Reactive Urothelial Atypia

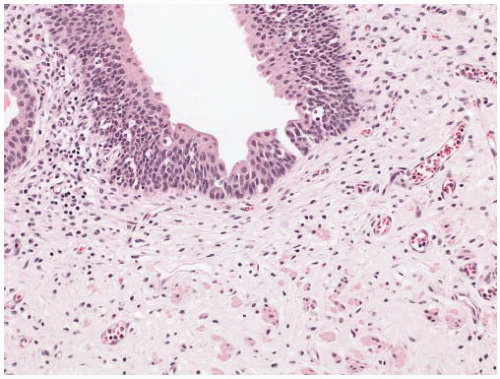

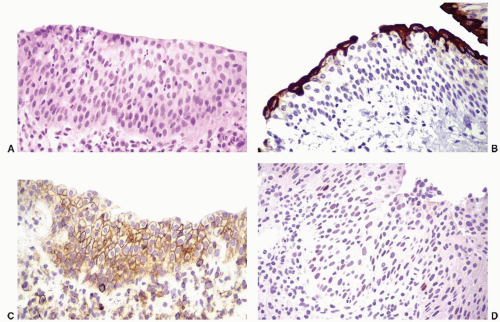

Reactive urothelial changes, sometimes florid, may be associated with instrumentation, indwelling catheters, and any inflammatory condition. Morphologically, the reactive urothelial cells may show some degree of nucleomegaly and hyperchromasia, but the overall architecture of the urothelial cells (i.e., even spacing and alignment perpendicular to the basement membrane) is generally maintained. Intercellular edema may be conspicuous, and an associated intraurothelial inflammatory infiltrate is common.

7,

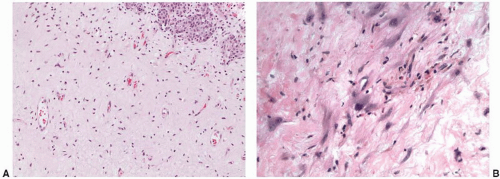

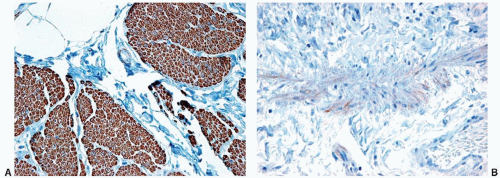

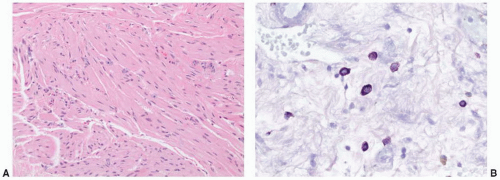

64 Despite the prominence of one or multiple nucleoli and increased mitotic activity (which may be striking), the chromatin remains finely dispersed throughout the nucleus (

Fig. 5-12A and B). These nuclear changes suggest urothelial carcinoma in situ (CIS), but the nuclear pleomorphism, irregular distribution of nuclear chromatin (i.e., striking nuclear hyperchromasia), and the loss of orderly alignment of the individual cells in CIS are distinctive (

Table 5-2). The use of adjunctive immunohistochemistry to aid in this distinction has been studied, and a panel of antibodies to cytokeratin 20, p53, and standard isoform CD44 may be useful in some settings (

Fig. 5-13).

64 CIS shows strong diffuse cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for CK20 in approximately 80% of cases, while diffuse nuclear p53 reactivity is seen in up to 57%. CD44s expression is either limited to the basal layer or absent in CIS. In contrast, reactive atypia is characterized by full-thickness membranous reactivity for CD44s with CK20 expression limited to superficial umbrella cells. p53 may show patchy nuclear staining in benign and reactive urothelium, but it does not have the intensity or the diffuse immunoreactivity pattern typical of CIS. Reactive urothelial atypia due to radiation and chemotherapy is discussed in detail below (see

Box 5-1).

Papillary-Polypoid Cystitis

Papillary/polypoid cystitis is a clinically benign pattern of urothelial injury often secondary to an indwelling catheter or vesical fistula, but of diverse potential etiologies.

65,

66,

67,

68,

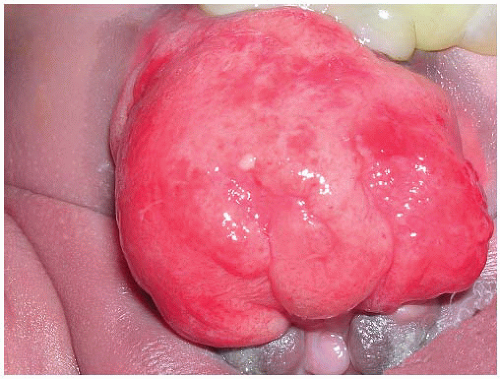

69 This lesion affects a broad age range, but the mean patient age is 49 years, and the majority of patients are male. It is relatively rare, but polypoid cystitis may be seen in up to 80% of the patients with an indwelling catheter. It may also be seen after radiation therapy. Although usually of microscopic size, grossly visible polypoid lesions may be seen. The entire bladder may be involved when a catheter has been present for a prolonged period of time, usually 6 months or more. With vesical fistula, extravesical symptoms may be initially absent in approximately half the cases, making diagnosis difficult. The cystoscopic appearance may also closely mimic a neoplasm.

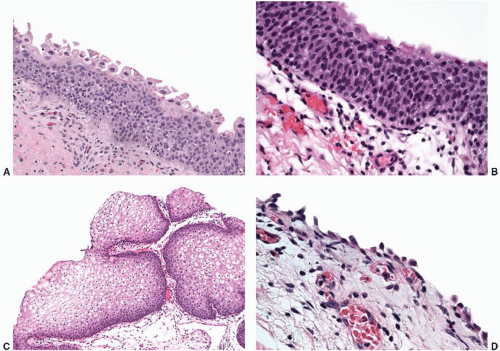

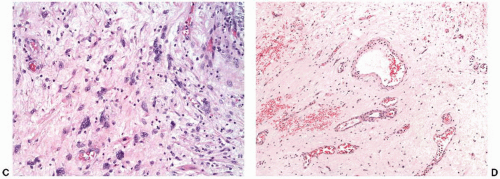

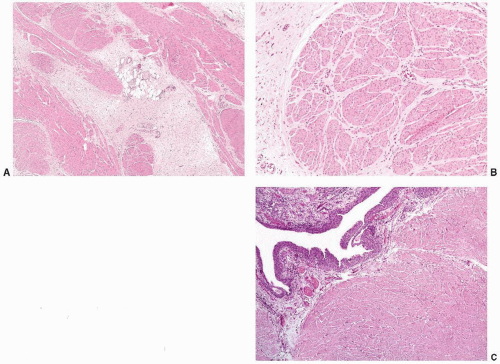

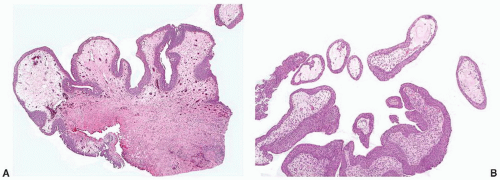

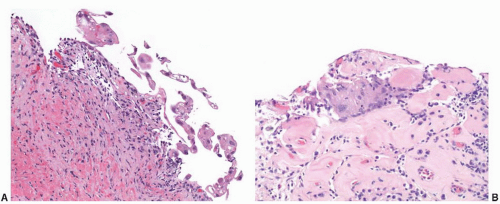

Morphologically, the papillary and polypoid patterns may be intermixed, but lesions with relatively slender, nonbranching exophytic projections are termed papillary cystitis, while broad-based, edematous lesions have been termed polypoid cystitis (

Fig. 5-14A and B). Characteristically, the exophytic appearance results from edema in the lamina propria, but variable fibrosis, chronic inflammation, and associated dilated blood vessels are also present. These lesions exist along a morphologic continuum with bullous cystitis depending on the degree of edema; some authors have used the following convention: Lesions that are taller than they are wide are termed papillary/polypoid cystitis and vice versa for bullous cystitis. Older lesions tend to have less edema with more stromal fibrosis. As papillary and polypoid cystitis are usually associated with inflammation, there may be metaplastic changes in the lesional or adjacent urothelium. In both types of cystitis, the urothelium may be hyperplastic and reactive appearing, but usually is not as stratified as in a neoplasm. Some authors have suggested that the lesion described as “fibroepithelial polyp” of the bladder has many similar histologic features and may represent an end-stage phase of papillary-polypoid cystitis.

The main diagnostic consideration is a low-grade papillary urothelial neoplasm, particularly urothelial papilloma or papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential. In

some cases, usually with recent catheterization, papillary/polypoid cystitis shows marked reactive epithelial changes with small, prominent nucleoli, urothelial hyperplasia, and mitotic activity mimicking a high-grade lesion.

70 In general, papillomas have more slender papillae; the papillae of papillary cystitis often have a bulbous tip with prominent stromal edema. In addition, urothelial papillomas have other features that, at least in aggregate, may aid in the distinction when present: a very prominent umbrella cell layer or marked cytoplasmic vacuolization, a gland-in-gland pattern within the papillae, a dilated lymphatic space filling the papillae, a more complex papillary pattern with secondary and tertiary branching, and an admixed endophytic (inverted) component.

71,

72 Significant cytologic atypia within a papillary lesion or the adjacent urothelium favors a diagnosis of neoplasia.

Follicular Cystitis

Follicular cystitis, which is also called cystitis follicularis or lymphofollicular cystitis, is reportedly more prevalent in children, but occurs across a wide age range and may have multiple etiologies.

74,

75,

76 It is often associated with repeated bacterial urinary tract infections and factors that contribute to prolonged infection such as paraplegia and indwelling catheters.

77 Other associations include carcinomas of the urinary bladder (with sterile urine), intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) or interferon therapy, and

Salmonella infection.

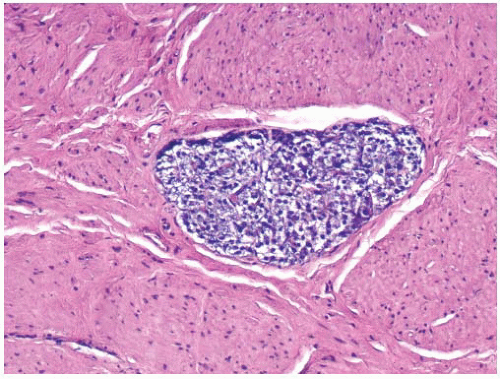

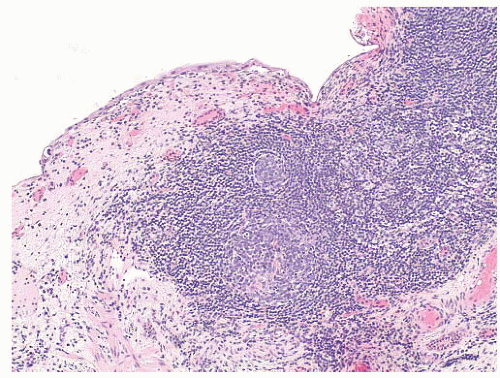

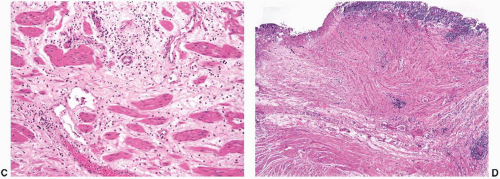

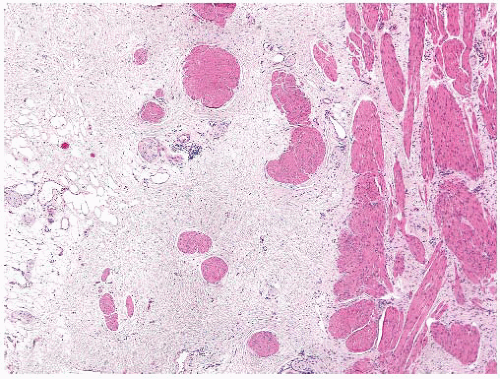

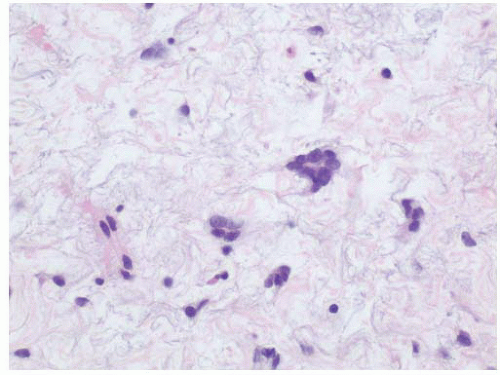

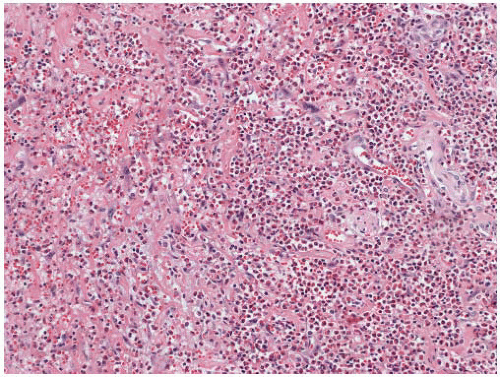

78 Grossly, the urothelial mucosa is edematous with small pale to white nodules. Microscopically, the nodules are composed of lymphoid follicles in the lamina propria with or without germinal center formation (

Fig. 5-16). When due to infection, the lymphoid follicles often disappear when abacteriuria is achieved.

74 Although rare, the main differential diagnosis is a low-grade malignant lymphoma, such as follicular lymphoma, involving the urinary bladder. Lymphoma may be excluded by a routine immunohistochemistry evaluation to distinguish reactive lymphoid from neoplastic proliferations.

79,

80 Clinically, the nodular lesions seen on cystoscopy may mimic other infections such as tuberculosis, but the absence of granulomatous inflammation excludes that possibility.

Painful Bladder Syndrome or Interstitial Cystitis

Interstitial cystitis, now commonly referred to as “painful bladder syndrome,” is a poorly defined chronic inflammatory process of unknown etiology that affects the urinary bladder.

81,

82,

83 The clinical symptoms include urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia, suprapubic pressure, and pain with either bladder distention or voiding. By definition, patients experience the clinical urinary symptoms despite sterile urine cultures by routine laboratory techniques. Urodynamic studies typically reveal decreased bladder filling capacity. Prior therapies with

known bladder irritants, concomitant urothelial neoplasia, and infections would exclude the diagnosis of interstitial cystitis.

81 The American Urologic Association guidelines have provided the following modified definition: “An unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure, discomfort) perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than 6 weeks duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes.”

83The reported incidence of painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis varies widely, ranging from 10 to 510 per 100,000. This variation is likely due to the varied criteria that have been utilized for diagnosis between different studies. Despite being described almost 100 years ago, the disease remains a clinical and therapeutic enigma. Some research has suggested the possibility of an autoimmune disorder, but there is no general agreement about the pathophysiology of the disease.

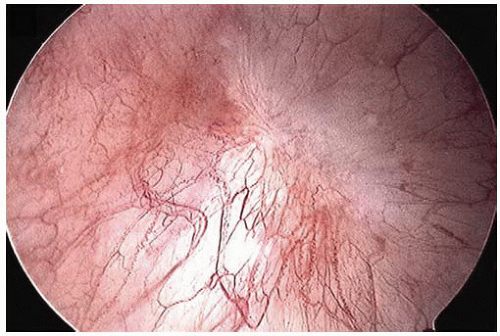

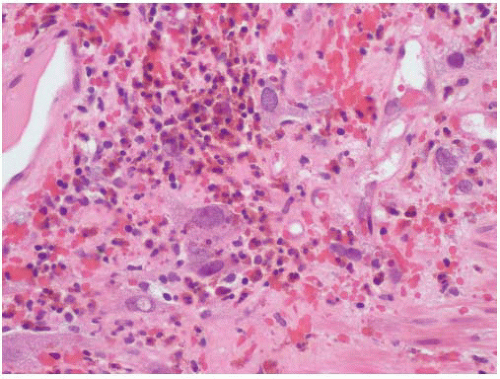

Cystoscopic evaluation of the disease may be categorized as “nonulcer or early disease” and the classic type. The nonulcer disease is characterized by normal mucosa at initial evaluation with the development of small submucosal hemorrhagic foci, called glomerulations, and linear cracks during/after distention (

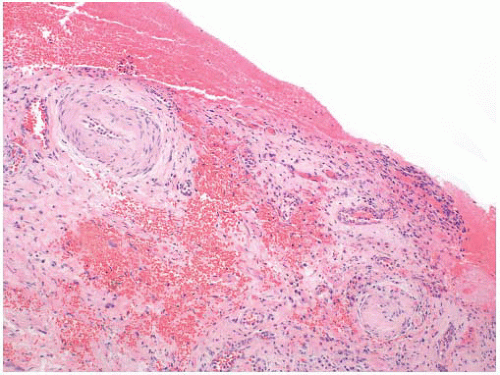

Fig. 5-17). In the classic pattern, there are single or multiple patches of reddened mucosa with small blood vessels radiating from a central mucosal scar. Classically, the mucosa ruptures under hydrodistention creating oozing of blood, which is the prototypical Hunner ulcer. In well-developed cases, the entire wall may be fibrotic and contracted. The trigone, in general, is not involved.

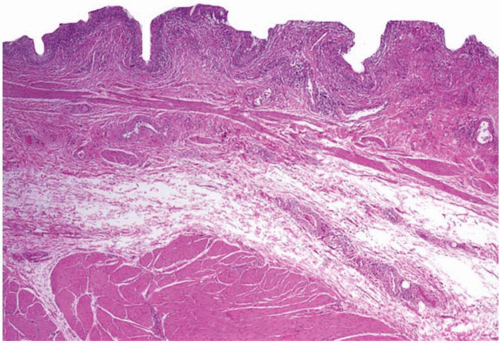

The role of morphology in the diagnosis of interstitial cystitis remains controversial. In our opinion, the role of the surgical pathologist is twofold: (a) most importantly, to exclude other specific forms of cystitis and urothelial CIS and (b) to detail histologic features for correlation with cystoscopy. There are no pathognomonic histologic features of interstitial cystitis, but common findings include ulceration with variably admixed fibrin, erythrocytes, and inflammatory cells, especially neutrophils. Associated granulation tissue and perineural lymphocytic infiltrates are common, and urothelial denudation is frequent. Ulcers typically extend deep into the lamina propria with surrounding edema and congestion. In patients without ulcers, the morphologic changes may be subtle and include suburothelial hemorrhage, edema, and possibly mucosal tears (

Fig. 5-18). In long-standing disease, fibrosis of the muscularis propria may be present. There is considerable debate regarding the utility (i.e., specificity) of mast cell counts in the distinction from other inflammatory processes. However, there are reports of increased intravesical mast cell infiltrates in patients with interstitial cystitis (

Fig. 5-19A and B).

84,

85,

86 One of the major roles of biopsy evaluation is to exclude other lesions in the clinical differential diagnosis, particularly urothelial CIS. When the urothelium is extensively denuded, additional levels may be necessary to exclude this possibility. Since the morphologic features are not entirely specific, the final diagnosis of interstitial cystitis requires close clinical (i.e., history, cystoscopy, and voiding studies) and pathologic correlation.

A recent review of patient management identified >180 published treatment modalities.

82 These modalities include variations of behavioral, dietary, pharmacologic, and surgical interventions. There is general agreement on the use of some oral and intravesical agents, such as amitriptyline, hydroxyzine, and pentosan polysulfate sodium; however, there is a lack of definitive conclusions regarding optimal therapy.

Radiation and Chemotherapy Cystitis

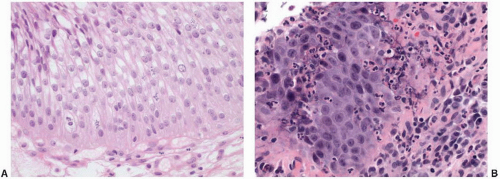

In radiation or chemotherapy cystitis, patients often present with hematuria or voiding symptoms. Biopsy evaluation of the urothelium may show striking cytologic atypia.

73 Cytoplasmic and nuclear vacuolation, karyorrhexis, and a normal nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio are features suggestive of radiation injury (

Fig. 5-20A and B). In general, robust mitotic activity is absent. These histologic and clinical changes are both time and dose dependent; however, histologic changes may be seen for years. In addition, the

toxicity may be potentiated by concomitant therapy with cyclophosphamide. Radiation-induced histologic changes are similar to those seen with intravesical chemotherapy, but with intravesical chemotherapy the histologic changes are often more restricted to the superficial urothelial cell layer. Atypical mesenchymal cells similar to those seen in giantcell cystitis are also typically present in the lamina propria (

Fig. 5-21). Other characteristic changes of radiation injury including marked stromal edema or fibrosis; prominent telangiectatic change, hyalinization, and thrombosis of the vessels are also helpful. Pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia of the epithelium (discussed later) may be striking.

In the posttherapy setting, one should have a high threshold for the diagnosis of urothelial CIS. In difficult cases with uncertainty as to the appropriate diagnosis, use of the diagnostic term “atypia of unknown significance” is warranted. This allows repeat cystoscopy and biopsy evaluation after inflammation resides and avoids the potential overdiagnosis of reactive urothelial neoplasia.

Marked urothelial changes may be seen following radiation or chemotherapy. In general, radiation atypia is characterized by changes in the umbrella cell layer that include cytoplasmic vacuolization, nucleomegaly, and multinucleation. A reactive immunophenotype is maintained in reactive urothelial changes secondary to radiation therapy.

87 Intravesical chemotherapy with agents such as mitomycin may also cause marked epithelial atypia. There are very little data available in the diagnostic pathology literature on the specific urothelial alterations after intravesical chemotherapy,

88 but in our experience the cytoplasm of the urothelial cells becomes more

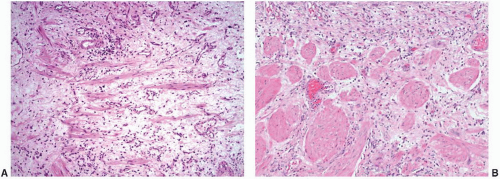

uniformly eosinophilic, and nuclear changes similar to those seen with radiation are common (

Fig. 5-22A and B).

Hemorrhagic Cystitis

Hemorrhagic cystitis is caused predominantly by chemotherapeutic agents, most commonly cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and radiation therapy,

89 but viral etiologies are also well described (see “

Viral Cystitis”). Less common causes include other chemotherapeutic agents such as busulfan and thiotepa, aniline and toluidine derivatives used in dyes and insecticides, and many other compounds.

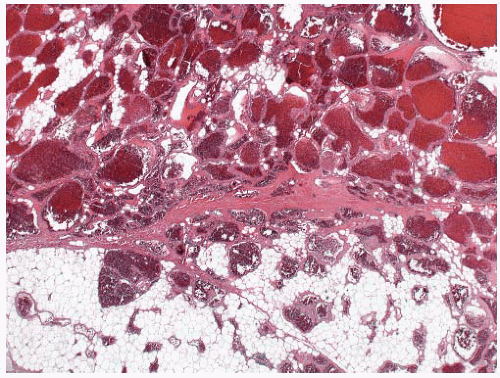

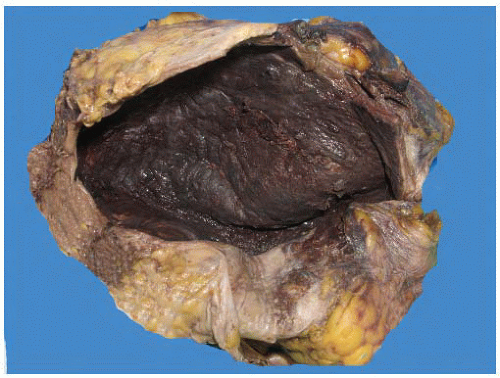

90 The clinical presentation is typically onset of severe hematuria shortly after exposure to the inciting agent (

Fig. 5-23). Morphologically, hemorrhagic cystitis is characterized by extensive hemorrhage into the lamina propria with vascular congestion and edema. The overlying epithelium may show striking nuclear atypia similar to that seen in association with radiation or intravesical chemotherapy.

Eosinophilic Cystitis

“Eosinophilic cystitis” is a descriptive term that has been applied to mixed inflammatory infiltrates of the lamina propria rich in eosinophils (

Fig. 5-19).

91,

92 This type of inflammatory infiltrate is seen in a broad age range, but approximately 20% of cases occur in children. There is an equal sex distribution. Patients often present with dysuria, frequency, hematuria, and/or flank pain. Rarely, patients can present with an infiltrative mass lesion that may induce urinary obstruction. On cystoscopy, the lesions often have a polypoid appearance that may mimic polypoid cystitis or urothelial carcinoma in adults or a botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma in children.

Eosinophilic cystitis is best regarded as a pattern of inflammation associated with a variety of causes and not a single diagnostic entity; however, there are two general settings: (a) allergy related and (b) injury related. Bladder eosinophilia has been reported in association with allergic gastroenteritis, asthma, or other allergic disorders, especially in women and children.

91 This likely represents a systemic eosinophilic process that is distinct from the other nonspecific infiltrates. In adults, most commonly older males, eosinophilic infiltrates are more frequently associated with bladder injury from underlying prostatic hyperplasia, bladder carcinoma, or prior biopsy. Rarely, eosinophilic cystitis may be seen secondary to a parasitic infection.

93 The word “eosinophilic” occasionally causes some confusion with neoplastic entities in children and

young adults; however, it should be emphasized that there is no relationship to Langerhans cell histiocytosis (previously called eosinophilic granuloma).

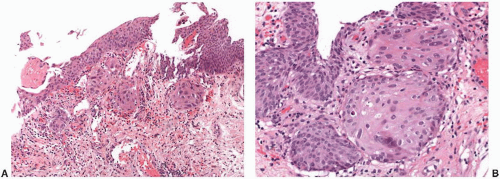

Histologically, early lesions of eosinophilic cystitis are characterized by inflammatory infiltrates rich in eosinophils (

Fig. 5-24). In some cases with extensive infiltrates, necrosis of the muscularis propria may be seen. As lesions mature, the eosinophilic infiltrate becomes less prominent with an admixture of mature lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Patient management depends on the clinical setting. With allergy-associated lesions, removal of the inciting agent may alleviate the symptoms in the bladder. In idiopathic cases, a course of antihistamines and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are often tried. Other intravesical therapies, such as mitomycin C, dimethylsulfoxide, cyclosporine A, and oral corticosteroids, have also been utilized. In severe cases with unremitting symptoms, transurethral surgical resection and rarely cystectomy may be required.

Nonspecific Acute and Chronic Cystitis

In some patients with symptomatic inflammatory conditions of the urinary bladder, no identifiable etiology is determined after workup for an infectious etiology, and the patients do not have clinical features of interstitial cystitis. When biopsied, nonspecific histologic changes may be seen. Recent changes may include edema, hyperemia, neutrophilic infiltrate, and histiocytes. Surface ulceration as well as associated reactive urothelial atypia may also be present. Chronic changes include fibrosis and mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrates.

Encrusted Cystitis

Encrusted cystitis refers to the deposition of inorganic salts in the bladder mucosa and is caused by urea-splitting bacteria that alkalinize the urine.

97,

98,

99 It is most common in women, and presenting symptoms are similar to other urinary tract infections. Cystoscopically, the lesions may be diffuse and have a gritty appearance. Morphologically, encrusted cystitis is characterized by a fibrinous exudate with admixed calcified, necrotic debris and inflammatory infiltrates (

Fig. 5-25A and B). The main differential consideration is urothelial carcinoma associated calcification, which may be seen in areas of necrosis or prior biopsy/resection.

100 Accordingly, in a limited sample the carcinoma may be missed, and careful correlation with the cystoscopic impression is important to avoid a delay in diagnosis.