Cystic Transformation of the Rete Testis (Synonym: Also Called Giant Cystic Degeneration of the Rete Testis)

Nistal et al.

138 studied 1,798 autopsy and 518 surgical specimens from the testis and epididymis, and identified cystic transformation of the rete testis in 20 autopsy and 18 surgical pathology specimens.

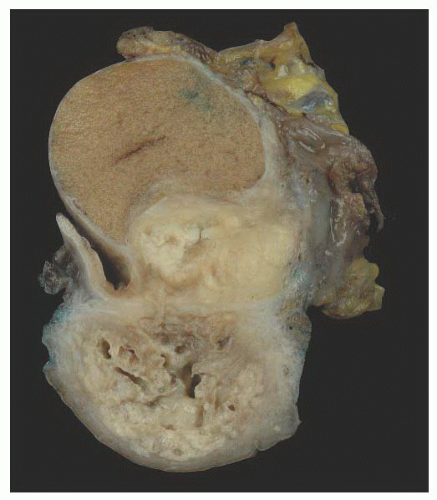

138 The cystic transformation was thought to be due to several different etiologies. One cause of this lesion is mechanical compression of the extratesticular excretory ducts, resulting from neoplasia or other masses such as hematoceles. Cystic transformation may also follow postvasectomy inflammation or it may be related to infection such as epididymitis. An ischemic etiology has also been proposed in elderly men who have atherosclerosis in the epididymal branch of the testicular artery with associated atrophy of the head of the epididymis. Hormonal abnormalities may cause cystic transformation of the rete testis in patients with cirrhosis; these patients have increased peripheral conversion of androgen to estrogen and develop bilateral epididymal atrophy and columnar transformation of the rete testis epithelium. One case of giant cystic degeneration of the rete testis has been reported recently in an elderly adult man treated with LHRH for prostate adenocarcinoma.

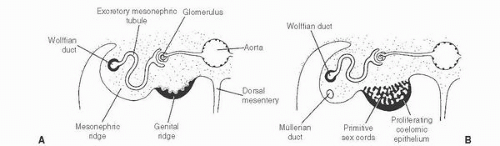

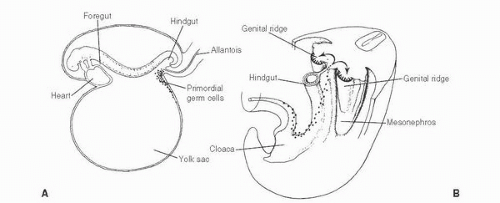

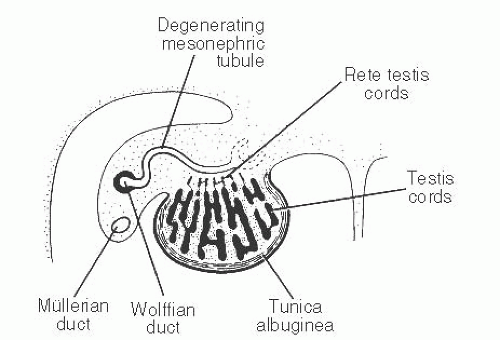

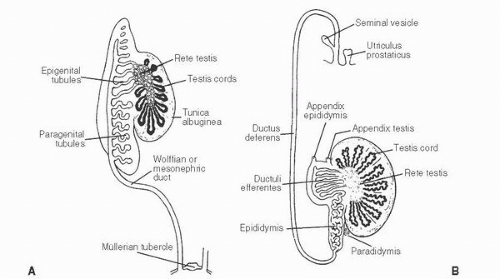

139 The patient age, the postulated effect to antiandrogen therapy, and the 10-cm size of the lesion are all unusual for this lesion. Malformations, such as cryptorchidism, that have dissociation between the rete testis (derived from the sex cords) and the epididymis (derived from the mesonephric duct) may also result in cystic transformation of the rete testis (

Box 13-2).

Mesothelial Cysts

Mesothelial-lined cysts of the paratesticular area are rare and may involve the tunica albuginea, tunica vaginalis, epididymis, or spermatic cord.

18,

141,

142,

143,

144 They usually occur in men over 40 years of age. They may either be asymptomatic or patients may present with a painful mass simulating testicular tumors. These cysts may be single or multiple, but they are usually unilateral and located on the anterolateral surface of the testis.

144 They measure from 0.3 to 0.4 cm in diameter and contain serous or blood-tinged fluid. The cysts are lined by single-layered, non-atypical, flattened, or cuboidal mesothelial cells. The epithelium is surrounded by hyalinized connective tissue. Squamous metaplasia may be present. The cysts are surrounded by fibrous tissue. They are benign lesions that should be treated conservatively.

Cysts of the Epididymis

Small benign cysts of the epididymis are common. They measure 1 to 2 cm in diameter. Pain and torsion may occur with larger cysts.

145 Polycystic kidney disease has been associated with multiple epididymal cysts.

146 Bilateral epididymal cysts have been described in a patient with von Hippel-Lindau disease and early-onset renal cell carcinoma.

147 Epididymal cysts have also been reported in 10% of men exposed to DES in utero

148 (

Box 13-2).

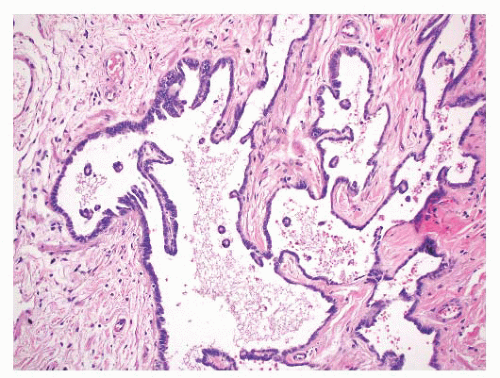

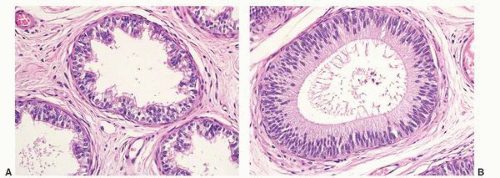

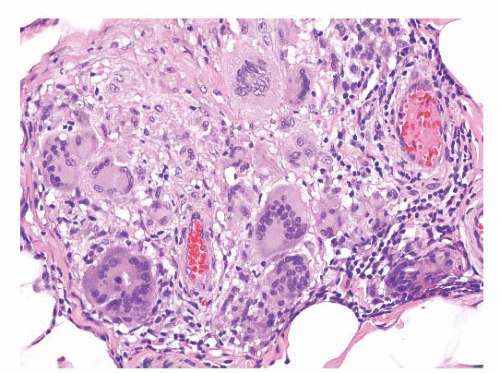

Epididymal cysts usually occur in the head of the epididymis. They are thought to arise from efferent ductules.

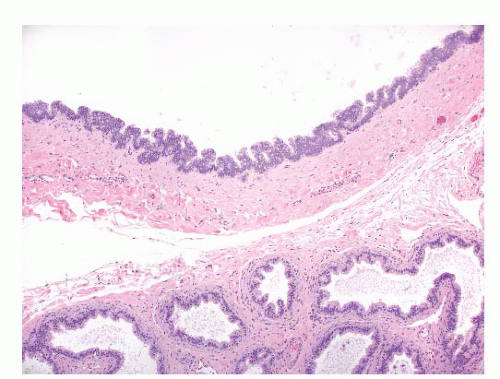

21 They may be unilocular or multilocular, and they are lined by a single layer of flat to cuboidal epithelial cells that may display variable numbers of cilia (

Fig. 13-12). Cytologic atypia is not a feature of epididymal cysts. If spermatozoa are present in the cysts, the lesions are called spermatoceles. Small papillary structures containing connective tissue cores lined by a single layer of bland epithelium may protrude into the cysts.

149

Spermatocele

Spermatoceles result from cystic dilation of the efferent ductules, the tubules of the rete testis, or the aberrant ducts. Cysts may become large, with thin walls. Cloudy fluid present in spermatoceles is a result of sperm present in the cystic spaces. The fibromuscular walls are lined by cuboidal to columnar, sometimes ciliated, epithelium. The epithelial lining of long-standing spermatocele may be quite attenuated and may resemble a mesothelial or simple squamous layer.

18 Sometimes they contain papillary proliferations lined by benign epithelial cells.

149 Calcification may occur.

150 Clusters of small blue cells have been reported in spermatocele and hydrocele specimens. They may represent sloughed rete testis epithelium and they may mimic the appearance of small cell carcinoma.

151 Bland nuclei, lack of mitotic figures, and lack of staining with neuroendocrine markers are features indicative of benign epithelium.

Dermoid and Epidermoid Cysts

Epidermoid cysts are rare in the paratestis.

152 They present either incidentally during hernia repair procedures or as painless enlarging masses located in the spermatic cord. They are lined by keratinizing squamous epithelium and contain intracystic keratinous debris. Dermoid cysts have also been reported in the spermatic cord.

153,

154 They contain skin appendage structures in addition to squamous epithelium.

Most epidermoid and dermoid cysts are considered benign neoplasms, in contrast to teratomas. Some epidermoid cysts may represent a metaplastic process derived from mesothelium. The possibility of extension or metastasis from a tumor in the testis should be excluded before making this diagnosis.

Hydrocele (Acquired)

A hydrocele is a fluid accumulation between the visceral and parietal layers of the tunica vaginalis. Congenital hydroceles have been discussed above (congenital abnormalities). Acquired hydroceles may be idiopathic or secondary to infections or neoplasms (

Box 13-2). They represent the most common cause of painless scrotal swelling. They form over time, and neoplasm should be excluded in the case of a rapid formation of a hydrocele. Hydroceles usually transilluminate, except in cases where the tunica vaginalis is thickened. Ultrasound shows an anechoic fluid collection. The pathogenesis of acquired hydroceles reflects an imbalance between fluid secretion and resorption in the tunica vaginalis.

155 Defective lymphatic drainage has been suggested as a cause of hydroceles.

156Chronic hydroceles may become inflamed, with a proliferation of fibrous tissue. The testis may become adherent to the parietal tunica vaginalis. These features may mimic neoplasms clinically.

34,

62,

63 The resulting mass-like lesions may be more than twice the normal size of the normal testis, but they are diffuse and symmetrical.

34 Patients in one series of nine patients ranged from 22 to 88 years of age.

63 Most patients had hydroceles that were excised because of the clinical similarity to neoplasms.

63 Microscopic examination showed features typical of a reactive process, including mesothelial hyperplasia with fibrosis and some chronic inflammation.

63 Organizing hemorrhage in a hydrocele may also simulate a neoplasm until it is examined microscopically.

Hematocele

Hematoceles represent collections of blood in the tunica vaginalis. They may be acute or chronic, and they may have a mass effect. Causes include trauma, torsion, tumor, and surgery (

Box 13-2). Varicoceles may be present, and minor trauma may cause rupture of one of the dilated blood vessels.

69 Patients present with a mass and scrotal pain. Most hematoceles resolve spontaneously with conservative therapy, but some may become fibrotic and calcified.

157

Rosai-Dorfman Disease

A few cases of Rosai-Dorfman disease (sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy) have been described in the epididymis.

160 Patients may be either children or adults, and lymph nodes are also often involved.

5 This process may result in nodules, or it may diffusely involve the epididymis. Microscopic examination shows sheets of histiocytes that contain oval nuclei and abundant pale cytoplasm with poorly defined cell borders. The histiocytes may contain phagocytosed lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and erythrocytes.

Calcification, Bone, and Cartilage

An autopsy study of testes and associated rete testes showed a rare lesion called “nodular proliferation of calcifying connective tissue in the rete testis”

161 in three men with histories of myocardial infarction. Polypoid projections in the rete spaces had connective tissue cores with calcification and were covered by benign, flattened epithelial cells.

Calcification may cause firm nodules in the epididymis, usually associated with sperm granuloma, filarial infection, or tuberculosis.

162 Calcification of the epididymis may also be seen in patients on hemodialysis.

163 Two cases of heterotopic bone trabeculae in the epididymis have been reported.

18,

164 Cartilage has also been seen in the epididymis of infants.

165Calcification of the seminal vesicles and vasa deferentia may indicate systemic disease.

166 This lesion may be associated with diabetes, uremia with secondary hyperparathyroidism, prostatitis, infections (tuberculosis, schistosomiasis, gonorrhoea), and congenital abnormalities. Bilateral calcification of the vas deferens has been reported in a hemodialysis patient

167 and, rarely, the condition is idiopathic.

Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor (Synonyms: Also Called Inflammatory Pseudotumor, Pseudosarcomatous Myofibroblastic Proliferation, and Proliferative Funiculitis)

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor and related lesions in the paratestis occur most often in the spermatic cord,

62,

170,

171,

172,

173,

174,

175,

176 but isolated cases have also been reported in the rete testis

and epididymis.

171,

172 They may present as mass lesions, or they may be incidental findings in inguinal hernia specimens. Some of these lesions in the epididymis may be a reaction to torsion and chronic ischemia.

170,

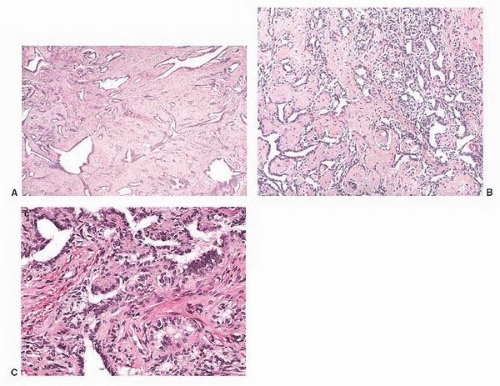

176These lesions are usually gray or tan, firm nodules that are <3 cm in size, although an occasional lesion has measured 7 cm.

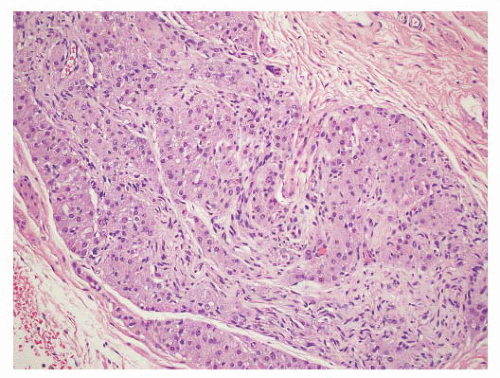

5 Some are well circumscribed (

Fig. 13-13), but many are poorly demarcated. Areas of hemorrhage or cystic change may occur rarely. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors are composed of tapering spindle to stellate-shaped cells with vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm. The stroma is fibrous or myxoid. Cellularity varies in different parts of the lesions and may be greater in the central portion of the lesion. Inflammatory and giant cells may cause the lesion to resemble fasciitis seen elsewhere in the body.

5 Hyalinized fibrous tissue characteristically surrounds blood vessels. The mitotic rate is usually low, although torsion has been associated with greater numbers of mitotic figures.

176 Atypical mitotic figures are not present. It is possible that these lesions may progress to the densely collagenous and hyalinized “fibrous pseudotumors.”

5 Immunohistochemical stains performed on inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors show cells will be of myofibroblastic phenotype; stains may be positive for actins, vimentin, desmin, and sometimes keratin,

34 although these stains are not usually necessary for diagnosis of this lesion.

The differential diagnosis of inflammatory pseudotumors includes rhabdomyosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, sclerosing liposarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, and spindle cell mesothelioma. The bland cytologic features, low mitotic rate, lack of atypical mitoses, and overall resemblance to fasciitis are features that are helpful in recognizing the reactive nature of this lesion and distinguishing it from malignant neoplasms.

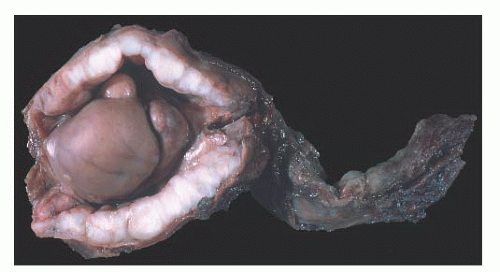

Fibrous Pseudotumor (Synonyms: Called Fibromatous Periorchitis, Nodular Periorchitis Additional Synonyms: Chronic Periorchitis, Proliferative Funiculitis, Fibrous Proliferation of Tunics, Fibroma, Nonspecific Testicular Fibrosis, Nodular Fibrous Periorchitis, Nodular Fibrous Pseudotumor, Inflammatory Pseudotumor, Reactive Periorchitis, Pseudofibromatous Periorchitis)

Paratesticular fibrous pseudotumors present as mass lesions. They are most often seen in the third decade of life,

177,

178 but one case has been reported in a 5-year-old boy.

179 One patient had retroperitoneal fibrosis, one had Gorlin syndrome,

180 and one lesion was associated with testicular infarction.

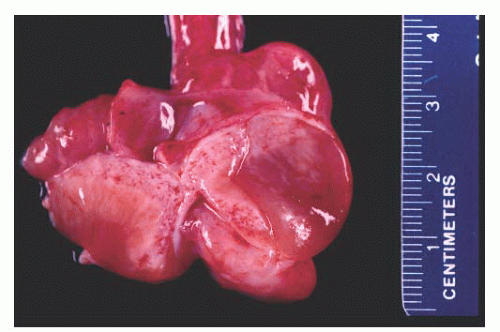

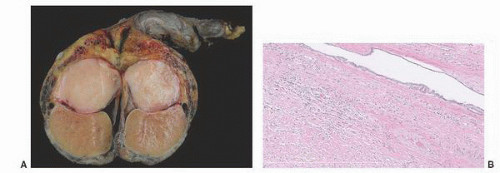

181 After adenomatoid tumors, these lesions represent the most common cause of masses in the paratestis. Patients have single or multiple nodules or plaques in the tunica vaginalis,

182,

183 epididymis,

184,

185 or spermatic cord, and the nodules range from 0.5 to

8 cm

177 (

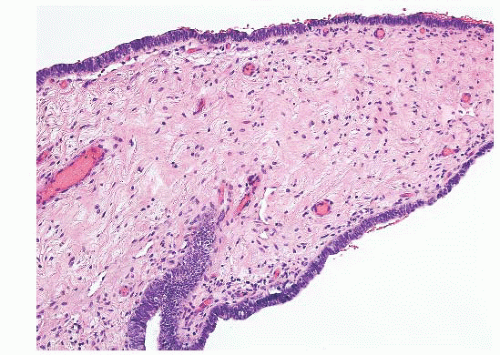

Fig. 13-14). In a diffuse form, dense fibrous tissue involves the tunica vaginalis.

Microscopically, this lesion is characterized by dense, hyalinized, fibrous tissue often containing lymphocytes and plasma cells with occasional germinal centers.

186 Calcification and ossification may occur.

187 Three histologic types of fibrous pseudotumor have been recently described,

188 although this subclassification is mainly of academic interest. Plaque-like lesions have dense fibrous stroma without significant inflammation, inflammatory sclerotic pseudotumors contain dense fibrous tissue with significant inflammation and myofibroblastic lesions have reactive appearing cells with numerous capillaries and sparse chronic inflammation.

188 Paratesticular fibrous pseudotumor does not display significant nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, or necrosis. The differential diagnosis of paratesticular fibrous pseudotumor includes solitary fibrous tumor, leiomyoma, fibromatosis, spindle cell mesothelioma, and neurofibroma.

188Immunohistochemical stains performed on paratesticular fibrous pseudotumors display positive staining for smooth muscle actin in more than 80% of cases.

188 Surprisingly, stains for cytokeratin, calretinin, and CD34 are positive in about half of the cases.

188 All cases in a recent study were negative for B-catenin and ALK-1, and these lesions have a very low proliferation index as measured by Ki-67 staining.

188Potential cells of origin include myofibroblasts and submesothelial stromal cells, but paratesticular fibrous pseudotumors may be a nonspecific pattern resulting from a variety of pathogenetic processes.

188 Past histories of trauma, surgery, infection, and inflamed hydroceles in some patients suggest a reactive etiology,

63,

189 although some patients have no such prior events. Some fibrous pseudotumors are thought to represent an advanced stage of inflammatory pseudotumors.

149,

177,

190 Paratesticular fibrous pseudotumors are benign lesions, and local excision is curative.

“Tumor” of the Adrenogenital Syndrome and Related Lesions

This lesion develops in the paratesticular region of men with the adrenogenital syndrome who are not adequately treated, especially men with the salt-losing form of the syndrome. Nodules of steroid-type cells may occur in the epididymis, the spermatic cord, or the tunica albuginea.

38,

191,

192,

193 The paratesticular lesions may either extend from testicular nodules or be separate dark brown nodules measuring up to 1.5 cm in diameter.

38 Sometimes, fibrous septa are present in the nodules. The microscopic appearance of these lesions is quite characteristic. Paratesticular nodules of steroid type cells are present. Bands of fibrous tissue and focal nuclear atypia are also seen.

Five cases of rete testis-associated nodular steroid cell nests associated with the rete testis have recently been reported.

194 They are discrete conspicuous, unencapsulated nodules with vascular sinusoids between nests or cords of cells. They display strong melan A immunostaining, absent-to-weak inhibin staining and absent-to-moderate calretinin expression, in contrast to interstitial Leydig cells and testicular adnexal Leydig cells (TTAGS). The cells in rete testis-associated nodular steroid nests have been postulated to represent the precursor of testicular tumors of the adrenogenital syndrome.

194Patients with Nelson syndrome have ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas following bilateral adrenalectomy for Cushing syndrome. These patients may also develop paratesticular steroid cell nodules.

39,

195,

196 All reported cases have been bilateral, with nodules ranging up to 5.5 cm in diameter.

195,

196 They may produce cortisol and result in recurrence of Cushing syndrome. Gross and microscopic features are similar to those seen in patients with the adrenogenital syndrome. Bilateral small steroid cell nodules have also been described in children with Cushing syndrome and nodular hyperplasia of the adrenal cortex.

38,

197 They also have the same morphologic characteristics as the nodules associated with the adrenogenital syndrome.

Some masses of paratesticular steroid cells may also develop by stimulation of ectopic adrenocortical tissue found in about 10% of infants and some older patients.

5,

34,

35,

198,

199