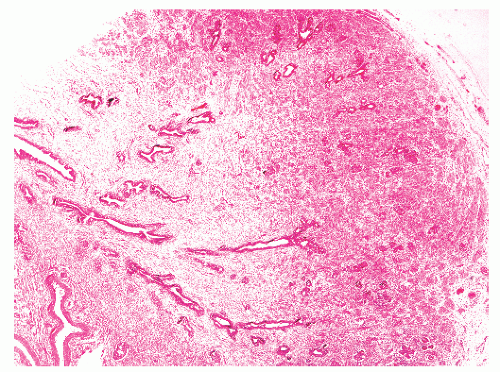

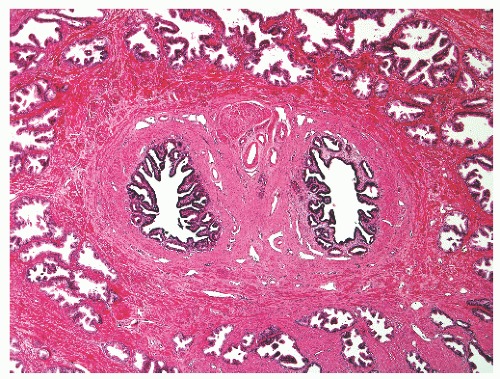

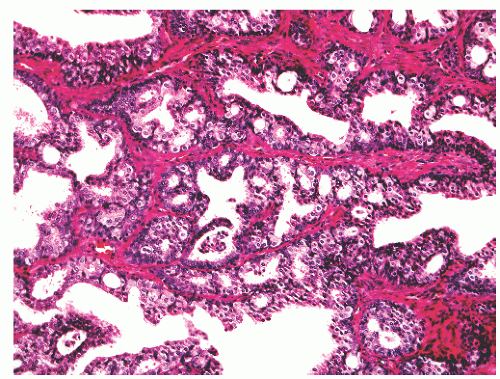

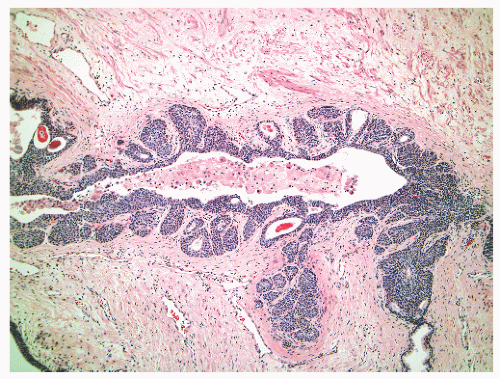

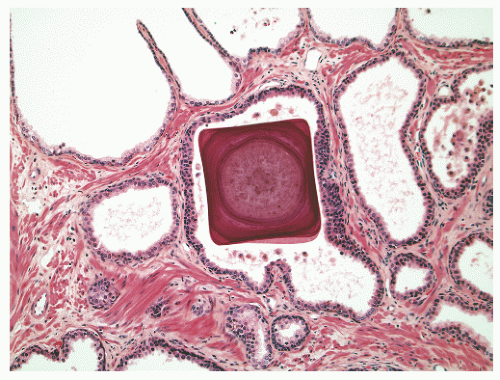

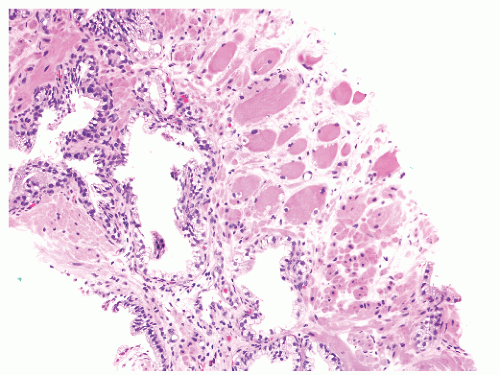

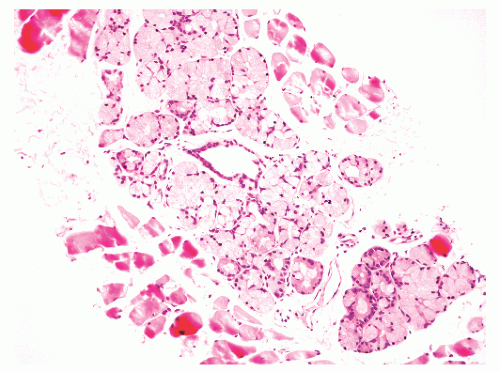

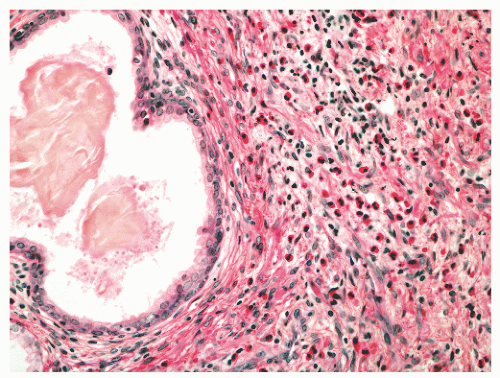

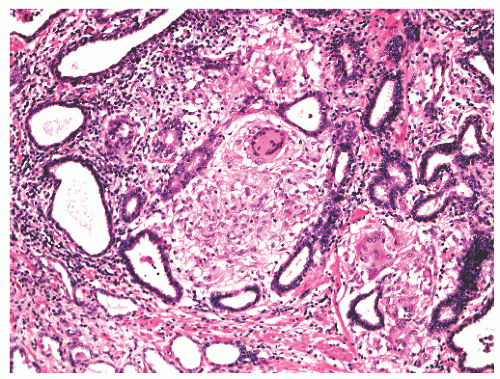

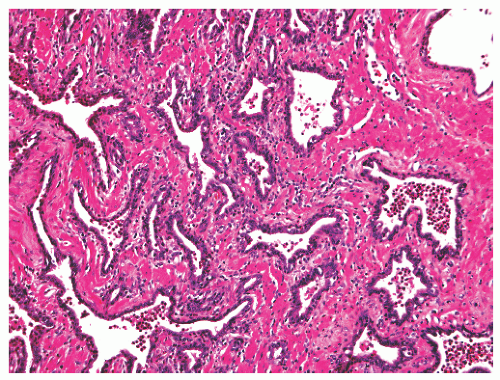

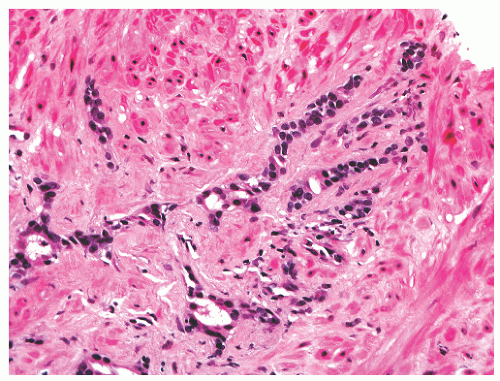

into smooth muscle cells that closely surround the epithelial ducts. This dynamic dance of tissue remodeling entails coordinated temporal and spatial processes of ductal budding, branching morphogenesis, cellular proliferation, and secretory function.13 By 13 weeks some 70 primary ducts are present. Three stages of development from 20 weeks’ gestation to 1 month of age have been delineated.14 The bud stage at 20 to 30 weeks’ gestation exhibits solid cellular buds at the end of ducts, with spindled cells in the center and columnar cells at the periphery. The bud-tubule stage at 31 to 36 weeks shows small collections of cellular buds and acinar structures (Figs. 8-1 and 8-2). The third stage is characterized by more distinct lobular organization of acinotubular clusters. Squamous metaplasia of prostatic ducts and urethra is a common finding in the fetal prostate. This metaplasia is gradually lost after birth.

Table 8-1 ▪ PSEUDONEOPLASMS OF THE PROSTATE | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

12 to 18 years of age there is a pubertal maturation period with a significant increase in gland size, to 11 to 18 g by age 18. This period is characterized by androgen-driven gland branching, and differentiation of immature prostatic epithelium into adult-type basal and secretory cells.

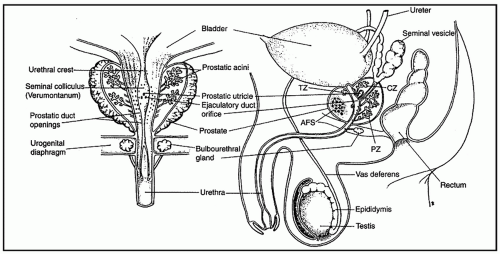

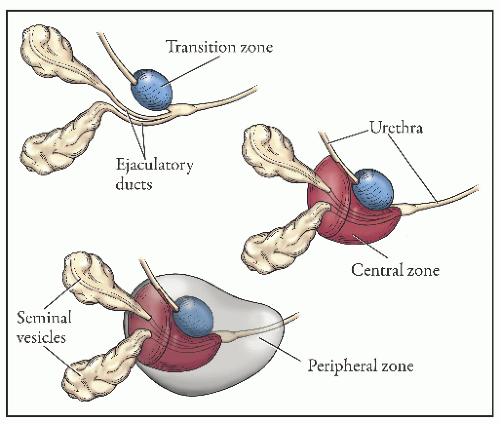

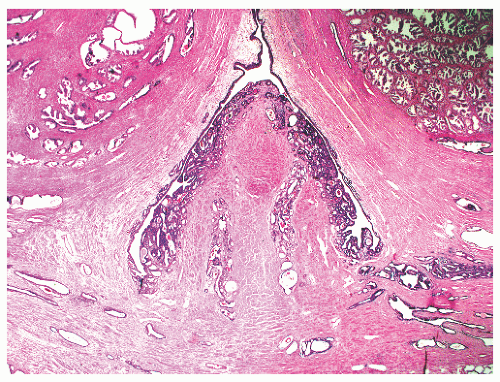

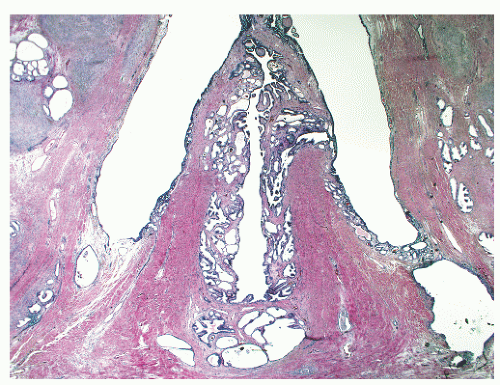

the proximal urethra (Fig. 8-4). The main ducts of this zone drain into posterolateral recesses of the urethra at a point just proximal to the urethral angle. Some of the more medial ducts penetrate through the thick smooth muscle bundles of preprostatic sphincter. Also found in the smooth muscle of the preprostatic sphincter are minute ducts and abortive acinar arrangements of periurethral glands, which constitute only about 1% of the total glandular volume of the prostate. The central zone makes up about 25% of the entire prostate gland and is a posteriorly situated cone-like structure with the base of the cone projecting toward the base of the bladder. The paired ejaculatory ducts (Fig. 8-5) run through the central zone from the seminal vesicles to their exit at the posterior urethral protuberance, known as the verumontanum (or colliculus seminalis) (Fig. 8-6). Within the verumontanum is a cul-de-sac, the prostatic utricle, located between the ejaculatory ducts (Fig. 8-7). It may also lie deep to the ejaculatory ducts or may be embedded as a tiny cavity in the prostatic parenchyma.22 The ducts from the central zone drain into the urethra via orifices positioned just next to the ejaculatory duct orifices on the verumontanum. The peripheral zone of the prostate gland is the bulk of the posterior, lateral, and apical portion of the prostate gland and accounts for 70% of the total gland volume. The ducts of this zone empty into the posterior urethral recesses or grooves in a double row from the verumontanum to the prostatic apex. Finally, a patch of nonglandular tissue called the anterior fibromuscular stroma is present anteriorly over the prostate and extends from the bladder neck to the apex of the prostate.

Table 8-2 ▪ COMPARISON OF THE THREE ZONES OF THE PROSTATE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

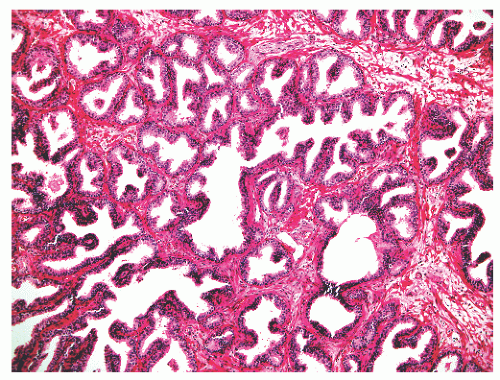

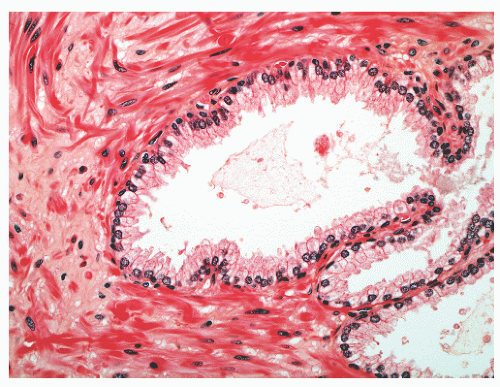

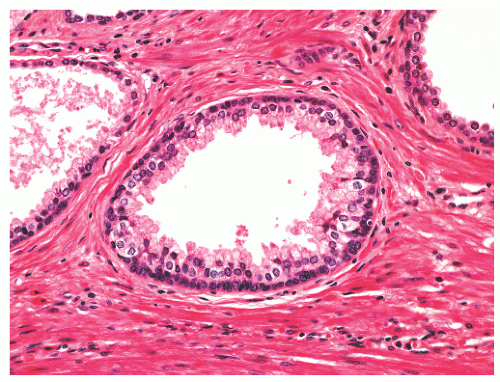

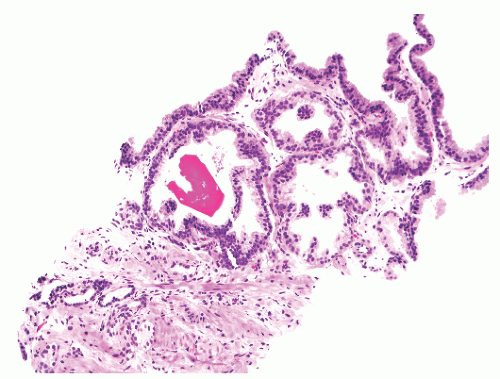

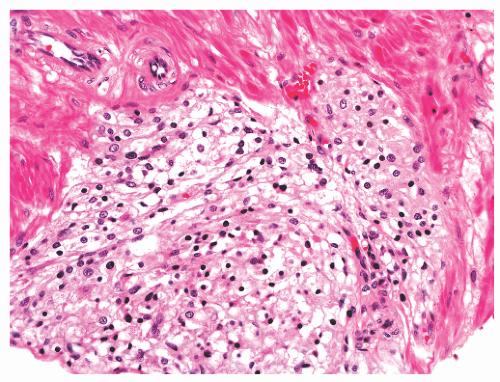

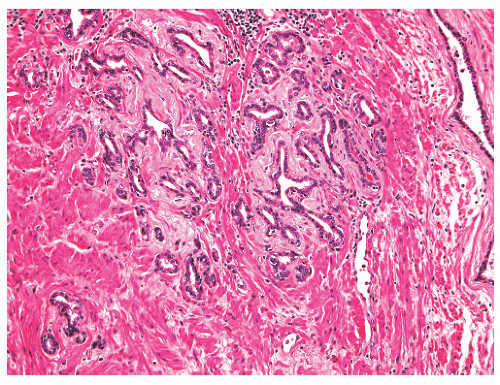

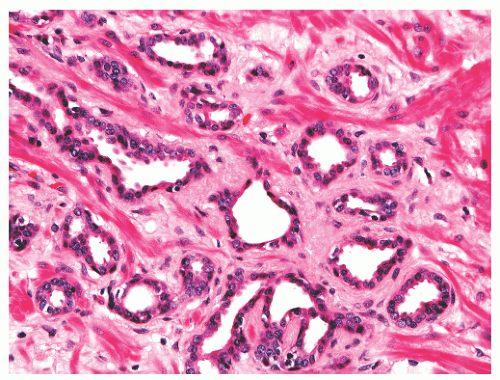

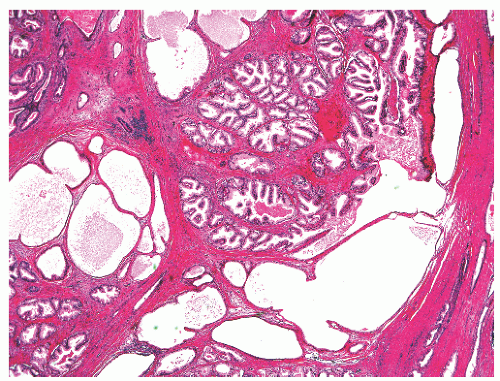

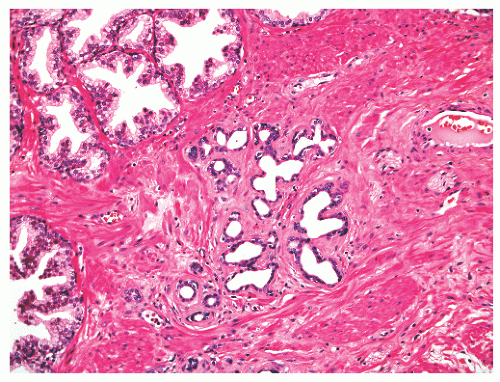

with 1:1 for the peripheral and transition zones. Also, central zone glands are larger and display intraluminal projections with fibrovascular cores. Central zone epithelium displays tall columnar cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, a prominent basal cell layer, and on occasion complex intraluminal architecture such as Roman bridge and cribriform formations (Fig. 8-9). These findings can be misdiagnosed as atypia or prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN).23 Central zone epithelium is distinctive in its selective expression of pepsinogen II, lactoferrin, and lectin-binding sites.7 Central zone epithelium also differs from epithelium in other zones in proteomic profile.24

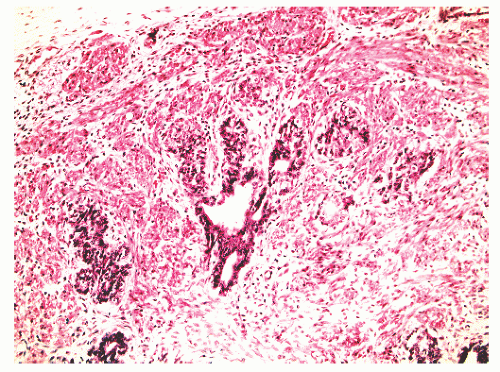

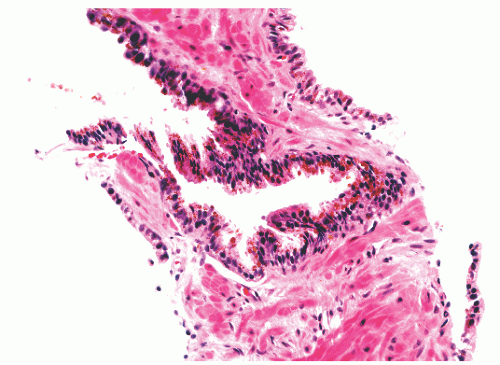

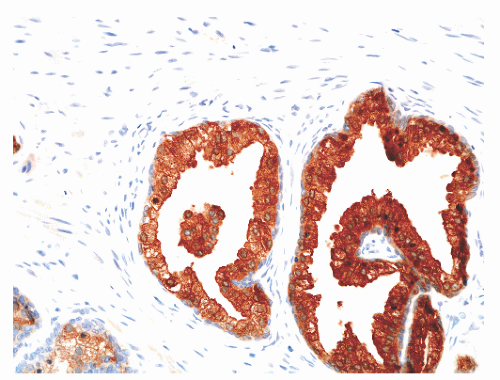

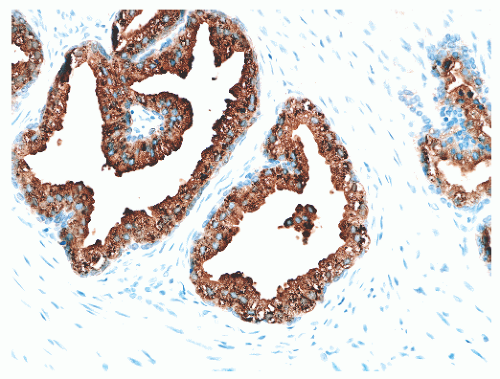

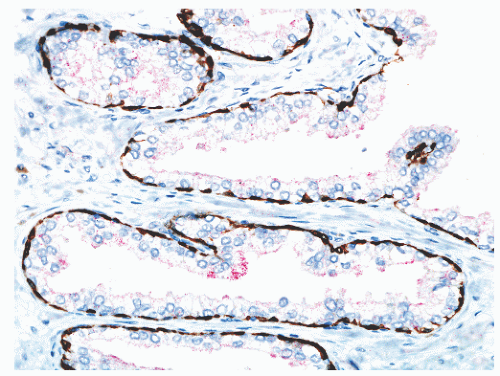

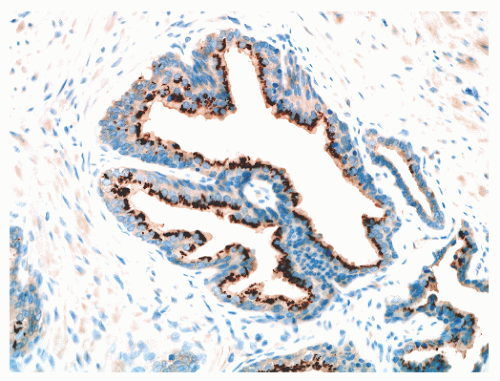

hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Fig. 8-11).25 The histochemical staining characteristics, including positivity for Fontana-Masson, PAS with diastase, Congo red, Luxol fast blue, and Oil-Red-O, and autofluorescence of the pigment are consistent with lipofuscin. This lipofuscin pigment can also be found in the cytoplasm of seminal vesicle and ejaculatory duct epithelium, where it is more abundant, coarser, and more refractile. The nuclei of normal prostatic secretory epithelial cells are small and round with fine, evenly dispersed chromatin. Nucleoli usually are not evident or are pinpoint in size. Nuclei in the central zone usually are larger than those in the peripheral zone and also appear crowded. This results in a pseudostratified nuclear appearance in the central zone and along with the aforementioned denser cytoplasm may yield a false impression of PIN.23 Normal secretory cells are immunoreactive for pan-cytokeratins, cytokeratins 8 and 18, PSA (Fig. 8-12), prostate-specific acid phosphatase (PSAP) (Fig. 8-13), and the androgen receptor. Of diagnostic significance, immunostains for α-methylacyl-coenzyme A racemase (alpha methylacyl CoA racemase [AMACR]; also known as P504S), a marker for prostatic neoplasia, can be focally positive in secretory cells in normal glands, but this staining should be focal and noncircumferential within normal and benign glands (Fig. 8-14).26 Additional prostate markers that have been utilized in diagnostic immunohistochemistry to assess for prostate versus nonprostate carcinoma include prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), prostein (P501S) (Fig. 8-15), proPSA, and NKX3.1. In normal prostatic tissues PSMA is weakly expressed in benign luminal cells.27,28 P501S is strongly expressed in benign luminal cells, with prominent dot-like Golgi complex staining29,30 (Fig. 8-15). Two different proPSA molecular forms differ in expression in benign glands, with strong or moderate/diffuse [−5/−7]proPSA expression and negative or weak [−2] proPSA expression.31 NKX3.1 immunostains show intense labeling of most secretory luminal cell nuclei, with weak staining of basal cell nuclei.32

|

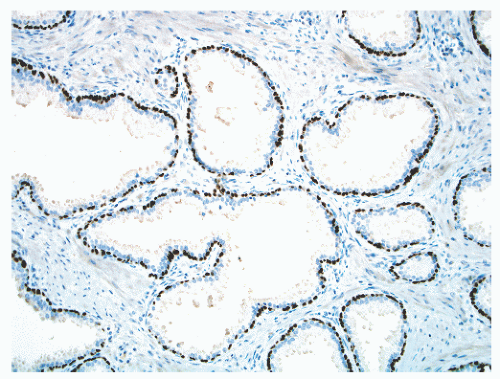

from luminal secretory cells, and can be of diagnostic utility. The most commonly employed basal cell-specific antibodies are those that react with p63 and high-molecular-weight cytokeratins, especially 1, 5, 10, and 14 that are detected by mouse monoclonal antibody 34βE12 (also known as CK903).26 A cocktail consisting of 34βE12 and p63 antibodies slightly improves the detection of basal cells (Fig. 8-12).34 Immunostaining of basal cells can also be achieved using antibodies directed against cytokeratins 5/6.26 It should be noted that discontinuity or even focal lack of basal cell staining may be seen in a minority of entirely normal glands.35 The precise function of basal cells is unsettled, but they represent the proliferative component of prostatic epithelium. Stem cells may reside within the basal cell population.

FIGURE 8-14 ▪ Focal, noncircumferential AMACR immunoreactivity in benign prostatic epithelium. Red, AMACR signal; brown, 34βE12/p63 cocktail antibody binding to basal cells. |

interdigitating nature of these cells, which exhibit slender, cytoplasmic dendritic process that may be up to 200 µm long. Neurosecretory granules of varying sizes are found in these cells by electron microscopy. The functional significance of neuroendocrine cells in the normal prostate is not clear, but it seems likely that the neuroendocrine products of these cells influence neighboring cells through the elaborate dendritic processes via a paracrine effect. Autocrine and endocrine influences may also be in operation.

FIGURE 8-15 ▪ Prostein (P501S) immunoreactivity in normal prostatic epithelium. Note granular perinuclear cytoplasmic pattern. |

FIGURE 8-17 ▪ Continuous basal cell layer in normal prostatic epithelium, as highlighted by a p63 immunohistochemical stain. |

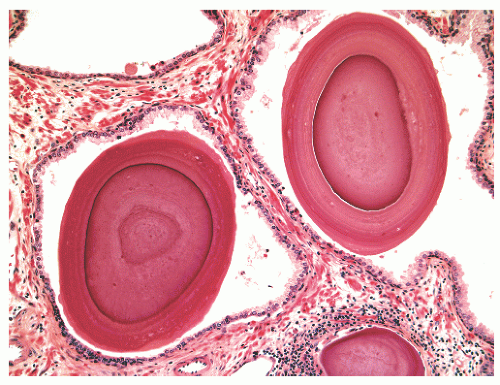

out malignancy. Corpora amylacea have been reported in 13% of carcinomas,45 and calculi are found associated with 6% of prostate cancers.46

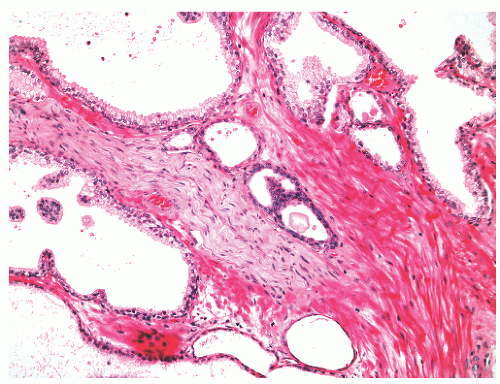

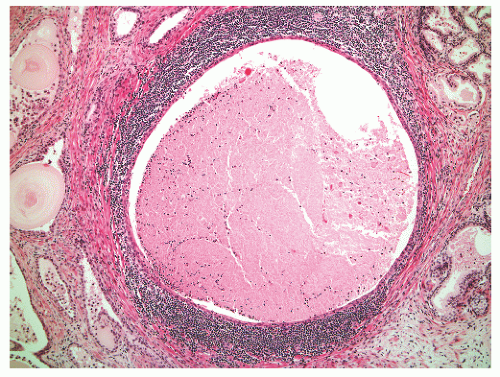

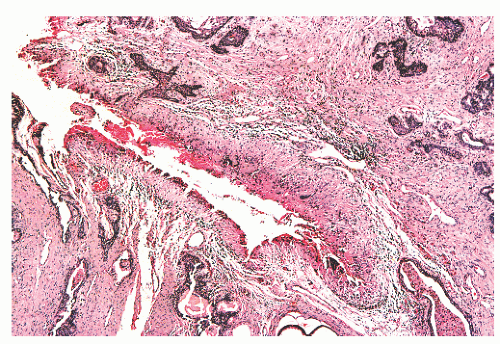

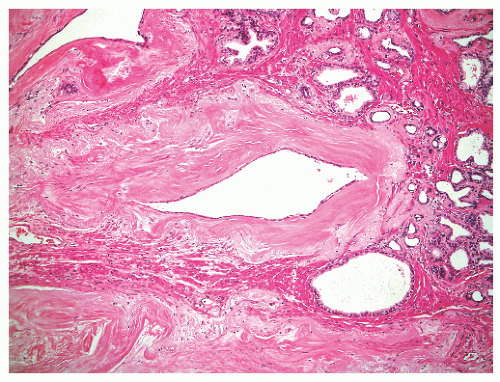

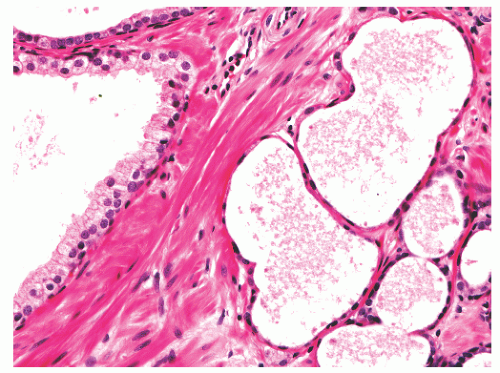

and extraprostatic tissue, but such vessels clearly can extend into the substance of the prostate and therefore are unreliable as a capsular marker. Anteriorly and anterolaterally, the band blends with the pelvic fascia. Apically, the band is no longer present, and instead there is a jumble of smooth muscle, skeletal muscle, and fibroelastic fibers. Here, it is important to know that the urethral striated sphincter (rhabdosphincter) is in direct continuity with the prostate, and indeed skeletal muscle fibers can normally be found, at an anterior and apical location, within the substance of the gland itself (Fig. 8-24).55 At the bladder neck, a capsular separation of bladder and prostate also does not exist; rather, there is a fusion of smooth muscle bundles (Fig. 8-25).

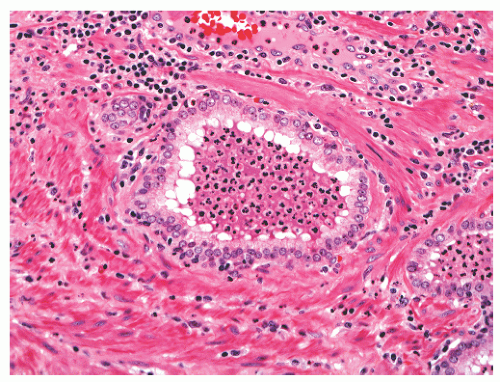

band, carcinoma invading around these structures should not necessarily be equated with extraprostatic extension of malignancy. Another diagnostic pitfall is the relationship of normal and benign prostatic glands to intraprostatic nerves. Benign prostatic glands can abut nerves61, 62, 63 (Fig. 8-27) and can even be found within nerves.63,64 Such glands should not be considered automatically malignant, and a constellation of histomorphologic traits should be used in diagnosis, not solely the physical proximity of prostatic glands and nerves.

foamy cytoplasm, and possess small, bland, basally situated nuclei. An acinar basal cell layer often is not apparent on H&E-stained sections. Immunohistochemical studies have produced mixed findings. In particular, studies have found luminal cells in the acini to be PSA positive67,70 or PSA negative68 and PSAP positive70 or PSAP negative.68 Also unsettled is whether the basal epithelial cells express high-molecularweight cytokeratins recognized by antibody 34βE12. The acini can be negative with 34βE12 immunolabeling.68 In most cases the basal cells are highlighted by antibodies to smooth muscle actin (SMA), which can be useful in the differential diagnosis with prostatic adenocarcinoma, although Cowper glands can usually be recognized by examination of H&E-stained slides without use of immunostains.

seminal vesicle, root of the penis, subvesical space, retrovesical space, pericolic fat, anal submucosa, perirectal fat, urachal remnant, and spleen.91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103 The most frequently cited type of prostatic ectopia is in the prostatic urethra in the form of prostatic urethral polyps. However, because prostatic epithelium normally can line the urethra in the verumontanum region, one could argue that these polyps do not represent ectopia.

|

present with pelvic pain localized to the prostate, perineum, or urethra, and a variable degree of voiding abnormalities such as urinary frequency, and sexual dysfunction.118 The etiology is unknown and optimal treatment has not been established.118 Acute bacterial prostatitis (category I) (usually due to Escherichia coli), is rare, being diagnosed in 0.02% of all prostatitis patients and chronic bacterial prostatitis affects 5% to 10% of patients with chronic prostatitits.119 Acute bacterial prostatitis is usually readily diagnosed clinically by the sudden onset of urogenital and often systemic symptoms, such as fever, chills, irritative voiding symptoms, and pain in the lower back, rectum, and perineum, along with bacteriuria.120 Treatment is with systemic antibiotic therapy.120 Patients with chronic bacterial prostatitis (category II), in contrast, experience prolonged or recurrent symptoms and relapsing bacteriuria. Treatment is more difficult and requires selection of an antibiotic with properties that allow for penetration into the prostate.120 Prostate biopsy is contraindicated in patients with acute bacterial prostatitis due to the risk of septicemia and prostate biopsy for patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome is currently a research tool only.121 Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis (category IV) is an incidental finding of unknown clinical significance, except that such inflammation can be associated with an elevated serum PSA.121

Table 8-3 ▪ NIH CLASSIFICATION OF PROSTATITIS SYNDROMES | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

histochemical stains. They increase in number with age130 but are not associated with any specific disease process.130,131 Eosinophils can nonspecifically accompany other inflammatory cells in histologic prostatitis (Fig. 8-33). The designation of eosinophilic (allergic) prostatitis should be reserved for those rare patients with a hypersensitivity disorder (such as asthma), peripheral eosinophilia, and large numbers of eosinophils admixed with granulomas.132, 133, 134, 135, 136 Macrophages can be found in dilated glands surrounding ruptured ducts and acini and in granulomatous prostatitis.

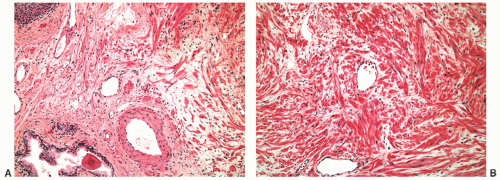

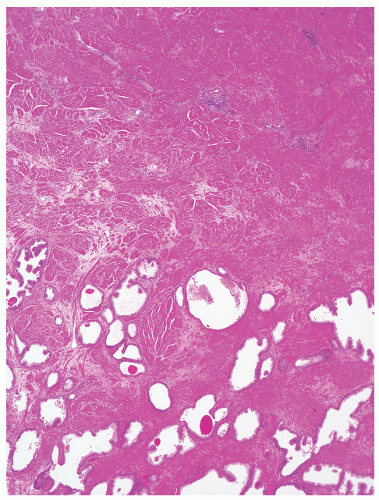

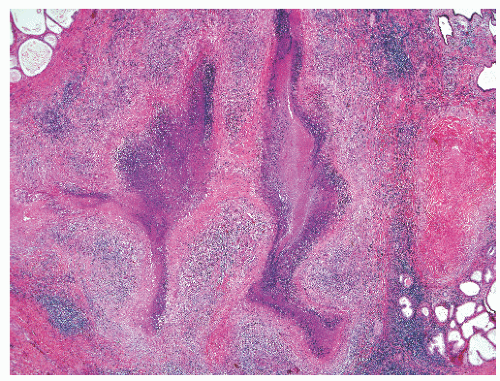

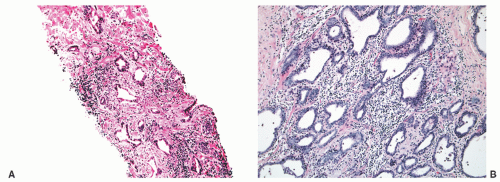

FIGURE 8-30 ▪ Chronic inflammation associated with atrophy in needle biopsy tissue (A) and in the whole gland (B). |

Table 8-4 ▪ GRANULOMATOUS PROSTATITIS: CLASSIFICATION | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

be pathogenetic components.144,151 The serum PSA is often significantly elevated, with a mean of around 13 ng/mL (range 0.4 to 114 ng/mL).148,152

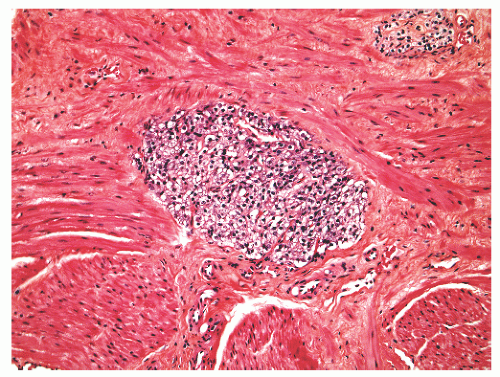

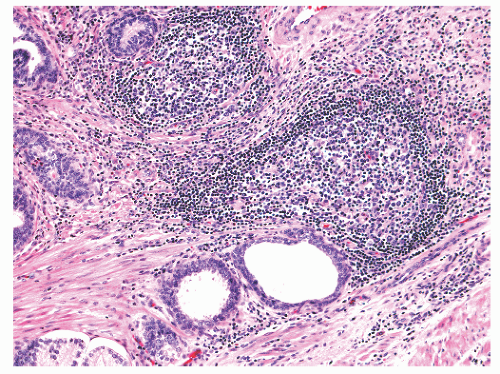

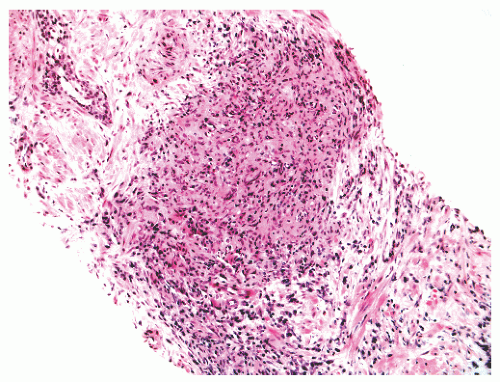

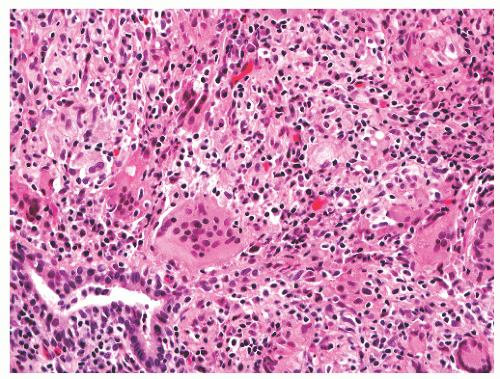

FIGURE 8-35 ▪ Nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis with a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells. |

immunoreactions for pan-cytokeratin, PSA, and PSAP, with immunopositivity for CD68 and lysozyme in the epithelioid cells are useful in establishing a diagnosis of granulomatous prostatitis in this context.147,148,158

performed. PCR specific for cryptococcal 18S rDNA from fixed prostate tissue was performed in one case.183

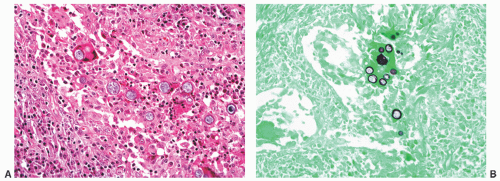

FIGURE 8-39 ▪ Coccidioides immitis granulomatous prostatitis (A) with spherules highlighted by Gomori methenamine-silver histochemical stain (B). |

contain brown pigment related to cautery-induced tissue carbonization.191 Older granulomas exhibit both central and peripheral hyalinization.

|

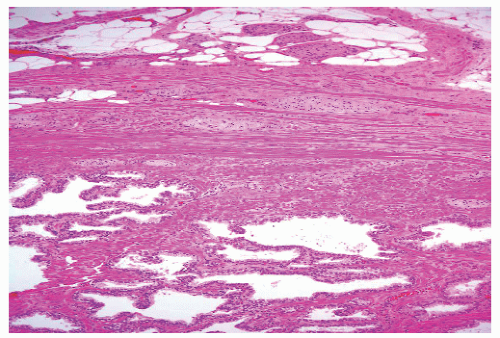

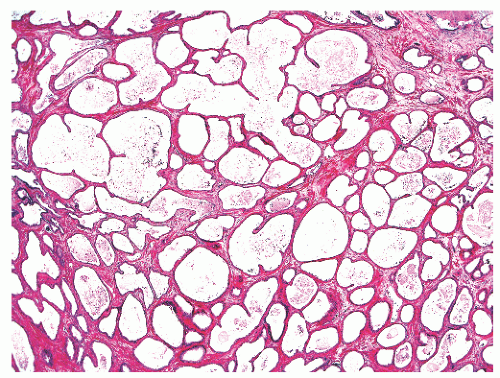

FIGURE 8-41 ▪ Simple atrophy, with a lobular configuration. Compare scant cytoplasm in atrophy versus adjacent benign nonatrophic glands where the luminal cells have a moderate amount of cytoplasm. |

FIGURE 8-47 ▪ Atrophy with chain-like appearance and nuclear atypia with nuclear enlargement and nucleoli. |

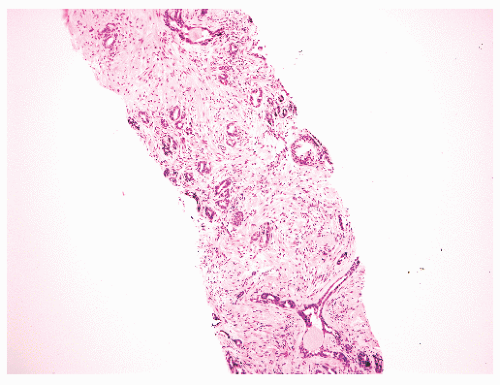

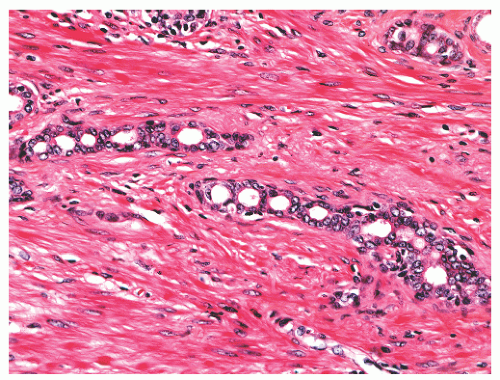

luminal surfaces and papillary projections. A stellate shape is assumed by some glands (Fig. 8-54

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree