Omental involvement

97 %

Ascites

49 %

Serosal implants

19 %

Mesenteric involvements

16 %

Peritoneal implants

54 %

Interruption of the anterior peritoneal line

16 %

Liver metastasis

38 %

Lymphadenopathies

24 %

Gallbladder wall thickening

32 %

2.1 Ascites

Ultrasonography is a highly sensitive test in detecting ascites of small volume; (Branney and Wolfe 1995) for example, 5–10 ml ascites are clearly detectable. However, ascites is common in many benign conditions such as liver cirrhosis, portal hypertension, nephrotic syndrome, cardiac insufficiency, etc. (Runyon et al. 1988). Even if ultrasonography is often unable to distinguish between benign and malignant ascites, its presence in patients with known neoplasia is highly suggestive for neoplastic involvement of the peritoneum, and its presence in the lesser omentum (in absence of pancreatitis) is also highly suggestive for malignancy (Dodds et al. 1985). Some ultrasonographic characteristics may be helpful to differentiate benign from malignant ascites.

Frequently, in malignant ascites the fluid is echogenic (due to the presence of blood and/or neoplastic cells) (Fig. 1), septa are often present (Fig. 2), bowel loops are fixed and smashed for mesenteric involvement (Fig. 3), serosal and parietal peritoneal implants are often visible.

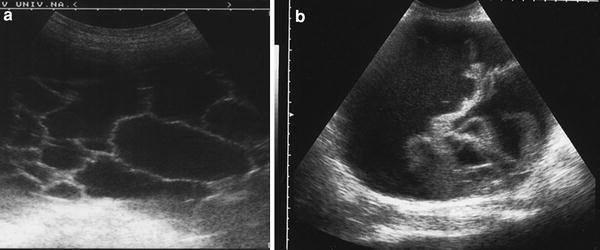

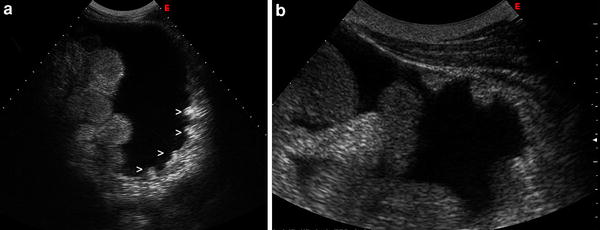

Fig. 1

Echogenic malignant ascites in a case of ovarian cancer: the fluid is echogenic with fine corpuscolated echoes and declivous sediment

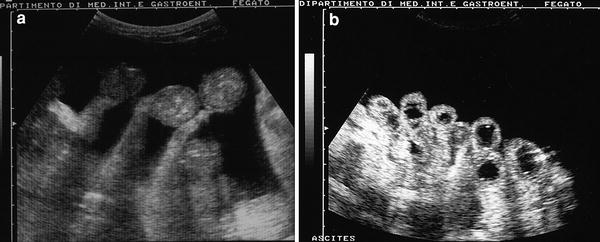

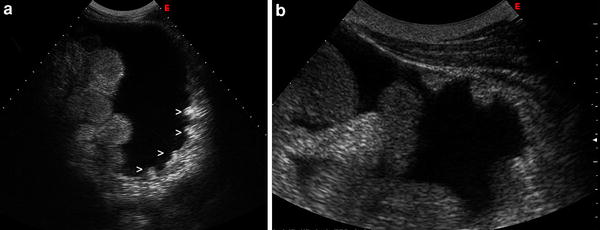

Fig. 2

a Ascites with fine hyperechogenic septa are clearly visible in malignant ascites due to pancreatic cancer. b More evident thickened hyperechogenic septa in malignant ascites due to gastric cancer

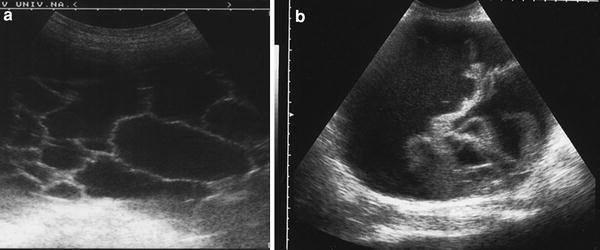

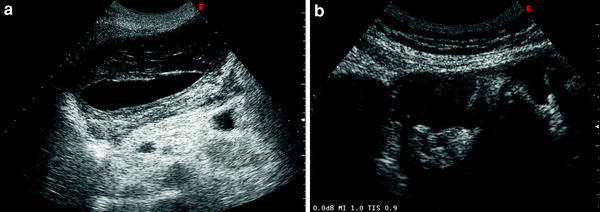

Fig. 3

a A case of benign ascites: note the bowel loops free in the anechoic fluid. b Contrary to what is seen in a, the intestinal loops are fixed and smashed in malignant ascites

Indeed, abundant ascites facilitates visualization of small nodules infiltrating parietal peritoneum, since it acts as a means of contrast (Fig. 4; Goerg and Schwerk 1991).

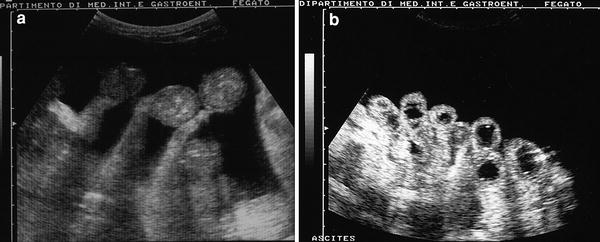

Fig. 4

a Very small nodules (>) are clearly visible on the posterior abdominal wall in a case of peritoneal involvement (colon cancer). b Small solid nodules (arrows) adhering to the anterior abdominal wall in a patient with ovarian cancer

Table 2 summarizes differential ultrasonographic characteristics between benign and malignant ascites; however, significant ascites is present in about 50 % of patients with peritoneal metastasis (Rioux and Michaud 1995).

Table 2

Ultrasonographic differential diagnosis between benign and malignant ascites

Ultrasonographic findings | Benign ascites | Malignant ascites |

|---|---|---|

Echogenic ascites | ± | + + + |

Septa | Absent | Present |

Peritoneal line | Regular | Irregular, interruption, evidence of nodules |

Omentum | Thin | “Omental cake” |

Mesentery | Free | Fixed |

Intestinal loops | Free | Fixed-smashed |

Liver metastasis | Absent | Present |

Lymphadenopathies | Absent | Present |

Other US signs | Liver cirrhosis Pancreatitis Cardiac failure | Absent |

Diagnosis of peritoneal metastatic involvement is often based on fluid analysis and ultrasound-guided aspiration of ascites is frequently used in patients with small amounts of liquid (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

Ultrasound guided percutaneous fine needle aspiration of ascitic fluid. Note the tip of the needle clearly visible in the fluid

2.2 Omental Involvement

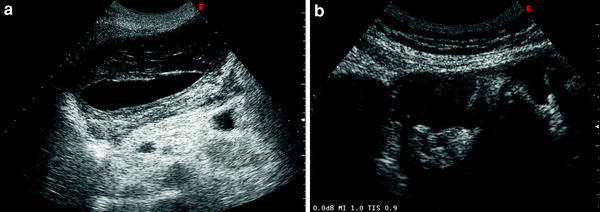

Stein (1977) clearly described the omental band as a new sign of peritoneal metastasis. Neoplastic infiltration of the great omentum is visualized by ultrasound as a uniformly thick, hyposonic band-shaped structure adjacent to the anterior and lateral walls of the abdomen, following the contour of the abdominal convexity and containing low-level non-structural internal echos (omental-cake) (Fig. 6). From this finding, a diffuse metastatic involvement of the omentum can probably be inferred with a high degree of reliability.

Fig. 6

(a, b) The “omental cake sign”: neoplastic infiltration of the great omentum is visualized by ultrasound as uniformly thick, hyposonic band-shaped structure adjacent to the anterior and lateral walls of the abdomen, following the contour of the abdominal convexity and containing low-level non-structural internal echoes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree