Obturator Hernia

George C. Sotiropoulos

Arnold Radtke

Ernesto P. Molmenti

History and Anatomy

Reported original descriptions of obturator hernias date back to Le Maire in 1718 and Pierre Roland Arnaud de Ronsil in 1724.

The obturator area is delimited superiorly by the superior pubic ramus, inferiorly by the origin of the adductor magnus at the adductor tubercle of the femur, laterally by the hip joint and femur, and medially by the adductor and gracilis muscles, pubic arch, and perineum.

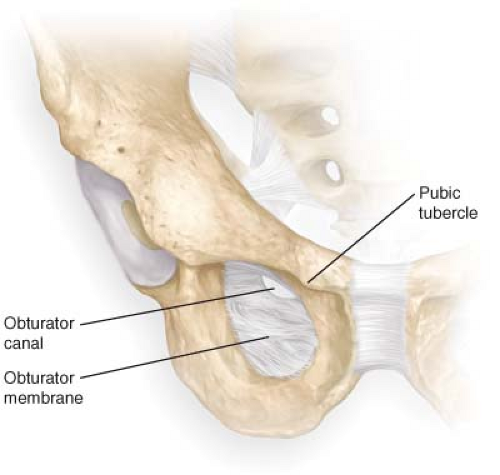

The obturator foramen is the largest bony foramen in the human body. It is formed by the rami of the ischium and pubis and, except in the area of the obturator canal, is covered by the obturator membrane. From an embryologic point of view, since the foramen and membrane represent an area of incomplete bone formation, the obturator foramen is a lacuna while the obturator canal is the real lumen (Fig. 10.1).

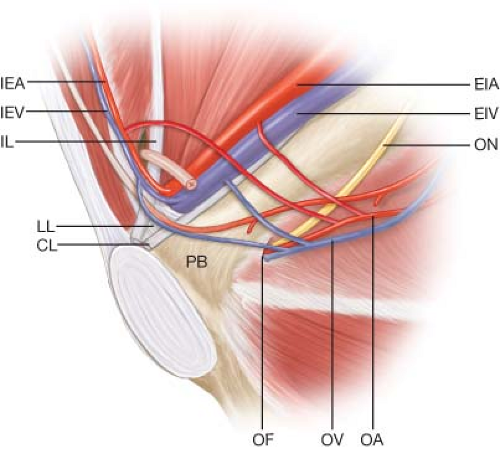

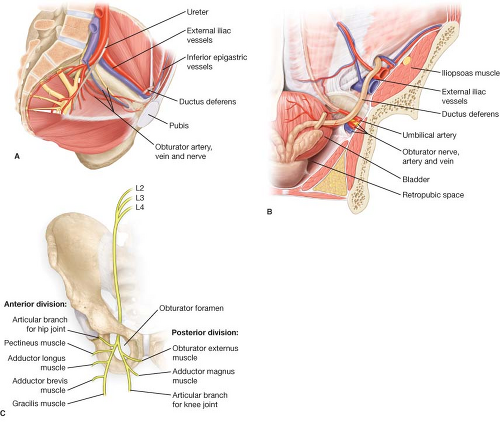

The obturator canal is 2 to 3 cm in length and originates at the obturator membrane in the pelvis. Its course is oblique and downward toward its termination in the obturator region of the thigh. The boundaries of the obturator canal are the obturator groove of the pubis above and laterally, and the internal and external obturator muscles and free edge of the obturator membrane inferiorly. The canal contains the obturator artery, vein, and nerve. The obturator artery divides to form a ring encircling the foramen and usually irrigates the head of the femur (Fig. 10.2).

The obturator nerve originates from the anterior divisions of L2 to L4. It arises beneath the psoas muscle, crosses the pelvic brim to the area where the common iliac vessels divide into external and internal branches, and subsequently travels downward toward the obturator foramen. Within the obturator canal, it travels above the obturator artery and vein. It represents the main nerve supply to the adductor compartment of the thigh and the obturator externus. As it exits the obturator canal, it divides into an anterior and a posterior division. Its anterior division innervates the gracilis and adductor longus. Its posterior division supplies the adductor brevis and anterior part of the adductor magnus. Hernia sacs may associate with either division of the obturator nerve. It provides sensory innervation for the intermediate part of the medial surface of the thigh and some innervation to the knee joint. The accessory obturator nerve (when present) travels over the superior public ramus and behind the femoral sheath to supply the pectineus muscle (Fig. 10.3).

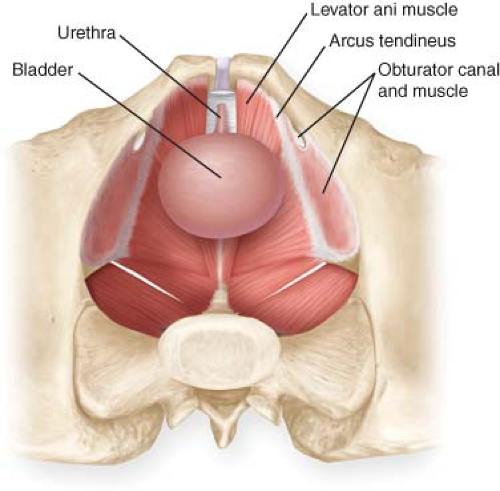

The obturator internus muscle, supplied by the L5 and S1 nerves, abducts the thigh when flexed, and rotates laterally the extended thigh. Its pelvic surface forms the lateral boundary of the ischioanal fossa. It is joined by the superior and inferior gemelli outside of the pelvis.

Presentation and Diagnosis

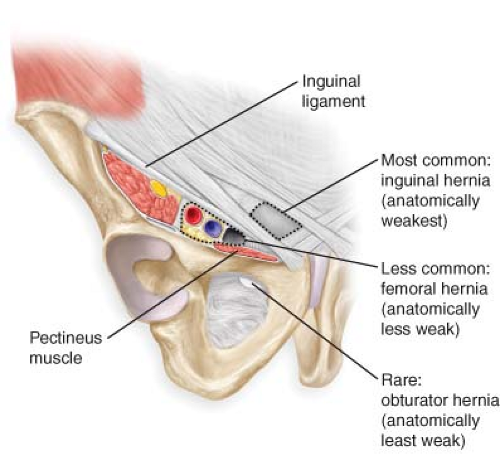

Although much less common than inguinal and femoral hernias (Fig. 10.4), obturator hernias are the most frequent pelvic floor hernias (Fig. 10.5). Obturator hernias represent 0.1% of all hernias. They are small and occur more frequently on the right side. Only 6% are bilateral. Their incidence is 6 times higher in women, especially in middle-aged and elderly individuals. Although the hernia sac usually contains small bowel, hernias encasing omentum, fat, appendix, Meckel’s diverticulum, bladder, ureter, Fallopian tube, focus of endometriosis, and ovary have been reported.

The hernia sac is usually long and narrow within the obturator canal, and expands as it leaves the canal and enters the upper thigh (Figs. 10.6–10.8). Potentially predisposing factors include decreased fat in the obturator canal (usually associated with weight loss), a broad pelvis (commonly found in females) with a larger obturator canal, and progressive laxity of the pelvic floor (frequently due to multiple pregnancies, increased intraabdominal pressure, poor nutrition, and advanced age).

The hernia sac is usually long and narrow within the obturator canal, and expands as it leaves the canal and enters the upper thigh (Figs. 10.6–10.8). Potentially predisposing factors include decreased fat in the obturator canal (usually associated with weight loss), a broad pelvis (commonly found in females) with a larger obturator canal, and progressive laxity of the pelvic floor (frequently due to multiple pregnancies, increased intraabdominal pressure, poor nutrition, and advanced age).

Figure 10.3 A: Obturator canal and the structures within it as seen from within the pelvis. B: Coronal section illustrating the obturator nerve, artery, and vein. C: Obturator nerve. |

There are three anatomically possible types of obturator hernias (Fig. 10.9):

The most frequent type is when the hernia traverses together with the anterior division of the obturator nerve through the external orifice of the obturator canal. In these instances, the hernia is located underneath the pectineus and in front of the external obturator muscles.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree