perineal hernia. All of the well-described cases of anterior perineal hernia appear to have occurred in the setting of multiple prior pelvic operations for pelvic prolapse or urinary incontinence or of difficult and prolonged labor, often requiring forceps delivery. Both causes involve direct trauma to the pelvic floor musculature, which is thought to be the primary cause of anterior perineal hernias. Most anterior perineal hernias are secondary.

Posterior perineal hernias may be primary or secondary. Primary perineal hernias are rare, and their true incidence is unknown. They typically occur between the ages of 40 and 60 years, and they occur more commonly in women, with a female preponderance of threefold to fivefold higher than for men.7,8 This female preponderance is attributed to female pelvic floor trauma encountered during childbirth9 and the phenomenon of pelvic relaxation.10 A study by Gearhart and colleauges10 demonstrated a 15% incidence of levator ani hernia in a group of 80 patients who underwent dynamic pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the evaluation of symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Forty-two percent of these patients had undergone prior pelvic surgery, and approximately 60% (or 9% of the entire group) are presumed to be primary levator ani hernias associated with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Other conditions are also thought to contribute to the formation of primary perineal hernia, including recurrent pelvic floor infections and conditions involving increased abdominal pressure such as chronic cough, chronic constipation, obesity, and ascites (Table 76-1).8,11,12

Table 76-1 Risk Factors for Perineal Hernias

Secondary posterior perineal hernias occur through defects in the pelvic floor resulting from surgery, and they usually manifest within 1 year after the initial surgery.9 Most secondary perineal hernias occur after pelvic exenterative surgery, requiring corrective surgery after approximately 0.7% of abdominoperineal resections13 and 3% of pelvic exenterations.14 The true incidence of perineal hernia after these procedures is likely higher, and most are asymptomatic. Hullsiek15 found a 7% incidence of perineal hernia after abdominoperineal resection by means of barium x-ray films, and most were asymptomatic.

Secondary posterior16 and anterior3,5,6 perineal hernias have been reported after surgery for pelvic prolapse and urinary incontinence. However, their overall incidence after prolapse and incontinence surgery is unknown. It is difficult to determine whether these hernias result from the prolapse surgery or the pathophysiologic process of pelvic prolapse itself. Presumably, it is a combination of both because a significant proportion (42%) of perineal hernias associated with symptomatic pelvic prolapse occur in the absence of a history of pelvic surgery.10

Table 76-1 summarizes the types of operations associated with secondary perineal hernias. Poor perineal tissue quality and factors that hinder wound healing such as diabetes and pelvic irradiation also predispose to perineal hernia. One of the most significant predisposing factors for perineal hernia after abdominoperineal resection was found to be a partial or complete open perineal wound in the postoperative period.17

Symptoms and Clinical Findings

Anterior perineal hernia typically manifests as a reducible labial mass, usually in the posterior aspect of the labia majora. This may be accompanied by a heavy sensation within the perineum.4 The mass is characteristically covered with vaginal mucosa on its medial border and the labial integument on its lateral border. An anterior perineal hernia is also characteristically reducible into the pelvic floor medial and inferior to the pubic ramus, whereas an inguinal hernia within the labia reduces into the inguinal canal by crossing over the pubic ramus. The reducibility of the hernia also distinguishes it from irreducible labial masses such as Bartholin’s gland abscesses or cysts, benign labial cysts, labial lipomas and sarcomas, and labial hematomas (Table 76-2). Careful vaginal and perineal examination is needed to avoid inadvertent incision into a perineal hernia that many contain bladder or bowel.

Table 76-2 Differential Diagnosis of Perineal Hernia

| Diagnosis | Clinical Features |

|---|---|

| Anterior perineal masses | |

| Anterior perineal hernia | Labial mass reduces into pelvic floor medial to pubic ramus |

| Inguinal hernia | Labial mass reduces into inguinal canal across pubic ramus |

| Bartholin gland abscess | Labial mass irreducible, fluctuant, signs of inflammation |

| Lipoma or sarcoma | Labial mass, irreducible |

| Hematoma | Labial mass, irreducible, history or signs of perineal trauma |

| Cystocele, rectocele, enterocele | Introital mass, associated urinary or fecal symptoms |

| Posterior perineal masses | |

| Posterior perineal hernia | Soft, reducible, posterior to perineum |

| Sciatic hernia | Emerges on inferior border of gluteus maximus |

| Rectal prolapse | Emerges from anus, associated constipation or fecal incontinence |

| Perineocele | Pelvic descent, increased anovaginal distance |

It is not uncommon for anterior perineal hernias to contain bladder because defects within the anterior pelvic floor more often contain bladder.3 This can result in urinary sequelae, including urinary incontinence, weak urinary stream, and incomplete bladder emptying with high postvoid residual volumes.4,6 Patients with concurrent urinary symptoms should undergo diagnostic cystoscopy and imaging of the lower urinary tract.

Posterior perineal hernias typically manifest as soft, reducible masses within the posterior perineum (posterior to the perineal body), usually occurring in the region between the anus and ischial tuberosity, but they may also emerge just ventral to the gluteus maximus, in which case they must be distinguished from a sciatic hernia, which is rare.12 They are often asymptomatic,10 but they may be accompanied by a heavy or dragging feeling within the perineal region and pain with sitting.

Perineal hernias usually do not incarcerate or strangulate because the pelvic floor defect is often large and the hernia remains easily reducible. However, there are reports of postoperative perineal hernia that have been accompanied by bowel obstruction and perineal skin breakdown.18,19 Often, the bowel obstruction is intermittent and occurs because of bowel compression when the patient is sitting.

Evaluation

Plain radiographs of the pelvis and barium enema are able to demonstrate bowel within the hernia sac.20 Dynamic proctography, typically used to evaluate defecatory dysfunction, is able to demonstrate the extent and involved segment of perineal rectal herniation.7 The presumed advantage over barium enema is applicable for cases in which the perineal herniation occurs only during straining and defecation. CT evaluation of the pelvic floor is more definitively able to identify the contents of the hernia sac and the location and extent of the associated pelvic floor defect.11

MRI is gaining acceptance as a preferred method of evaluation of the pelvic floor because of its excellent resolution of pelvic floor21,22 and perianal23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree