Open Cholecystectomy With Choledochotomy and Common Bile Duct Exploration

Mark P. Callery

Lygia Stewart

Open Cholecystectomy

Indications/Contraindications

In the last 20 years, the clinical indications for cholecystectomy have not changed, but the operative approach has. Biliary colic, acute/chronic cholecystitis, gallstone pancreatitis, and cholangitis, in that order, remain the most common indications. Another important entity is biliary dyskinesia, as diagnosed by HIDA scan. Most agree a gallbladder ejection fraction below 40% supports the diagnosis, especially when pain occurs during cholecystokinin injection. There are however some patients where surgical treatment of asymptomatic gallstones is indicated. These include patients with diabetes mellitus, transplant patients, patients with chronic liver disease, patients undergoing bariatric operations, patients undergoing other gastrointestinal operations, patients with sickle cell anemia or other chronic hemolytic anemia, and patients with a potentially increased risk of gallbladder carcinoma.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is our preferred method of removing the gallbladder regardless of the indication. Open cholecystectomy can be performed in conjunction with another open procedure or become the fall-back option particularly in the following scenarios:

Patients who may not tolerate the physiologic changes associated with the pneumoperitoneum (COPD, CHF) Open cholecystectomy may be lower risk

Patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension (relative contraindications)

Third trimester of pregnancy

Type II Mirizzi Syndrome (Cholecystobiliary fistula)

Gallbladder cancer (suspicion or confirmed)

Purulent or gangrenous cholecystitis or previous upper abdominal procedures are no longer absolute indications for an open approach. Surgeons must carefully weigh the feasibility and safety relative to disease severity. Acute cholecystitis in this subset of patients can be effectively managed with percutaneous cholecystostomy as a less invasive but effective alternative. In many cases, elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be performed once the severe illness subsides, and the patient is physiologically improved. Recurrent biliary symptoms occur in 9% to 33% of patients who do not have a subsequent cholecystectomy. In some, operation can be entirely avoided.

Converting to Open Cholecystectomy

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is not always possible or safe in some patients. Conversion to open cholecystectomy becomes necessary. Biliary injuries are more likely to occur during difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomies, no different than with open operations. When laparoscopic cholecystectomy is performed for acute cholecystitis, biliary injuries occur three times more often than during elective laparoscopic cases, and twice as often compared to open cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis.

Is conversion as easy as it seems? Perhaps for some, but certainly not all. The reality is that open cholecystectomy has been far less frequently performed over these past 20 years. Trainees during this period presumably received valid instruction and proctoring for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, but rarely for open cases. Established surgeons needed to command the laparoscopic operation to compete, all the while potentially diluting their comfort with the open variant. Finally, there is the pressure and patient expectation for rapid recovery. Two very different operations lead to two scenarios which, though not proven, could subtly account in part for static biliary injury rates. Because of inexperience, the surgeon ignores or resists the sensible default option to convert, does not and incurs injury. In other instances, the surgeon overextends laparoscopic experience when disease severity warrants conversion, and incurs injury. Is open cholecystectomy becoming a specialty operation? No. The anatomical considerations of cholecystectomy are constant regardless of open or laparoscopic approach, and a talented surgeon has these to abide by for safety.

Technical Principles of Open Cholecystectomy

Preoperative Planning and Positioning

During informed consent, every patient should understand that conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy may occur. Patients are positioned supine with their right arm tucked. If you anticipate an open procedure, alert the anesthesia team, request the scrub team to have open case instruments available if not open, and make your trocar stab incisions deliberately along a predrawn right subcostal incision line. Unless you need to control bleeding, enter the RUQ deliberately and not stressed by your decision to convert. Make sure everyone is ready for what lay ahead, and clear that it will not be much if at all easier.

Technique and Pertinent Anatomy

Some favor a right subcostal incision with careful entry across the fascia below the ribs (1 to 2 cm) to insure durable closure. Some prefer an upper midline incision.

Whatever your choice of retractor, be certain the right ribs can be elevated, and deep partitioning of the RUQ can be achieved with packs and retractors. The liver can be brought down with packs above its right lobe. Segment IV can be elevated to reveal the porta hepatis. The hepatic flexure of the colon can be partitioned inferiorly. The stomach can be retracted medially. Unless you need explore the common bile duct (CBD), you can forego kocherizing the duodenum.

Now exposed, how should you tackle the gallbladder? Assuming you will, you may decompress it via a trocar and suction.

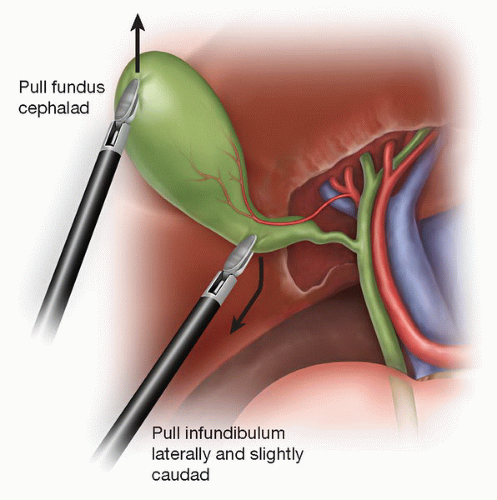

A Kelly clamp can be placed on the fundus for lateral/up retraction. Another Kelly is carefully placed lower on the infundibulum for lateral/down retraction to create an angle between the cystic duct and CBD (Fig. 14.1).

An antegrade/top-down or retrograde/infundibulum-up technique is surgeon choice, but often determined by the anatomy and disease conditions.

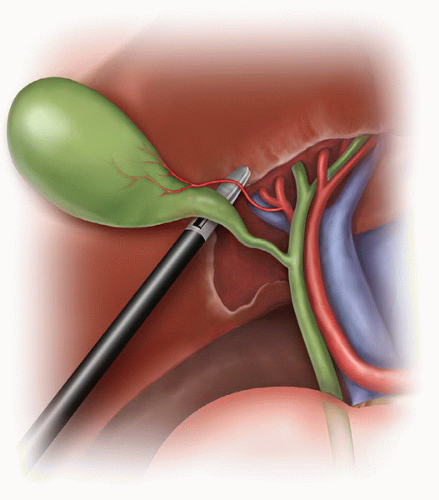

There must be positive identification of the cystic duct and artery as they join the gallbladder infundibulum before they can be divided.

From the technique standpoint, how is this achieved? As with laparoscopic cholecystectomy, some advocate intraoperative cholangiography (IOC), the infundibular technique, and the critical view technique. We recommend the critical view technique of Strasberg. It is dictated by porta hepatis/gallbladder anatomy, and not access technique of the operation. It fully applies to open cholecystectomy.

Critical View Technique—consists of tentative identification of the cystic structures by dissection in the anterior and posterior aspects of Calot’s triangle, followed by dissection of the gallbladder well off the liver bed. The surgeon achieves conclusive identification of the cystic structures as the only two structures entering the gallbladder, eliminating the possibility of misidentification (Fig. 14.2).

It is not necessary or recommended to see the CBD. “Tenting injury” of the CBD in fact can occur especially if there is a parallel junction of the cystic duct with the CBD.

Some argue that this critical view technique requires more dissection, and so the opportunity for injury still exists. Once the critical view is attained, however, the cystic structures can be occluded and divided, as they have been positively identified.

Failure to achieve this critical view warrants cholangiography to define ductal anatomy.

Surgeons should indicate in dictated operative notes for both open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy precisely how they identified the cystic structures for division.

Advocates of routine cholangiography at open cholecystectomy argue that they identify unsuspected CBD calculi and clarify biliary anatomy. Opponents point out that routine cholangiography leads to unnecessary common bile duct explorations (CBDEs) because of false-positive results and only adds time and cost to the procedure. Cholangiography can also cause direct injury to the bile duct or surrounding structures unless performed properly. There are no large prospective randomized trials that answer the question definitively, so most practicing surgeons perform IOC selectively.

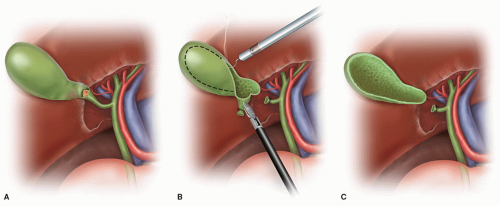

After an arduous dissection in Calot’s triangle, a surgeon may rush the gallbladder removal from the liver, but beware. Avoidance of ductal injury in the liver bed depends upon staying in the correct plane of dissection, and patience combined with meticulous technique and experience will ensure safety.

In some cases of acute cholecystitis, the gallbladder “shells out” relatively easily from its edematous intrahepatic bed. In other cases, and especially in chronic cholecystitis, the dissection of the gallbladder out of the liver bed can be tedious, frustrating, and quite bloody. Hemostasis can take some time, and many tricks (argon beam, cautery, packing, hemostatics) to achieve, but one must do so. Subtotal cholecystectomy (leaving the hepatic side gallbladder wall) is always a valid option (Fig. 14.3).

We use postoperative drains selectively but liberally. Conclude by cleaning up the RUQ, re-assuring hemostasis, and closing the incision and skin.

We use perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis for open, but not laparoscopic, cholecystectomy. Any NG Tubes are removed.

When dictating the operative note, specify the circumstances of conversion to open cholecystectomy, stressing safety and surgical judgment.

Postoperative Management

Typically, recovery from open cholecystectomy is more rapid than other open abdominal procedures. Awareness of complications is paramount, but with none, limited size

incisions heal well, diets can be advanced within 1 to 2 days, and discharge by 3 to 4 days. Full activity is resumed gradually over ensuing weeks, with restricted weight lifting for 6 weeks.

incisions heal well, diets can be advanced within 1 to 2 days, and discharge by 3 to 4 days. Full activity is resumed gradually over ensuing weeks, with restricted weight lifting for 6 weeks.

Complications

Hemorrhage, intra-abdominal abscess and the full-spectrum of bile duct injuries are the most significant postoperative complications of open cholecystectomy. Other less frequent complications include retained bile duct stones, bowel obstruction, hepatic dysfunction, pancreatitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and the need for reintervention (<1% of patients).

Sources of intraoperative bleeding include the liver bed, hepatic artery and its branches, a replaced right hepatic artery (which courses to the right of the CBD), and the portal vein as well. Most hemorrhage sources are controlled intraoperatively. Rarely postoperative bleeding may result in a self-contained subhepatic hematoma or serious hemoperitoneum with shock.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree