Biofeedback as delivered in most clinical settings in Western medicine has been consistently reported to improve symptoms of fecal incontinence. Closer scrutiny of the elements of the intervention and controlled studies, however, have consistently failed to find any benefit of the biofeedback element of this complex package of care; nor has any superiority been found for one modality over another. There is a need for further well-designed and adequately powered randomized controlled trials. Meanwhile, there can be little doubt that conservative interventions improve many patients with fecal incontinence to the point where most report satisfaction with treatment and do not wish to consider more invasive options, such as surgery.

Fecal incontinence (FI) may be defined as involuntary loss of stool that is a social or hygienic problem. It affects between 1% and 15% of adults to at least some extent, depending on the definition used, and is probably a significant limitation on quality of life for 0.5% to 1% of adults. Although FI increases in prevalence with advancing age and disability, it also affects large numbers of healthy adults in middle age. Somewhat surprisingly, in most large community studies the prevalence in men and women is similar, although women tend to have more severe and frequent symptoms, and certainly present more often for clinical care.

FI has an understandably profound impact on a patient’s quality of life, leading to major social and psychologic impact in many cases. As a stigmatized condition, it leads to embarrassment and shame, often combined with reluctance to admit the problem and present for help from health care professionals. Some people lack a vocabulary with which to explain their symptoms, or assume that FI is an inevitable consequence of childbirth, diarrheal disease, or anal surgery. The impact seems to be very individual, and some cope well, but others live in fear of being caught out in public and map all activities around the likely availability of easy access to toilet facilities. Increasing recognition of the importance of the patient perspective and impact on quality of life has led to recent efforts to develop standardized and validated tools to add this dimension to outcome measures for FI, in addition to the somewhat simplistic “scores” that presume that number of episodes equate to “severity”. Those patients with the most severe symptoms and impact on quality of life are the most likely to seek help.

FI is a symptom arising from diverse etiologies, which often coexist in the same individual. Typically, patients complain of urgency and urge incontinence, often indicating external sphincter weakness or damage, or passive soiling secondary to internal anal sphincter disruption or atrophy. Both symptoms can be present in the same individual. Stool consistency, bowel motility, sensation, completeness of evacuation, and physical or mental abilities for self-care may each have an impact. The most common causes and contributing factors are summarized in Table 1 .

| External sphincter disruption or internal sphincter disruption | Obstetric injury; congenital anomaly; iatrogenic following colorectal surgery (eg, hemorrhoidectomy or sphincterotomy); impalement injuries; idiopathic degeneration |

| Diarrhea or loose stool | Inflammatory bowel disease; irritable bowel syndrome; gastrointestinal infections; dietary sensitivities (eg, lactose or fructose intolerance, caffeine sensitivity, excess alcohol, artificial sugars); medications (eg, orlistat, antibiotics); celiac disease; anxiety; radiation enteropathy |

| Loss of sensation | Neurologic disease or injury (eg, spinal cord injury, spina bifida, multiple sclerosis, diabetic neuropathy) |

| Constipation or incomplete evacuation | Frailty, immobility, stool impaction, rectocele or pelvic floor dysfunction, neurologic disease or injury, medications |

| Anorectal pathology | Rectal prolapse, third-degree hemorrhoids, anal fistula |

| Physical disabilities with toileting difficulties | Neurologic disease or injury, frail elderly people, poor toileting facilities, lack of caregiver availability |

| Mental capacity to comply with social norms for toilet behavior | Severe learning difficulties, confusion, advanced dementia |

| Idiopathic | Cause unknown |

It is this multiple pathology that often enables FI symptoms to be reversed by conservative means. Even in patients with sphincter trauma, there may well be an element of residual function that can be improved, or other factors, such as stool consistency, toilet habit, complete evacuation, psychologic coping, and toilet access, can be optimized. In practice, although sphincter damage is commonly found when these patients are imaged, careful history often reveals that the patient has not been symptomatic continuously following the trauma incident. Other factors have contributed to symptom development, and these can be modified.

Patient assessment

Because FI is a symptom of multiple etiologies, it is highly unlikely that the same treatment suits all patients. For this reason, careful assessment of history, symptoms, and contributing factors is mandatory ( Box 1 ), as is a basic physical assessment including anal, abdominal, and rectal examination. Various investigations are commonly used, including manometry, electrophysiologic tests to assess reflexes and sensory function, and imaging of the sphincters using anal ultrasound or MRI. There is almost no evidence that the results of these tests change management or influence patient outcomes, however, and expert opinion suggests that evaluation of FI does not necessarily include manometry and imaging in the first instance for all patients. In the United Kingdom, national guidelines now encourage a step-wise approach to patients (in the absence of alarm symptoms, such as rectal bleeding or unexplained change in bowel habit, which warrant investigation in their own right), except those with acute sphincter rupture or complete rectal prolapse who should normally obtain imaging and a surgical opinion as first-line management. Other patients should normally have a targeted history and physical examination and then consideration of a range of conservative options, which can be combined according to individual need.

Onset of symptoms

Usual bowel habit

Changes in bowel habit

Stool consistency

Amount and frequency of FI

Urgency or urge FI

Passive soiling

Difficulty wiping clean after toilet

Nocturnal bowel symptoms

Abdominal pain and bloating

Evacuation difficulty

Straining

Incomplete evacuation

Pain

Digitation

Control of flatus

Rectal bleeding or mucus

Products used to manage FI

Diet: pattern and constituents

Fluid intake and types

Obstetric and surgical history

Comorbidities and physical abilities

Medications

Mental status

Abdominal, anal, perineal, and rectal examination

Elements of conservative care

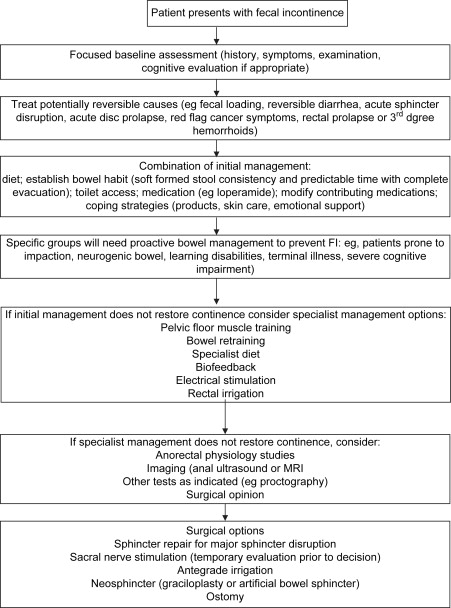

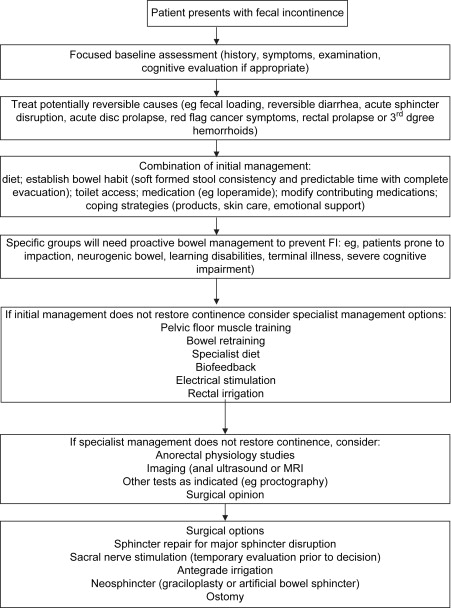

In the United Kingdom a step-wise approach has been recommended by the National Health Service ( Fig. 1 ). This includes identifying and addressing such factors as toilet access, diet, mobility, and cognitive factors. Medical management without any exercises or biofeedback has been found to improve symptoms in one third to one half of patients.

Patient Education and Understanding

Few patients understand how the gastrointestinal tract works and many have misconceptions, leading to counterproductive coping strategies. Patients often benefit from verbal and written information to enhance understanding of normal gut function and why their symptoms have arisen.

Bowel Habit

For most patients there should be an attempt to address bowel habit to enable the patient to achieve a complete evacuation of a formed stool at a predictable time each day. Even if FI persists, this makes the symptom much more tolerable and less limiting of activities. This might mean addressing constipation or evacuation difficulties for some patients (see the article by Rao, elsewhere in this issue), or reducing frequency and firming the stool for those with urgency and loose stool.

Diet Modification

There is an obvious relationship between dietary intake and defecation. Changing the amount, content, and timing of food and drink can make a major difference to bowel habit and stool consistency for some people, maybe particularly when there is an element of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) also present. Patients with FI secondary to loose stool have been found to respond to addition of soluble fiber to their diet. In one randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 39 patients, placebo was compared with two types of fiber supplement, both of which produced less FI than placebo, although another RCT has suggested that response to fiber is individual with some patients reporting benefit from either high- or low-fiber diets.

Other diet modification approaches should be individualized. Diarrhea-predominant IBS patients may benefit from fiber reduction, especially if intake is high to excessive. Lactose intolerance, undiagnosed celiac disease, and excess caffeine or alcohol intake may each contribute and be easily overlooked. Fructose intolerance affects up to one third of IBS patients and a diet with restricted fruit intake may improve symptoms.

Other Lifestyle Modifications

There are several other known risk factors for FI that have yet to be subjected to trials treating the symptom. Obesity, particularly morbid obesity, has been found to increase risk of FI, with rates over 60% reported, and such medications as Olestra to treat obesity have been reported to increase FI (probably by causing loose stool). It is not known if weight loss reverses symptoms once present. Depression is also found to coexist, but again treatment studies are lacking. Group therapy may be of benefit to some. Smoking can stimulate colonic motility and might in theory exacerbate urgency.

Urge Resistance Training

It is not difficult to imagine how patients with the socially devastating symptom of FI might become hypersensitive to any rectal or anal sensation and respond by an immediate search for toilet facilities. This seems to initiate a vicious circle of increasing urgency and anxiety for some patients, with urge FI resulting when the panic is overwhelming or no facilities can be located. Patients seem to lose all confidence in the ability to defer defecation and all rectal sensation is interpreted as an impending incontinence episode. This vicious circle can be broken in some patients by careful explanation and coaching to incrementally resist the urgency by repeatedly “holding on” for longer and longer time periods, possibly only a few seconds at first but gradually building to enough minutes to be confident that facilities can be reached. A similar program has been found successful in most patients with urge urinary incontinence whether secondary to detrusor instability or overactive bladder syndrome without instability. Although not yet formally evaluated as a single treatment for FI, such training has been incorporated in some biofeedback programs, where it may be combined with dietary or medication measures to firm the stool.

Medication

There is good evidence that loperamide (Imodium) can reduce frequency and firm the stool for people with FI related to loose stool. It has been found beneficial in patients with FI secondary to diarrhea-inducing medication, such as orlistat. Once constipation has been excluded as an underlying factor for FI, loperamide is often the first treatment option tried for FI. Patients do need careful teaching, however, on the mechanism of action and how to use loperamide. If used in doses recommended for frank diarrhea, constipation likely occurs. Because it dampens the gastrocolonic response, it is often best to take the medication approximately 30 to 60 minutes before a meal. Onset of action is rapid and a half-life of approximately 8 hours means that as-needed use (as opposed to routine dosage) can be useful. A syrup formulation enables fine titration of dose to individual response and gives the patient a useful sense of control.

Codeine phosphate, diphenoxylate, or low-dose amitriptyline (the latter particularly if there are symptoms of IBS) are alternatives, but tend to have more side effects than loperamide. Stool bulking agents may help to form loose stool. There is also a suggestion from a nonrandomized study that low-dose cholestyramine may be useful in patients with FI secondary to loose stool. The anorectum and pelvic floor have estrogen receptors and a small study has suggested benefit of postmenopausal hormone therapy for FI. Medications specifically to modify anal sphincter function have been reported but have yet to reach the market.

Pelvic Floor Muscle Training

In contrast to the large literature on urinary incontinence, there has been relatively little attention given to the option of exercises alone, without additional biofeedback for FI. The reason for this is unclear. The few studies that have been reported have given no pointers as to the optimum regimen of exercises (mode of teaching, number and type of exercises, or frequency of practice). Evidence is also lacking or conflicting as to efficacy. One RCT study found that exercises plus conservative management advice was no more effective than the advice alone; two studies have found digitally taught exercises as effective as biofeedback. Another small study has found equivalent outcomes comparing verbally taught exercises with biofeedback.

Because exercises are a relatively low-cost and possibly self-directed treatment, it may be worth trying before formal biofeedback training.

Elements of conservative care

In the United Kingdom a step-wise approach has been recommended by the National Health Service ( Fig. 1 ). This includes identifying and addressing such factors as toilet access, diet, mobility, and cognitive factors. Medical management without any exercises or biofeedback has been found to improve symptoms in one third to one half of patients.

Patient Education and Understanding

Few patients understand how the gastrointestinal tract works and many have misconceptions, leading to counterproductive coping strategies. Patients often benefit from verbal and written information to enhance understanding of normal gut function and why their symptoms have arisen.

Bowel Habit

For most patients there should be an attempt to address bowel habit to enable the patient to achieve a complete evacuation of a formed stool at a predictable time each day. Even if FI persists, this makes the symptom much more tolerable and less limiting of activities. This might mean addressing constipation or evacuation difficulties for some patients (see the article by Rao, elsewhere in this issue), or reducing frequency and firming the stool for those with urgency and loose stool.

Diet Modification

There is an obvious relationship between dietary intake and defecation. Changing the amount, content, and timing of food and drink can make a major difference to bowel habit and stool consistency for some people, maybe particularly when there is an element of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) also present. Patients with FI secondary to loose stool have been found to respond to addition of soluble fiber to their diet. In one randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 39 patients, placebo was compared with two types of fiber supplement, both of which produced less FI than placebo, although another RCT has suggested that response to fiber is individual with some patients reporting benefit from either high- or low-fiber diets.

Other diet modification approaches should be individualized. Diarrhea-predominant IBS patients may benefit from fiber reduction, especially if intake is high to excessive. Lactose intolerance, undiagnosed celiac disease, and excess caffeine or alcohol intake may each contribute and be easily overlooked. Fructose intolerance affects up to one third of IBS patients and a diet with restricted fruit intake may improve symptoms.

Other Lifestyle Modifications

There are several other known risk factors for FI that have yet to be subjected to trials treating the symptom. Obesity, particularly morbid obesity, has been found to increase risk of FI, with rates over 60% reported, and such medications as Olestra to treat obesity have been reported to increase FI (probably by causing loose stool). It is not known if weight loss reverses symptoms once present. Depression is also found to coexist, but again treatment studies are lacking. Group therapy may be of benefit to some. Smoking can stimulate colonic motility and might in theory exacerbate urgency.

Urge Resistance Training

It is not difficult to imagine how patients with the socially devastating symptom of FI might become hypersensitive to any rectal or anal sensation and respond by an immediate search for toilet facilities. This seems to initiate a vicious circle of increasing urgency and anxiety for some patients, with urge FI resulting when the panic is overwhelming or no facilities can be located. Patients seem to lose all confidence in the ability to defer defecation and all rectal sensation is interpreted as an impending incontinence episode. This vicious circle can be broken in some patients by careful explanation and coaching to incrementally resist the urgency by repeatedly “holding on” for longer and longer time periods, possibly only a few seconds at first but gradually building to enough minutes to be confident that facilities can be reached. A similar program has been found successful in most patients with urge urinary incontinence whether secondary to detrusor instability or overactive bladder syndrome without instability. Although not yet formally evaluated as a single treatment for FI, such training has been incorporated in some biofeedback programs, where it may be combined with dietary or medication measures to firm the stool.

Medication

There is good evidence that loperamide (Imodium) can reduce frequency and firm the stool for people with FI related to loose stool. It has been found beneficial in patients with FI secondary to diarrhea-inducing medication, such as orlistat. Once constipation has been excluded as an underlying factor for FI, loperamide is often the first treatment option tried for FI. Patients do need careful teaching, however, on the mechanism of action and how to use loperamide. If used in doses recommended for frank diarrhea, constipation likely occurs. Because it dampens the gastrocolonic response, it is often best to take the medication approximately 30 to 60 minutes before a meal. Onset of action is rapid and a half-life of approximately 8 hours means that as-needed use (as opposed to routine dosage) can be useful. A syrup formulation enables fine titration of dose to individual response and gives the patient a useful sense of control.

Codeine phosphate, diphenoxylate, or low-dose amitriptyline (the latter particularly if there are symptoms of IBS) are alternatives, but tend to have more side effects than loperamide. Stool bulking agents may help to form loose stool. There is also a suggestion from a nonrandomized study that low-dose cholestyramine may be useful in patients with FI secondary to loose stool. The anorectum and pelvic floor have estrogen receptors and a small study has suggested benefit of postmenopausal hormone therapy for FI. Medications specifically to modify anal sphincter function have been reported but have yet to reach the market.

Pelvic Floor Muscle Training

In contrast to the large literature on urinary incontinence, there has been relatively little attention given to the option of exercises alone, without additional biofeedback for FI. The reason for this is unclear. The few studies that have been reported have given no pointers as to the optimum regimen of exercises (mode of teaching, number and type of exercises, or frequency of practice). Evidence is also lacking or conflicting as to efficacy. One RCT study found that exercises plus conservative management advice was no more effective than the advice alone; two studies have found digitally taught exercises as effective as biofeedback. Another small study has found equivalent outcomes comparing verbally taught exercises with biofeedback.

Because exercises are a relatively low-cost and possibly self-directed treatment, it may be worth trying before formal biofeedback training.

Biofeedback for fecal incontinence

For many years case series and expert opinion proposed “biofeedback” as the treatment option of first choice in the treatment of FI. Case series almost unanimously reported positive patient outcomes, often in over 70% of patients. Case series methodology, however, has widely acknowledged weaknesses (it was difficult to know if the biofeedback was the crucial element in an often complex package of care including many of the measures outlined previously). In addition, outcome measurements were often poor, or proxy measures, such as anal sphincter pressures.

Different methods of biofeedback

There is no standard method of biofeedback for FI and some authors have failed to describe the makeup of their intervention. Most include one-to-one sessions with a therapist (doctor, nurse, physical therapist, clinical scientist, or other) of different durations (typically 30–60 minutes) at variable time intervals (from more than once daily to once per month or less frequently) and some have admitted patients to hospital for intensive treatment. All involve some type of anorectal instrumentation to enable the patient to become aware of voluntary or autonomic functions and modify those functions, but the proportion of each session devoted to this activity is seldom stated, because presumably most therapists also interact socially and review symptoms and incorporate other advice and education. The impression is that some authors have used sessions for multiple repeated attempts to modify function, whereas others have used instruments as a quick check on progress and spent most of each session concentrating on the education elements. The main modalities of instrumented biofeedback are discussed next.

Measures of Voluntary Squeeze

This has been displayed to the patient using electromyography (EMG), manometry, and anal or perineal ultrasound. The patient may lie or sit with direct views of the computer or imaging monitor and attempt squeezing with real-time feedback (usually visual but occasional auditory) of the success of each attempt. The therapist can coach the patient to improve performance. Some equipment sets goals for patients, such as grid lines to follow for the pressure of each squeeze. The aim is usually to demonstrate the correct action to the patient and then to monitor progress of a structured pelvic floor muscle exercise program conducted by the patient at home between visits. Some authors have included abdominal EMG to enable the patient to isolate anal contraction from abdominal effort, avoiding any counterproductive straining effect during exercises.

Modification of Anorectal Sensation

Typically, a rectal balloon is inserted and gradually filled with air or water. Depending on the assessed problem, this may be used to raise or lower sensory thresholds or tolerated volumes. Patients found to have a high threshold of sensation to rectal filling have been reported to experience improved symptoms if their threshold can be lowered, presumably by allowing earlier perception of stool and the possibility of responding by anal contraction or finding toilet facilities promptly. This is usually achieved by finding the volume that can be reliably detected and then repeatedly filling at volumes below this threshold until the patient learns to perceive this. Conversely, patients with an oversensitive rectum may learn that if this sensation is ignored or resisted, then it diminishes and larger volumes can be tolerated.

Co-ordination Training

A two- or three-balloon system is used to simulate the rectoanal inhibitory reflex and train the patient to increase speed of reaction and voluntary squeeze increment in response. The rectal balloon is inflated with air or water. One or two balloons in the anal canal record the consequent fall in anal pressure and the patient is asked to counteract this fall by a voluntary contraction of the external anal sphincter. Repeated trials may be conducted until the patient is successful in achieving no fall in anal pressure. Alternatively, the patient is taught to squeeze in response to successively weaker rectal stimuli. The patient may also be instructed to practice the same maneuver in response to each urge to defecate. This “urge resistance” has also been described as an instruction to the patient in the absence of any biofeedback to assist in learning the technique.

Biofeedback protocols have varied greatly in terms of number and frequency of sessions, length of sessions, and therapist training. It has been reported in a nonrandomized study that less intensive telephone follow-up may be as effective as face-to-face contact, suggesting that the instrumental elements of biofeedback may not be the most crucial element.

Evidence for the Efficacy of Biofeedback

Given the possible complexity of an individual patient care plan during biofeedback (which might include any or all of the modalities of biofeedback and adjunctive therapies listed previously), it has been difficult to determine whether biofeedback per se is the effective element of any intervention. Trials comparing different methods of biofeedback, including home practice machines, EMG, pressure, and ultrasound biofeedback, have failed to find any difference in outcomes. The addition of biofeedback and exercises after sphincter repair made little difference compared with sphincter repair alone. A Cochrane review of 11 RCTs has concluded that there is no evidence at present of one method of biofeedback giving any benefit over any other method, or that exercises or biofeedback offer any advantage over other conservative care. The evidence from RCTs to 2008 is summarized in Table 2 .