Chapter 24 Papillectomy and Ampullectomy

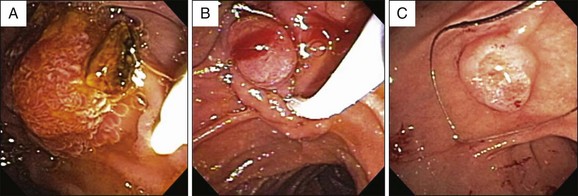

Ampullary neoplasms are rare, with a reported prevalence of 0.04% to 0.12% in autopsy series.1,2 Endoscopically the ampulla can appear enlarged and abnormal due to various tumors (benign and malignant) as well as other etiologies such as papillitis, gastric foveolar metaplasia, or pancreatic acinar hyperplasia (Fig. 24.1). Ampullary tumors can be classified based on their layer of origin: arising from the epithelium (e.g., adenomas, adenocarcinomas, lymphomas) and arising from the subepithelium (e.g., neuroendocrine tumors, lipomas, leiomyomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, lymphangiomas, fibromas, and hamartomas). Adenomatous ampullary lesions are by far the most common of these, and although uncommon in the general population, they are increased two- to threefold in genetic polyposis syndromes, especially familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and its variants.3 Between 40% and 100% of FAP patients will also develop duodenal adenomas, which are frequently numerous and also have malignant potential. Ampullary adenomas can arise from the surface epithelium or the inner lining of the ampulla.4

Historically, ampullary adenomas presented late with a high incidence of underlying malignancy. Endoscopic management in the early years consisted mainly of palliation of obstructive jaundice with biliary sphincterotomy and stent placement. Patients often become symptomatic when the lesions are large enough to cause obstruction, presenting with cholestasis, cholangitis, pancreatitis, nonspecific abdominal pain, and, less commonly, bleeding.5,6 With increased awareness among endoscopists and the increasing use of cross-sectional imaging (computed tomography [CT] and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), these lesions are being recognized at earlier stages with a lower incidence of underlying malignancy. Asymptomatic lesions are being recognized more commonly in patients undergoing endoscopy for unrelated reasons such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), surveillance of Barrett esophagus, and dyspepsia or, alternatively, in patients undergoing surveillance in FAP.7,8

Treatment Options

Once diagnosed with a biopsy-proven ampullary adenoma, patients have four options: close endoscopic surveillance with or without biliary stent placement (for cholestasis or biliary dilation), endoscopic papillectomy, surgical ampullectomy and local resection, or pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple operation). There are no clinical trials comparing one approach to another. The decision regarding treatment choice is influenced by various factors, including patient preference, associated comorbidities that may affect fitness for surgery, local endoscopic and surgical expertise, the lesion’s characteristics, and whether sporadic or in the setting of FAP. For patients with large lesions (greater than 4 to 5 cm), presence of high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma in situ, or obvious nodal disease on cross-sectional imaging or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), pancreaticoduodenectomy should be considered.9–11

Although associated with the highest cure rates and lowest recurrence rates, pancreaticoduodenectomy comes with the price of a high morbidity of 25% to 63% with a mortality ranging from 0% to 13% (higher rates are reported in patients with malignant disease).12,13 Surgical local resection is generally associated with lower morbidity (14% to 27%) and mortality (0% to 4%), but recurrence rates can be as high as 17% to 32%, thus necessitating continued postoperative endoscopic surveillance.14,15 As colonoscopic polypectomy has become routine for even large colonic polyps, and with the acceptable morbidity, mortality, and recurrence rates of surgical local resection for papillary adenomas, endoscopic papillectomy emerged as an acceptable alternative to surgery.

Endoscopic papillectomy was first described by Suzuki et al. in 1983,16 and the first large case series was reported by Binmoeller et al. in 1993.9 Over the last 2 decades, many more studies have been published showing high success rates, low morbidity, and minimal mortality. Endoscopic papillectomy has therefore gained increasing acceptance as the treatment of choice for the vast majority of patients with ampullary adenomas.

Considerations in FAP

The management of ampullary adenomas in the setting of FAP is further complicated by the fact that complete excision does not eliminate the risk of recurrence or new upper gastrointestinal tract cancers. Fortunately, the risk of histologic progression of upper gastrointestinal tract adenomas in FAP patients appears to be low.17,18 In one of the largest studies on surveillance of duodenal and ampullary adenomas in 114 patients with FAP, there was progression in size in 26%, progression in number in 32%, and histologic progression in 11% with only one patient developing a periampullary cancer.18 This has prompted some experts to propose surveillance endoscopy with biopsies only, rather than excision, for FAP patients with ampullary adenomas in the absence of rapid growth or high-grade dysplasia on endoscopic biopsy. The obvious benefit of this approach is avoidance of the risks associated with excision of these lesions. The limitation of endoscopic surveillance with biopsies alone is the potential to miss occult foci of high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma. In a study of 33 patients with ampullary adenomas (not necessarily FAP) in whom endoscopic biopsies were obtained, carcinoma was found at final surgical pathology in 5 of 10 patients with high-grade dysplasia and in 3 of 19 patients with low-grade dysplasia.19 Because of these competing issues, the management of ampullary adenomas in FAP patients is determined on a case-by-case basis, taking into consideration all of the aforementioned factors in addition to the patient’s wishes and risk tolerance.

Technique (Box 24.1)

The role of endoscopic papillectomy was reviewed in a guideline statement published by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in 2006.20

Box 24.1

Summary of the Technique

Staging of ampullary adenomas with cross-sectional imaging (CT or MRI) is not routine although in the setting of significant weight loss and dilated ducts should be done to evaluate for the presence of nodal and metastatic disease.8

Staging of ampullary adenomas with cross-sectional imaging (CT or MRI) is not routine although in the setting of significant weight loss and dilated ducts should be done to evaluate for the presence of nodal and metastatic disease.8

Endoscopic ultrasound is very helpful in defining lesion size, depth of invasion, ductal involvement, and anatomy but is not routine, especially in small lesions and in the absence of jaundice, history of acute pancreatitis, or dilation of the pancreatic or bile ducts.

Endoscopic ultrasound is very helpful in defining lesion size, depth of invasion, ductal involvement, and anatomy but is not routine, especially in small lesions and in the absence of jaundice, history of acute pancreatitis, or dilation of the pancreatic or bile ducts.

ERCP prior to papillectomy is indicated in all patients to assess whether intraductal involvement is present and to identify pancreatic ductal anatomy for conditions such as pancreas divisum.

ERCP prior to papillectomy is indicated in all patients to assess whether intraductal involvement is present and to identify pancreatic ductal anatomy for conditions such as pancreas divisum.

A duodenoscope is used to perform the papillectomy in a similar manner to colonoscopic snare polypectomy, usually using blended current.

A duodenoscope is used to perform the papillectomy in a similar manner to colonoscopic snare polypectomy, usually using blended current.

Thermal ablation may be used in select cases as adjunctive therapy.

Thermal ablation may be used in select cases as adjunctive therapy.

Prophylactic pancreatic sphincterotomy and stent placement should be attempted in all patients.

Prophylactic pancreatic sphincterotomy and stent placement should be attempted in all patients.

Routine biliary sphincterotomy is recommended, although biliary stent placement is not routine in the presence of good biliary drainage.

Routine biliary sphincterotomy is recommended, although biliary stent placement is not routine in the presence of good biliary drainage.

Surveillance is critical after complete resection due to known local recurrences.

Surveillance is critical after complete resection due to known local recurrences.

Initial Endoscopic Assessment

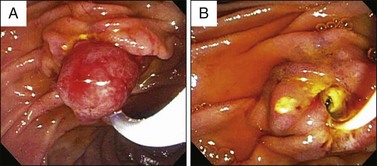

1 Conventional Endoscopy

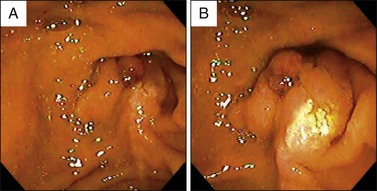

Visualization of the ampulla is possible with a conventional forward-viewing endoscope but is best performed with a duodenoscope. A large periampullary diverticulum can hinder endoscopic visualization (Fig. 24.2). Ampullary adenomas can have varied appearances, ranging from appearing normal in the setting of FAP, to a slight enlargement, to flat laterally spreading, to granular or polypoid, with or without ulceration (Fig. 24.3). Although some endoscopic features alone should raise the suspicion for an associated underlying malignancy (large, friable, ulcerated, indurated lesions), endoscopic biopsies are needed to confirm the pathology. Endoscopic biopsies are, however, notoriously suboptimal at detecting underlying malignant foci. The reported rates of malignancy in ampullary adenomas is approximately 20% to 30%.8,12,21 Detection rates for cancer present within adenomas based on biopsy alone range from a dismal 40% to 89%.14,15,22–26 These arguments may suggest favoring a radical surgical approach in all patients; however, this is mostly based on data obtained from surgical patients. Nowadays, many ampullary lesions are diagnosed at routine endoscopy, with a much higher percentage being detected at earlier stages. In the more recent and larger endoscopic series (over 100 patients in each), incidental or asymptomatic presentation of ampullary adenomatous lesions was seen in 25% to 33%.2,8,27 Rates of malignancy in papillectomy specimens ranged from 6% to 8%.2,8,27 In addition, there are clinical, endoscopic, and imaging features that should give pause prior to endoscopic papillectomy even if biopsies alone do not reveal cancer; these are clinical features such as significant weight loss and jaundice and endoscopic features such as large (>4 cm), friable, ulcerated, fixed lesions and evidence of dilated ducts especially with intraductal extension. In our series of 102 patients who underwent papillectomy, 8 (7%) were found to have invasive cancer. Of these eight patients, two were referred by surgeons because of significant comorbidities precluding pancreaticoduodenectomy. Thus only 6 of 102 (5%) patients who appeared endoscopically resectable and who underwent papillectomy had invasive cancer on final pathology.8 Therefore, although it is true that biopsy alone has a definable miss rate in diagnosing invasive cancer, only a minority of patients with invasive cancer seem to have endoscopically resectable lesions. Most authors propose that EUS in selected patients could help decrease this unnecessary papillectomy rate even further, with many centers performing EUS routinely for all ampullary adenomas.28,29

2 Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) and Intraductal Endoscopic Ultrasound (IDUS)

Some authors recommend performing EUS in all patients with ampullary adenomas whereas others recommend EUS only for selected cases.8,28,29 As mentioned above, clinical features of weight loss and jaundice, cross-sectional imaging features of dilated ducts, and endoscopic appearances of lesions (friable, ulcerated, indurated, and, in our practice, lesions >2 cm) should prompt an EUS prior to papillectomy. EUS is very useful in evaluating tumor size, depth of invasion of the duodenal wall, involvement of the biliary or pancreatic ducts, and periampullary lymph nodes (Fig. 24.4).20,29–32 Radial scanning echoendoscopes are used more commonly than linear echoendoscopes. The T-staging accuracy of EUS is very good (83% to 90%) and superior to CT and MRI.29,33–36 N-staging accuracy in some studies is reported to be better than CT (84% versus 68%)32 while in others it is reported to be comparable to CT and MRI (68% versus 59% versus 77%).37 Prior sphincterotomy and the presence of a biliary or pancreatic stent, however, can decrease EUS T-stage accuracy.

The optimal management of patients with intramucosal cancer (pT1) remains debatable. In these patients, lymphatic, vascular invasion, and lymph node metastases do not occur.38,39 Local resection can be justified if biliary or pancreatic ductal infiltration can be excluded. The evaluation of tumor invasion of the sphincter of Oddi remains challenging. Intraductal endoscopic ultrasound (IDUS) can be performed in a transpapillary or percutaneous fashion. IDUS has a good resolution because of the use of high-frequency ultrasound (20 to 30 MHz) compared with EUS (7.5 to 10 MHz). There are three studies comparing EUS with IDUS in ampullary cancer. Itoh et al.29 reported the diagnostic accuracy of IDUS and EUS in 32 patients with ampullary cancer who underwent surgical resection. The TNM staging accuracy of IDUS was comparable to EUS (88% versus 90%) but the depiction of the sphincter of Oddi and detailed staging was better with IDUS. Menzel et al.40 reported the results of a prospective study on 27 patients with ampullary neoplasm (adenoma in 12, adenocarcinoma in 15) who underwent surgical management. They concluded that IDUS was significantly superior to EUS with regard to tumor visualization and staging (staging accuracy 93% versus 62%). Ito et al.30 performed EUS and transpapillary IDUS in 40 patients (adenocarcinoma in 33, adenoma in 7). IDUS had a slightly better T-stage accuracy (78% versus 62%) but was no better at detecting ductal involvement (90% versus 88%). Due to the paucity of data and similar performance of IDUS and EUS, IDUS cannot be routinely recommended at this time. However, as probe technology improves it may become more commonly used to differentiate more subtle, early invasive cancers of the ampulla, thus precluding unnecessary papillectomies.

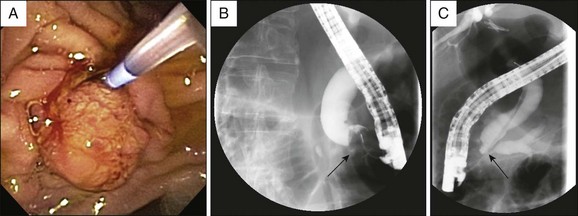

3 Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

While EUS is generally performed prior to resection to improve staging accuracy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is performed at the time of papillectomy to exclude intraductal tumor involvement and to perform pancreaticobiliary sphincterotomies and stent placement. If EUS is unavailable or if the findings at EUS are equivocal, performance of ERCP is critical prior to resection (Fig. 24.5). Surgical referral should be considered if there is evidence of intraductal involvement, especially if there is extension >1 cm into the bile or pancreatic ducts. Cholangiopancreatography outlines the ductal anatomy to help access the pancreatic and bile ducts after papillectomy. In addition, the presence of pancreas divisum can obviate the need for pancreatic duct stent placement.

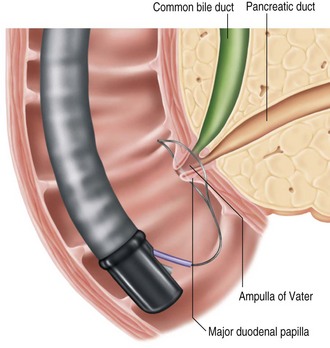

Endoscopic Papillectomy

Endoscopic resection is limited to the mucosa and submucosa of the duodenal wall and the tissue around the biliary and pancreatic duct orifices located at the major duodenal papilla.41 With endoscopic papillectomy it is difficult to remove tumor tissue invading the common bile duct or pancreatic duct. In clinical practice, the terms endoscopic papillectomy and ampullectomy are used interchangeably. However, ampullectomy consists of circumferential resection of the ampulla of Vater, with separate reinsertion of the bile duct and pancreatic duct into the duodenal wall. This necessitates a surgical duodenotomy and resection of pancreatic tissue in the area of the anatomic attachments of the ampulla to the duodenal wall.42 Therefore the term endoscopic papillectomy is more appropriate than endoscopic ampullectomy when endoscopic resection of ampullary lesions is performed.

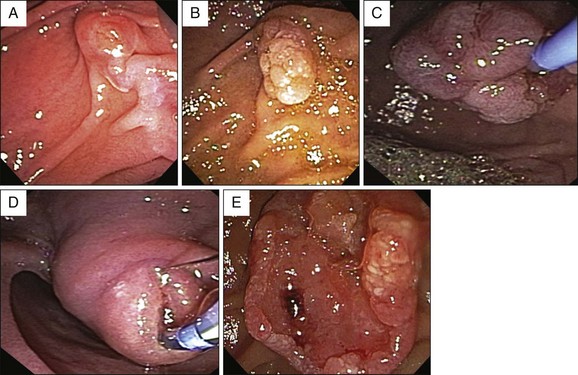

1 Snare Excision

Papillectomy is typically performed with a standard monopolar diathermic snare used for colonoscopic polypectomy. In most studies neither the size of the snare nor the direction of snaring are mentioned.5,9,10,43,44 Polypectomy snares of various diameters ranging from 11 to 27 mm are used, depending on the size of the lesion.11,27,45,46 Some authors prefer softer, more flexible snares (e.g., 2.5-cm AcuSnare, Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, N.C.) and some prefer a stiffer, more rigid snare (e.g., 2-cm oval snare with spiral wires, SnareMaster, Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, Pa.).47,48 The softer, more flexible snares allow easier manipulation over the elevator. A stiffer snare can be more easily positioned parallel to the plane of dissection and perpendicular to the catheter for a uniform excision to the level of the muscularis propria (Fig. 24.6). We prefer a softer snare for pedunculated or bulkier lesions and a stiffer snare for flatter, laterally spreading lesions. The lesion, together with the papilla, is grasped and excised using a blended current to decrease the risks of bleeding. Two studies have advocated snaring the tumor from the cephalad to the caudal side (snare apex placed at the superior margin of the lesion), citing that ensnaring the entire papilla was easier, although secure snaring is feasible from either direction.46,49

2 Electrosurgical Currents: Cutting versus Coagulation

There is no established consensus or guidelines regarding power output or the mode of electrosurgical current for endoscopic papillectomy, and in most studies these settings are not specified.50 When specified monopolar current was used in all studies,51–53 the power output ranged from 25 to 150 watts, usually with an effect of 2 or 3.10,11,27,52 The mode of the current also varied, with some authors using blended electrosurgical current and others using pure cutting current.5,27,52,53 The rationale for the use of pure cutting current is to avoid edema caused by the coagulation mode.2,9,33,51 In the absence of any randomized trials it is difficult to compare various power outputs and modes of current. In our practice, we use a monopolar, blended current at a setting of 25 watts.

3 En Bloc versus Piecemeal Resection

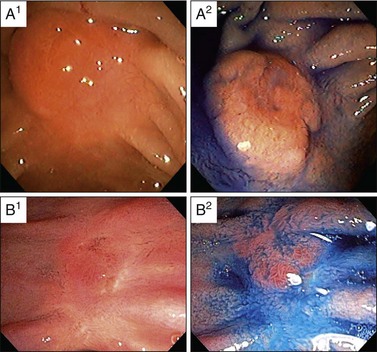

En bloc resection of the lesion should be attempted whenever possible, although no study to date has demonstrated a decreased incidence of tumor recurrence when en bloc rather than piecemeal papillectomy is performed (Fig. 24.7). However, based on general principles of oncologic surgery, en bloc resection is preferred due to a higher likelihood of complete tumor excision and better histologic analysis of the resection margins.51,54 En bloc resection can be technically more difficult and may incur a higher risk of bleeding and perforation, especially in the presence of one or more of the following: large tumor size, limited endoscopic accessibility, and laterally spreading lesions. In these cases, piecemeal resection may be undertaken, frequently with adjuvant ablative therapy, if needed. Also, piecemeal excision may require several sessions to achieve complete removal of the lesion.10 Vital dye staining with indigo carmine or methylene blue or use of narrow band imaging may help to delineate the tumor margins prior to resection (Fig. 24.8). In our center, when feasible, en bloc resection is performed; when this is not feasible, piecemeal resection is undertaken.*

4 Role of Submucosal Injection

Like other aspects of endoscopic papillectomy, the use of submucosal injection of either normal saline or dilute epinephrine remains somewhat controversial. Extrapolating from the practice of submucosal injection prior to mucosectomy there is a theoretical benefit that this reduces the risk of perforation and bleeding. The inability to “lift” the lesion after submucosal injection has been used by some to predict the presence of invasive cancer and preclude attempting an endoscopic papillectomy.46

If submucosal injection is performed, a sclerotherapy needle is used and the number of injections and total volume of solution varies with the size of the lesion.10 Methylene blue can be added to the solution to improve tumor visualization, especially the margins.54 However, ampullary tumors differ from mucosal neoplasms in other locations within the gastrointestinal tract because the biliary and pancreatic ducts are embedded and traverse the submucosa to emerge at the mucosal surface. A submucosal injection will fail to raise the lesion at the site of ductal insertion, making complete resection down to the sphincteric muscle difficult and potentially hindering subsequent access to the pancreatic and biliary ducts.56 Furthermore, submucosal injections may increase the risk of postprocedure pancreatitis. In the majority of series, submucosal injections have not been used. This does not appear to make complete resection difficult or increase the rate of adverse events.5,9,38,43,55 In our practice we do not perform submucosal injections unless dealing with large, laterally spreading lesions and, in these cases, submucosal injections close to the papilla are avoided.

5 Infrequently Performed Novel Techniques

Some novel but infrequently performed techniques to facilitate endoscopic papillectomy have been proposed. A few authors have reported successful resection of ampullary adenomas with intraductal extension using a balloon catheter linked to a snare with the inflated balloon in the common bile duct providing traction toward the duodenal lumen.51,57,58 To maintain pancreatic duct access after papillectomy, Moon et al.59 inserted a guidewire into the pancreatic duct before papillectomy in six patients with ampullary adenomas. A snare was passed over the wire and immediately after papillectomy a pancreatic duct stent was placed. More studies are needed to confirm the feasibility and safety of these inventive methods.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree