Chapter 20 Minor Papilla Cannulation and Sphincterotomy

Pancreas divisum (literally “divided pancreas”) is a congenital anatomic variant in which the dorsal and ventral pancreatic ducts completely or partially fail to fuse and drain separately into the duodenum. Thus in most patients the vast majority of the pancreatic ductal system drains via the dorsal duct through the minor papilla. This is the most common pancreatic anomaly, occurring in approximately 10% of the general population, though rates vary worldwide from 2.7% to 22%.1,2 The frequency also varies greatly in different endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) series; a systematic review of endoscopic detection of pancreas divisum found a pooled rate of 2.9%, ranging from 1.5% in Asia to 5.8% in the United States and 6.0% in Europe.3

Although most patients with pancreas divisum do not suffer pancreatic symptoms throughout their lifetime, about 5% have recurrent mild to severe pancreatic pain, acute pancreatitis, or chronic obstructive pancreatitis. These symptoms or diseases very likely occur because the minor papilla orifice is so small that intrapancreatic dorsal duct pressure is excessively high during active secretion, resulting in inadequate duct drainage and distension.4 Persistent or recurrent high intraluminal dorsal duct pressure can cause recurrent bouts of acute pancreatitis and with time the gland undergoes chronic obstructive changes. Therefore pancreas divisum can be considered a predisposing factor for recurrent and chronic pancreatitis.5

Video for this chapter can be found online at www.expertconsult.com.

Patients with acute recurrent pancreatitis seem to have a significantly better response to MiES than those with pancreatic pain only and those with chronic pancreatitis.3 However, since some patients with acute recurrent pancreatitis continue to have attacks after effective dorsal ductal drainage,6 other nonductal abnormalities such as genetic mutations, alcohol, and autoimmune pancreatitis7 may play a pathogenic role. As many as 10% to 20% of patients with pancreas divisum and pancreatitis carry at least one allele of the cystic fibrosis gene product8 or a higher frequency of SPINK1 gene mutation than healthy controls,9 suggesting a multifactorial origin of pancreatitis in these cases.

Endoscopic identification, cannulation, and MiES are still challenging and the decision to perform ERCP in patients with pancreas divisum should not be taken lightly in view of the potentially high rate of adverse events. Although the minor papilla cannulation can provide the diagnosis of pancreas divisum, noninvasive imaging techniques such as secretin-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (S-MRCP), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), or thin-slice coronal computed tomography (CT) are preferable. S-MRCP is the preferred technique, with reported sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive and negative predictive values of 73.3%, 96.8%, 82.4%, and 94.8%, respectively.10 Secretin is essential for diagnosing pancreas divisum because MRCP without hormone stimulation is nondiagnostic in a substantial proportion of patients. Miss rates of pancreas divisum by MRCP may also be due to suboptimal techniques and reader inexperience.11

Indications for Minor Papilla Cannulation and Sphincterotomy

Box 20.1 lists the indications for minor papilla cannulation and sphincterotomy. The most frequent are recurrent pancreatic-type pain with a nondilated pancreatic ductal system, acute recurrent pancreatitis with or without dorsal duct dilation, and obstructive pancreatic-type pain or recurrent pancreatitis in patients with chronic changes of the pancreatic ductal system. In some patients without pancreas divisum, access to the pancreatic duct through the minor papilla and MiES can be useful.13

Box 20.1

Indications for Minor Papilla Cannulation and Sphincterotomy

Pancreas divisum and acute recurrent pancreatitis

Pancreas divisum and acute recurrent pancreatitis

Obstructive chronic pancreatitis (stone removal and/or stricture dilation)

Obstructive chronic pancreatitis (stone removal and/or stricture dilation)

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the dorsal duct (facilitation of transpapillary mucus drainage)

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the dorsal duct (facilitation of transpapillary mucus drainage)

Failed cannulation of the major papilla (guidewire rendezvous from minor papilla to major papilla)

Failed cannulation of the major papilla (guidewire rendezvous from minor papilla to major papilla)

Treatment of obstruction in the setting of pancreatic pseudodivisum or acquired dorsal duct syndrome

Treatment of obstruction in the setting of pancreatic pseudodivisum or acquired dorsal duct syndrome

Treatment of pancreatic disorders through the minor papilla in nondivisum patients in whom major papilla cannulation fails

Treatment of pancreatic disorders through the minor papilla in nondivisum patients in whom major papilla cannulation fails

Sedation, Supplemental Drugs, and ERCP Accessories

Sedation

Endoscopic cannulation and sphincterotomy of the minor papilla is generally a lengthy procedure, requiring appropriate sedation and analgesia. Deep sedation with propofol is therefore preferred, though moderate sedation can be achieved with repeated doses of benzodiazepines (midazolam) and opioids (meperidine, fentanyl) (see Chapter 5).

Supplemental Drugs

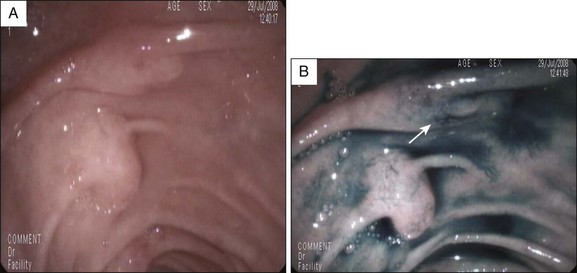

Although newer-generation, high-definition video endoscopes make it easier to identify the minor papilla and its orifice, in approximately one third of cases the orifice is not initially visible. In these cases dyes such as methylene blue or indigo carmine, and/or secretin, can be used to identify the papilla and its orifice. Secretin is expensive, so we usually use a dye spraying before secretin administration, although in many centers secretin is widely used initially to identify the papillary orifice, followed by dye spray when identification is unsuccessful. Methylene blue (vital dye) diluted with saline solution (1 : 10) or, preferably, indigo carmine 0.4% undiluted can be sprayed over the area suspected to contain the minor papilla in order to identify the papillary orifice or the papilla itself, respectively (Fig. 20.1). Once dye solution has been sprayed, the orifice may appear as a whitish spot emerging on a bluish mucosa, or is evidenced by clear juice washing away from the background blue dye.12,14 In patients with known incomplete pancreas divisum, methylene blue can be diluted 1 : 10 with contrast medium and injected into the pancreatic ductal system through the major papilla; part of the dyed pancreatic juice flows out through the dorsal duct and minor papilla. With this method it is best to avoid opacifying the entire pancreatic ductal system so as to limit intraductal pressure during contrast-dye injection and thus reduce the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP).

Secretin is a 27 amino acid polypeptide that strongly stimulates secretion of water and bicarbonate from pancreatic ductal cells; the enhanced secretion of pancreatic juice may render the minor papilla orifice visible. Intravenous secretin stimulates pancreatic juice flow between 1 and 3 minutes after injection with transient ductal dilation lasting about 15 minutes. However, when the pancreatic ducts are dilated or obstructed, as in severe chronic pancreatitis or dorsal duct stricture, the pancreatic juice flow after secretin may be insufficient to identify the minor papilla orifice. Two synthetic porcine and one synthetic nonporcine secretins are available for widespread clinical application in the U.S. and Europe, respectively. All secretin formulations significantly improve minor papilla cannulation rates and shorten cannulation time.15,16

Intraduodenal hydrochloric acid (HCl) infusion reportedly improves the minor papilla cannulation rate in patients with pancreas divisum during difficult cannulation.17 Intraduodenal HCl physiologically induces secretin release18 and is less costly than secretin. However, the preliminary data need to be confirmed in more patients.

ERCP Accessories

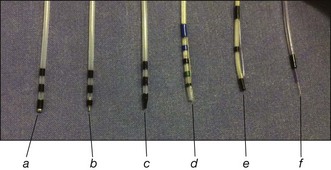

In general, cannulation and papillotomy of the minor papilla require much the same accessories as for the major papilla: a sphincterotome or an ERCP catheter and a soft-tip guidewire (Fig. 20.2). If the papillary orifice is very small, a needle-tip catheter (ERCP-1-CRAMER, Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, N.C.) can be useful. Sometimes a stenotic orifice requires dilation, which can be done with a tapered 3 to 5 Fr dilator (Contour catheter, Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass.).

Catheters: tapered tip 3 to 5 Fr catheters, some with metal tips

Catheters: tapered tip 3 to 5 Fr catheters, some with metal tips

Guidewires: partially or totally hydrophilic guidewire 0.018 to 0.035 in with straight and angled tips

Guidewires: partially or totally hydrophilic guidewire 0.018 to 0.035 in with straight and angled tips

Sphincterotomes: pull-type short-tip sphincterotome (4 to 5 Fr diameter) with a 20- to 25-mm cutting wire

Sphincterotomes: pull-type short-tip sphincterotome (4 to 5 Fr diameter) with a 20- to 25-mm cutting wire

Dilators: tapered 4 to 7 Fr dilators

Dilators: tapered 4 to 7 Fr dilators

Needle knife: 4-mm cutting wire with or without a channel for passing a guidewire or for contrast injection

Needle knife: 4-mm cutting wire with or without a channel for passing a guidewire or for contrast injection

Pancreatic stents: (a) “prophylactic”: 3 to 5 Fr stents, 2 to 8 cm long, flanged or unflanged with or without a duodenal pigtail; (b) “therapeutic”: 7 to 10 Fr, 3 to 7 cm long, flanged

Pancreatic stents: (a) “prophylactic”: 3 to 5 Fr stents, 2 to 8 cm long, flanged or unflanged with or without a duodenal pigtail; (b) “therapeutic”: 7 to 10 Fr, 3 to 7 cm long, flanged

Cautery unit: we use an ERBE generator model ICC 200 (ERBE Elektromedizin, Tubingen, Germany) usually set with effect 3, 120 W and “ENDOCUT” mode

Cautery unit: we use an ERBE generator model ICC 200 (ERBE Elektromedizin, Tubingen, Germany) usually set with effect 3, 120 W and “ENDOCUT” mode

Minor Papilla Cannulation (Video 20.1)

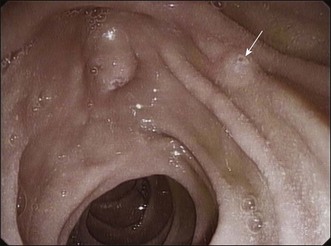

The first step of the procedure is to locate the minor papilla. It is usually in the right upper quadrant of the visual field, when facing the major papilla, 2 to 3 cm cephalic and anterior to the major papilla, but it may be as close as 1 cm from the major papilla, at the rim of its longitudinal fold (Fig. 20.3). The minor papilla can be recognized by carefully withdrawing the endoscope from the position of the major papilla. The long endoscope position makes for easier identification because of the better endoscopic and fluoroscopic views. The minor papilla can be very small and difficult to locate or quite prominent and, rarely, located within a diverticulum. When recognition is problematic, dyeing techniques or secretin injection can be helpful (Fig. 20.4). Gentle probing of the duodenal folds may be necessary to identify the minor papilla mound and to make it more prominent, although care must be taken to avoid excessive manipulation-related edema that may make it more difficult to identify the papilla.

The endoscopic appearance of the minor papilla can predict pancreas divisum and underlying pancreatographic findings.19,20 Bulging of the minor papilla mound and patency of its orifice may differ in patients with normal and abnormal ductography. About 70% of patients with pancreatic dorsal duct abnormalities have substantial bulging and a visible orifice, while most cases with a normal pancreatogram have no bulging and/or no visible orifice.21

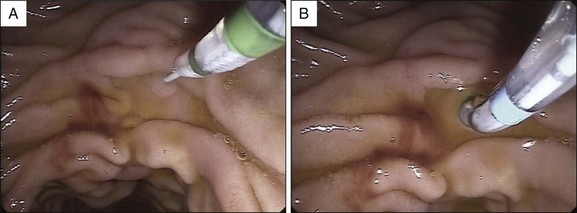

When minor papilla sphincterotomy is planned, it is preferable to begin cannulation using a pull-type sphincterotome preloaded with a guidewire, which is then used to enter the papillary orifice (Fig. 20.5). The sphincterotome also has an advantage when the en face orientation to the minor papilla cannot be achieved for initial cannulation: The sphincterotome can “bow” into the correct axis, facilitating cannulation. Once deep cannulation is achieved with the guidewire, if a long position has been maintained it is advisable to withdraw the endoscope into the short position along the lesser curvature of the stomach; this puts it into a more stable position in front of the papilla (Fig. 20.6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree