20

Nutraceuticals as Preventive Medicine in Aging Men’s Health

Case History

Mr. L.K. is a 52-year-old man who was referred to the Optimal Aging Clinic. An internist had previously managed him, but the patient wanted to have a more in-depth evaluation of his health. His concerns were that he felt that he was aging prematurely, and he wanted some directions as to nutrition. He feels that although he eats well and is very watchful over his diet, he may be “nutrient deplete.” Since undergoing plastic surgery, including liposuction and an abdoplasty, he has been watching his weight very carefully. He does report some loss of libido and fatigue. He does not complain of symptoms relating to the lower urinary tract (LUT), but wants to have his prostate checked. Currently, he is on several over-the-counter medications and nutraceuticals including aspirin, vitamin E, vitamin D, omega 3, Osteobiflex, selenium, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and zinc. He also supplements his diet with protein powder, creatine, and glycolide. He asked if he should be on saw palmetto “to protect my prostate from aging.” His father died of complications from Alzheimer’s disease, but also had prostate cancer that was not aggressive. The patient exercises every other day, and does mainly resistance training and each session lasts ∼45 minutes. His diet consists mainly of vegetables, fruits, meat, and very low amounts of processed carbohydrates. Clinical examination reveals a well-sculptured man, blood pressure (BP) 132/80mmHg, and height 5 feet 11 inches. There was a long scar on his abdominal flank. Body fat as measured by electrical impedance was 23.8%, and body fat was 45 pounds. Rectal examination revealed a normal-size prostate with no nodules, and a soft consistency. The patient requested his blood to be sent to a specialized laboratory in Arizona. He wanted assessment for oxidative stress levels (e.g., carotene, peroxides, tocopherols, etc.), age-related hormones (cortisol, estradiol, testosterone etc.), trace metals, and cancer markers including prostate-specific antigen (PSA).

The Rationale for Nutraceuticals

In the United States alone, the business of nutritional supplements increases by millions of dollars each year, with expected sales of $8 billion to $10 billion in 2003.1 The number of products on the shelves of health food stores and pharmacies includes nutraceuticals that were unknown just a few years ago. It is quite evident that many people are taking a more active role in their personal health. Purchases of nutritional supplements reflect that this is taking place. In the past century, there have been major medical victories won over disease states and illnesses that previously were major factors in determining length of life. As a result, the average life span for men born in the 20th century is considerably higher than for those born in the 19th century. As people live longer and causes of death have shifted to more chronic conditions such as coronary artery disease and cancer, the focus of health care has also shifted. It has become more important to consider what is commonly referred to as wellness care, as the public searches for ways to live longer, more active lives.

Chronic conditions that affect the aging population such as diabetes, osteoporosis, and Alzheimer’s disease are being targeted as conditions that people who are knowledgeable, aware, and actively investing in their health can avoid, or, at the very least, minimize their degenerative effects. By the time a man or woman has been diagnosed with osteoporosis, the opportunity for preventive medicine is gone, at least for that condition. And when a man is identified as having prostate cancer, it is often at a late stage of the condition, when therapeutic options are limited. We are learning that there may be hope for many in avoiding Alzheimer’s disease through, at least partially, proper nutrition and supplements. Also in recent years there have been studies suggested that inflammatory processes are instrumental in many of the conditions associated with aging, including cardiovascular diseases. It now appears that many people do not have to face debilitating illness as natural consequences of aging, but, in fact, can enjoy more of their years in a healthy state. We may not necessarily be able to add years to our life, but quite possibly add life to our years. It is in this context that we address the issue of nutritional supplements for men’s health. The advertising that accompanies many products on the market today often overstates or oversimplifies the way a particular product works. We are faced with a vast array of nutraceuticals, products that promise a happier sex life, stronger bones, loss of obesity, and greater physical fitness. Do we need them? Are there real benefits to be gained from them? Or do our normal diets provide all of the nutrition that we need?

Regrettably, for various reasons, our diets in fact do not fully provide all that we need. To mention one factor, we are a people frequently in a hurry, eating on the run or depending on fast-food restaurants to nourish us. So, many of us likely will benefit from taking supplements that will offer us more of the good health that we desire now and for the future. As the interest in nutritional supplements has grown, so has scientific inquiry; although it is sometimes difficult to discern real value from product claims and marketing hype, there are genuine, controlled, objective studies being performed, often with definitive results. The vastness of this topic is such that we choose to be somewhat selective in this chapter, focusing on agents that are available and well known. A major criterion for inclusion in this chapter is that there is good research information available in a scientific publication. For some agents, the data support their use, whereas for others, the conclusion is less positive. We focus on nutritional supplements that address prostrate cancer, LUT symptoms, cardiovascular disease, and sex hormone formation.

Prostate Cancer

With the introduction of PSA testing in the 1980s, the diagnosis of prostate cancer sharply increased. In the United States, it is one of the most common cancers, and is the leading cause of cancer deaths among American men. According to studies, ∼180,000 men in the U.S. develop prostate cancer each year, and 37,000 men die from it each year.2 According to a study published in 2002, prostate cancer is not one disease but a family of diseases that may also include a strong contribution from multiple genetic susceptibility genes.3 Thus it is likely that just as there are various contributing factors, there will be multiple factors in prevention and treatment of prostate cancer. Although genetics and dietary and environmental factors all are important, the role of nutritional supplements has been and continues to be investigated. The agents that have generated the greatest interest include vitamins A, D, and E, the minerals selenium and zinc, lycopene and other carotenoids, and omega-3 fatty acids.

VITAMIN E

Vitamin E is the most commonly used supplement among men with prostate cancer, and it seems to hold promise in both delaying the progression of and in preventing prostate cancer.4 Vitamin E is not a single entity but a group of related compounds including four tocopherols and four tocotrienols. Although the benefits of γ-tocopherol have been studied, the most recently published research indicates that γ-tocopherol is the most natural form of vitamin E, and it has the highest bioactivity. In future studies, it likely to be useful to study these two forms of vitamin E in combination, as both are believed to be significantly active in prostate cancer prevention. There are various properties shown that make vitamin E a possible anti-prostate cancer agent. Perhaps the most important is that, as a potent antioxidant, vitamin E reduces oxidative stress in limiting the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are known to increase oncogene expression. In addition, vitamin E acts as an antiprostaglandin, while increasing the release of arachidonic acid. These two pathways are under greater scrutiny in prostate carcinogenesis.

Vitamin E has been studied in combination with other agents, such as beta carotene and selenium. In a study in which vitamin E alone, beta carotene alone, a combination of the two, and a placebo were given to male smokers, there was no reduction of the incidence of lung cancer.5 But the administration of vitamin E alone did result in fewer cases of prostate cancer than in the other groups.

To date, the largest study on cancer prevention is the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT).6 Begun in 2001, this study will enroll 32,500 men who will be given daily supplements of selenium and vitamin E in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. In this study, which will entail 12 years of research and analysis, patients will take 200 µg of selenium, vitamin E 400mg/day, a combination of 200mg selenium and 400mg vitamin E, or a placebo. The results of this study should provide definitive answers as to the prevention of and/or the halting of progression of prostate cancer.

| Food | mg ATE* |

| Almonds, 1 oz (24 nuts) | 7.4 |

| Hazelnuts, 1 oz (20 nuts) | 4.3 |

| Canola oil, 1 tbsp | 2.9 |

| Broccoli, 1 cup cooked | 2.6 |

| Peanuts, 1 oz (28 nuts) | 2.2 |

| Olive oil, 1 tbsp | 1.7 |

| Wheat germ, 1 tbsp | 1.3 |

| Red bell pepper, 1 cup | 1.0 |

| Kiwifruit, 1 medium | 0.9 |

| Olives, 5 large0.7 | 0.7 |

| Spinach, 1 cup raw | 0.6 |

| Avocado, 1 oz | 0.4 |

| Brown rice, 1 cup | 0.4 |

| Apple, 1 medium | 0.4 |

| Banana, 1 medium | 0.3 |

| Sesame seeds, 1 tbsp | 0.2 |

| Romaine lettuce, 1 cup | 0.2 |

| Beef, ground, 3 oz | 0.2 |

* Currently, the vitamin E nutrient information on reference databases is measured in ATE (α-tocopherol equivalence). Most food companies and the government have not yet updated their information to measure vitamin E in α-tocopherol.

Data from USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 15.

In a recently published study, vitamin E was shown to interfere with the manufacture of both PSA and the androgen receptor.7 Although PSA levels in the study dropped by 80% to 90%, there was also a 25% to 50% reduction in the numbers of cancer cells. The authors report that different types of vitamin E produced different effects, with α-tocopherol succinate being the most effective in halting prostate cancer growth. Table 20–1 lists foods that are rich in vitamin E.

VITAMIN D

In recent years, there have been indications that vitamin D may be useful in both the treatment and prevention of prostate cancer. As far back as 1990, vitamin D deficiency has been suggested as a risk factor for prostate cancer.8,9 Epidemiological studies report that sunlight exposure, which is necessary for the synthesis of vitamin D, is inversely proportional to prostate cancer mortality and prostate cancer is greater in men with lower levels of vitamin D.10 The active form of vitamin D in the body is calcitrol, 1,25-dhydroxy vitamin D. One of the consistent side effects of calcitrol treatment is hypercalcemia.11 More than 200 analogs of vitamin D with modified side chains have been developed to avoid this side effect. Several analogs have been identified as being more effective than the parent compound with little or no hypercalcemia. Several clinical trials are underway with less hypercalcemic analogs along with a study using dexamethasone to offset the toxicity of calcitrol and to allow higher doses (oral doses of 0.5 to 1.5 µLg daily).

VITAMIN A

The value of vitamin A in prostate cancer prevention and treatment is not clear at this time. Levels of vitamin A, chemically known as retinol, have been found to be reduced by five to eight times in prostate cancer tissue compared with normal prostate tissue. A study by Zhang12 reported that vitamin A and its natural and synthetic analogs (retinoids) induce apoptosis in vitro and in animal studies. Newer synthetic retinoids are being studied and may show promise for the future in inducing apoptosis in both hormone-dependent and hormone-independent prostate cancer cell levels. The role of vitamin A, or retinol, is not clearly distinguished from retinoids and carotenoids, although many studies are focusing on the latter group.

LYCOPENE

Lycopene is a carotenoid that is found in tomatoes and other foods and is responsible for the red coloring of these foods. Lycopene is the most prevalent carotenoid in the Western diet, and as a potent antioxidant it is the most significant free radical scavenger in the carotenoid family (which includes beta carotene). One significant difference between beta carotene and lycopene is that beta carotene can be converted to vitamin A, whereas lycopene cannot. In 1995, Giovannucci et al13 conducted a prospective study including 47,894 men that showed an association between lycopene intake and lowered risk of prostate cancer. More recently, it was concluded that the benefit of lycopene might be most pronounced in the protection against more advanced or aggressive prostate cancer.14 The bioavailability of lycopene appears to be dependent on how it is prepared, or altered from the raw tomato. Processed tomato products, such as tomato paste or sauce, have superior lycopene absorption when compared with tomato juice or even raw tomatoes. Absorption appears to be enhanced by processing the tomato with oil, along with the fact that lycopene is released from the fibrous food matrix in preparation. One explanation for the anti-prostate cancer value of lycopene is its ability to inhibit insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), which has been shown to be associated with a greater risk of prostate cancer. Prophylactic doses of lycopene are not yet established, but the usual carotenoid intake is ∼5mg per day. At this time, the ideal intake is not known. One dietary suggestion offered is for men to have at least approximately five servings of tomato products per week. Table 20–2 shows lycopene content in the diet.

| Food | Lycopene Content, mg/100g |

| Tomato, raw | 0.9–4.2 |

| Tomato, cooked | 3.7–4.4 |

| Tomato sauce | 7.3–18.0 |

| Tomato paste | 5.4–55.5 |

| Tomato soup (condensed) | 8.0–10.9 |

| Tomato juice | 5.0–11.6 |

| Ketchup | 9.9–13.4 |

| Watermelon, fresh | 2.3–7.2 |

| Papaya, fresh | 2.0–5.3 |

| Grapefruit, pink/red | 0.2–3.4 |

SELENIUM

Along with vitamin E, selenium is one of the most popular dietary supplements for those seeking to reduce the risk of prostate cancer. In the SELECT trial cited in the section on vitamin E, selenium will be given at a daily dose of 200 mg by itself or in combination with vitamin E, and compared with a placebo group. Studies have shown an inverse relationship between serum selenium and risk of prostate cancer.15 Selenium is believed to exert its preventive effect through the action of glutathione peroxidase, an enzyme that protects the cells from oxidative damage, and is selenium dependent. At this time, results of studies linking selenium to lower incidence of prostate cancer are compelling, and future research will be studied closely. Table 20–3 lists the selenium content of selected foods, and Table 20–4 lists the natural sources of lycopene, vitamin E, selenium, vitamin D, and omega-3 fatty acids.

SOY

The interest in soy as a preventative for prostate cancer comes from epidemiological data showing a lowered incidence among Asian men compared with men in the United States. In Japan, soy is widely consumed, and is believed to possess anticancer properties. The active agents believed responsible for these benefits are the isoflavones genistein and diadzein. American men, by comparison, consume little soy; thus, it has been theorized that their dietary difference is significant in the relative incidence of prostate cancer. However, studies in rats do show that dietary genistein from soy can suppress chemically induced prostate cancer.16 Clearly, the basis for future testing has been established, without an expectation of determining an effective daily or weekly intake of soy protein. Although genistein and diadzein have theorized modes of action, exact mechanisms have not yet been determined.

| Food | Selenium, µg |

| Brazil nuts, ¼ cup | 1036 |

| Oysters, 3.5 oz | 115 |

| Chicken liver 3.5 oz | 71 |

| Raw oyster, 3.5 oz | 70 |

| Steamed clams, 3.5 oz | 64 |

| Beef liver, 3.5 oz | 57 |

| Sardines, 3.5 oz | 46 |

| Crab, 3.5 oz | 40 |

| Whole wheat pasta, 1 cup | 36 |

| White pasta, 1 cup | 30 |

| Wheat germ, ¼ cup | 28 |

| Molasses, blackstrap, 2 tbsp | 25 |

| Sunflower seeds, ¼ cup | 26 |

| Cooked oatmeal, 1 cup | 19 |

| Soy nuts, ½ cup | 17 |

| Freshwater fish, 3.5 oz | 15 |

| Egg, boiled, one | 13 |

| Tofu, ½ cup | 11 |

Courtesy of the Northwestern University Feinburg School of Medicine nutrition web page.

OMEGA-3 FATTY ACID

Fat is the dietary component most frequently associated with prostate cancer.17 Because the association of low-fat diets with a low incidence of prostate cancer is well established, the constituent fatty acids have been the subject of very interesting studies. Particularly under investigation are the essential fatty acids that are unsaturated and are of two types: omega-6 fatty acids from linoleic acid and omega-3 fatty acids, derived from linolenic acid. Linolenic acid is mainly found in fish oils, whereas linoleic acid comes mainly from vegetable seed oils. This interest in the essential fatty acids coincides with research linking cancer to inflammatory events. Although the similarity of their names can be confusing, these two groups have very different activities relative to prostate cancer. For example, although omega-3 fatty acids, docahexanoic acid, and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) inhibit the growth of androgen-unresponsive prostate cancer line, linoleic acid stimulates its growth. The differing effects are believed to be linked, in part, to the manner in which they affect prostaglandin synthesis. Linoleic acid contributes to the formation of the inflammatory prostaglandins, whereas linolenic acid metabolizes the series-3 antiinflammatory prostaglandins (PGE3).

In addition, fatty acids appear to influence sex hormone levels. It is well known that testosterone is converted to the active metabolite dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by the 5α-reductase enzyme. Dihydrotestosterone is believed to be the androgen primarily involved in the progression of prostate cancer. Linolenic acid has been shown by Liang and Liao18 to reduce the activity of 5α-reductase, thus showing another possible mechanism in prostate cancer prevention. There are unanswered questions at this time regarding how to modify the diet and optimize the effects of omega-3 fatty acids. It seems feasible that, at a minimum, men should be encouraged to regularly include fish in their diet, particularly cold-water fish rich in EPA.

ZINC

Zinc is an important mineral in men. Fascinatingly, the concentration of zinc in the prostate is about ten times more than any other body tissue. It has been reported that men with prostate cancer are reported to have low zinc levels. As such, some researchers believe that zinc is essential to prostate function and may even help prevent cancer. Most of the studies have been inferred from in vitro models. Liang et al19 reported in 1999 that zinc inhibits human prostatic carcinoma cell growth, possibly due to induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. There are no large longitudinal human studies demonstrating the protective role of zinc. However, lack of these studies does not prove that it is ineffective. Zinc in modest doses is safe, but it may cause gastrointestinal problems if taken orally in high doses above 50 to 100 mg. To offset this, zinc can be compounded into a gel and applied topically. Some clinicians not only think that zinc is preventive of prostrate cancer, but also advocate treating benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) and chronic prostatitis with this mineral. Zinc is found in abundance in pumpkin seeds, oysters, lean meats, and wheat germ.

Sex Hormone Formation

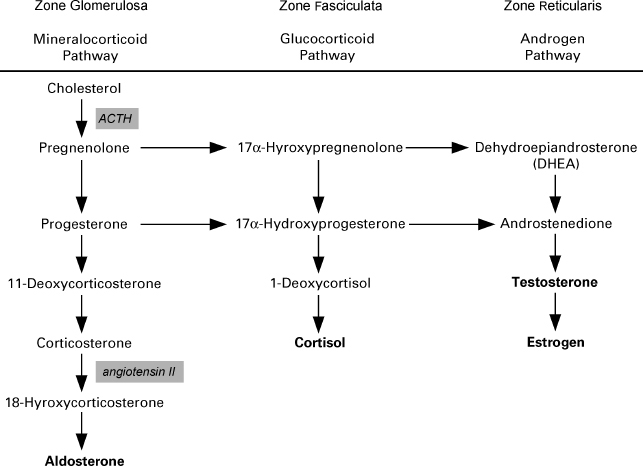

Various nutritional supplements are involved in the steroid cascade of sex hormone formation, such as prohormones (e.g., DHEA), and agents that alter the metabolic pathways (e.g., 5α-reductase inhibitors).

DEHYDROEPIANDROSTERONE

Prohormones are hormones that have some intrinsic value in themselves, but primarily serve as precursors to other, more potent hormones. Perhaps the most commonly used prohormone in the United States is dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), which, at the time of this writing, is available without a prescription. Many countries in the world require a physician’s prescription. Charts of the sex hormone pathways show DHEA as a direct precursor to androstenedione. DHEA is recommended for various purposes, but our major concern here is to show that, as it serves to form androstenedione, it is a vital link in the sex hormone progression.

ANDROSTENEDIONE

Androstenedione is a well-known prohormone, coming into the spotlight through its use by popular professional athletes. Commonly referred to as “andro,” this agent possesses anabolic and androgenic properties of its own; it is mainly considered for use because it is a direct precursor to testosterone. Testosterone is a controlled substance in the U.S., requiring a prescription, but at the time of this writing, androstenedione is available without a prescription. However, tighter restrictions have been suggested for several of these prohormones that would move them to prescription-only status. A major consideration for those taking this supplement is that it not only serves as a direct precursor to testosterone, but also acts in the very same way for estrone, an estrogen with very different properties from testosterone. Therefore, it is likely (and has been reported) that supplements of androstenedione will increase levels of both testosterone and estrone. Oral bioavailability is quite variable, with dosing suggestions ranging from 25 to 500 mg per day. It also has been sold in topical formulations because of perceived greater bioavailability from that dosage form. Studies on androstenedione do not offer conclusive evidence that it is an efficient way to boost testosterone in men. Fig. 20–1 summarizes androgen and pro hormones.

FIGURE 20-1. Pathways of adrenal steroid biosynthesis in the adrenal cortex.

ANDROSTENEDIOL

Androstenediol is chemically the alcohol version of the ketone androstenedione, and possesses virtually the same actions. It serves in the same position in the steroid pathway, that is, it is also a direct precursor to testosterone. Although touted as not having an estrone pathway, several studies have indicated elevated estrone levels after its use. It has also been recommended for use topically, for the same reason as androstenedione. Perhaps in the future, randomized controlled studies will be performed that will offer more definitive answers as to the value of these popular agents.

SAW PALMETTO

Saw palmetto, a naturally occurring plant product from the berries of Serenoa repens, is a very widely used supplement. Pharmacies and health food stores sell millions of dollars of this product each year to men, in the belief that it contributes to their prostate health. One mode of action is that of a 5α-reductase inhibition, thus lowering the amount of testosterone that is converted to dihydrotestosterone. The usual dose is 160 mg of a standardized extract taken twice a day.

NETTLEROOT

Nettle root is also called stinging nettle. The actions of nettle root are believed to be similar to those of saw palmetto, in that it also acts as a 5α-reductase inhibitor. It may have another role in testosterone metabolism, as it is believed to displace testosterone from sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG). In that action, it does not increase the level of total testosterone, but can increase the unbound, free hormone.

FIGURE 20-2. The molecular structure of Chrysin, an inhibitor in the aromatase enzyme system, where testosterone is converted to estradiol. Zone glomerulosa, zone fasciculate, and zone reticularis are different layers of the adrenal cortex. The pathways occur at the different sites.

CHRYSIN

In some men, the conversion of testosterone to estradiol occurs at a greater rate than desired, resulting in estradiol levels that are elevated. Because that process occurs through the aromatase enzyme system, agents have been studied that inhibit that process.19 Chrysin is one such aromatase inhibitor, a naturally occurring flavonoid that has undergone some study with encouraging results (Fig. 20–2). An ideal aromatase inhibitor would both lower estradiol and elevate testosterone levels without toxic side effects. Although the side-effect profile of Chrysin is favorable, so far as is known at this time, the results of studies have not shown conclusive benefits. Oral bioavailability is known to be poor, with daily doses reported from 500 mg to 3 g per day. Some physicians have prescribed Chrysin in a topical application with the expectation of higher blood levels with a lower dose than that of the oral form. At this time, reports are very limited as to the efficacy of Chrysin from either topical or oral administration. Randomized controlled studies are needed to determine the safety, efficacy, and proper dosing for Chrysin.

Saw Palmetto: A Preventive and Therapeutic Nutraceutical for Benign Prostate Hyperplasia and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

One of the most common ailments in aging men involves urinary symptoms such as increased frequency of urination, increased urge, decreased flow rate, and nocturia. Commonly referred to as LUTS (lower urinary tract symptoms), this condition is very similar in effect on men to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), sometimes referred to as benign prostatic obstruction. Although many men report their urinary problems to their physicians as their first response, many others seek out help with nonprescription supplements. By far, the most common supplement that men take for their BPH/LUTS condition is saw palmetto. This herbal plant, known officially as Serenoa repens, is derived from the berry of the American dwarf palm tree. It is, in fact, the most widely used product for voiding problems. Saw palmetto contains various ingredients, such as B-sitosterol, that contribute to its effects. Most studies consider all of the plant’s beneficial effects to be those of saw palmetto, not its component parts.

The primary goal for treating men with BPH is to reduce LUTS and increase quality of life.20 Thus, at this time, clinicians are focused not on eliminating this chronic condition, but to reduce symptoms that lessen quality of life.

What kinds of measures are available to determine whether saw palmetto, or any other agent, can reduce the LUTS incidence in men? There are several, notably the International Prostate Symptoms Score (IPSS), whereby the patients evaluate the occurrence of symptoms such as frequency, urge, incomplete bladder emptying, and nocturia. In addition, urinary flow rate can be measured, along with postvoid residual volume and PSA levels. With these measures in mind, researchers have real parameters by which therapeutic agents can be evaluated and/or compared with others.

Saw palmetto for BPH and LUTS has been the subject of many studies, evaluated separately and also in comparison with finasteride.21,22 In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, saw palmetto led to a statistically significant improvement in urinary symptoms in men with LUTS compared with placebo.23 Another study concluded that saw palmetto caused contraction of prostate epithelia cells and suppression of dihydrotestosterone levels in men with BPH.24 The studies that compared saw palmetto with finasteride have also provided significant evidence of the efficacy of the herbal product. In a widely quoted study by Carraro et al,25 a group of 1089 men were randomized to receive either saw palmetto or finasteride; the results showed almost equal benefit, although less sexual dysfunction was experienced with the herbal product.

The exact mechanisms for all of the benefits of saw palmetto have not been determined. As one action, saw palmetto supplements reduce the tissue levels of dihydrotestosterone. This has led to the belief that there is an inhibition of 5α-reductase involved (5α-reductase is the enzyme system that converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone). Other mechanisms are less clear; although saw palmetto was shown to act as an α1 blocker in in vitro studies,26 it was not shown in in vivo studies.27 From a diagnostic standpoint, it is interesting to note that saw palmetto does not reduce PSA levels, as does finasteride. Because of its reputed 5α-reductase inhibition, some have looked at saw palmetto as a novel agent for treatment of androgenic alopecia. In time, trials may be conducted that can validate this effect. At this time, clinical and/or observational data are scant. In summary, saw palmetto is considered a safe and effective agent for treatment of LUTS as an alternative to finasteride. It is usually dosed orally at 160 mg twice a day.

The Role of Compounding in Nutritional Supplements

From all available information, it is quite clear that there are substantial benefits to be obtained from nutritional supplements. In fact, the evidence is so compelling that it begs the questions: How does one take these agents? Furthermore, how do you find the right doses of the specific nutraceuticals that you are interested in? The authors of this chapter have heard presentations that extol the virtues of so many individual products that it would require a very large inventory as well as a checkoff sheet and schedule to be sure that all desired agents are consumed. To be sure, there are combination commercial products on store shelves for sale now. For example, numerous products are sold for prostate health, perhaps containing selenium, vitamin E, and saw palmetto. These combination commercial products will never fill the needs of all; there has to be a way for an individual, in consultation with his physician and pharmacist, to obtain a preparation that fits his own personal needs. That means that the particular nutraceuticals desired for that person, in the specific optimal dose for each agent, in a dosage form that works well and is compliance-friendly could be made available. It sounds like a lot to ask, but it is a real and present option.

Fortunately, because of the skill and knowledge of a compounding pharmacist, patients can get exactly what they need in a way that works best for them. There are many pharmacists today who have training and expertise in an up-to-date, modernized version of a traditional pharmacy practice. With the availability of top-quality pure powder, granules, or liquid form of the various nutraceuticals in their individual form, knowledge of the art of preparation, and the use of modern equipment and technology, these pharmacists can prepare a product uniquely designed for individual needs. Many of these compounded products can be put in capsules, the most common dosage form. Others can be made into pleasant-tasting, stable oral liquids when that better fits the patient’s needs. And many pharmacists have the expertise and capability required for sterile injections, such as those that are occasionally used for water-soluble vitamins. The future holds the promise of even more convenient dosage forms such as transdermal creams and chewable wafers or treats, as compounding pharmacists seek to fill a void for those with special needs. Although many pharmacies do not have the option of compounding personalized supplements, the number of those that can is steadily growing. In 2003, there were approximately 3000 such pharmacies in the United States.

Discussion of the Case History

Mr. L.K. has requested a consultation to assess his physiological age and to embark on a preventive medicine strategy. He has altered his body fat content substantially through plastic surgery. A DEXA bone densitometry reading was performed to assess his osteoporosis risk. He also requested to be referred for electron beam tomography (EBT) to assess cardiac risk as well. In the clinic, he also underwent a stress electrocardiogram and several blood tests for his vitamin levels, hormonal profile, as well as oxidative stress profiles. His PSA was normal.

Oxidative stress is the harmful state that occurs when there is an overload of free radicals or a decrease in antioxidant levels. Scientific studies have revealed that free radicals are indeed culprits of many diseases of aging, including neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Oxidative stress can also affect conditions affecting vision such as cataracts and macular degeneration. Strategies aimed at limiting and repairing the damage attributed to oxidative stress may slow the advance of numerous age-related diseases. After the assessments, it was discovered that the patient’s cardiac health was good. He further consulted an exercise physiologist and nutritionist to complete his optimal aging screening program. He continued with his current nutritional supplements and compounded testosterone was added, as he was found to be hypogonadal.

Conclusion and Key Points

Most physicians receive little education about nutrition. Although nutrition may influence health and be useful for prevention, the trials that verify the use of nutraceuticals are generally smaller than those verifying medications. There is sometimes a fine line between medications and over-the-counter nutraceuticals, and physicians should be cognizant of what their patients are consuming. Some of these nutraceuticals can interact with medications, and it is prudent for physicians to monitor for side effects. As nutraceuticals is such a large industry, and compounded by multilayer marketing approaches, it impacts the health of millions of people. Some of the nutraceuticals have been evaluated more thoroughly than others. Policy making also decides which nutraceutical may be available to the consumer directly. For instance, DHEA is available over the counter in the United Sates but not in many other countries.

• Prostate cancer seems to be more common in certain races and regions, and scientists have postulated links and possible preventive and even therapeutic interventions.

• So far, vitamin E, vitamin D, vitamin A, lycopene, selenium, soy, omega-3 fatty acid, and zinc have been implicated in preventive roles, but the evidence is not conclusive.

• Certain nutraceuticals may influence androgen metabolism, and of these DHEA, androstenedione, androstenedione, saw palmetto, nettle root, Chrysin, and zinc have been implicated.

• Saw palmetto has been studied quite extensively in the treatment of BPH and LUTS.

• Nutraceuticals can be compounded to alter bioavailability and be specifically useful for some patients.

REFERENCES

1. Business Communications Company, March 11, 2003. www.bccresearch.com/editors/RGA

2. Yip I, Heber D, Aronson W. Nutrition and prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am 1999;26:403–411

3. Miller EC, Giovannucci E, Erdman JW, Bahnson R, Schwartz SJ, Clinton SK. Tomato products, lycopene, and prostate cancer risk. Urol Clin North Am 2002;29:83–93

4. Fleshner NE. Vitamin E and prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am 2002;29:107–113

5. The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. N Engl J Med 1994;330:1029–1035

6. Moyad MA. Selenium and vitamin E supplements for prostate cancer: evidence or embellishment? Urology 2002;59:9–19

7. Zhang Y, Ni J, Messing EM, Chang E, Yang C, Yeh S. Vitamin E succinate inhibits the function of androgen receptor and the expression of prostate-specific antigen in prostate cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:7408–7413

8. Schwartz GC, Hulka BS. Is Vitamin D deficiency a risk factor for prostate cancer? Anticancer Res 1990;10:1307–1311

9. Polek TC. Wiegel Nl. Vitamin D and prostate cancer. J Androl 2002;23:9–17

10. Bodiwala D, Luscombe CJ, Liu S, et al. Prostate cancer risk and exposure to ultraviolet radiation: further support for the protective effect of sunlight. Cancer Lett 2003;192:145–149

11. Konety BR, Getzenberg RH. Vitamin D and prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am 2002;29:95–106

12. Zhang XK. Vitamin A and apoptosis in prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2002;9:87–102

13. Giovannucci E, Aschero A, Rim EB, et al. Intake of carotenoids and retinal in relation to prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:1767–1776

14. Miller EC, Giovannucci E, et al. Tomato products, lycopene, and prostate cancer risk. Urol Clin North Am 2002;29:83–93.

15. Vogt TM, Ziegler RG, Granbard BI, et al. Serum selenium and risk of prostate cancer in U.S. blacks and whites. Int J Cancer 2003;103:664–670

16. Wang J, Eltoum JE, Lamartiniere CA. Dietary genisten suppresses chemically induced prostate cancer in Lobound-Wistar rats. Cancer Lett 2002;186:11–18

17. Kushi L, Giovannucci E. Dietary fat and cancer. Am J Med 2002;113:63S–70S

18. Liang T, Liao S. Inhibition of steroid 5 alpha reductase by specific aliphate unsaturated fatty acids. Biochem J 1992;285:557–562

19. Liang JY, Liu YY, Zou J, Franklin RB, Costello LC, Feng P. Inhibitory effect of zinc on human prostatic carcinoma cell growth. Prostate 1999;40:200–207

20. Jeong HJ, Shin YG, Kim IH, et al. Inhibition of aromatase activity by flavinoids. Arch Pharm Res 1999;22:309–312

21. Coleman CI, Hebert JH, Reddy P. The effect of phytosterols on quality of life in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Pharmacotherapy 2002;22:1426–1432

22. Berges RR, Kassen A, Senge T. Treatment of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia with beta-sitosterol: an 18-month follow-up. BJU Int 2000;85:842–846

23. Gerber GS, Kuznetsov D, Johnson BC, Burstein JD. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of saw palmetto in men with lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology 2001;58:960–964

24. Veltri RW, Marks LS, Miller C, et al. Saw Palmetto alters nuclear measurements reflecting DNA content in men with symptomatic BPH: evidence for a possible molecular mechanism. Urology 2002;60:617–622

25. Carraro JC, Raynaud JP, Koch G, et al. Comparison of phytotherapy (Permixon) with finasteride in the treatment of benign prostate hyperplasia: a randomized international study of 1,098 patients. Prostate 1996;29:231–240

26. Goepel M, Hecker U, Krege S, et al. Saw palmetto extracts potently and noncompetitively inhibit human alpha1-adreno-ceptors in vitro. Prostate 1999;38:208–215

27. Goepel M, Dinh L, Mitchell A, et al. Do saw palmetto extracts block human alpha1-adrenoceptor subtypes in vivo? Prostate 2001;46:226–232

< div class='tao-gold-member'>