Pelvic floor muscles have two major functions: they provide support or act as a floor for the abdominal viscera including the rectum; and they provide a constrictor or continence mechanism to the urethral, anal, and vaginal orifices (in females). This article discusses the relevance of pelvic floor to the anal opening and closure function, and discusses new findings with regards to the role of these muscles in the vaginal and urethra closure mechanisms.

Pelvic floor muscles have two major functions: they provide support or act as a floor for the abdominal viscera including the rectum; and they provide constrictor or continence mechanism to the urethral, anal, and vaginal orifices (in females). This article discusses the relevance of pelvic floor to the anal opening and closure function, and discusses new findings with regards to the role of these muscles in the vaginal closure mechanisms.

The bony pelvis is composed of sacrum, ileum, ischium, and pubis. It is divided into the false (greater) and true (lesser) pelvis by the pelvic brim. The sacral promontory, the anterior ala of the sacrum, the arcuate line of the ilium, the pectineal line of the pubis, and the pubic crest that culminates in the symphysis pubis, mark the pelvic brim. The shape of the female bony pelvis can be classified into four broad categories: (1) gynecoid, (2) anthropoid, (3) android, and (4) platypelloid. The pelvic diaphragm is a wide but thin muscular layer of tissue that forms the inferior border of the abdominopelvic cavity. Composed of a broad, funnel-shaped sling of fascia and muscle, it extends from the symphysis pubis to the coccyx and from one lateral sidewall to the other. The urogenital diaphragm, also called the “triangular ligament,” is a strong, muscular membrane that occupies the area between the symphysis pubis and ischial tuberosities and stretches across the triangular anterior portion of the pelvic outlet. The pelvic ligaments are not classic ligaments but are thickenings of retroperitoneal fascia and consist primarily of blood and lymphatic vessels, nerves, and fatty connective tissue. Anatomists call the retroperitoneal fascia “subserous fascia,” whereas surgeons refer to this fascial layer as “endopelvic fascia.” The connective tissue is denser immediately adjacent to the lateral walls of the cervix and the vagina. The broad ligaments are a thin, mesenteric-like double reflection of peritoneum stretching from the lateral pelvic sidewalls to the uterus. The cardinal, or Mackenrodt’s, ligaments extend from the lateral aspects of the upper part of the cervix and the vagina to the pelvic wall. The uterosacral ligaments extend from the upper portion of the cervix posteriorly to the third sacral vertebra.

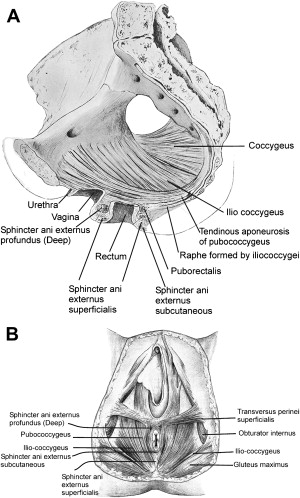

The pelvic floor is comprised of a number of muscles and they are organized into superficial and deep muscle layers. There is significant controversy with regards to the nomenclature, but generally speaking the superficial muscle layer and the muscles relevant to the anal canal function are the external anal sphincter (EAS), perineal body, and possibly the puboperineal (or transverse perinei) muscles ( Fig. 1 ). The deep pelvic floor muscles consist of pubococcygeus, ileococcygeus, coccygeus, and puborectalis muscles. Puborectalis muscle is located in between the superficial and deep muscle layers, and it is better to view this as the middle muscle layer of the pelvic floor. In addition to the skeletal muscles of the pelvic floor, caudal extension of the circular and longitudinal smooth muscles from the rectum into the anal canal constitutes the internal anal sphincter (IAS) and EAS of the anal canal, respectively. Discussed are the salient and the controversial aspects of anatomy of the pelvic floor and anal sphincter muscles, followed by a discussion of the function of each component of the pelvic floor muscles and their role in anal sphincter closure and opening.

Anatomic considerations

Internal Anal Sphincter

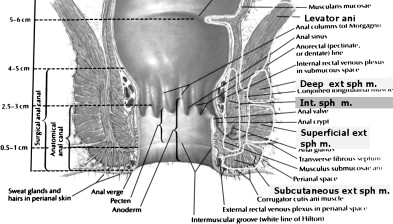

Circular muscle layer of the rectum expands caudally into the anal canal and becomes the IAS. The circular muscles in the sphincteric region are thicker than those of the rectal circular smooth muscle with discrete septa in between the muscle bundles. Similarly, the longitudinal muscles of the rectum extend into the anal canal and end up as thin septa that penetrate into the puborectalis and EAS muscles. Longitudinal muscle of the anal canal is also referred to as the “conjoined tendon” (muscle) because some authors believe that skeletal muscles of the pelvic floor (puboanalis) join the smooth muscles of the rectum to form a conjoint tendon. Immunostaining for the smooth and skeletal muscles in this region shows, however, that the smooth muscles make up the entire longitudinal muscle layer of the anal canal.

The autonomic nerves, sympathetic (spinal nerves) and parasympathetic (pelvic nerves), supply the IAS. Sympathetic fibers originate from the lower thoracic ganglia to form the superior hypogastric plexus. Parasympathetic fibers originate from the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th sacral nerves to form the inferior hypogastric plexus, which in turn gives rise to superior, middle, and inferior rectal nerves that ultimately supply the rectum and anal canal. These nerves synapse with the myenteric plexus of the rectum and anal canal. Most of the tone of the IAS is myogenic (ie, caused by unique properties of the smooth muscle itself). Angiotensin 2 and prostaglandin F 2α play modulatory roles. Sympathetic nerves mediate IAS contraction through the stimulation of α and relaxation through β 1, β 2 , and β 3 adrenergic receptors. Recent studies show a predominance of low affinity β 3 receptors in the IAS. Stimulation of parasympathetic or pelvic nerves causes IAS relaxation through nitric oxide–containing neurons located in the myenteric plexus. Vasointestinal intestinal peptide and carbon monoxide are other potential inhibitory neurotransmitters of the inhibitory motor neurons but most likely play limited roles. There are also excitatory motor neurons in the myenteric plexus of IAS and the effects of these neurons are mediated through acetylcholine and substance P. Some investigators believe that the excitatory and inhibitory effects of myenteric neurons on the smooth muscles of IAS are mediated through the Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), but other investigators do not necessarily confirm these findings. Degeneration of myenteric neurons resulting in impaired IAS relaxation is the hallmark of Hirschsprung’s disease.

External Anal Sphincter

In his original description of 1769, Santorini stated that EAS has three separate muscle bundles: (1) subcutaneous, (2) superficial, and (3) deep. Large numbers of publications continue to show EAS to be made up of these three components. Several investigators have found, however, that the subcutaneous and superficial muscle bundles only constitute the EAS. The subcutaneous portion of the EAS is located caudal to the IAS and the superficial portion surrounds the distal part of IAS. The deep portion of the EAS is either very small and merges imperceptibly with the puborectalis muscle, or in the authors’ opinion has been confused with the puborectalis muscle. In several schematics published in the literature, including the one by Netter ( Fig. 2 ), the EAS is made of three components. A close inspection of these schematics reveals that the puborectalis muscle is entirely missing from these drawings. Based on three-dimensional ultrasound (US) and MRI, the authors believe that the puborectalis muscle is actually the deepest part of the EAS. Shafik described that the EAS consists of three loops; the puborectalis muscle forms the top loop in his drawing ( Fig. 3 ). Histologic studies by Fritsch and coworkers and the MRI imaging study of Stoker and colleagues ( Fig. 4 ) are quite convincing that the EAS muscle is composed of only the subcutaneous and superficial portions. Anteriorly, the EAS is attached to the perineal body and transverse perinei muscle, and posteriorly to the anococcygeal raphae. EAS, however, is not a circular muscle in its entirety; rather, it is attached to the transverse perinei (also called “puboperineal”) muscle on either side. The posterior wall of the EAS is shorter in its craniocaudal extent than the anterior wall. This should not be misconstrued as a muscle defect in the axial US and MRIs of the lower anal canal. Another implication of this peculiar anatomy is when the anal canal pressure is measured using circumferential side holes; the posterior side holes exit first from the anal canal, thereby causing apparent circumferential asymmetry of the anal canal pressures. The muscle fibers of EAS are composed of fast and slow twitch types, which allow it to maintain sustained tonic contraction at rest and also to contract rapidly with voluntary squeeze. Motor neurons in Onuf’s nucleus (located in the sacral spinal cord) innervate EAS muscle through the inferior rectal branches of the right and left pudendal nerves.

Puborectalis and deep pelvic floor muscles

In 1555, Vesalius wrote an account of the pelvic floor muscles, which he named “musculus sedem attollens.” This was later replaced by the more definitive name of “levator ani” by Von Behr and coworkers. The pelvic diaphragm, first so named in 1861 by Meyer, included primitive flexors and abductors of the caudal part of the vertebral column. These muscles included coccygeus (also referred to as “ischiococcygeus”), ileococcygeus, and pubococcygeus and these three muscles were believed to constitute the levator ani muscle. They originate from the pectinate line of the pubic bone and the fascia of the obturator internus muscle and are inserted into the coccyx. Holl, a German anatomist, in 1897 described that some of the pubococcygeus muscle fibers, instead of inserting into the coccyx, looped around the rectum and to these fibers he assigned the name “puborectalis” or “sphincter recti.” It seems that the puborectalis muscle originates from the middle of inferior pubic rami rather than from the pubic symphysis. The puborectalis muscle is now included in the levator ani muscle group and the term “levator ani” is used synonymously with pelvic diaphragm muscles. Thompson in a classic text on this subject, quoted Sappey, writing that “the levator ani is one of those muscle which has been studied the most, and at the same time one about which we know the least.” Sappey also stated that the “The doctrine of continuity of fibers between two or more muscles of independent actions has been applied to the levator ani at various scientific epochs, and this ancient error, renewed without ceasing, has singularly contributed to complicate its study.” It is interesting that to this date the nomenclature, anatomy, neural innervation, and functions of the levator ani and pelvic diaphragm are still veiled in deep mystery. Based on anatomic dissection studies, the pubococcygeus, puborectalis, and puboperineal muscles originate from the pubic bone and are difficult to differentiate from each other. These muscles have also been collectively called the “pubovisceralis muscle,” a concept originally championed by Lawson and currently supported by Delancey in most of his writings. The term pubovisceral muscle is well accepted in the urogynecologic texts; however, it is rarely mentioned in the anatomic textbooks or gastroenterology literature. Lawson believed that the portions of the pubovisceral muscle are inserted into the urethra, vagina, perineal body, and anal canal and to those portions he assigned the names pubouretheralis, pubovaginalis, puboperinealis, and puboanalis muscles, respectively. According to Lawson, the major function of these muscles is to provide physical support to the visceral organs.

Branches from the sacral nerve roots of S2, S3, and S4 innervate the pelvic floor muscles. There is considerable controversy, however, as to whether the pudendal nerves actually innervate the levator ani muscles. An electrophysiologic study by Percy and colleagues found the electrical stimulation of the pudendal nerve did not activate the puborectalis muscle. It is possible, however, that in their study the electrodes may not have been precisely located in the puborectalis portion of the levator ani muscle. The authors’ opinion is that the puborectalis muscle (middle layer of pelvic floor muscle) is actually innervated by the pudendal nerve (from below) and the deep muscles (pubococcygeus, ileococcygeus, and coccygeus) are innervated by the direct branches of sacral nerve roots S3 and S4. The significance is that pudendal nerve damage may cause dysfunction of puborectalis muscle and EAS muscles (both constrictor muscles) and this in turn may cause fecal incontinence.

Puborectalis and deep pelvic floor muscles

In 1555, Vesalius wrote an account of the pelvic floor muscles, which he named “musculus sedem attollens.” This was later replaced by the more definitive name of “levator ani” by Von Behr and coworkers. The pelvic diaphragm, first so named in 1861 by Meyer, included primitive flexors and abductors of the caudal part of the vertebral column. These muscles included coccygeus (also referred to as “ischiococcygeus”), ileococcygeus, and pubococcygeus and these three muscles were believed to constitute the levator ani muscle. They originate from the pectinate line of the pubic bone and the fascia of the obturator internus muscle and are inserted into the coccyx. Holl, a German anatomist, in 1897 described that some of the pubococcygeus muscle fibers, instead of inserting into the coccyx, looped around the rectum and to these fibers he assigned the name “puborectalis” or “sphincter recti.” It seems that the puborectalis muscle originates from the middle of inferior pubic rami rather than from the pubic symphysis. The puborectalis muscle is now included in the levator ani muscle group and the term “levator ani” is used synonymously with pelvic diaphragm muscles. Thompson in a classic text on this subject, quoted Sappey, writing that “the levator ani is one of those muscle which has been studied the most, and at the same time one about which we know the least.” Sappey also stated that the “The doctrine of continuity of fibers between two or more muscles of independent actions has been applied to the levator ani at various scientific epochs, and this ancient error, renewed without ceasing, has singularly contributed to complicate its study.” It is interesting that to this date the nomenclature, anatomy, neural innervation, and functions of the levator ani and pelvic diaphragm are still veiled in deep mystery. Based on anatomic dissection studies, the pubococcygeus, puborectalis, and puboperineal muscles originate from the pubic bone and are difficult to differentiate from each other. These muscles have also been collectively called the “pubovisceralis muscle,” a concept originally championed by Lawson and currently supported by Delancey in most of his writings. The term pubovisceral muscle is well accepted in the urogynecologic texts; however, it is rarely mentioned in the anatomic textbooks or gastroenterology literature. Lawson believed that the portions of the pubovisceral muscle are inserted into the urethra, vagina, perineal body, and anal canal and to those portions he assigned the names pubouretheralis, pubovaginalis, puboperinealis, and puboanalis muscles, respectively. According to Lawson, the major function of these muscles is to provide physical support to the visceral organs.

Branches from the sacral nerve roots of S2, S3, and S4 innervate the pelvic floor muscles. There is considerable controversy, however, as to whether the pudendal nerves actually innervate the levator ani muscles. An electrophysiologic study by Percy and colleagues found the electrical stimulation of the pudendal nerve did not activate the puborectalis muscle. It is possible, however, that in their study the electrodes may not have been precisely located in the puborectalis portion of the levator ani muscle. The authors’ opinion is that the puborectalis muscle (middle layer of pelvic floor muscle) is actually innervated by the pudendal nerve (from below) and the deep muscles (pubococcygeus, ileococcygeus, and coccygeus) are innervated by the direct branches of sacral nerve roots S3 and S4. The significance is that pudendal nerve damage may cause dysfunction of puborectalis muscle and EAS muscles (both constrictor muscles) and this in turn may cause fecal incontinence.

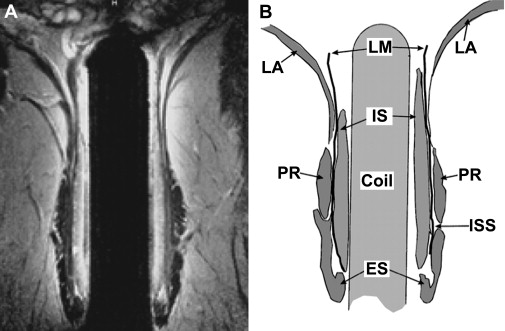

Pelvic floor imaging

Advances in MRI, CT scanning, and three-dimensional US imaging have provided novel insights into the anatomy and function of the pelvic floor muscles. Ultrafast CT scanning can image dynamic changes in the pelvic floor muscle during contraction and defecation. These studies reveal that the levator hiatus becomes smaller during pelvic floor contraction and larger during the act of defecation ( Fig. 5 ). The changes in the pelvic floor hiatus size are predominantly related to the puborectalis muscle and they reflect the constrictor function of pelvic floor. The ascent (elevation) and descent of the pelvic floor, however, including the levator plate, is mostly likely related to the contraction and relaxation of the pubococcygeus, ileococcygeus, and ischiococcygeus muscles.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree