Fig. 24.1

(a) Operative positioning of patient for APR in lithotomy position. (b) High lithotomy position used for this technique

Securing the Radial Margin in Low Rectal Cancer

Although total mesorectal excision (TME) and improved anastomotic methods have enhanced the indications for and success of sphincter-preserving surgery (SPS), many low rectal cancers are better treated by APR. In the setting of T2/T3 tumors that invade the anal sphincters, APR is required in order to obtain negative radial and distal margins. In the setting of bulky T3 and T4 tumors that penetrate the muscularis propria and abut or invade the levator muscle, ultralow SPS requires opening of the hiatus between tumor and levator down to the anal sphincter. This can lead to tumor spillage and local recurrence [14].

Variations in the Surgical Plane

Standard Abdominoperineal Resection

Three variations of standard APR can be described based on the plane of dissection in the perineal phase.

Intralevator

This procedure is equivalent to the conventional APR described in the last decade [5, 10, 15, 16]. Dissection of the mesorectum is taken down close to the anorectal ring, opening the space between the rectum and the levator ani muscles (pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and ischiococcygeus) (Fig. 24.2a). The levator muscles are transected medially, near the anal canal. Most of the levator muscle and adipose tissue in the ischiorectal fossa is preserved. This procedure minimizes removal of tissue from the deep perineal space, but compromises radicality around the low rectum and anal canal. It may be successful for treatment of benign disease and low T1/T2 cancers without extrarectal spread, but it is not advisable in the setting of more advanced tumors [17].

Fig. 24.2

Comparison of the three surgical planes for APR. (a) Intra-levator APR for mid-low T2-3 rectal cancer without levator invasion but wide radial margin inside the levator (dotted lines). (b) Extra-levator APR for T3-4 rectal cancer with levator invasion (dashed lines). (c) Wide perineal resection for T4 rectal cancer at low rectum or anal canal, penetrating the levator or the external sphincter to the ischiorectal fat (solid line)

Extralevator

This procedure is equivalent to the cylindrical or extralevator APR, as described in the last decade [5, 10, 16]. Abdominal dissection of the mesorectum stops at the origin of the levator muscles (tendinous arch of the obturator internus muscle). The perineal surgeon makes a conservative incision around the anus, dissects along the outer border of the anal sphincters and levator muscles, enters the pelvis anterior to the coccyx, and resects the levator ani muscles from below. The lower rectum, the entire funnel-shaped levator ani musculature, and the anal canal are resected in continuity. The adipose tissue in the ischiorectal fossa is preserved, limiting dead space in the perineal closure (Fig. 24.2b). Indications for this procedure are radical resection for low T2/T3/T4 cancers that threaten to invade the anal sphincters or levator ani, but show no evidence of infiltration into the ischiorectal adipose tissue or perineal skin.

Wide Perineal Resection

This procedure is equivalent to the original Miles APR described in the early twentieth century [18, 19]. Abdominal mobilization of the mesorectum stops at the top of the levator muscles, as is done in the extralevator APR. The perineal surgeon makes a wide skin incision around the anus. The adipose tissue of the ischiorectal fossa is resected, along with the anal sphincters, by outward dissection toward the ischial tuberosities. The rectum, the entire funnel of levator ani muscles, anal canal, ischiorectal fat, and a portion of perineal skin are completely resected (Fig. 24.2c). In many cases there is insufficient tissue for perineal closure, and myocutaneous flap repair is required [16, 20]. This procedure is indicated in the setting of low T3 or T4 lesions that invade or penetrate the levator ani and/or external sphincter muscles. Tumors that invade the perineal skin also require wide perineal resection. For posterior tumors that penetrate the rectal wall and abut or invade the coccyx, a complete resection of the ischiococcygeus muscle and coccyx is required (Fig. 24.3) [21]. Removal of these posterior structures is not routinely required in the setting of small or anteriorly located tumors.

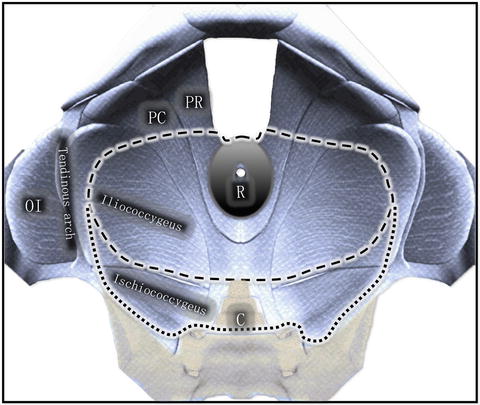

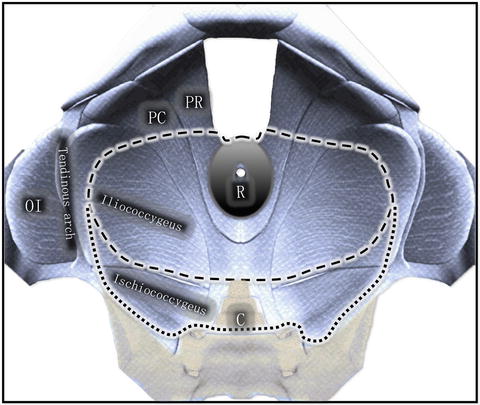

Fig. 24.3

Surgical planes for APR with normal levator resection or extended posterior levator resection plus coccygectomy. C coccyx, OI obturator internus, PC pubococcygeus, PR puborectalis, R rectum

The types of procedures and associated extent of resection are shown in Table 24.1. In tailored decision-making, these three variations of standard APR can be combined according to the quadrant of tumor location, to avoid unnecessary resection of normal tissue and delayed perineal healing. Precise preoperative examination and imaging are critical in optimizing the surgical dissection.

Table 24.1

Comparison of three APR procedures

Procedure | Also known as | Levator resection | Tissue in ischiorectal fossa | Perineal skin defect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Intralevator APR | Conventional APR | Partial | Preserved | Minora |

Extralevator APR | Cylindrical or Extralevator APR | Complete | Preserved | Minora |

APR with wide perineal resection | Miles’ procedure | Complete | Resected | Largeb |

Extended Abdominoperineal Resection

In selected cases an APR with multivisceral resection such as seminal vesiculectomy or prostatectomy in male patients, or partial vaginectomy in female patients can preserve urinary function without compromising the principles of en bloc R0 resection. Extended perineal dissections that include portions of the penis, scrotum, vulva, and pubic rami are sometimes required in the setting of bulky perineal tumors.

In summary, surgical dissection for an APR candidate should be planned preoperatively by high-quality imaging and thorough physical examination. It must be accomplished with strict attention to tumor size and location, circumferential margin, distal margin, and invasion of the levator muscle and adjacent organs.

Positioning of the Patient

Patients are anesthetized in the supine position and then moved downward until the iliac spine reaches the lower edge of the operating table. A gel pad can be placed beneath the upper/mid-sacrum to elevate the buttocks and facilitate skin preparation. The buttocks should protrude from the end of the operating table, providing adequate exposure of the perineum [22].

The stirrups should be placed as low as possible on the rail of the operating table, so that they do not interfere with the position of the surgeon or assistants during the abdominal part of the procedure. The patient’s legs are placed in the stirrups and aligned and padded properly to avoid pressure on the common peroneal nerve and popliteal artery [22]. Hyperflexion of the hip joints should be avoided to avoid excessive traction impinging on the sciatic nerve. Appropriate fitting of the leg in the stirrup is particularly important in obese patients, because excessive compression can lead to compartment syndrome [23]. When positioning is completed, the surgeon should reconfirm tumor location by digital exam and/or endoscopy. An irrigation-suction system is used to lavage the anal canal and rectal lumen, mitigating contamination in case of intraoperative bowel perforation. Following irrigation, the surgeon performs a double purse-string suture to close the anus.

Abdominal Phase of Abdominoperineal Resection

Abdominal Incision

A midline incision below the umbilicus is optimal in APR and can be used in most cases. A transverse or Pfannenstiel incision, which causes less pain and is cosmetically more appealing, may be used in selected patients. When a rectus muscle flap is required to close the perineal wound, it is necessary to make a midline incision. Exposure of the pelvis is achieved with self-retaining retractors. After entering the abdomen, exploratory examination is necessary to rule out extrapelvic metastases, particularly peritoneal dissemination.

Sigmoid Mobilization

The small bowel is packed into the upper abdomen. Retracting the sigmoid colon medially exposes the lateral peritoneal reflection (the white line of Toldt). Mobilization begins along the left pelvic brim, using sharp dissection with electrocautery or scissors. Upon entering the retrosigmoid space, the left ureter and gonadal vessels should be identified and pushed lateral to the mesocolon. Dissection in this space reaches the brim of pelvis. Dissection beyond the lower descending colon is rarely necessary, as the proximal sigmoid colon is generally sufficient for constructing a colostomy. Next, the right lateral peritoneum is incised over the sacral promontory, and extended cephalad toward the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery. In general, the right ureter is well lateral to the incision and does not require exposure. Incisions on both sides are extended caudally, beyond the sacral promontory to the upper rectum.

Low Ligation of the Inferior Mesenteric Artery

A typical ligation includes superior rectal artery/vein and the first trunk of sigmoid vessels. Additional ligation of vessels depends on the redundancy of the sigmoid colon [24]. The root of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) should be mobilized and palpated to discern any suspicious lymph nodes. Clinically positive lymph nodes should be removed [25]. The surgeon must be cautious when mobilizing the IMA to avoid injuring the sympathetic nerves of the hypogastric plexus and/or the left ureter.

Transection of the Sigmoid Colon

Following ligation of the major vessels, the sigmoid mesocolon is divided at the level chosen to create the end-sigmoid colostomy. The proximal end of the divided sigmoid or descending colon should be sufficiently mobilized to ensure a tension-free, well-vascularized colostomy. The sigmoid colon is then transected using a linear stapler. Anterior retraction of the lower sigmoid colon exposes the retrorectal space and facilitates identification of the preaortic/hypogastric sympathetic nerves and the origin of the hypogastric nerves.

Mobilization of the Upper Rectum

By retracting the lower sigmoid and rectum anteriorly away from the sacral promontory with tension, the plane between the visceral and pleural layer of the pelvic fascia can be sharply divided with minimal hemorrhage. The surgical plane should be developed anterior to the hypogastric nerve trunks. Tight adhesion between the hypogastric nerves and mesorectum requires meticulous dissection [26]. If the tumor invades unilateral or bilateral nerve trunks posteriorly, an en bloc resection is required. Injury to the hypogastric nerve trunks can lead to ejaculatory dysfunction in male patients.

Mobilization of the middle and low rectum comprises anterior dissection, posterior dissection, and management of the lateral ligaments. Some surgeons completely mobilize posteriorly in the presacral plane before starting the lateral or anterior dissection. However, release of the anterolateral peritoneal attachments as an initial maneuver provides mobility and better exposure of the retrorectal space. This also prevents tearing of the anterior rectum and tumor cell spillage, and provides better definition of the lateral ligaments. Suture retraction of the bladder in men or the uterus in women improves exposure of the pelvic cul-de-sac. Anterior dissection of the mid-rectum begins by incising the peritoneal reflection at the level of the seminal vesicles or vagina. Denonvillier’s fascia is identified and dissection continues in front of it, reaching the level of the upper prostate or mid-vagina [27].

Following the anterior dissection, the rectum can be more ventrally retracted. Two layers of pelvic fascia converge to form the recto-sacral fascia (Waldeyer’s fascia), which presents as firm fibrous ligaments at the S3/4 level. This fascia should be cut close to the mesorectum with electrocautery and followed to the tip of the coccyx. Accurate dissection of the lateral ligaments requires firm retraction of the rectum to the contralateral side. The middle rectal vessels, if present, must be ligated at their attachment at the visceral pelvic fascia. This prevents injury to the inferior hypogastric plexus and the urogenital nerve bundle, which crosses the middle rectal vessels and fans out behind the seminal vesicles or posterior vaginal wall.

Levator Resection in the Abdominal Phase

Following lateral dissection carried to the origin of the levator muscle, the lateral attachment of the iliococcygeal muscle to the tendinous arch of the obturator internus can be exposed, and partially or completely incised by electrocautery to establish the plane of extralevator resection (Fig. 24.3) [28]. When possible, release of the iliococcygeal muscle should begin on the tumor-free side, exposing the adipose tissue in the ischiorectal fossa. If the exposure is adequate, this initial release of the levator muscle can be extended anteriorly and medially to include the pubococcygeus. The levator dissection can then continue posteriorly through the ischiococcygeus muscle toward the coccyx. It should be noted that the posterior attachments of the levator muscles cover much of the anterior surface of the coccyx. Therefore, the ischiococcygeus muscle may be resected with the coccyx (for a posterior tumor) or divided and separated from the coccyx (for an anterior tumor), as required for a clear posterior surgical margin. Having established these anatomic landmarks in the pelvic floor, the surgeon may then complete the levator dissection near the tumor with added confidence.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree