Chapter 19 Pancreatic Sphincterotomy

Since its initial application in 1974, endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy has revolutionized the approach to patients with biliary tract diseases.1 Using biliary sphincterotomy in conjunction with other techniques such as stent placement, balloon and basket extraction of stones, and stricture dilatation, biliary sphincterotomy has become the standard of care for problems that were once remedied only by surgical procedures. Endoscopic therapy for pancreatic disorders has not advanced quite as rapidly, however. The main reason for this seems to be the long-standing fear of inducing pancreatitis in an organ that frequently expresses its dislike for simple manipulation of the papilla and sphincter alone.2 Historically, pancreatitis and its associated adverse events have prevented some endoscopists from attempting to apply therapeutic techniques similar to those used in treating biliary tract disorders. In addition, clear-cut indications for endoscopic therapy of the pancreas have been much more difficult to define due to a paucity of well-designed clinical trials justifying its use. Most of the techniques that have been used in previous studies were performed on small numbers of patients, and in expert centers only. The majority of studies have been retrospective in design without control groups. There has been a deficiency in studies that use randomization and directly compare endoscopic therapy with either surgical or medical therapy.2

It is on this background that we begin to discuss endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy. This technique is the cornerstone of endoscopic therapy of the pancreas, and it provides initial access to the main pancreatic duct.3 Once access to the duct is obtained, it may be used as a single therapeutic maneuver (e.g., to treat pancreatic-type sphincter of Oddi dysfunction) or in series with other endoscopic therapeutic techniques, such as the placement of a stent across a ductal stricture.4 In chronic pancreatitis, for example, pancreatic sphincterotomy not only decreases pressure within the main pancreatic duct, but also may be used to facilitate the extraction of calculi and protein plugs.1

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Endoscopic Pancreatic Sphincterotomy

Preparation

As with all endoscopic procedures, it is imperative to obtain valid informed consent before beginning.5 This becomes of paramount importance when discussing with patients and their families the potential risks involved in performing an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with pancreatic sphincterotomy, as the adverse event rates are greater when compared with routine upper endoscopy. Routine blood work, including a complete blood count (CBC), and coagulation parameters are usually verified before the procedure. Aspirin, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), warfarin, and other anticoagulants are withheld for several days before and after the procedure, if possible.5 Antibiotics are frequently given 30 to 60 minutes before the procedure in an effort to prevent procedure-related infection such as biliary sepsis, but this is not standard at all institutions. The data supporting antibiotic prophylaxis prior to pancreatic or biliary sphincterotomy are sparse and very limited. Only a few studies have attempted to investigate this issue, and most of them have had small numbers with poorly defined endpoints.6 Nonetheless, many endoscopists will use antibiotic prophylaxis before (and frequently following) a planned endoscopic sphincterotomy. Coverage with a second- or third-generation cephalosporin appears sufficient. Broader spectrum antibiotics such as piperacillin/tazobactam, or vancomycin and gentamicin if there is a penicillin allergy, may be warranted in some instances.

Equipment

Pancreatic sphincterotomy, like biliary sphincterotomy, is performed with a standard side-viewing duodenoscope, the appropriate sphincterotome (papillotome), and an electrosurgical generator.7 There are a variety of options in terms of commercially available electrosurgical generators. Most have both monopolar and bipolar options, and they offer pure cutting, pure coagulation, and blended (cut/coag) current modes.5 These are the same generators that are used when performing polypectomies. Newer models even allow for cutting options that incrementally splice the sphincter muscle in 1-mm segments, informing the endoscopist with an audible alarm at the end of each segment. This attempts to ensure that the sphincterotomy is performed in a careful, stepwise fashion without producing an unintentional exaggerated cut. However, there are no data that verify the effectiveness of this method.

There is little evidence supporting the use of one current mode over the others during a sphincterotomy. Some data, however, suggest that pure cutting current may be associated with less post-ERCP pancreatitis when compared to blended current.8 Also, the pure cutting technique is thought to cause less fibrosis, thus helping to diminish the chance of developing future papillary stenosis. As a result, some endoscopists advocate using only the pure cutting mode when performing a pancreatic sphincterotomy. It is unclear as to whether there are truly more bleeding adverse events associated with this option, as some have suggested.

An enormous variety of sphincterotomes and guidewires are now commercially available for use in pancreatic sphincterotomy. For a more detailed description of all endoscopic guidewires and ERCP accessories, refer to Chapter 4. The original Demling-Classen or Erlangen pull-type sphincterotome (bowstring design) is still the most popular choice for performing a pancreatic sphincterotomy (Fig. 19.1). There are several variations of this type of sphincterotome; they are all based on differences in the length of the exposed cutting wire, the number of additional lumens, and differences in the length of the “nose” of the instrument.5,7 A shorter nose (5 to 8 mm beyond the wire) is sometimes more convenient for cannulation of the major papilla prior to sphincterotomy. It allows for easier engagement between the sphincterotome tip and the papilla without much interference from the cutting wire. Once the tip is positioned inside the papillary orifice, tension on the wire may be used to bow the tip into the correct axis and correctly align the instrument for eventual sphincterotomy.7 Sphincterotomes with longer noses (2 to 5 cm beyond the wire) lose their ability to bow since most of the cutting wire is retained inside the duodenoscope until deep cannulation is attained. The advantage of this type of sphincterotome is the ability to maintain cannulation while the wire is being withdrawn during sphincterotomy. However, now with triple-lumen cannulas and soft, flexible tip guidewires that cause less injury to the pancreatic duct, a guidewire can be easily left in place within the pancreatic duct in order to maintain cannulation while performing a pancreatic sphincterotomy (wire-guided sphincterotomy). This technique of wire-guided sphincterotomy is now considered the standard of care for both pancreatic and biliary sphincterotomy.

Fig. 19.1 Standard sphincterotomes used in pancreatic sphincterotomy.

(Reproduced by permission of Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Johns Hopkins Hospital.)

Standard sphincterotomes have a 5 Fr to 7 Fr catheter tip that can accept a 0.035-in guidewire.9 Use of a triple-lumen cannula allows for the placement of a preloaded guidewire and simultaneous contrast injection without having to remove the guidewire. When manipulating the papilla and the most proximal portions of the main pancreatic duct prior to sphincterotomy, many endoscopists prefer an ultratapered catheter tip (5 Fr-4 Fr-3 Fr) for easier cannulation. These sphincterotomes use smaller caliber guidewires, frequently down to 0.018 inch in diameter. Conversely, a special 3 Fr cannula can be passed through the channel of a standard sphincterotome to produce the effect of a tapered tip catheter.9

Endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy is performed after deep cannulation of the main pancreatic duct with a guidewire.10 There are several different types of commercially available guidewires that may be used to perform this technique. Such configurations of guidewires include conventional, nitinol, hydrophilic, and “hybrid.” The range in wire diameter is from 0.018 to 0.035 in.11 When performing a wire-guided pancreatic sphincterotomy, the hydrophilic-coated wires with soft and floppy tips may be helpful in preventing trauma to the main pancreatic duct or its side branches.10 As mentioned above, this deep wire-guided technique in pancreatic sphincterotomy has obviated longer nose sphincterotomes. Maintaining adequate cannulation of the papilla in this manner is less traumatic and more secure.

The Endoscopic Technique

The main principles involved in pancreatic sphincterotomy are very much like those of biliary sphincterotomy. They involve wire-guided cannulation of the duct prior to cutting and use a slow and stepwise approach that relies on accurate identification of anatomical landmarks. There are essentially two different types of techniques that are used by most expert endoscopists when performing this procedure. The first approach, and the more popular one, is performed while using a standard pull-type sphincterotome. The second approach uses an endoscopic needle knife to cut the sphincter muscle after placement of a pancreatic duct stent. Both techniques have their advantages and disadvantages, and the details surrounding each approach are discussed below. In addition, we will briefly describe the technique of precut or “access” pancreatic sphincterotomy in those instances when the endoscopist is faced with a difficult pancreatic cannulation. Sphincterotomy of the minor papilla is discussed separately in Chapter 20.

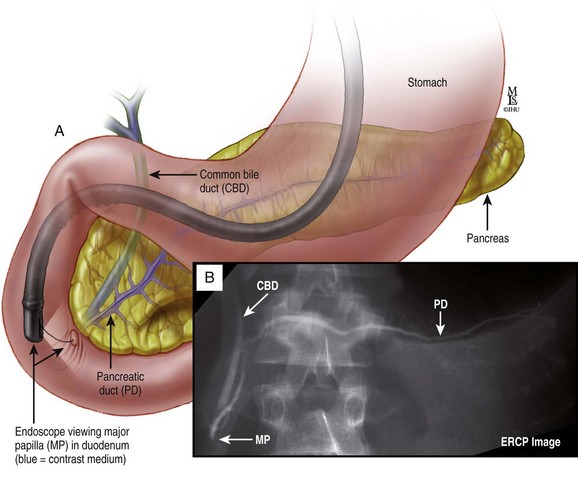

As with both biliary and pancreatic sphincterotomy, success starts with accurate cannulation of the correct duct. This is, at times, the greatest hurdle for novice therapeutic endoscopists. In general, selective cannulation of the pancreatic duct is easier than that of the biliary duct, assuming that there has not been a previous sphincterotomy. The reason for this is directly related to the anatomical axis of each duct in relation to the wall of the duodenum. Although the main pancreatic duct may be tortuous with multiple side branches, the most proximal portion of the duct courses away from the papilla at a 90-degree angle from the duodenal wall (Fig. 19.2). It then runs more toward the right and straight inside.12 The most distal part of the common bile duct, on the other hand, assumes more of an acute angle in its relationship with the duodenal wall. It extends in an upward and leftward direction from the papillary orifice. This provides for a more difficult cannulation, depending on how acute the angle of takeoff is from the papilla.

One must remember that a cross-sectional view of the inner portion of the ampulla of Vater (the part furthest from the duodenal lumen) is similar to a “double-eyed onion,” with each duct running off in its own unique direction.12 The most proximal portion of the ampulla, however, is a single orifice that leads from the lumen of the duodenum into a common channel. This common channel then merges with the so-called “double-eyed onion.” The length of this channel is variable but usually ranges between 1 and 10 mm.7 Within this channel are several folds of papillary mucosa that may often act as obstacles to selective cannulation with the sphincterotome. Therefore accurate cannulation depends on finding the correct axis with the catheter tip before the guidewire can be pushed all the way out into the main pancreatic duct. Approaching the papillary orifice with the right orientation allows the endoscopist to find the correct axis.

When aiming for the pancreatic duct, the catheter should enter the orifice perpendicular to the duodenal wall. Then, in order to traverse the correct plane, the catheter tip should be advanced along the floor of the orifice to find the pancreatic duct. This is in contrast to biliary cannulation, in which the catheter tip is aimed at the roof of the papillary orifice to find the distal common bile duct.7 The only way to ultimately assure correct cannulation is to (1) gently advance the guidewire into the duct and confirm fluoroscopically the position of the wire in a transverse direction toward the spine or (2) inject contrast to verify one’s position within the duct fluoroscopically. To limit the risk of pancreatitis, as little contrast as possible should be used in this situation.

The importance of correct ductal axis is paramount. When faced with a difficult cannulation of the pancreatic duct, one may have to lower the catheter tip even further once advancing along the floor of the papillary orifice. This can be achieved by lowering the elevator on the duodenoscope, thus pressing down on the floor.7 The injection of contrast is done simultaneously in an effort to correctly identify the pancreatic duct.

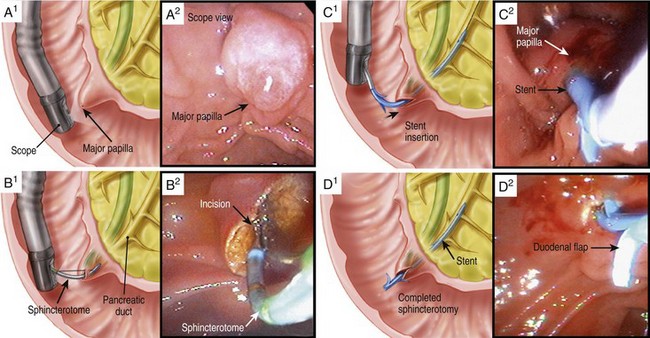

Pull-Type Sphincterotomy

After successful pancreatic cannulation and advancement of the guidewire into the main pancreatic duct, confirmation of position is usually obtained with a contrast pancreatogram. Assuming that a clear indication for sphincterotomy has been established, this part of the procedure is most often performed with a pull-type sphincterotome (as mentioned above). Like biliary sphincterotomy, the incision should be “hot and slow.”7 It should be directed toward the 1 to 2 o’clock position with the very distal part of the cutting wire.5,10 In other words, most of the cutting wire should be visible outside the papillary orifice. Note that the direction of the cut is very different from that of a biliary sphincterotomy (Fig. 19.3). In biliary sphincterotomy, the cutting direction is in the 11 to 1 o’clock position (preferably the 12 o’clock position). The sphincterotome is slightly bowed while the cutting wire is “walked up” the roof of the papilla in a stepwise fashion.7 In pancreatic sphincterotomy the same principles apply, but the direction is more toward the right, guiding the cutting wire along the floor of the papillary orifice.

The actual incision should be performed using the pure cutting current with the electrosurgical generator. This prevents further damage to the pancreas and limits the possible future development of fibrosis and papillary stenosis.10,13 The length of the cut is generally between 5 and 10 mm. Larger diameter ducts require longer cuts in order to achieve the largest possible access. Once the sphincterotomy has been completed, a temporary pancreatic stent is usually left in place for a short period of time in order to facilitate adequate drainage from the duct. The edema that ensues following a pancreatic sphincterotomy can cause ductal obstruction and eventual pancreatitis.14 This policy of placing a pancreatic stent after every pancreatic sphincterotomy, however, is not universal. Some expert endoscopists do not feel the need to perform this step. Moreover, the types of stents that are chosen and the desired duration of use have also been debated.15

Early in the era of pancreatic sphincterotomy, many endoscopists advocated always performing this procedure in concert with a prior biliary sphincterotomy. Biliary sphincterotomy done immediately before pancreatic sphincterotomy is felt by some to allow for easier identification of clear anatomical landmarks, thus making it a safer and more effective procedure. It may provide better exposure of the pancreaticobiliary septum and therefore allow improved access to the desired pancreatic tissue.16 Also, this technique prevents the rare possibility of biliary adverse events following a primary pancreatic cut.1 This includes inadvertent damage to the distal bile duct as well as possible biliary obstruction due to edema adjacent to the biliary duct orifice. Many expert endoscopists recommend a biliary sphincterotomy before a pancreatic sphincterotomy in cases of cholangitis or obstructive jaundice, a common bile duct diameter >12 mm, or an alkaline phosphatase level greater than twice normal.10 It may also be done when it is needed to obtain better access to the main pancreatic duct.17

When performing a pancreatic sphincterotomy after a biliary sphincterotomy, the anatomic landmarks are different. Part of the papilla has already been filleted open for this procedure and so the pancreatic orifice is usually seen at the 5 o’clock position near the right margin of the sphincterotomy.1 Transient opening of the pancreatic duct will allow for better visualization and more accurate cutting. This may be achieved by gently sucking air into the duodenum with the scope. Once the orifice is correctly identified and cannulated, the sphincterotomy can be carried out in a similar fashion as described above (Box 19.1).

Box 19.1

The Pull-Type Sphincterotome Technique

Direction of the incision is along the 1 to 2 o’clock position

Direction of the incision is along the 1 to 2 o’clock position

Pure cutting current should be used

Pure cutting current should be used

Incision should be “slow and hot”

Incision should be “slow and hot”

Majority of the cutting wire should be outside the papillary orifice

Majority of the cutting wire should be outside the papillary orifice

Length of the incision is generally between 5 and 10 mm

Length of the incision is generally between 5 and 10 mm

A pancreatic duct stent is inserted after completion

A pancreatic duct stent is inserted after completion

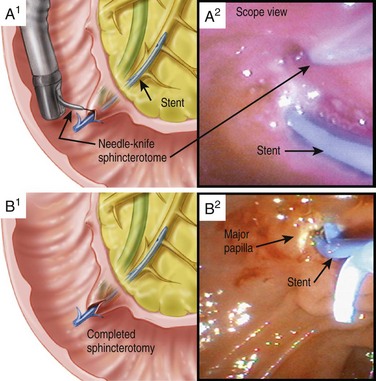

Needle-Knife Sphincterotomy

An alternative method to pancreatic sphincterotomy uses an endoscopic needle knife instead of a standard pull-type sphincterotome (Fig. 19.1).16 Cutting with the needle knife is done only after placement of a pancreatic duct stent. The tip of the needle knife is placed at the most proximal portion of pancreatic sphincter tissue that is overlying the stent. Using the stent as a guide to direct the cut along the plane of the pancreatic duct, the needle knife tip is advanced over the top of the stent and down its longitudinal axis (Fig. 19.4). Incision length is similar to that of sphincterotomy with a pull-type sphincterotome; that is, the length is generally between 5 and 10 mm. Many experts believe that a prior biliary sphincterotomy is especially helpful before using this needle-knife technique.16 Good exposure of the pancreaticobiliary septum allows for better tissue access and more effective “septotomy.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree