Fig. 19.1

Modified anchor trocar placement for pelvic surgery

Fig. 19.2

Extraction site with wound protector in place

An angled video or flexible-tip laparoscope is required for adequate exposure of relevant anatomic structures during left colon and rectal mobilization. Atraumatic instruments should be used, though careful vigilance for inadvertent injuries to abdominal structures even with these instruments should be maintained. The dissection can be accomplished in a number of different methods but is most commonly performed with a bipolar energy device or monopolar electrocautery and vascular staplers or clips. What is used is probably less important than the surgeon consistently using a technique that is reproducible, reliable, and comfortable. One important pearl to keep in mind in choosing a dissecting instrument is selecting one instrument that allows for both dissection and vascular division that will significantly ease the case flow and increase the speed of the procedure by minimizing the number of instrument exchanges.

Medial-to-Lateral Left Colonic Dissection

The most common and easiest technique employed for mobilization of the left colon is the medial-to-lateral approach and will be discussed in detail. Many other techniques have been described including the lateral-to-medial and sub-IMV to accomplish the same goals. As the surgeon becomes facile with the medial-to-lateral approach, it is beneficial to add these other techniques to the surgical repertoire. There will be occasions, especially as the surgeon gains experience and begins to utilize minimally invasive techniques for more difficult cases, where these other techniques may provide the only approach that can allow successful completion of a laparoscopic procedure.

Retroperitoneal Exposure/Critical Anatomy

The initial step in the medial-to-lateral dissection is identification of the inferior mesenteric (IMA) and superior rectal arteries (SRA), as this will allow entry to the avascular retroperitoneum. Grasping the mesenteric edge of the mid-sigmoid colon and elevating it superiorly and caudally most easily accomplish this (Fig. 19.3a–c). The video laparoscope can be angled inferiorly (down) to best expose this anatomy. The base of the sigmoid mesentery can then be incised accessing the retroperitoneum (Fig. 19.4a–c).

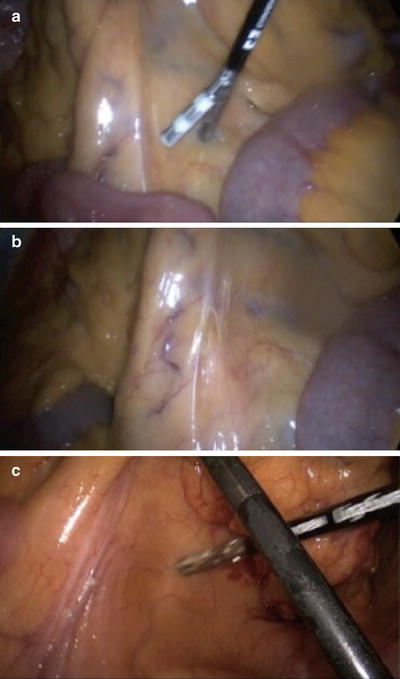

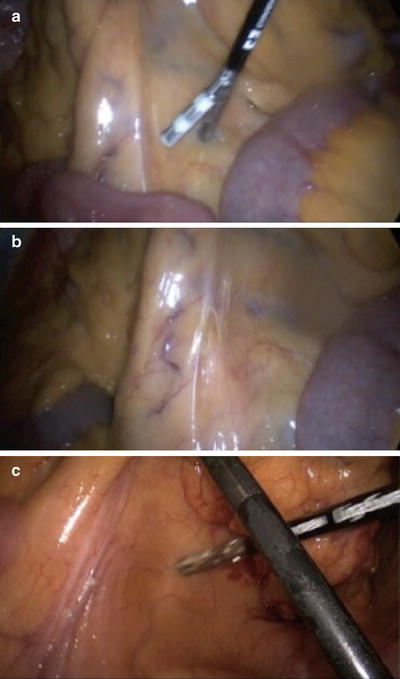

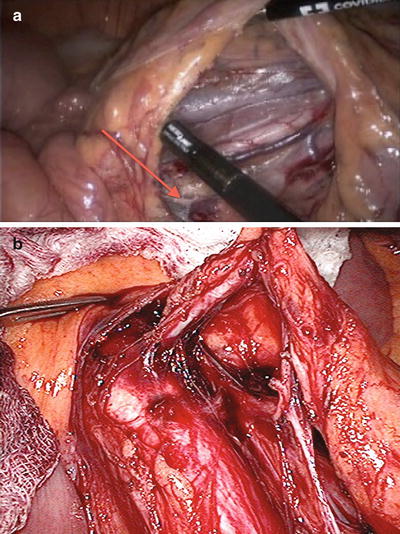

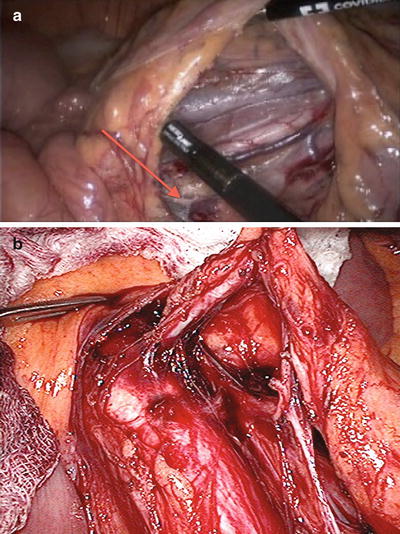

Fig. 19.3

Medial-to-lateral mobilization. (a) Elevation of the IMA/SRA toward the abdominal wall; (b) scoring the peritoneum overlying the vessel; (c) caudal (i.e., pelvic) traction places the vessel on stretch and allows it to be clearly seen to identify the correct plane

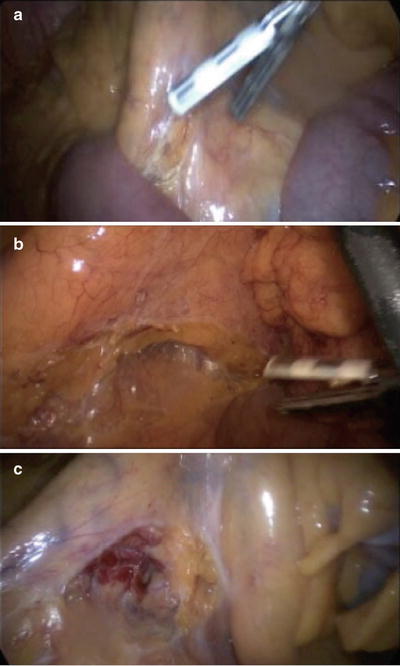

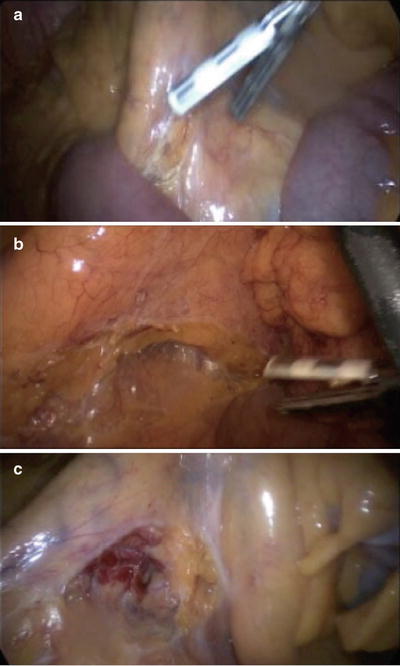

Fig. 19.4

Base of the sigmoid mesentery. (a) Scoring over mesentery, (b) broad opening of a plane toward the sacral promontory, (c) deeper medial-to-lateral dissection

After incising the retroperitoneum, the next step is identification of the hypogastric (sympathetic) nerves and left ureter and gonadal vessels. The hypogastric nerves are typically apparent running just inferior to the superior hemorrhoidal artery. These structures can be bluntly dissected inferiorly into the retroperitoneum away from this vessel and the root of the IMA (Fig. 19.5a, b). After this is performed, the surgeon then identifies the left ureter and gonadal vessels (Fig. 19.6). It is important to remember that the retroperitoneum curves anteriorly or away from your line of vision as the dissection progresses laterally. The surgeon must sweep the retroperitoneal tissue off the inferior aspect of the colonic mesentery to avoid mobilizing the ureter and gonadal vessels superiorly with the colon. The exposure, visualization, and dissection is facilitated by creating as large of an opening as possible underneath the SRA, as this greatly increases the mobility of the SRA and sigmoid colon mesentery. The video laparoscope can be angled superiorly (upward) to peer under the SRA and expose this plane. Additionally, the proper technique to minimize trauma and bleeding in the retroperitoneum is to dissect in the superior-inferior plane and not laterally. Dissecting in the lateral plane (i.e., tangential to the retroperitoneum) often results in tearing of retroperitoneal structures and causes nuisance bleeding.

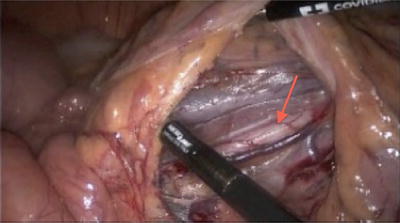

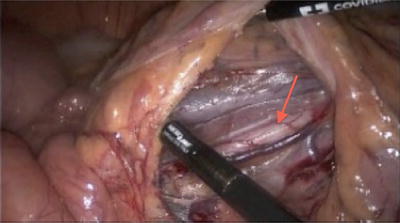

Fig. 19.5

(a) Hypogastric nerves (arrow) swept posteriorly to the retroperitoneum near the base of the IMA. (b) Another view of the hypogastric nerve at the base of the IMA. With permission from Jeffrey W. Milsom, Bartholomäus Böhm, and Kiyokazu Nakajima. Laparoscopic Anatomy of the Abdominal Cavity. In: Jeffrey W. Milsom, Bartholomäus Böhm, and Kiyokazu Nakajima, eds. Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery. Springer, New York, 2006:pp104. © 2006 to Springer

Fig. 19.6

Left ureter (arrow) coursing medially to the gonadal vessels

Utilizing these techniques often results in easy identification of the relevant retroperitoneal structures; however, on occasion the left ureter can be difficult to find. In this case, several maneuvers can be helpful. First, carefully examine the inferior aspect of the colonic mesentery to ensure that the left ureter has not been mobilized off the retroperitoneum. Second, clear the lateral aspect of the base of the IMA and then carefully dissect laterally away from this vessel in the retroperitoneum. Finally, carry the dissection inferiorly to the pelvic brim to the level of the common iliac artery bifurcation and identify the ureter as it crosses this vessel. If the ureter cannot be identified using these maneuvers, the dissection can be altered to access the retroperitoneum at the level of the inferior mesenteric vein or by the lateral-to-medial approach. Finally, if the ureter still cannot be identified, then conversion to open is likely indicated.

Vascular Pedicle Division/Proximal Colonic Mobilization

After the left ureter and gonadal vessels are identified, safe vascular division can be performed. This is most typically performed with bipolar electrocautery, vascular staplers, or endoclips. Angling the video laparoscope to peer leftward often facilitates this exposure. The majority of surgeons use the bipolar energy device to both dissect and divide vasculature, thereby speeding the overall procedure (Fig. 19.7). Once the IMA is divided, then the mesentery can be elevated off the retroperitoneum with blunt dissection in the superior-inferior plane. The anatomic structure guiding this dissection is Gerota’s fascia (Fig. 19.8), which can be bluntly dissected inferiorly to ensure that the left kidney is not mobilized off the retroperitoneum. Importantly, as the surgeon develops the plane over the superior aspect of the left kidney, it is important to consciously continue the dissection superiorly and not follow the curve of the kidney inferiorly. This will ensure that inadvertent injury, i.e., bleeding, resulting from injury to the left adrenal gland or its vasculature does not occur. Additionally, it ensures that the dissection will continue superiorly to the pancreatic tail (Fig. 19.9), thus dividing the retroperitoneal attachments to the splenic flexure, which is important for gaining colonic length and avoiding problematic bleeding in the retro-pancreatic space. Also, the plane should be developed lateral to the body of the colon to facilitate detachment of the colon from its lateral attachments performed later in the procedure (Fig. 19.10). Maintaining tension is the key to this dissection as it is an avascular plane and separates easily with adequate tension.

Fig. 19.7

Division of the IMA pedicle using an energy vessel sealing device

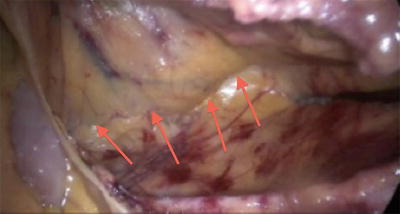

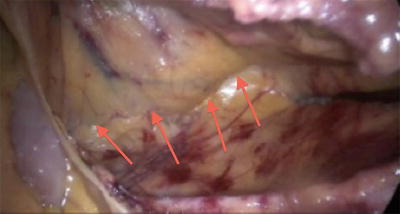

Fig. 19.8

Arrows marking the line of dissection between the retrocolonic mesentery and the retroperitoneum and Gerota’s fascia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree